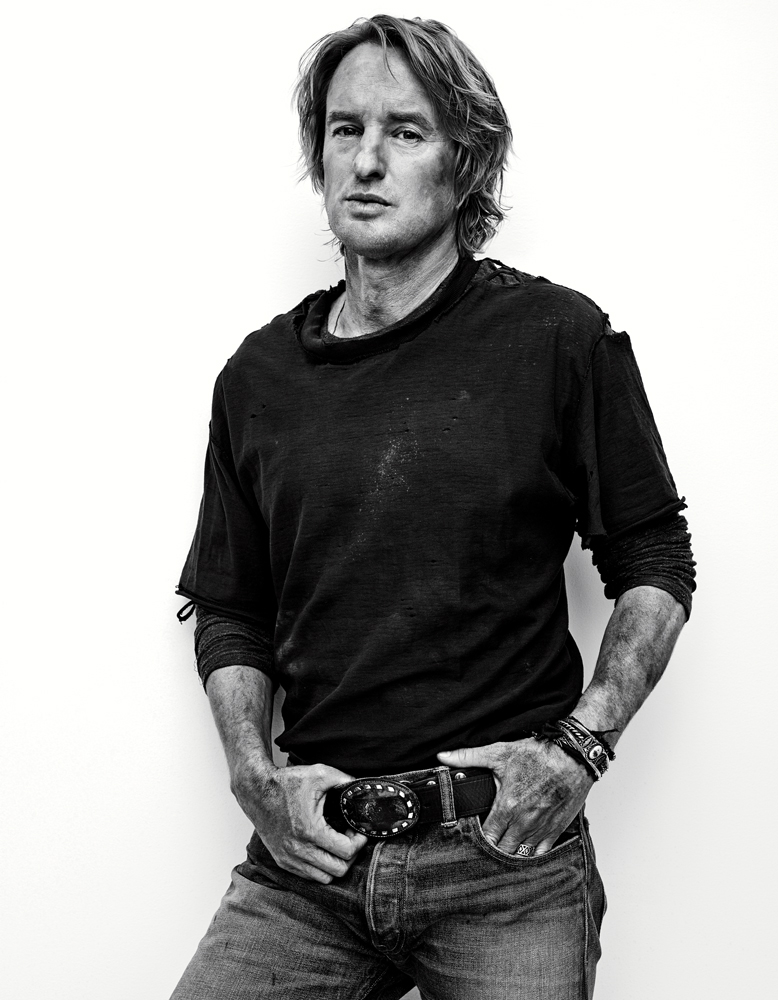

Owen Wilson

It’s not enough just to be real; you have to try to make it interesting or entertaining. owen wilson

How wonderfully weird is Owen Wilson? Weird enough that he can—as he did playing Eli Cash in The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), which he co-wrote with director Wes Anderson—say, apropos of nothing in particular, “I’m sorry, don’t listen to me. I’m on mescaline. I’ve been spaced out all day,” and make you think, “Ah, yeah, that’s it.” Really, even among oddball comic performers, whose whole thing is to entertain, to get weird, Wilson is unique. Whether he’s doing that kooky broken-nose woundedness thing in one of Anderson’s dollhouse dioramas or playing the shaggy golden retriever straight man to Vince Vaughn in Wedding Crashers (2005), Wilson’s wonderful weirdness is amazingly consistent. He is never you or me—he’s always Dupree. Not that he’s hemmed in by that screen persona. Wilson’s Wilsonness has proven to be amazingly elastic, pairing well with the Jackie Chans and Eddie Murphys of the buddy-comedy world and stretching its way from traditional fare, like Marley & Me (2008), all the way to Wilson’s most delirious collaborations with Ben Stiller, Starsky & Hutch (2004) and Zoolander (2001). Never for a second does Wilson lose his syrupy drawl or giddy, syncopated ebullience.

