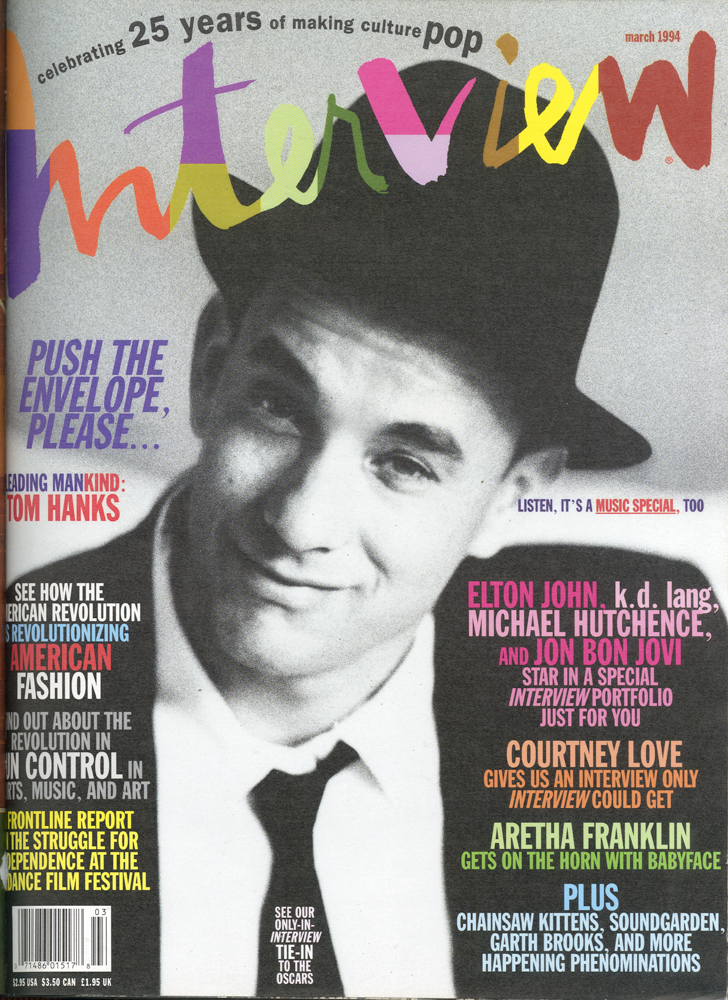

New Again: Tom Hanks

If you say the name Tom Hanks to five different people, each person will most likely come up a different mental image. As part of blockbuster franchises like Toy Story and with a filmography that includes the leading roles in Saving Private Ryan, Castaway, and Forrest Gump, Hanks is undoubtedly one of the most successful and recognizable living film actors. He has won two Academy Awards and been nominated for three more since his film debut in 1980. In 1994, a few months before the release of Forrest Gump, Hanks sat down with Interview Editor-in-Chief, Ingrid Sischy. The two discussed stardom at a point when Hanks’ career was poised to explode as well as his roots as a young actor and how he redefined clichés surrounding Hollywood’s leading men. —Wil Barlow

———

INGRID SISCHY: I want to begin by asking you about glamor, and about being a leading man in the movies today versus the past. One of the things that was so amazing about the old days, when studio photographers helped create the images of movie stars, was that there were formulas that could be counted on to work. They made the women and men into something like marble, untouchable figures. There was a sense of the distance that was required in order to keep glamor glamorous. Now we live in an age where stars have become more like public property than fantasy property. A lot has changed since the time when to be a Hollywood leading man meant to fit a certain formula of maleness. Talk to me about what those guys meant to you, and about yourself in contrast to them. Who was glamorous to you, and what is glamorous now?

