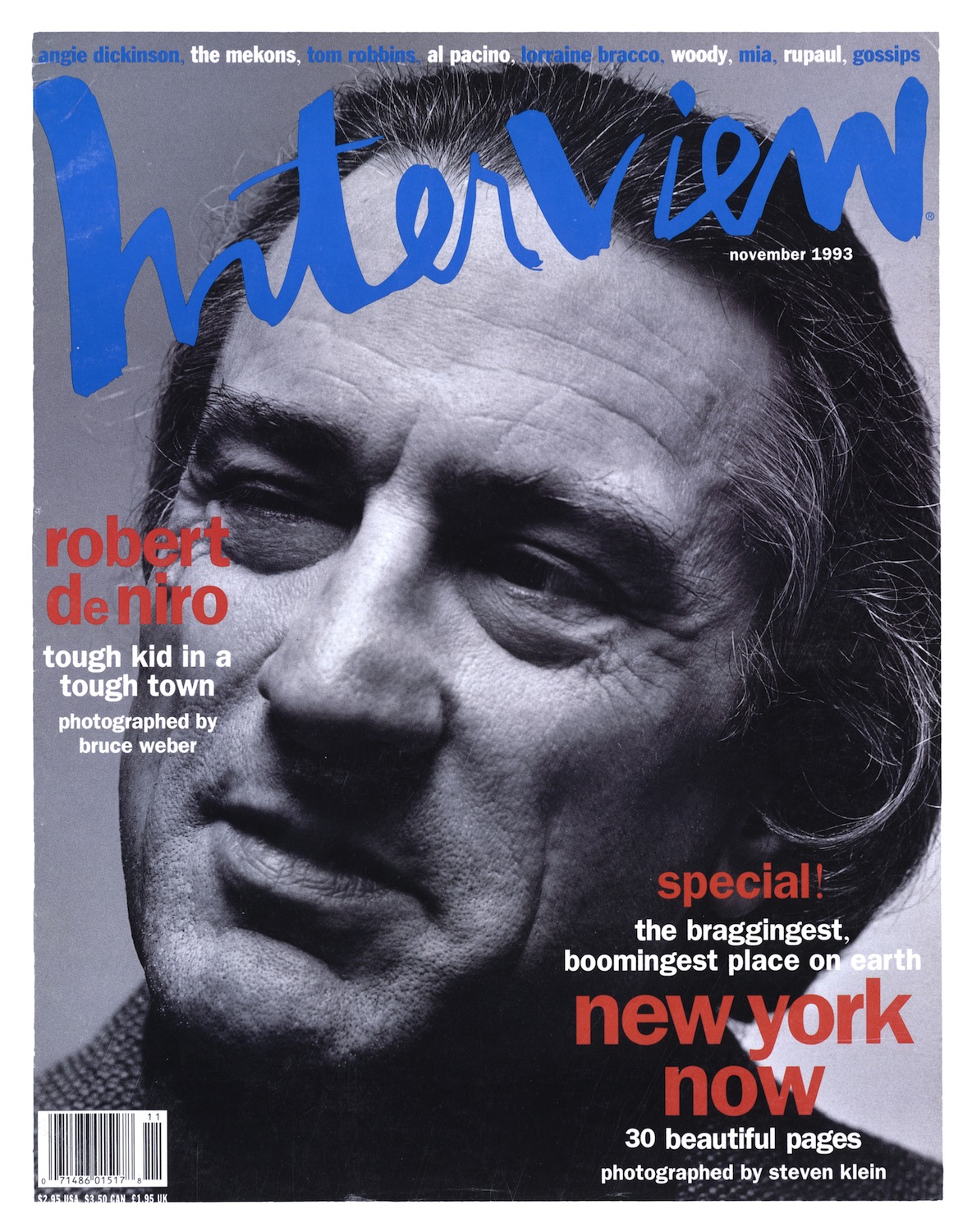

A Walk and a Talk with Robert De Niro

Interview first interviewed the notoriously sphinx-like De Niro in November of 1993 to discuss his directorial debut, A Bronx Tale. In the interview (reprinted below), De Niro discusses his downtown roots and the process of creating a truly authentic New York film with Peter Brant and Ingrid Sischy. A true native son, De Niro reasserts himself, and his city, as the center of the universe.

———

PETER BRANT: I was sitting with Dennis Hopper last night and he said, “I think the thing people will really want to know about Bobby De Niro is, when did he get the first hint that he wanted to be an actor?

