New Again: Trainspotting

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

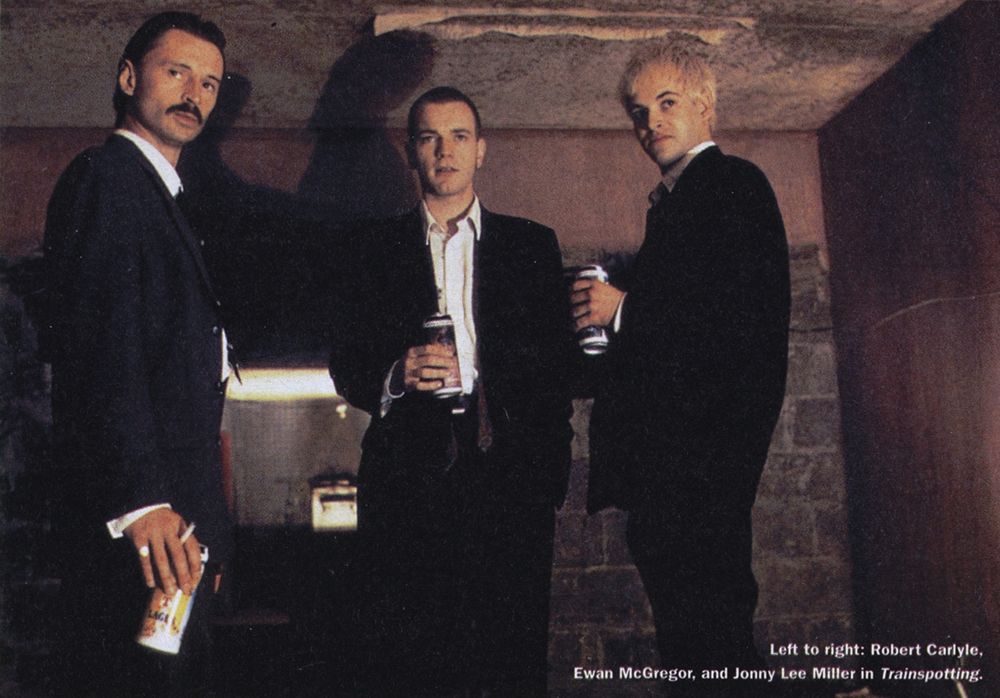

In 2009, director Danny Boyle won an Oscar for his film Slumdog Millionaire. He’s directed Hollywood power list-worthy stars such as Leonardo DiCaprio (The Beach), Cameron Diaz (A Life Less Ordinary), and James Franco (127 Hours). Yet his most famous film to date remains a fairly low-budget, mid-’90s Scottish film about heroin addicts starring a young Ewan McGregor, Trainspotting.

When the film was first released in 1996, we devoted several articles to the cult film and its star, McGregor. Seventeen years later, Boyle is determined to return to Trainspotting and adapt Irvine Welsh’s sequel, Porno, with the original Trainspotting cast in time for 2016. Time to revisit our spread. —Emma Brown

The Other Side of the Tracks

by Graham Fuller

Get ready to go loco over Trainspotting, the movie that’s blown a lot of steam up a lot of people’s assumptions about cozy British filmmaking.

Trainspotting has just arrived in American movie theaters with its pistons throbbing and its bells clanging. Adapted (as everyone must know by now) from Irvine Welsh’s 1993 vernacular novel about the young disciples of Edinburgh’s heroin culture, it’s a dreamy, surging, and scatological tragicomedy that goes easy on the “tragi” part; there are many laughs to be had from Danny Boyle’s movie. If one can just get past the heroin-induced cot death, the squalid demise of a junkie, the scenes of cold turkey, and vat loads of what the Scotts call shite. It was released in Britain in February and created more commotion there than any previous Scottish film.

But is Trainspotting truly Scottish—and, if so, what does it tell us about Scottish culture—or is it more accurately British? Andrew Macdonald, who produced the film, had this to say about it in the February issue of Sight and Sound: “I suppose I feel, because I live in London now, that Trainspotting is a British film.” And then, in the same breath, “In a way, I still see it as a Scottish film.” Scottish regionalists may be equally confused. Before the film removes to London, it unfolds mainly in Leith, Edinburgh’s port area. Yet it was filmed largely in Glasgow and financed by the London-based TV network Channel 4. Its indigenous is subtly skewed, the result of it being made by outsiders looking in rather that insiders looking out.

If there’s any sense of a Scottish identity in Trainspotting, it’s a thing to be escaped from, not embraced. As the protagonist, Renton, acknowledges in Welsh’s novel when he visits London: “Ye can be freer here, no because it’s London, but because its isnae Leith. Wir all slags on holiday.” And here’s the peripatetic Robert Louis Stevenson back in Edinburgh in 1867 between trips to the continent: “I wad down at Leith in the afternoon. God bless me, what horrid women I saw. I was sick at heart with the looks of them. And the children, filthy and ragged! And the smells! And the fat, black mud! My soul was full of disgust ere I got back.” So much for the Scottish-heritage industry endorsed by Rob Roy and Braveheart.

