Paris is Burning is The History Lesson Americans Need

Cast, 1991: Back row: Angie Xtrava, Kim Pendavis, Pepper Labeija, Junior Labeija. Middle row: David Xtrava, Octavia St. Laurent, Dorian Corey, Willi Ninja. Front: Freddie Pendavis. Courtesy Janus Films.

It’s been 29 years since Paris Is Burning introduced New York City’s ballroom culture to the rest of the world, and it’s taken 29 years for the world to (sort of) catch up: Ryan Murphy’s groundbreaking FX series Pose, takes cues, and pays homage, to the documentary; RuPaul’s Drag Race contestants and fans alike are reminded, season after season, that reading is What? Fundamental!, and, of course, ball culture vernacular has been thoroughly introduced into our otherwise bland American lexicon. Though not without controversy, of course, Paris Is Burning has earned a legendary, and necessary, spot among queer film history, shining a bright spotlight on a subculture heavily made up of people of color and trans individuals. From Pepper Labeija’s stunning entrance to Octavia St. Laurent’s modeling ambitions to Dorian Corey’s seminal dissertation regarding shade and reading—reading came first, don’t forget—the documentary has successfully infused countless nuggets of priceless wisdom into pop culture. “You can like me or not,” says Jennie Livingston, the director of Paris is Burning. “There was no one else who was going to make that film. It’s good for people to learn from the ball world.” In honor of the film’s restoration, and its accompanying nationwide theatrical release, Interview sat down with Livingston to discuss the documentary’s lasting impact and complex legacy, her fondest memories while attending the balls, and why Paris is Burning is the history lesson Americans need most. Children, are you paying attention?

———

ERNEST MACIAS: What is the fondest memory you have of creating or watching the film? For me, it’s the image of those two little kids in the beginning.

JENNIE LIVINGSTON: When we met those guys, they were two boys hanging out outside of Sally’s Hideaway, where Dorian performed. That was right across from the New York Times building on 43rd Street—I met them randomly. They were not in any house, as far as I knew. They were a little too young. When that one guy said, “It’s like when a group of people pray together.” That blew me away because that had been my thesis. It’s like a spiritual environment where queer people who are rejected create sustenance amongst themselves and create a community. Also, when the balls would start, they’d say, “Grand Merch. Midnight.” But the ball really didn’t start until three in the morning.

MACIAS: That late?

LIVINGSTON: Balls would go until 11 am, then you’d have the drag queens exiting with the church ladies in Harlem walking around, leaving or coming to church. I always felt that way—that it was a spiritually and socially sustaining environment. I remember one of my earliest shoots, going to Willi Ninja’s house, and him saying, “You know, I want to be a big star.” He really felt that. A lot of people want to be famous. Fame is very overvalued in our culture. He had great talent and he felt an entitlement, a beautiful entitlement, to take his talent around the world.

MACIAS: What inspired you to make the film?

LIVINGSTON: I think it was the magic of New York City’s urban space. I moved to New York in ‘85. I was trained as a photographer and studied at Yale as a photographer and a painter, and the models in that photo department were Cartier-Bresson, Brassai, Robert Frank, and Diane Arbus. I don’t know why they did it, but my parents let me take this summer class called “Sight and Sound” at NYU. I was walking around Washington Square Park, and there were these guys boogieing by a tree and calling out category names like “Saks Fifth Avenue mannequins” and “butch queens in drag.” I asked to take a picture and they said, “No, he’s dancing.” They told me he was voguing, and I had no idea what that was. “If you want to see voguing, you have to go to a ball,” they said. “If you want to see more voguing, you should meet Willi Ninja.” I had to do a documentary assignment for the summer class, so I took the little wind up Bolex camera and went to this mini-ball, which is now called the Kiki Ball, at the Gay Community Center on 13th Street. I was walking around thinking, “What gender are these people? What’s going on?” Venus Xtravaganza was there. It was the first time I ever saw her. I showed the footage in class and everyone liked it. The more I went to them, the more I was thinking that this wasn’t about still images of dancers or participants. This was a subculture. This was about class, race, and gender, and how we construct our identity in the U.S. in 1985.

Friends at a Brooklyn ball, 1986 © Jennie Livingston.

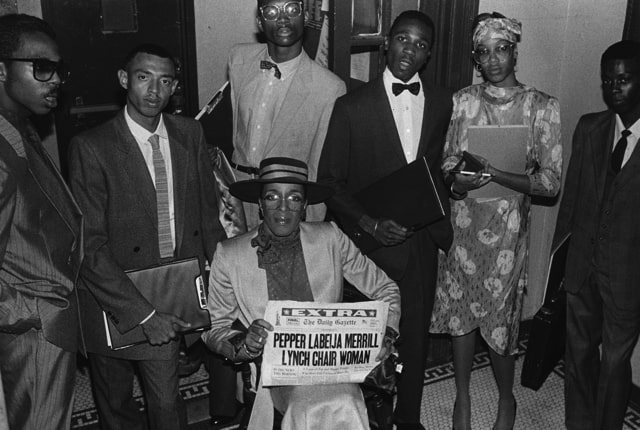

Pepper Labeija after walking Executive Realness (©) Jennie Livingston.

