Olivier Assayas’ Riot Acts

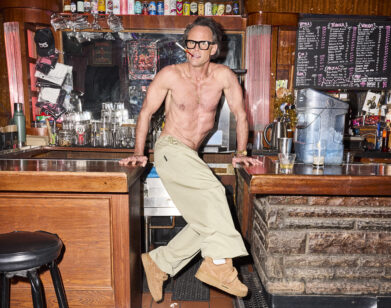

ABOVE: A STILL FROM OLIVIER ASSAYAS’ SOMETHING IN THE AIR.

“We were sick with hope, those of us from ’68,” Marguerite Duras remembers in the title essay of her last collection, Writing, published in 1993. In it, Duras muses in an unfurling, associative manner about her craft, about a separation from others, about solitude. But she also understands, and as that quote suggests, that the rippling hope gained from her participation in the the May ’68 protests in France, was as she notes, “incurable”—eternally fixed to her art.

Growing up in the countryside just outside Paris, filmmaker Oliver Assayas was only 13 in 1968. He was too young to participate in the May protests or even understand what was happening. He did, however, come of age in its wake; and his most recent film, Something in the Air, follows a group of teenage friends who interpret for themselves through film, books, art, conversations with parents, dissent, sex, and travel, the revolutionary aftermath of ’68. The original title, translated from French, is “After May.”

Still, Assayas is careful to look back without too much sentiment. Something in the Air is less about particularizing the turbulent nature of France at that time and instead relates the protagonist, Gilles’ (played by newcomer Clément Métayer) developing attitude towards the world and his place in it. Gilles’ at times wildly intangible ideas and irresolute choices about growing up, about love and his unyielding pull towards painting, and later about film, are in some ways autobiographic. Perhaps Assayas’ near two-decade, slight revisiting of his feature Cold Water, from which he reclaimed the names Christine and Gilles for Something, reflects the filmmaker’s personal and inescapable draw to that singular moment in history, its upshot, and subsequently, his own artistic pivot.

DURGA CHEW-BOSE: So I’ll just jump right in. Teenagers partying in the countryside is an image you return to. Like the final minutes of Summer Hours or now with Something in the Air and its ode to Cold Water‘s extended sequence. And often, a girl will hold a boy’s hand, confidently leading him through the woods so they can briefly escape the revelry. Why this image?

OLIVIER ASSAYAS: I think it has to do with when you deal with teenagers, the horrible truth for young boys are that the girls are usually much more mature. You are attracted to girls your age who consider you a small boy. I think it’s really something that’s at the core of any movie that would deal with that specific age in life. Unconsciously, I always come back to those images of youth and nature, and running around, which is obviously somehow autobiographic. I grew up in the countryside—I mean, it was the suburbs of Paris, but at that time it was still the country. When I think of the ’70s and the youth of that era, these are the images that come back to me.

CHEW-BOSE: Also, looking at Summer Hours in relation to Something in the Air, both films’ relationships to art are approached very differently. There’s that scene near the start of Summer Hours, where the father, Frédéric, is explaining to his teenaged kids that two Corot paintings that their grandmother owns will eventually belong to them. They are indifferent. Whereas in Something, art is a romantic passion of Gilles’, and a pursuit he would very much like to follow. They are two very different types of young people in two very different times.

ASSAYAS: Yes, they are kids from two different eras. And I myself am a bit of both. I’m not a hundred percent sure kids from the ’70s would have reacted the same way as kids of today to the paintings of Corot. At the time, in the ’70s, there was not that rift between the art of the past and modernity. There was still a notion, at least when I was growing up, that the art of the past had really something to say to us. It still does, but it’s less and less popular with teenagers. But also, Gilles’ paintings are inspired by my own paintings—he’s a better painter! He does things the way I did them; the history, the evolution of his work is very similar to the evolution of my own work. Meaning, what I started doing was really abstract painting, just you know, dripping ink and having a very violent relationship with a piece of paper. And then I gradually moved towards doing things that were slightly more figurative. I think that the center of a movie like Something in the Air is really the evolution of the history of the relationship to art. And if I had to sum up genuinely what the movie is about, is how it starts from Gilles’ abstraction to accepting he will one day become a filmmaker, and that cinema in a certain way can be considered as a superior form of representation. It’s really the undercurrent of the film.

