New Again: Peter O’Toole

In his youth, Peter O’Toole was known for his baby blue eyes; striking good looks; and velvety, deep voice. But after cementing his talent as an actor in 1962 as the titular T.E. Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia, he went on to appear alongside iconic cinematic figures like Audrey Hepburn in How to Steal a Million and Katharine Hepburn and Anthony Hopkins in The Lion in Winter. He was a lover of the craft of acting, and continued to make films until he passed away at age 81 in 2013. In the weird and clever manner that was a signature of his personality, a few new films in which he appears have been released posthumously—the latest of which, the action-adventure movie Diamond Cartel, is his last, and out through video on demand this week.

To honor O’Toole’s legacy, today we revisit his quirky cover feature from our October 1972 issue, where he talks to actress and writer Joan Buck, a family friend, about visiting Andy Warhol’s Factory, philosophy, and escaping civilization. —Katrina Alonso

Peter O’Toole

By Joan Buck

Testy. Knows a lot about a lot of things, subjects so diverse as to flummox even the most accomplished phony catchers. Can’t catch him out. They’ve been trying for two weeks, the ladies and gentlemen of the New York press, to catch him out, to ask the question that will make Peter O’Toole lose his cool, his wit, and they can’t. Dick Cavett’s show, even that terrifying video show couldn’t faze him much. Although he sat in the green room at the studio writing Latin words on his wrist and being nervous, with his wife Sian trying to send out calming vibrations, thinking he couldn’t do it, he did it. And a very good show it was too, despite the beeps.

Then there was the Judith Crist Weekend at Tarrytown, a conference center used to make mini-film festivals for people who wouldn’t otherwise end up in Cannes, Venice, or Cartagena at the right time. Handled it beautifully. Mrs. Crist is a very intelligent lady, and he liked that, answered questions from a roomful of movie buffs, proper answers, not fielding them as famous people are wont to do when they don’t feel like exercising their grey matter for the sake of a bit of publicity.

And parties, dinners, and interviews, interviews, interviews. And me one of the interviews. Odd that, really. I’ve known him 13 years, he used to put me in garbage cans. My father is his partner. I see Peter and Sian often enough in London, I even see them in Ireland. Why I of all people had to be fitted in with gentlemen from Newsday and god knows what, in this tight schedule, was a mystery. Perhaps to give him a bit of respite, or to lay me on the line. Performing families are like that. “Come on kid, do your dance, sing your song, since that’s what we hear you can do.” Take out your little tape and get together something for Interview.