MACIAS: When you realized they had stories to tell, who did you approach first in the ballroom scene?

LIVINGSTON: I spent a lot of time with Willi from the House of Ninja. He also had a dance group called Breed of Motion. There was Archie Burnett, who’s still teaching Vogue worldwide. I got to know Venus, and I would go to her house in Jersey City and interview her. I went to Paris Dupree’s, and Junior Labeija’s house. You can get a good cassette recorder for not so much money, and it was a way of getting to know people and learning their stories. A lot of that audio did make its way into the film. My friend from school, Michael Moon, was interning at WNYC and he was making the VHS tapes of my trailer. One day he shows the film to his boss, she shows it to her boss, Madison Davis Lacy, who’s the head of the station, and he said, “Come back to me with a budget for a feature.” The budget was $250,000, and he gave me half of it. We were able to get a production van and a small crew–but a crew. We shot for five or six weeks, and that is most of the film. We went to balls. We went to the piers. We went to people’s homes. If I could have done anything, I would have shot vérité, but there was no way we could last.

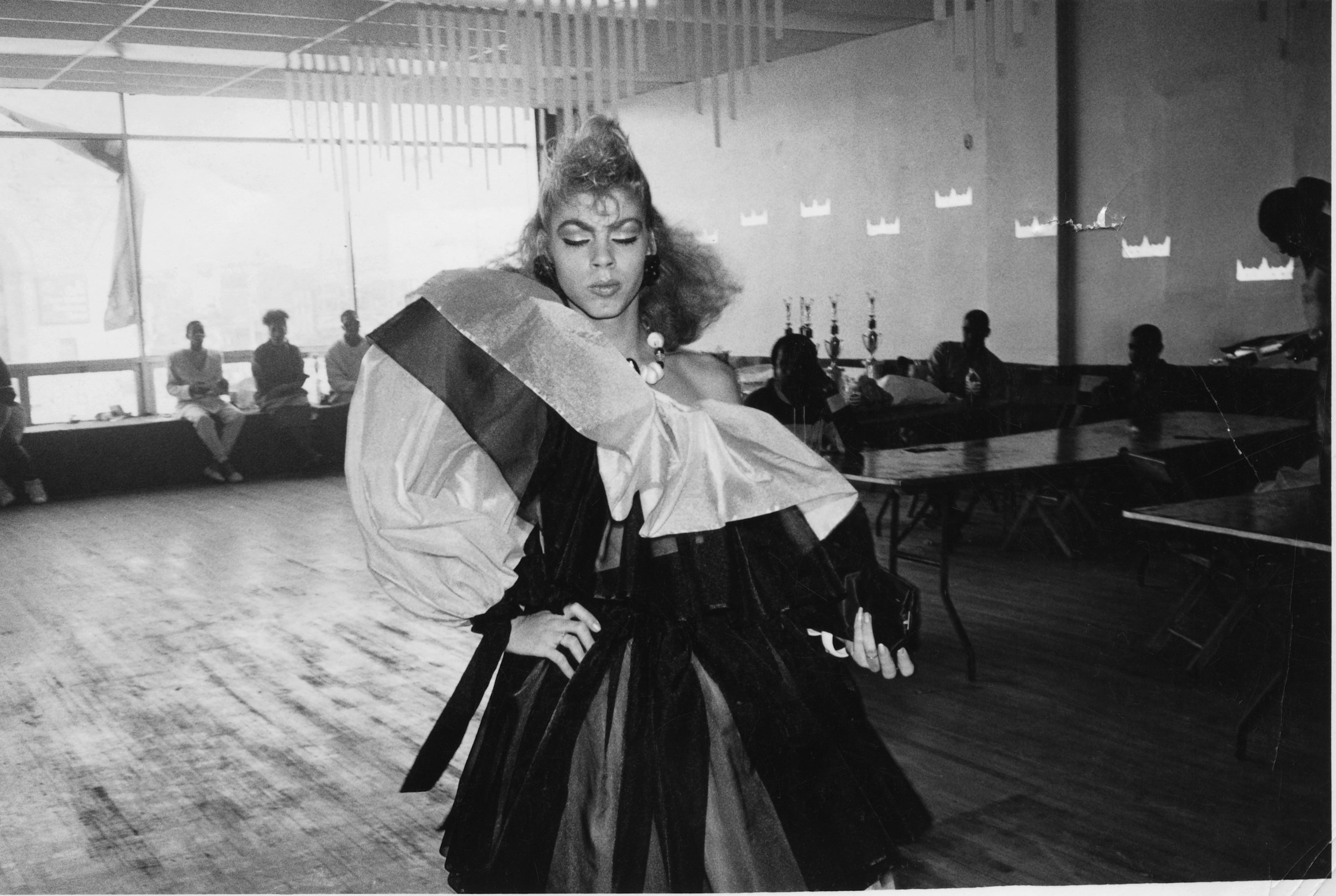

Venus Xtravaganza, Brooklyn ball, Eveningwear, 1986 © Jennie Livingston.