Wilson, now 47, was born and raised in Dallas. At the University of Texas at Austin, he roomed with Anderson, and together they wrote the screenplay for Anderson’s first feature, Bottle Rocket (1996). The actor’s and the director’s careers sort of mushroomed from there. But who is Owen Wilson? In life, he’s about as knowable as Coy Harlingen, the character he played in 2014’s Inherent Vice—which is to say hardly at all. But whatever we know or don’t, or think we can infer about Wilson’s extratextual life—and however much that is changed or informed by the song his ex-girlfriend Sheryl Crow reportedly wrote about him, or by news of his apparent suicide attempt in 2007—Wilson the performer seems immediately knowable. He’s an easy read onscreen. Even when he is a villain, as he is, perhaps unknowingly, in the Meet the Parents movies, he’s all earnest goofiness. There is never any sarcastic edge to Wilson’s characters. Often they are downright dreamers, lost little boys maybe, but eager, wide-eyed in their searches, whether for a father (as in Anderson’s The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou, 2004) or a life of meaning (The Darjeeling Limited, 2007). And, it should be said that Wilson does the very best “actor playing a Woody Allen surrogate in a Woody Allen movie” as the golly-gee dreamer Gil in the magically compelling Midnight in Paris (2011).

For sheer Wilsonness, though, it would be hard to top Hansel, the Razor-scooter-riding model and spider-monkey aficionado Wilson plays across from Stiller’s Derek Zoolander. Hansel is so cuddly a character that even the high guard of fashion, whom the movie is most directly lampooning, loves him to pieces. And, after Wilson and Stiller made a surprise appearance in the Valentino runway show in March, who doesn’t? As Wilson readied for the release of Zoolander 2 this month, he spoke with Valentino designers Pierpaolo Piccioli and Maria Grazia Chiuri about dropping into Paris Fashion Week for their show, living in Rome, and the art of cinema.

PIERPAOLO PICCIOLI: Hey, Owen. How are you?

OWEN WILSON: I’m good. Where are you guys?

PICCIOLI: We are in New York.

WILSON: Okay, I’m here in Malibu. I got back from Miami yesterday, so now I have a holiday.

PICCIOLI: This is a big position for us, the first time we are interviewers, but we promise not to ask you about sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. [Wilson laughs] Now, people are dying to know: What shampoo do you use on those golden locks?

WILSON: [laughs] Well, you have to mix it up. You can’t get too attached to any one shampoo. And conditioner, also.

PICCIOLI: A lot of conditioning.

WILSON: Yes, exactly. [laughs]

MARIA GRAZIA CHIURI: We first met in Paris, at our show. What was that like for you?

WILSON: I guess I was a little bit nervous, because there seemed to be so much secrecy with Ben [Stiller] wanting to make sure that it was a surprise when we walked out on the runway. I remember showing up at Place Vendôme and doing the fitting and seeing the pajamas that I was going to wear—which I like very much—and seeing Ben arrive kind of in disguise. And, of course, we didn’t know what the reception was going to be when we walked out on the runway, but it felt like we were in a rock band. People started cheering. It was a nice way to begin Zoolander 2, with that kind of reception.

CHIURI: A great moment.

PICCIOLI: It was a moment when everyone shared fame’s energy. It was a moment of freedom in fashion—you could watch and not take everything so seriously.

WILSON: Yes, it was fantastic, and it was nice that you guys have such a good sense of humor, because some people don’t have the ability to laugh at something. It’s not a very attractive quality. Anna Wintour was there, and we did the little thing with her before the show. And, of course, she has a reputation—she can be very intimidating—but that day she was just smiling and laughing. That was my first time meeting her, and she seemed like she was having a great time. Everybody was enjoying themselves.

PICCIOLI: Now, our first real question, maybe the most complex: Why did you become an actor?