TOM HANKS: Man. I thought Fireball XL-5 was really cool. I thought Batman the TV show was really cool. The other was the stuff of weekend TV. It seems to me that a Charlton Heston movie or a Burt Lancaster movie was on every Saturday night. Those guys were the guys who were bigger than life. The older guys—Clark Gable, Gary Cooper, and those types before the war—were already icons. The idea of being a movie star like them was forever altered. How do you aspire to be something like those guys? That would be like saying, “Do you want to be one of the Twelve Apostles?” I never thought I was glamorous. My association with the creative process began at probably the best time for American movies, which was the 1970s. You can’t make 90 percent of those movies now. You can’t make Five Easy Pieces; you can’t make Chinatown; it would be hard probably to get The Godfather made now. The list goes on.

To me, the epitome of glamour, the absolute… As a matter of fact, if I had my way, as far as fashion and style and everything like that, I’d look like the Beatles did on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. I’d be in a skinny-lapeled suit with a white shirt and a black tie and pointed shoes. That to me is the absolute be-all and end-all of what I think is glamour. Maybe it’s just because I was living in a string of rented houses and apartments when I was growing up.

You were talking just now about movie stars as public property. I think part of the reason is that there are a lot of channels on TV, so the search for product is ongoing. And a very easy product is talking about who is out there right now. There’s an entire channel that’s just dedicated to who showed up where, which is fine, but the fact that it’s on TV magnifies the content and iconography of being a movie star… According to most of the media, what does it mean today? It means limousines, it means autographs, it means sunglasses, and it means incognito vacations and bodyguards and houses with gates. After that, what’s fun about the icon? You have to find out the chinks and faults that make them absolutely normal. With some people, you’re just dying to see them fall down, you’re just dying to see some sort of crack. Some are built up and turned into bigger movie stars, and with others there are people who just want to see what’s wrong with them. A lot of it’s what makes for good copy at the time. It’s the sort of news you hear about somebody getting drunk and throwing up outside a restaurant somewhere. That sort of attention is something that is not warranted, but it’s there. There’s nothing you can do about it. You cannot control your own spin. You cannot foment what your image is going to be.

SISCHY: Go on.

HANKS: The only way you can truly control how you’re seen is by being constantly honest all the time. But now, if you’re going to be totally honest all the time, does that mean that you have to throw out your family dysfunctions every time you appear on the Oprah Winfrey show? Does that mean you have to go into rich detail over what difficulties you had overcoming something as a youth, over how and why your last marriage blew up? Or, instead, are you just going to say: “Well, of course I had difficulties when I was growing up. Who hasn’t had difficulties growing up?” That’s another way of being honest. But you can’t control anything by putting out some all-encompassing faux presentation of who you are. Sooner or later, they’re going to find out that you’re not what you were saying you were. And when that’s the case, man, anything of what you had put out there before doesn’t matter. I can’t look at those Rock Hudson/Doris Day movies without thinking, “Rock Hudson was a gay man who sadly had to have a phantom marriage and died of AIDS.”

SISCHY: Truth—the biggest, the most obvious, yet the most complicated subject of our time.

HANKS: Macro truth. It sounds real easy, but in the context which we’re talking about it, it’s hard to do.

SISCHY: Because of what’s done with that truth? Or because the world might not be ready for it? Or because it may hurt others?

HANKS: Yes. All of that. And here’s another reason that it’s hard. There’s no training for having the kind of attention on one that we’re talking about. I think it was Bill Murray who said there’s no training for fame. When you first have the glare of the spotlight of public attention put on you, it plays around with your head. You have to get used to it. You’re literally at a lofty height, and it’s as though you don’t have enough oxygen. As soon as somebody stick a microphone in your face and says, “Who are you and how did you get here?” …Man, the first time that happens, it’s a narcotic-like trance that you can fall into. You can see it happening every time some film festival ends, every time the Olympics or the Super Bowl is over, every time somebody is thrust in the spotlight for the very first time. It alters their consciousness. Having to validate one’s success leads one to question why and how one got there. The sense of accomplishment is replaced by celebrityhood and the identity crisis that comes with it.