MACIAS: Was there any pushback from the community?

LIVINGSTON: They were totally welcoming. First of all, if you knew where to go, you literally had to get the flyer by hand. It was passed around hand-to-hand, or a friend had to tell you the address. There wasn’t an internet. You couldn’t find out about it casually. Plus, it was a show, people were there to perform. Now, in terms of having intimate conversations with people, that’s more like developing a relationship. There were a couple of people, who when we finally did get the money and we finally had our five weeks of shooting and we were going to do interviews, they didn’t want to be interviewed. There was one guy that we were following, a young guy who was in school and ROTC. He didn’t sign a release. He didn’t want to lose his career if he was going into the military. He’s in the credit sequence–there’s a guy dancing in a grass skirt with his face painted. You can’t recognize him, so we left it in.

MACIAS: What would you say was the purpose of the film when you made it?

LIVINGSTON: To give the people in the film an opportunity to say what they had to say as people and for their culture. What you see in the world, it passes. To have Dorian’s wisdom, Pepper’s wisdom; to have Willy’s moves, and to have the beauty and variety of what happens in a ballroom, to have that live in film. We create race. We create gender. We create class. We prevent many people from shining or flourishing, and allow many other people to shine or flourish based on very old histories and based on a set of assumptions–many of which are toxic. Now, if you like the film or if you don’t like the film, whatever it is, you can still meet those people because the film exists. There was no one else who was going to make that film. It’s good for people to learn from the ball world. You can like me or not like me, but the film—it’s American history that deserves to be seen by every kind of American.

Voguer, Brooklyn ball, 1986 © Jennie Livingston.

MACIAS: What purpose does the film serve today?

LIVINGSTON: Who could have imagined this man as president? Trump is deliberately and systematically–and in the way of what Nazis did– targeting trans people. He’s targeting queer people. He’s targeting immigrants and children of immigrants. He creates hate. So here’s a film that is about people creating not division, but unity. It’s about dignity. It’s about intelligence. It’s about expression. The film was made in the age of AIDS, when so many people were dying from so many communities. Reagan wouldn’t say the word. I was in ACT UP, and we were fighting to make people aware of a plague that was killing particular populations. Here we are, back in this situation, where we actually have a leader who’s using hate to divide Americans.

MACIAS: Now that the film has been restored and released in theaters, do you think that it will bring to light other issues, like it did back then? Or will it put on blast how little things have changed for trans women of color or queer people of color, specifically?

LIVINGSTON: I think it depends on what conversations people have. I’m a filmmaker, right? My intention was to tell a story so people can see the story, see the people, and have the conversation. I think there’s obviously been an evolution. Paris Is Burning was completed in 1991. It created space for other people to make other films and to have other conversations. There’s a trans movement. I think trans activists, trans communities, and allies to trans activists and trans communities have to have these conversations. The violence is intense. The number of people murdered goes on. Venus’s murder was not solved. Are the current murders being solved? I don’t think so. It was very complicated to figure out how to make the film, because if it’s too cheery, then it’s just fake. If it’s too much edginess and too much hardship, then it’s implying that the people don’t have self-determination, and it’s just pathetic. How do you balance those things? I’m proud that all of these years later, the film has meaning to new activist movements, to younger people. That was the point.

MACIAS: There’s an obvious generational gap, a sort of disconnect between now and the time of the film’s release. What can young queer people do to recognize that history?

LIVINGSTON: My take is: know your history. Read Randy Shiltz, And The Band Plays On. See the movies. Take a class. The issues of self-hate and self-love are the same whether you’re at risk for HIV or you’re not at risk for HIV. Talk to people who are older. Ask them to tell stories. Don’t be stuck in your generation. That’s one of the problems with queer culture—we don’t always know older people. Read history because you’ll begin to understand. Take somebody out for a drink and say, “What was it like when your roommate died? What was it like when your lover died? What was it like when you were afraid?” Because as horrible as that time was, there was so much unity. I was in a community where people were dying–I got tuberculosis from my roommates because they had HIV. If you’re a storyteller, if you’re a writer, tell those stories. I think that’s our sacred duty: to tell the stories of our community, or at the very least, know them more deeply.