Trainspotting, the movie, gives us a Leith—albeit a Glasweigan Leith—essentially unchanged from Stevenson’s day. But, if it weren’t for the characters’ insistent brogues and the specifically Scottish hard-man machismo of the psychotic Begbie (Robert Carlyle), the movie might just as well be taking place in Moss Side in Manchester, Toxteth in Liverppol, or any other inner-city site of the flourishing British drug economy of the late ’80s. Or, it could be happening in—as a charcter in boyle’s Shallow Grave (1994) describes New Town, Edinburgh—”…any city, anywhere.”

Trainspotting’s Engine that Could

By Mark Jolly

Introducing Ewan McGregor, the Scottish actor whose sly and dreamy style keeps eyes glued to this summer’s most energized and arresting movie

As a child growing up in a small Scottish town, Ewan McGregor wanted to be everything that his actor uncle, Denis Lawson, was: someone different from the rest of the crowd. McGregor’s performances in two of the most daring films of the ’90s—the sardonic thriller Shallow Grave and the Brit movie-of-the-moment Trainspotting—have now turned that aspiration into reality. Among a glut of young Hollywood-bound U.K. actors, McGregor has singled himself out with his instinctive gift for ambivalence—an ability to tiptoe across the psychological high-wire between soulful and nihilistic, cocksure and charming, victim and victor.

In Trainspotting, adapted from Irvine Welsh’s novel and made by the Shallow Grave team of writer John Hodge, producer Andrew Macdonald, and director Danny Boyle, McGregor plays Renton, an on-and-off heroin addict who can’t decide whether to clean up or regress in the company of his loser friends in working-class Edinburgh, and later in London. Renton is dreamy, sharp, troubled, and calm, seemingly at the same time, and you never know where you are with him, as he never knows where he is with himself. It’s an understated portrayal of an essentially rootless character—yet a magnetic one.

While still in drama school, McGregor was chosen to play a young cockney conscript who daydreams of being a rock-‘n’-roller in Dennis Potter’s TV miniseries Lipstick on Your Collar. He was the ambitious seducer Julien Sorel in Scarlet and Black for the BBC, and in Shallow Grave, the smart-ass journalist who winds up staked to the floorboards with a demonic smile and a kitchen knife through his shoulder. He brings his urbane side to Jane Austen in this month’s Emma, and has key roles in Peter Greenway’s latest film, The Pillow Book, and the recently completed American movie, Nightwatch. “Choose a life. Choose a career,” Renton sneers at the beginning of Trainspotting. Ewan McGregor is making the most of his choices with no such need for ironic reflection.

MARK JOLLY: Ewan, what’s your understanding of the title Trainspotting?

EWAN McGREGOR: The first thing is that heroin users mainline along their arms and inject up and down on the main vein. “Station to station,” they call it. And for addicts, everything narrows down to that one goal of getting drugs. Maybe “trainspotters” are like that, obsessively taking down the numbers of trains.

JOLLY: I heard you lost 28 pounds to play Renton in the movie.

MCGREGOR: Yeah. My wife was my dietician. Basically I just stopped drinking beer and the weight fell off me. It’s nice playing with your physicality.

JOLLY: What research did you do?

MCGREGOR: I read books about crack and heroin. Then I went up to Glasgow and met people from the Calton Athletic Recovery Group, which is an organization of recovering heroin addicts who don’t use methadone to come off [the drug]; they just come off day by day. They also play a lot of soccer.

JOLLY: Did it feel strange befriending these ex-junkies so you could pretend to be like them later?

MCGREGOR: No, because they knew the score. They’d read Trainspotting [the book] and loved it. We developed a working relationship with them.

JOLLY: What’s your own experience with drugs?

MCGREGOR: I’ve never shot drugs. But we did “cookery” classes at Calton. It was six actors sitting around a table with little bits of glucose powder. I always imagined that cooking a shot was ritualized, and you had to be very precise with it, but Eamon [Doherty], our drugs advisor, said, “No, it’s not a ritual—it’s a pain in the arse until you get it into your arm.” It was weird how mundane it all was.

JOLLY: The scene in which you get injected—is that your arm?

MCGREGOR: Yeah, but in that scene I’m getting an AIDS test, not shooting heroin. It is my arm, and that was quite good actually. After pretending to shoot up for six or seven weeks, it came as quite a relief to have a needle in my arm. I was like, “Go on, stick it in me.”

JOLLY: And while we’re talking about specific scenes, what was it like sticking your head—in fact, your whole body— into a toilet?