If I was actually to give you a rundown of why you and I are sitting here talking, going back to the beginning, you’d probably realize one tiny element could have been removed from the timeline and that would have changed the course of everything. It was a string of the goofiest coincidences that you could imagine, buttressed with knowing somebody who gave me a shot, buttressed next to the times that I absolutely choked and went off with my tail between my legs. That’s the case with everybody. But how am I supposed to answer what I am really like when the questions are put the way that they so often are? I’m a mystery to myself still, day in and day out, and I’m still trying to figure it out.

SISCHY: That’s what’s great about life, isn’t it? That our understanding of ourselves and of others isn’t a fixed thing, that we surprise each other and ourselves? Was it a surprise to you that you became an actor? Was this a dream you always had?

HANKS: No. I went to a big urban public school in California, in Oakland. Two thousand kids, a big drug culture, very well integrated, 1970s. The rules were being completely redefined. As a matter of fact, I think everybody had given up by then. Students had fought their battles in ’68, ’69, and ’70; by the time I got there, the attitude was, “Do whatever you want, just don’t burn the place down,” which, actually, some people still tried to do. In my sophomore year, I ran track, I tried to learn how to play soccer, and I started going to this youth group in a church that a lot of my friends belonged to. I mostly just wanted to get out of the house; the house wasn’t a good place to be. At school they did two plays—a fall play and a spring musical—and a friend of mine, who was this super-genius guy, was playing Dracula in Dracula. Watching him, I was utterly envious of his having the experience up there. I sat in the audience and thought, “How come I’m not up there doing that?” When they opened the curtain, it was just so full of life; friends of mine were on the stage and running the lights, and I knew most of the people backstage. Up until then I’d had no clue that acting was ever an option. The next year I signed up for the drama class and tried out for the plays, and got into them, and had more fun than I could possibly imagine. It was an incredible group of people, some of whom are still my friends. I got into this eclectic group that was kind of rootless and cliqueless.

When I went to community college I would always treat myself to a drama class a quarter. But I hadn’t landed there yet. I hadn’t made the overall connection. Then one day my friend John Gilkerson came by to see me and asked me what I was doing. I told him I was a bellman in a hotel, and he said: “Shame on you! You’re not doing anything. You should try to do plays!” And that was really the beginning. By then I’d been going to see the theater and my desire to be a part of it had become even stronger. I’d go alone because all my friends were skiing or at basketball games. So I tried out for one show and got the part playing George in Our Town. Then I went to California State University at Sacramento, the only institute of higher education that I could get into where you could do plays. I stage-managed shows, was a carpenter for shows, and acted in them. Also I started hanging out in a place attached to the theater called the Green Room in Sacramento, where everybody had an entrance, everybody was a star. It was a great mix of people.

SISCHY: Do you think it’s possible to have that kind of group of friends in the world you live in now?

HANKS: Having been rootless for a while, I think I’ve finally landed in a couple of concentric circles. I’ve been married for five years, and it’s happened within the last four and a half. I got lucky in love first, and now I finally got lucky in friends. I actually think I needed the foundation of a family before I got a group. I had to take that very, very slowly. It goes back to what we were saying about the imbalances that come with fame. I’m kind of ashamed of how many possibilities probably went by the wayside. Our group is the same kind of group that I was in at high school or in the Green Room at Sacramento. Everybody gets an entrance, you know, whether they’re actors or not. Everybody has that kind of presence that emboldens the table, and we do stuff like old people do. We have cocktails and dinner parties and stuff like that. We go on vacations that are hanging on the edge of disaster all the time, because anything could happen during them! It’s got that same bona fide oomph that is based partly on the fact that we laugh a bunch and that we have an awful lot in common, partly because we’re parents. It’s also an intellectually powerful kind of atmosphere to be in. Some of these people are famous or incredibly accomplished, and some of them aren’t.

SISCHY: When your name comes up, people say, “Oh, he’s great.” You don’t seem to divide up opinions the way a lot of actors and actresses do.