CHEW-BOSE: Sound in the movie. From the repetitive sounds at the factory, to the mechanical copying machine, to the scene at night when they vandalize their school and every spray can, ladder being climbed, every poster being wheatpasted onto the wall can be heard so clearly. You were very careful which scenes would have music and which ones would be completely silent save the characters and their actions.

ASSAYAS: The way I remember it, when you did that kind of minor mischief at night, what was striking was the silence. It was the way anything you do, echoes in the night. It’s very pure—you only once in a while hear a train passing in the distance, or once in a while you have a car, but it’s far away. Ultimately, you hear your own footsteps, and they are extraordinarily defined, and precise, of course, very scary too. So yes, of course, it was extremely important to recreate those sounds. In terms of those factory sounds, it’s more a dimension of the printing plant where Jean-Pierre works, where all of a sudden there’s this machine… it’s a behemoth! It was extremely loud. The loudness of the machine related to the aggression of factory work. When they are printing the leaflets in this militant office, to me, the sounds were very much about reminding me of those times. I hadn’t heard those sounds for ages. When I first heard that copying machine, the whole mood, the whole feeling of that situation came back to me. These sounds had the same role as the songs for me. It brings back very precise, very vivid memories.

CHEW-BOSE: What do you hope young people from my generation might get from this film?

ASSAYAS: You make movies hoping that someone will appropriate it; I’m not sure what, ultimately. Movies are ambiguous, and they have many purposes. And at the core of this film, again, it says something about how you become an artist. So it could be a clarifying experience for a viewer of the film—that would make me extremely happy. But it’s also reviving a time that is not that far away that was defined by incredibly different values. The 1970s in relationship to the late ’60s, and specifically in France in relation to May ’68, was very different. In France, people are obsessed with the May ’68 revolution. It’s being worshipped, which was not the case in the early ’70s. There was a notion that May ’68 failed and it was a rehearsal for the actual revolution to come. That’s what kids were obsessed with, and they were convinced it was possible, that one generation had the power to turn society upside down. And it was a fact. It was not a dream or perceived as utopian, because not only we believed it, but the authorities also believed it. The cops on the street believed it. The headmasters believed it. Everybody was kind of scared. There was a certain level of antagonism that made things electric. So, what I am saying is that what we don’t have today is a similar point of reference. You don’t have a revolution that came close to happening, that can serve as a blueprint. What is interesting from the 1970s perspective is that the ’70s were utopian. They did not believe in transforming society or adapting society to more human or more generous values. They believed in just tearing it down. To me it’s really striking because when I visited Zuccotti Park, it really struck me that it felt like whatever was going on in the ’70s. It looked like it in ways unlike anything I had experienced since. All of sudden, it was very disturbing in many ways, and fascinating too. But what also struck me was how realistic the demands were. What Occupy is saying is common sense. It’s what any decent politician should be about. What Occupy is saying and what should be in the mouth of every politician, has to come from the fringe—has to come from the margins. There is this faith in the possibility to reform society. The ’70s didn’t care, hated the very notion, of reforming society. Today I am excited by what is happening because at least you have young people on the street who are saying things that need to be said. You can’t say that nobody is saying it. The hope is that a minority can have an active role in transforming the future, and you see that with Occupy Wall Street and in a certain way with the Arab Spring, and with Pussy Riot.

CHEW-BOSE: Did you have conversations like this with your actors?

ASSAYAS: I don’t like having too many conversations with my actors, once I have cast them. I decided to try and give them as little as I can in terms of the psychology of the characters. Yes, I was trying to give them some insights into the logic of what the ’70s were about, but much more basic.

CHEW-BOSE: Perhaps my favorite character was Laure, because there was something ineffable about her, as though she was a memory from that time rather than an actual character. She sort of personified that era. She is so important to Gilles’ character, and in that way, she drives the movie forward…

ASSAYAS: Carole [Combes], who plays Laure, she was the most difficult character to cast because she had to be, like you said, she has to be here and not here, real and not real. She needed to have in her the very spirit of poetry. At least you have to project that. So it was a very difficult choice, and I think Carole is amazing. She’s very young but she has a maturity and way of being, and she has a kind of mystery that very few kids I met had. And I would have a hard time exactly describing it. She could embody whatever Laure embodies, which is ultimately what connects Gilles to art. And she resurrects—the film is about her resurrection.

SOMETHING IN THE AIR SCREENS AT 6:30 PM TONIGHT AT ALICE TULLY HALL AS PART OF THE NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL, AND OPENS IN LIMITED RELEASE IN SPRING 2013.