ROBERT DE NIRO: I was about nine or 10 or something. I don’t remember what made me want to be an actor. In fact, I’m always curious. If Dennis were asked the question, he might say, “It was this or that that made me want to act,” but I just don’t know. I know I saw him when I was 16. Did he tell you the story?

BRANT: What story?

DE NIRO: I saw him when he was doing Mandingo with Franchot Tone, like, 32 years ago.

INGRID SISCHY: What was Dennis like?

DE NIRO: He was a brilliant young actor at that time. You know, I would go backstage and watch.

SISCHY: And what happened?

DE NIRO: It was just the way it was.

BRANT: [aside to Sischy] The first time Bobby met Dennis, a beautiful girl came up to Dennis and asked him something about acting. [laughs] Bobby, did your parents have any problem with your wanting to be an actor?

DE NIRO: Not at all. They were both supportive. They would never tell me no. My mother worked for a woman, Maria Ley-Piscator, who with her husband founded the Dramatic Workshop, which was connected to the New School. My mother did proofreading and typing and stuff or her, and as part of her payment, I was able to take acting classes there on Saturdays when I was 10. This couple had come out of Germany, and the guy went back, but his wife stayed and ran the workshop. It was a big school with a lot of actors, some of whom were able to study acting on the G.I. Bill. Brando and Steiger went there, the generation before me. When I was 15, 16, I studied with Stella Adler at the Conservatory of Acting, then I stopped again and went to the Actors Studio when I was 18. Stella Adler prided herself on teaching the Stanislavsky Method the way it should be, according to her, and I must say I agree with her standpoint. My feelings were, use a little bit of this and a little bit of that, and whatever works for you as an actor is fine.

SISCHY: Did going to acting classes make things difficult for you and with your friends?

DE NIRO: Actually, most of my friends were O.K. about it. Sometimes you figured the kids would make fun if they came to a play that you were in, so I would never even think of having them come.

SISCHY: Did watching your father try to make it as an artist have any effect on you?

DE NIRO: I saw how he was living, and so on. Struggling, I guess, for want of a better word. He led a classic New York artist’s life, in a loft, always downtown—Great Jones Street, West Broadway, Bleecker Street. What we know and SoHo and NoHo today was mostly industrial in those days.

SISCHY: Did you grow up in SoHo?

DE NIRO: Well, I always lived in the Village, but I would go to see my father. He was separated from my mother.

BRANT: Your mother was very active in the SoHo art world in the late ’60s, wasn’t she?

DE NIRO: Yes, she was. She can probably tell you more about that, though.

SISCHY: Your first movie as director, A Bronx Tale, has just come out. I notice you dedicated it to your father.

DE NIRO: Well, he passed away in May, so I thought it would be a nice thing to do—and the movie’s about fathers and sons. I love his art. I’m very proud of it, but I wasn’t an art enthusiast the way he was. It was his whole life.

BRANT: The film’s based on Chazz Palminteri’s one-man play, about a boy, Calogero, growing up in the Bronx in the ’60s and coming under the influence of a neighborhood mobster, Sonny. How did you come across Chazz’s play?

DE NIRO: My trainer told me about it four or five years ago, so I told Jane [Rosenthal, De Niro’s partner at Tribeca Productions] to go see it when she was in L.A. She said, “Yeah, it’s very good, but Chazz wants to play the part of Sonny himself if it’s made into a film.” At first, I didn’t want anything in the ingredients if I did a film of it—I wanted a totally clean slate—but I saw it and liked it and liked Chazz. While he was writing the screenplay I said, “Let me make this clear. If you give it to a studio, they’ll play you for it and people will get involved and they’ll give the Sonny part to another actor. If you give it to me now, I can guarantee you’ll be in it and we’ll set it up our own way and I’ll have more control, which is what I want. I don’t want any producer getting in the way and telling me what to do.” I didn’t want all that mishmoshing—I knew what had to be done.

I felt like Chazz had written from such a specific point. He knew that world, he knew what he was writing about. He wrote great characters, had a very good structure. I just had to fill it with the right people, and I didn’t want to use any name actors—other than Joe Pesci, who was perfect, because he knows that world too. A few other actors had parts, but mostly we worked with nonprofessionals. I told the casting director, Ellen Chenowith, that I didn’t want her to start calling the agents. I said, “It’s not going to be the usual way of casting a movie. You have to hit the streets now, a year before we start shooting. You gotta get out there and look. I know the people we want are out there. But I don’t have time to teach them. It would take forever to do that, so we just have to get the right people, who have a flair and understand what we are doing, and then put them together.” That was very important, because that world is like a medieval village. It’s a world unto itself—like it says in the film. We had a wonderful story, and the way to make it work was to have people be totally authentic, totally believable. Even their awkwardness would work for the movie. We had a kid, Marco Greco, who runs the Belmont Italian-American Playhouse in the Bronx, send us tapes of local people, and we’d bring some of them in to read. We looked in Philadelphia, we looked in Chicago—anywhere with an urban feeling. I said to the casting director, “Keep putting out the ads, on the radio stations, in the uptown papers, in the local community papers. Keep hammering away. I want to keep looking until the day we start shooting. I don’t want to stop until we’re totally satisfied.”