HANKS: Right. I don’t threaten any man’s sense of virility, or any woman’s sense of security or decorum. I think I’m a gentleman, you know. But a sloppy one! [laughs]

SISCHY: It’s hard to cross all those boundaries that you cross: for example, to be a man who has real human appeal to both men and women. I’m interested that you say it’s because you don’t threaten people. I think it’s more a question of your being without all these notions and defenses that usually turn people into types instead of individuals with many sides. For example, you seem free of the usual clichés of masculinity, and sitting here talking to you, I’m struck by the ease in the atmosphere between us. Tell me about how growing up at the same time that women were forcing the culture to grow up in terms of its attitudes and prejudices about them affected you.

HANKS: I never thought of my relationship to women in terms of a feminist point of view, because what’s to think about it? By the time I was an adult, I didn’t have to make myself respect women. When I made Big with Penny Marshall, it wasn’t the first time that I had worked with a woman who was in a position of power, but there were a lot of questions from the outside like “What’s it like being directed by a woman?” I didn’t understand the question. Her personality is very unique; that’s all there was to say. The most commercially successful movies I have done have all been directed by women. They were in charge. They made the movies! I graduated from high school in 1974, so I was operating with a relatively modern view of the world. The ideas that were put forward by the great feminist thinkers—and I don’t even know who they are—were just part of my life.

SISCHY: So your art imitates your life. Many of the roles you play fit your experience, and your view of the world. To be a Hollywood leading man who is led by feeling and not image, that must have gone against all the clichés of sexiness.

HANKS: I’ve always liked those women who go after the brooding loner in the corner. There was a while there where me and my funny friends were always complaining because funny never got us laid. But then something happened, and I was funny and I got laid, and that was quite a moment of power, I suppose. I didn’t have to try to be the brooding loner anymore. I could just get by on being funny. But that’s something different. Look, I have bedded seven women in my life. That’s a paltry sum. I have talked to guys who are into the high three digits, if not actually four digits. I’m not even off of two hands. I think I have a degree of sexual confidence that is kept in its proper perspective and that is not flaunted. I know what that comes out of, because for years I had no sexual confidence, for years I was lonely. I didn’t feel like a dope because of that. I don’t feel as though I’ve missed out on anything.

SISCHY: You talk about loneliness a lot.

HANKS: Because I felt really lonely for a real long time. That’s why I saw that my wife saved me, because I don’t feel lonely anymore. I did right up until the point where she crossed my path.

SISCHY: Do you think one person can save another?

HANKS: I think the right person can, but that right person is hard to find. It’s not about validating another person; it’s that the union of the two of you is better than the actual sum of the two of you. You don’t just add two people; you multiply. That’s what I think I’ve got. And it’s not a purely romantic thought; it’s much better. Rita [Wilson] and I have been through a lot as a couple, and certainly as a husband and wife. It takes a while to pound out a relationship, but I think that process ends up being the great hope. Somehow, it’s the great hope that is reflected in a lot of the movies that I do. It doesn’t matter what gender or what sexual orientation; it doesn’t matter.

SISCHY: And your movies also have a lot to do with loneliness and with being saved from it in all different ways. Obviously, you’re attracted to stories that have to do with these kinds of things.

HANKS: The cinema has the power to make you not feel lonely, even though you are. You can go in a lonely human being and you can see something that for two hours, and however long the afterglow lasts, can make you feel as though you actually belong to something really good.

Why do I take the jobs I do? I think part of it is because they reflect what I think is the truth somehow. I thought it was great that A League of Their Own did nothing to adhere to the usual movie formulaic relationship between a guy and a woman. We actually did have a sexual relationship at one point, but they cut it out of the movie because they found it was much better without it. The story of my guy’s side of it was that he respected Geena Davis’s character, who proved she was a ballplayer. I thought that to stick with that was a cool thing.

SISCHY: And your next film, Forrest Gump?

