Pablo Trapero’s Family Affair

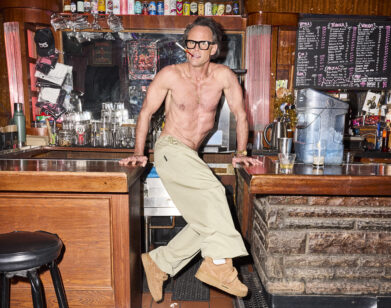

ABOVE: A STILL FROM PABLO TRAPERO’S THE CLAN. PHOTO COURTESY OF FOX INTERNATIONAL.

After taking its native Argentina by storm and becoming the nation’s highest grossing opening weekend box office to date, producer-director Pablo Trapero’s The Clan debuts in New York City and Los Angeles today, March 18. The noir film tells the chilling, true-life crime tale of Arquímedes Puccio (Guillermo Francella), a steely-eyed patriarch who, in the early ’80s, kidnapped, ransomed, and killed four of his community’s elite under his family’s roof. Within the Puccio family, blood equals loyalty, and Arquímedes’ clan remained complicit through silence. In his rugby star son, Alejandro (Peter Lanzani), Arquímedes even found an accomplice, although one who eventually led to the entire family’s demise.

When The Clan competed at the Venice Film Festival last year, it received the Silver Lion award, and earlier this year received honorable mentions at the Toronto International Film Festival. Though Trapero explores a sensitive, emotionally difficult, and truthful story, it is not the 44-year-old’s first time doing so. In Mundo Grúa (1999), he portrayed the life of a migrant contract worker; in the acclaimed El Bonaerense (2002), he focused on corruption found within the Buenos Aires police force. He’s dealt with taboo subject matter as well, including incest, in Géminis, which he produced in 2005.

Earlier this week, we spoke with Trapero about bringing this story to the screen, casting unlikely Argentinian stars, and finding his way inside audiences’ heads.

BENJAMIN LINDSAY: For me, and I’m sure for other American viewers, the Puccio family’s story and crimes are unfamiliar. Is it common knowledge in Argentina, or something that you dug up?

PABLO TRAPERO: It was famous for my generation and older, but when I decided to create a work based on the case in 2007, I realized [the story] wasn’t that vocalized. Of course, some people know the name and understand, more or less, what it was, but books or real investigations about Arquímedes [were] about the crime site. I wanted to do a movie based on the family day-to-day, the background of the daily life of this family.

We had to do our own research. That took awhile. We talked with Alejandro’s friends, who were the trainers of the club, who were the neighbors; the lawyers and the judges who had access to the files to the testimonies of the other Puccios; the relatives of the victims. We talked with a lot of people to recreate this identity. It was an amazing and somewhat painful process because we talked with people who had suffered and their lives changed, totally, because they crossed paths with these crazy people.

LINDSAY: Why was it important for you to draw these characters in their day-to-day?

TRAPERO: It’s so extreme, what they did. I think that’s why [the way to] approach the case was through them. Before the crime story, before the period in Argentina, and even before the whole family, it served as a portrait of a father and son’s relationship. It’s something that could make the film more universal. If you don’t know the Puccios, if you don’t know what Argentina was like back then, it’s about what we could all understand from this link, this relationship. It’s universal, but in this particular case, a bit crazy. I think that that makes the story wiser, more open to go deeper into the crime site and crime details.

LINDSAY: How did you go about casting for the film? With Guillermo Francella in particular, he’s incredible. Was he someone you wanted from the beginning?

TRAPERO: It was an additional challenge because Guillermo is a very, very, very popular and famous actor from comedy. But, as we can see, he’s a great actor. So I talked to him in the very early stages of the process. Even before I finished the final draft, I turned to him to find out if he was ready to do it, because some actors don’t want to have this kind of relationship with the audience. That was the main question: Are you ready to be a character that horrifies the audience? He immediately told me, “I’m totally ready.” A funny thing for him was that he lived in a place close to [the Puccios]. He knew the story very well. He was very close to some details of the story because he lived, like, 15 blocks away.

LINDSAY: Considering his roots in comedy, was that a concern of yours? For him to tackle a role with this kind of depth?

TRAPERO: I wanted to take advantage of his popularity in this sense. It was important to understand that in [Arquímedes’] daily life, people, I can’t say loved him, but respected him. It was somebody that people have some empathy with, some sense of closeness. The whole family was well-known there, mostly because the mother was a teacher at the school and the kid was not only a good [rugby] player, but a star. He played in the national rugby team. Peter [Lanzani] is also very famous in Argentina. He used to do these kind of teenager shows; he was very famous then, when he was 15.

I tried to share with the audience the same feeling that the people in general had back then. It was a challenge because we didn’t know how it could happen or how we could finish, but the film was great and a big success in Argentina and in every way, really doing well, not only with the general audiences, but different audiences—festival people, the critics. The people have the chance to really feel somewhat close to them when they are these monsters.

LINDSAY: There’s so many memorable sequences in this film, including several montages pairing Arquímedes and Alejandro’s day-to-day. Was this a tool to show the dualities of father and son, or was there another purpose?

TRAPERO: Yes, [but] it was also a way to put the audience in the victim’s point of view. For Alejandro and Arquímedes, they were not really scared or worried. They had lunch or breakfast in the morning and in the afternoon, they kidnapped somebody. It was exactly like that. It’s really scary, but it was the way it was. At the same time, the long sequences, long takes, mostly the kidnappings that take place, are always from the victim’s point of view. And the music can also sometimes help create this victim’s point of view. Another thing that helped us create that sense is the phone calls. We would have a big shot [with Arquímedes], but the voice on the other side of the phone is very clear, so we can really see what the relatives of the victim were living at that time, even when it’s just a voiceover on the telephone.

LINDSAY: Looking through some of your other films, I couldn’t help but notice that you are often exploring political and social narratives. The Clan itself is set to the backdrop of political turmoil after Argentina’s Dirty War. As a filmmaker, do you feel a responsibility to make films with a message?

TRAPERO: Yes. It’s hard to say that it creates a message because it depends on who is on the other side of the screen, but I try. I like to get something else when the film ends—the films I love are the films where everything starts when the film finishes, when you’re out of the screening room, when you’re left with the memories of the things you have seen. That’s what I try to do with movies. I think movies talk to us and help us to understand our own life.

THE CLAN OPENS IN NEW YORK CITY AND LOS ANGELES MARCH 18, 2016.