WILSON: Well, I think it was something that I just sort of fell into by luck. My roommate in college in Austin, Texas, was Wes Anderson. Wes always wanted to be a director. I was an English major in college, and he got us to work on a screenplay together. And then, in working on the screenplay, he wanted my brother, Luke, and me to act in this thing. We did a short film that was kind of a first act of what became Bottle Rocket. It was something I didn’t know I would continue to do, because it’s a little bit out of your hands—it just depends on how people react to you or if people want to hire you. Maybe that’s why there’s an insecurity sometimes in acting, because it’s not like there’s a correlation between hard work and how people receive you. But after Bottle Rocket, I started getting acting work. People started offering me roles in movies. It wasn’t something that I thought about as a kid growing up in Texas. Actually, maybe I would have thought of it as a possibility, but it seemed so crazily far-fetched to think that you could work in movies that I really didn’t ever quite imagine it. It was just lucky.

PICCIOLI: Wes is, of course, part of your career. You co-wrote maybe one of the most iconic fashion movies, The Royal Tenenbaums.

WILSON: Oh, yes, we worked together writing a couple more movies together: Rushmore [1998] and Tenenbaums. We filmed Life Aquatic, actually, in Rome, at Cinecittà, where we filmed Zoolander 2. I lived in Rome for about five or six months during Life Aquatic, so it was nice to return to Rome. And the city hadn’t changed at all. I guess that’s the thing about Rome: It never changes. The apartment that I rented in Rome this time was so great. It was right next to the steps, the Capitoline that Michelangelo designed.

PICCIOLI: I remember you biking in Rome.

WILSON: I was in Rome this time for about three or four months, and I feel like, by the time I left, every single person in Rome had seen me at least 10 times riding my bicycle. When I first got there, it seemed like people were happy to see me and would say hello. And by the end, they were kind of bored of seeing me. And it was like, “Ugh, there he goes again.”

Hansel is certainly about comfort, while still sort of having a peacock principle of wanting to attract attention. owen wilson

CHIURI: Dark comedy is an important part of your career. Why do you choose these roles?

WILSON: Well, it isn’t so much that I choose the roles—I mean, I guess there’s a little bit of a selection process—but it’s more just what people offer you. So it’s a lot about the way they see you. The movies I’ve done with Wes have a much different quality than some of the more broad comedies. But what is interesting is how many sequels I’ve done. I’ve worked with Ben a million times now, and this is yet another sequel we’re doing. I guess we’re lucky to be in some movies that people wanted to see again.

PICCIOLI: We are always asked where our inspiration comes from when we design a collection. How do you, when building the characters you play, build the layers of the character?

WILSON: I try to find a way to make it comfortable or interesting or funny to me. I remember working with Jackie Chan on Shanghai Noon [2000], and when we were working on the script, I thought that my character thought about being an outlaw the way a kid today would think about being a rock star, as a way to impress girls. So it was just kind of a funny idea, but once we had that idea, it changed the character and made it something that was funnier to me to play. But maybe because I began as a writer, I have a good ear for dialogue, and maybe being an English major—and that I also read a lot as a kid—if I hear somebody say something that I think’s funny, or I find a situation or story, I’ll try to work that into the movie.

CHIURI: Is there a part of you in every character you’ve played?

WILSON: For sure, because it’s me playing the character, trying to find a way to make it believable and entertaining and interesting. I remember hearing a good story about Jack Nicholson working with Stanley Kubrick on The Shining [1980]. Nicholson was saying that, as an actor, you always want to try to make things real. And believable. When he was working with Kubrick, he finished a take and said, “I feel like that was real.” And Kubrick said, “Yes, it’s real, but it’s not interesting.” It’s not enough just to be real; you have to try to make it interesting or entertaining.

CHIURI: And you have a passion for art. Is that true?

WILSON: Yes. My mother’s a photographer, and she worked with Avedon for years on the American West project. So when Mr. Avedon would come to Texas to visit, they would go to Montana and Wyoming. My parents would take us to the museums a lot, the way parents do. But it was really through my friend Tony Shafrazi, who’s an art dealer and an artist himself—he helped to show Basquiat and Keith Haring, and has worked with the Francis Bacon estate—it was really through my friendship with Tony that I developed even more of an interest in art. And Peter Brant, who is a good friend. So knowing those guys. But yeah, my mother photographed Donald Judd in Marfa, Texas, right before he passed away. He was actually the first artist whose work I collected. I just loved the photographs that my mom had done of Donald Judd and the installations in Marfa.