HANKS: It’s about a guy with a limited I.Q. who operates at the speed of his own common sense. He lives an amazing life and sees amazing things, but the purity of how he sees the world was what I thought was amazing about the screenplay, and what he goes through to get to the point that we’re all at. All the great stories are about our battle against loneliness: Hamlet is about that; so is The Importance of Being Earnest. That’s what I always end up being drawn toward.

SISCHY: You were drawn to Philadelphia, a movie that is ripe with the themes of isolation, loneliness, and love, as well as injustice and hate and ignorance of certain ways of loving. In it there are people who are enlightened about homosexuality, people who drop their habits of prejudice, and people who don’t. The story unfolds because of AIDS, and I’m curious whether or not you think Philadelphia has helped to civilize people in general about AIDS, and also about homosexuals—who of course are by no means the only people to be affected by AIDS.

HANKS: Almost everyone I’ve met has already come to some conclusion about AIDS. They already have in their mind that either dark or light image of what it is. But because I’m the guy that’s in the movie, the first thing that comes out of the people who have talked to me about it is their incredible emotional response. More people have stopped me on the street or come up to me in airplanes or sidled up to me in restaurants to talk about this movie than any other job I’ve done, and almost all of them have said something like, “Thank you for doing it.” Often they have some connection that is much greater than I have to AIDS.

SISCHY: Have you had the kind of anger directed against you that people with AIDS experienced so often?

HANKS: Not much. After I appeared on the Letterman show, I got a letter that called me “a liberal liar.” During some of the press junkets, I have been taken to task for some of the choices in the movie. But no, I have not received anything from the religious right, which was the quarter that probably worried the studio [TriStar] the most.

SISCHY: When somebody says to you, “Thank you for doing this,” do you feel guilt about being treated that way? After all, you played a part; you haven’t gone through what people go through who are sick.

HANKS: I don’t feel guilt. But I feel unworthy. I feel that I don’t deserve to be thanked for this. But I think I understand why they’re saying it. Obviously, there’s been so much more said about AIDS by others than what we revealed in our two-hour Hollywood movie, but there is something that is tangible, and at the same time hyper affecting, about a mainstream movie up on screen. It becomes visceral, textural, more so than a theater piece, more so than a documentary, or a book or magazine story about it. That’s the power of the movies, and I think that’s what they’re thanking me for. They are thanking me for the wide-screen illumination of something real.

SISCHY: Also I’m sure some of the people are thanking you for being a mainstream star who has taken on a role about a subject that has been tragically stigmatized and misinformedly ghettoized.

HANKS: Yes, the general attitude has been that AIDS is somebody else’s concern, something that doesn’t touch all of us. So when we make the kind of movie that has the big ads in the newspapers, whether one’s going to see the movie or not, it forces attention on the subject somehow.

SISCHY: I’d be missing the perfect end to this interview if I didn’t ask you whether it’s crossed your mind that you’re going to get an Oscar for Philadelphia. How do you feel about it, about winning, about losing, about the whole shebang?

HANKS: In the abstract, it’s still this amazingly special thing. I know how hard it is in order to be one of those guys, and I know how you have to do something beyond the pale in order to rate. But it’s also a horrifying prospect. It’s very scary. Part of the reason that it’s nerve-wracking is because once that machine gets going, you have to deal with it. Essentially, you’re looking at nearly two months of having your nerves wracked, no matter what. If it happens, then it happens and it’s something to deal with. And if it doesn’t happen, then it’s the thing that was supposed to happen, and you’ve got to deal with that. I am powerless to change anything, except the way I look at it. It’s probably going to cost me some sleepless nights. And I try to avoid sleepless nights, now that I am 37 years old and have had my ass kicked as much as I have.

SISCHY: Have you had it kicked?

HANKS: Of course. I haven’t talked about it much, because my problems are paltry compared with an awful lot of other people’s. I remember being 13 and 16 and 19 and 24, and hearing people who were in the position I am in now go on about how hard they had it, and I thought, Please…

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE MARCH 1994 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.