SISCHY: Most of the cast ended up coming from New York, right?

DE NIRO: That’s what I wanted ideally, because it’s a New York movie. We had some bonuses. Like, I read some actors to play Eddie Mush. They were very good, but then I said, “This has got to be unique.” So then we looked at some neighborhood guys who weren’t actors, so we were getting closer. Then I said to Chazz, “Maybe Eddie’s around. Where is he now? Can we find him?” And eventually Eddie came in. He read once. I aid, “We don’t have to look any further. Where are we going to find someone else like that? Never in a million years.”

BRANT: How did you find Francis Capra, who plays Calogero at age nine, and Lillo Brancato, who plays him at 17?

DE NIRO: Marco found Lillo up at Jones Beach, where the Italian kids hang out. He came out of the water and started doing imitations of Joe Pesci and me; it was really funny. Francis came to open call. He has an amazing amount of confidence and natural instincts as an actor; he’s a very lovable, sweet kid.

BRANT: What about Taral Hicks, who plays Jane, the black girl Calogero falls in love with?

DE NIRO: Taral came from an open call, too. I think she read one of our newspaper ads and told her mother she was going to go. She always had these great hairstyles, and I used to kid her about being at beauty school. She had something about her that we all noticed. She and Lillo were what I wanted. I didn’t want people who would be slick.

BRANT: You obviously enjoy finding new talent.

DE NIRO: I love to find new people. It’s not for the sake of their being new; it’s because if you find someone who perfectly fits a part, that’s such a great thing.

SISCHY: Why did you decide to play Lorenzo, Calogero’s father, yourself?

DE NIRO: I had promised Chazz the part of Sonny, and I said, “Well, I should probably play Lorenzo and help the movie get off the ground more easily.” Also, I hadn’t done this kind of part, and it’s something really different, and I wanted to do it for that reason, because people would expect me to play Sonny. As Lorenzo, I had my own experiences to draw on, and it’s something closer to me because of my kids. I have a son Lillo’s age.

SISCHY: How was it directing yourself?

DE NIRO: It was a little hard. I remember I asked certain directors, like Marty Scorsese, certain things about the way you do this or that, I also talked to other actors who has turned directors, like Danny DeVito. I guess I felt that I’d be O.K. I didn’t want to build up some kind of fear of it. Directing yourself isn’t stressful—you’re just a bit uncomfortable, because [when you’re acting], you have to set your mind in a certain way, and then you have to direct everybody else.

BRANT: Chazz is great in this film.

DE NIRO: I knew Chazz would be good, and I knew that I could direct him. No one could have been better than Chazz, because nobody knows him, he’s a very good-looking guy, a sexy leading man, and he’s just terrific. Plus, he’d be around all the time, because he was the writer. He’d be there even when he wasn’t there. We’d always be talking about a cut here, or reworking a scene there, or making it more succinct.

SISCHY: One of the strong themes of this film for me is the subject of racism and people who are trying to cross racial barriers. At the heart of the movie are Calogero, who’s white, and Jane, who’s black—two kids who aren’t going to let anybody stop them from getting together. Was that theme especially important to you?

DE NIRO: I liked the whole thing, because it was so rich. But, of course, that part attracted me. You see these two people from two different worlds: Calogero from his and Jane from hers. Then they come together, and to me that’s very interesting. There was this talk about cutting out the whole Calogero-Jane story. People would say, “Just make it between a father and a son—that’s really a story in itself,” which it was. But I felt that to take away any one of those elements would be wrong. The part with Jane is the one part that you didn’t expect, and for that reason alone I didn’t want to take it out. There’s a beginning, middle, and end to this whole relationship. It happens fast. They meet and fall in love and boom!—they come together.

BRANT: Something really happens there—not just visually but in the way you use the music.

DE NIRO: Music to me is so important, especially the music of that time. It was a great opportunity to put these old songs in, but I wanted to make sure I got the right ones. “I Only Have Eyes for You” is something I thought of for when these kids meet. The father listens to a jazz version, and the kid hears a riff from it and says, “Do we have to listen to this music? It gives me a headache.” Then as soon as Calogero sees Jane, it goes into a black doowop group singing it a cappella, then the “I Only Have Eyes for You” theme, and finally the Flamingos’ version, which is really great.