PICCIOLI: Who are your favorite artists?

WILSON: I love Francis Bacon. I just saw a great Jackson Pollock exhibit at the Dallas Museum when I was home for Thanksgiving. The first thing I remember is Alexander Calder—our school took us on a field trip to go see the Calder mobiles, and that always stuck in my memory. In Rome, I loved seeing the Caravaggios. There are churches in Rome that have Caravaggios, and there’s one, not far from Piazza Navona, that has the best, I think: St. Matthew with the money. I love those. And also Richard Prince, Urs Fischer, Nate Lowman, Christopher Wool …

PICCIOLI: Do you see any similarity between fine art and cinema?

WILSON: I think of Terrence Malick’s movie Days of Heaven—one of Richard Gere’s first movies—you can push pause on almost any image in the movie and it looks like a painting. And it’s funny, I saw Ben Stiller’s movie Walter Mitty [2013] the other day; it’s very beautiful. You look at some of the movies John Ford did with John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart, and then look at Remington and Ansel Adams, and I think you see a connection, certainly in the imagery of the West.

PICCIOLI: Do you feel like you are an artist shaping a character? Or do you think it’s more about the director?

WILSON: Film is definitely a director’s medium. They’re responsible for the look and everything, and you’re a part of that process as an actor, and you try to contribute to the story. But I think it might sound a little pretentious for me to say I think of myself as an artist. I think of myself as a creative person.

PICCIOLI: What was the most important moment in your career? The one you remember most, the one you want to save.

WILSON: I think for Wes and me, the most important thing was James L. Brooks producing our first movie and giving us a chance to come to Hollywood, because without him, we might never have gotten the chance. I remember that like it was yesterday, and it was over 20 years ago: him coming to Dallas and meeting with us; doing a reading of the script for him, then going to dinner with him later. Just the excitement that we had that we were maybe going to be able to make a movie. And he then sort of became our mentor, brought us out to Los Angeles and worked on the script for a year with us. We learned so much working with him—just being able to spend time with him, the quality of his mind, the things he comes up with and says. I think Wes and I could go to dinner tonight and spend the whole dinner thinking and talking about things that Jim has said to us over the years. He’s just a very original person. So that was definitely the luckiest, most important thing that happened to me. Then I guess also meeting Ben Stiller. He cast me in the only thing I think I ever auditioned for and got: Cable Guy [1996]. And that led to us becoming friends. And I’ve worked with him more than anybody. I always think about Katharine Graham—she was the publisher of The Washington Post. In her autobiography she talks about the way her parents met. Her father was, I think, in New York just walking by on his way home and looked into a store and saw the lady that became his wife. It was just pure luck. And she said that it once again reminds her of the role that luck and chance play in our life. I really believe that, too.

CHIURI: And now we know that you love shopping. What about it do you like?

WILSON: Well, I like the Valentino store in Rome. [laughs] Because in Rome when I’d be riding my bike, that store is right next to the Spanish Steps, and it gets so crowded there, so I could sometimes duck into the Valentino store and go up to the top floor and have a little espresso and just relax and take it easy. And then I became sort of an aficionado on the Valentino pajamas, because I like those so much. I think somebody like Wes has a very good sense of style and is original. I think my sense of style got a little bit better after I was exposed to you guys at Valentino. Because I’m just in Hawaii and Malibu; it’s just kind of T-shirts and surfing-type stuff.

PICCIOLI: Fashion is fashion. Style is how you make fashion personal. It could also be about how to be ridiculously good looking.

WILSON: How to be really hot. [laughs] Hansel is certainly about comfort, while still sort of having a peacock principle of wanting to attract attention.

MARIA GRAZIA CHIURI AND PIERPAOLO PICCIOLI ARE THE CREATIVE DIRECTORS OF VALENTINO.