MCGREGOR: It was a set, of course, but it didn’t really matter. It looked disgusting, and by the end of the day I wanted to get out of there.

JOLLY: What did you learn about the drug culture that surprised you the most?

MCGREGOR: There’s a certain kudos about smack in Britain, a kind of romanticism—it’s the one you really shouldn’t do. They call it “the big bad one.” Once I started working on the film I realized there is no romantic aspect to being a heroin addict at all. Listening to these guys’ experiences, the point of despair most of them had reached was extraordinary.

JOLLY: Wasn’t there a danger that the film could glamorize heroin, especially with all the hysteria that greeted it?

MCGREGOR: I’m absolutely fine about that because I know it doesn’t glamorize heroin.

JOLLY: But the film looks very slick.

MCGREGOR: Films do look slick—but Trainspotting doesn’t make the heroin look slick. The reason people get upset about it is because they don’t want to think about drugs as being the least bit pleasurable, but heroin makes you feel great—apparently —and we showed people who do it feeling great in the movie. But then we show what happens if you get addicted, what happens to you as you die.

JOLLY: Do you think people have preconceived notions about addicts?

MCGREGOR: Yes. They want to think that heroin addicts are bastards and bad people, which they’re not. They’re people with problems and they choose heroin as a way out of them, as some characters do in the movie. They come from housing schemes in Leith [a depressed area of Edinburgh] where there’s never been any hope or future for them. Their parents and their parents before them never had a hope or future, either.

JOLLY: When Renton goes into the countryside with his friends, he gives a speech attacking both Scotland and England. When you’ve seen the film with different audiences in Britain, has it inflamed racial prejudices?

MCGREGOR: I’ve seen the film a couple of times in England, and it always got a really good laugh. Scottish audiences, of course, love the line about the English being “wankers,” although I’m not sure what they think of Renton’s ideas about being Scottish.

JOLLY: You went to a school where your father was a teacher and your brother was the head boy, and you left at 16 to pursue an acting career. What did you have to do to convince your parents that this was something worthwhile?

MCGREGOR: I didn’t. They just let me do it. I was doing badly in school and kept getting sent to the headmaster, which was probably starting to get embarrassing for my father. So one night—I remember it was dark and raining heavily—my mum said to me, “You can leave if you want to.” Suddenly, my horizons widened into CinemaScope, and within a week I was working backstage at the local repertory theater in Perth. I did that for six months, and I learned an awful lot about life and about growing, because I hadn’t really seen anything before. I met gay people and I met people who were having affairs. I gobbled it all up—it was brilliant.

JOLLY: I believe you’d known from an early age that you wanted to be an actor.

MCGREGOR: I decided when I was nine, I think. I probably got it from my uncle, Denis Lawson, who acted in Local Hero [1983] and who does a lot of TV. In the ’70s, he used to come up to Creiff—the small town I was brought up in—from London, and he’d be wearing sheepskin waistcoats, beads, long hair, and flowers; for a while he didn’t wear shoes. I used to think, Who the fuck is this amazing guy? I just wanted to be like him because he was so different. Later on, Denis worked with me on speeches when I was applying to drama school.

JOLLY: You seem to have cut a niche for yourself playing characters who use cockiness or sarcasm as a weapon against the world. What draws you to those characters?

MCGREGOR: I don’t pick characters because they’re sarcastic or cocky; I just pick them because I like them. It’s quite a cynical age in Britain at the moment. If you look at our chat shows and comics, they’re very much into humiliating people. But in Emma, I play Frank Churchill, the unsarcastic guy who comes in about halfway through the movie, so I’m lovely in that. I’ll probably be hated by movie audiences all over the world for being the really annoying charming guy.

JOLLY: Do you have a reputation for being sarcastic?

MCGREGOR: No, I don’t think so. [asks his wife, who’s in the room] Do I have a reputation for being sarcastic? [pause] She says no.

JOLLY: Of course, Renton is vulnerable as well as cocky.

MCGREGOR: He’s not that vulnerable. He cares about his girl and his parents a bit, but not much else. He’s quite happy when he’s on heroin, and he’s miserable when he’s off it until he goes to London and becomes an estate agent. Irvine Welsh had done that himself. He went from junkie heaven in Edinburgh, in the late ’80s, to boomtown London.

JOLLY: The characters are a lot nicer in the film than they are in the book.

MCGREGOR: Renton is so nihilistic in the book that I don’t think you’d want to watch him like that onscreen. He’s been humored up a bit, but I don’t think anything’s been lost as a result of that. Irvine Welsh seems happy with the film and that was important.

JOLLY: Do you think American audiences may be a bit shocked by Trainspotting after seeing more traditional images of Scotland in Braveheart and Rob Roy?

MCGREGOR: It’s not done anything for the Edinburgh Tourist Board, that’s for sure.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE AUGUST 1996 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.