SISCHY: Do you think a movie can help fight racism?

DE NIRO: I don’t want to preach. I don’t know whether it can help or not; it depends on who sees it and what they want out of it.

SISCHY: There are good guys and bad guys in A Bronx Tale, and good and bad things happen. There’s gang warfare, the bikers get smashed up, people from different ethnic groups fall in love. It’s like an old-fashioned movie in that sense. You’re clearly attracted to a story that has a morality in which people tell each other “Follow your heart”—even if one of the people saying that, Sonny, is basically a criminal—and in which there are heroes.

DE NIRO: Sonny’s a great philosopher in his way. He might not be able to follow a moral code himself, but what he’s saying to Calogero is, “Do what I say, not what I do. Do what’s right for you.” I guess all movies shouldn’t be morality tales, but this one has the quality of a fable that winds up in a nice way. You could say it’s corny, and that’s one reason I wanted to make it as real and as romantic as possible when the kids meet—and it is real. But when the Italian kids jump the black kids and firebomb their place, that’s real. Sort of merciless, but life goes on.

BRANT: As an actor you’ve worked with great directors like Scorsese, Coppola, and Bertolucci, but what stood out to me when I saw A Bronx Tale is that you gave it your own directorial style. Something I’m curious to know is, when you were young were you interested in classical Italian filmmaking and directors like Visconti and Antonioni?

DE NIRO: No, I wasn’t. I’ve seen some of their movies, but I don’t know which ones. I should see more, but I’m not a follower of film. My father would take me to movies when I was a kid. I liked things like A Taste of Honey and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning.

BRANT: As an actor, was working with great directors always a primary concern of yours?

DE NIRO: I’ll work with a director if I think I’m going to get into a comfortable situation, and if it’s someone I respect and who respects me, even if they’re not so well known. Movies are hard to make, and you have to work toward a common ethic and do your best. You don’t want to work with people who don’t care or who are acting out some neurotic, crazy thesis on the set. Who needs it? Life is too short. But I’ve been very lucky in that area.

SISCHY: At the beginning of your career, wasn’t the point just to get parts?

DE NIRO: Yes, it was. As an actor who’s starting out, you can’t say, “Hey, I’m too good for this.” You gotta do it, because people see you, your name gets around, and it has a cumulative effect. Auditions are like a gamble. Most likely you won’t get the part, but if you don’t go, you’ll never know if you could’ve got it. I remember when I was up for Mean Streets, I ran into Harvey Keitel in the Village—we were friends—and he’d already been cast in the movie as Charlie. I had done a couple of leads in movies before so I said, “Well, careerwise, I should be playing Charlie.” I didn’t say it like a wiseass. I was saying it sincerely, but not in a way that was threatening to him. Then Harvey said, “You knew who you should play? Johnny Boy.” And that clicked. I played Johnny. Now I say to people, “If you get a part, do it.”

BRANT: You tested for the part of Sonny Corleone in The Godfather, didn’t you?

DE NIRO: I also tested for Michael [Corleone]. Everybody tested for Michael. The whole fuckin’ city tested for Michael.

SISCHY: Even Michael. [All laugh]

DE NIRO: Even Al [Pacino] tested for it, but everybody knew that he had the part and that Francis [Ford Coppola] wanted him.

BRANT: Bobby, you’re about to start work on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

DE NIRO: Yeah, directed by Kenneth Branagh. Kenneth’s brilliant and very sensible. He makes me feel real good.

SISCHY: Who do you play in that?

DE NIRO: I play the monster—the Creature, we call it.

SISCHY: With A Bronx Tale, you’ve succeeded in making a romantic movie in a very tough part of New York. Do you personally think New York in a romantic city?

DE NIRO: You could call it romantic. We always think Paris or some European city that is more beautiful architecturally is more romantic. New York is more exciting, I guess, than even Paris or London is, for the moment. New York’s the center of something; I don’t know what, really—the center of a lot of things. With all its problems and chaos and craziness, it’s still a great place to live. I can’t see myself living anywhere else.

SISCHY: Do you think you, Bobby De Niro, can get lost in New York?

DE NIRO: I can get around pretty easily. People don’t expect to see me walking around.

BRANT: You can be anonymous in New York.

DE NIRO: That’s the great thing about it. Of course, if you’re in a situation like we were for the photographs we did for this article, naturally you’re going to get recognized. But people are pretty relaxed and cool in New York.