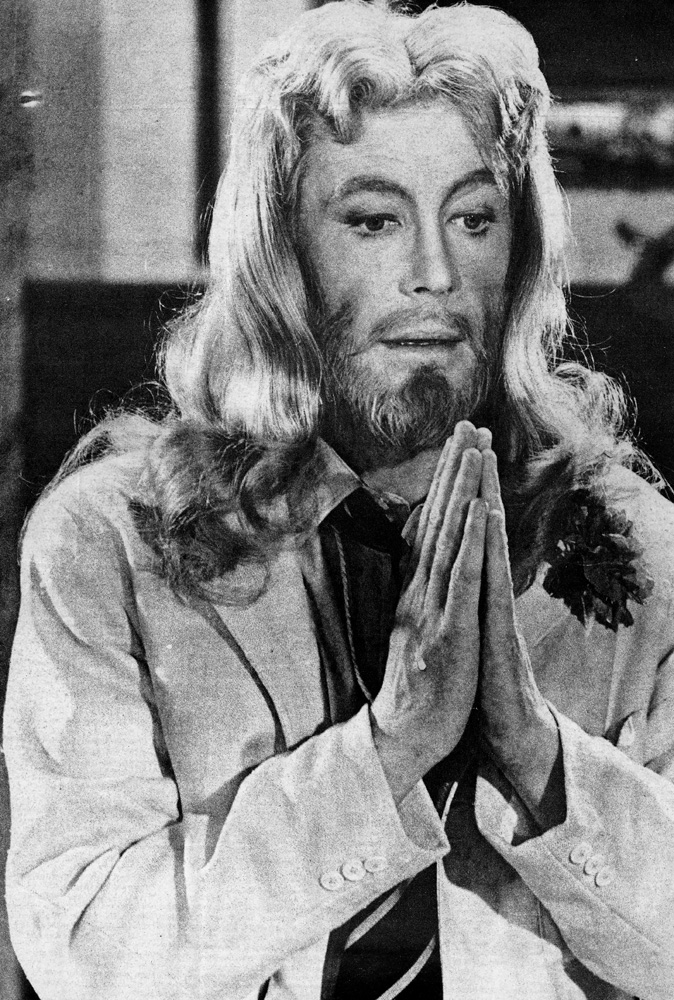

What Peter O’Toole represents for most people is, I suppose, a cross between Lawrence of Arabia and King Henry II. What better fantasy figure could the fags of the world have to pin in their minds than Lawrence in his long white dress marching across a train (take that a level further and get the symbolism of trains in films and you’ve really got a fantasy) Henry II appealed less to those concerned with form, but those performances had fire, man, fire. Now he is [on] posters jumping off a crucifix, and he is bloody brilliant in The Ruling Class. He is less aware than anyone I have ever interviewed of what his public persona is, but then it is much easier to pin down a stranger’s personality with a couple of hundred words than it is to write about someone you have seen change over the years. That’s why they print biographies in hardcover. Maybe it’s just a symptom of reverential awe, but probing and messing about with people’s words, histories, likes, and dislikes seems futile. He is a great stage actor, a “fillum” star, an erratic, quirky, creative man, an uncle figure who is younger than my last boyfriend, and a very clever man. I shall never cease to be grateful for his advice, delivered in a bar in Venice, counseling me not to live in the country with a young man I loved but who wanted to be a priest. “He just wants to have temptation so he can reject it,” he said, “don’t fo guckin’ about with tryin’ to be Lilith.”

He has certain things he keeps going back to. Age is one of them. He thinks of himself as about 180 years old. From which we get the testiness, the “I know it already” syndrome. And yet he is neither jaded nor blasé. When we did the picture at Berry Berenson’s, he was overjoyed at seeing a real New York pad, complete with guitar on the wall and plonk to drink. Fascinated by the Indian cultures of America, he engaged in a long discussion about the southwest, and commissioned Berry to find a peace pipe for a friend.

So here we all were in New York. The O’Toole suite belongs to a lady who really likes green, (the hotel is made up of private apartments) so there is a great deal of very bright green, and a painting of Venice on the wall which delights Peter because he loves Venice, a place he has known since 1946. His friends there are the gondolieri, the barman at the Danieli, the real Venetians who paint the old masters that hang in the chic Venetians’ palazzos. Sian is next door reading The Exorcist which we found in one of the rooms and have been passing around with intent to return it to the right room eventually. She has been reading all day. Peter has been talking to journalists all day, and a gentleman who has been supervising the interviews leaves when I arrive because I’m family and won’t misbehave. I wonder if he thought the other journalists would piss on the carpets, steal the booze, kidnap O’Toole, or borrow The Exorcist.

What kind of questions can you ask an old friend? When did you make Lawrence of Arabia? I know all that, how Peter went off in 1960 with dark hair and boundless enthusiasm, returning at times (blond) with camel saddles to demonstrate how you ride one of those beasts. Sending telegrams suggesting a film with a “Nice Nubile Lady,” because he was sick of Arabs and camels. I know, so does everyone, that he was born in Ireland 40 Augusts ago, grew up in Leeds, worked for the Yorkshire Post, went to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, spent two years at the Bristol Old Vic, went up to Stratford, made The Day They Robbed the Bank of England and then Lawrence, then the other films, Beckett, Lord Jim, What’s New Pussycat, Night of the Generals, Lion in Winter, Goodbye Mr. Chips, Country Dance, How to Steal a Million, etc. For the public, the actor became a movie star, but Peter is not a movie star. Too intelligent, too funky, too curious. Accepting one’s glory is not a failing of people like O’Toole.

PETER O’TOOLE: I’d like to be with your mob rather than the others. You all go to exciting places called the Factory or something.

JOAN BUCK: Do you want to come down to the Factory?

O’TOOLE: Where is the Factory?

BUCK: Union Square.

O’TOOLE: Where’s Union Square?

BUCK: Twentieth Street.

O’TOOLE: We won’t have time today.

BUCK: Let’s go down Friday. Now, Mr. O’Toole…

O’TOOLE: Yes sir!

BUCK: Tell me about your new picture The Ruling Class.

O’TOOLE: Go fuck yourself!

BUCK: [general hilarity] Why do you always do films that are either historical characters or plays?

O’TOOLE: Yes it’s true, I usually do films that are literate and literate authors use history as a source. It is true. If you look at any film I have made from Lawrence of Arabia on down, Robert Bolt is a playwright, Harry Kurnitz was a playwright, Goldman is a playwright, Anouilh is a playwright, Peter Barnes is a playwright. Yes. Of course.

BUCK: Does that mean you’d rather be on stage?

O’TOOLE: No, it means I’d rather work with good authors. I’m an author advocate, I always have been. I’m not Rin Tin Tin-Nice lamb chop, woof woof. When I come unstuck it’s because I’ve not had an author.

BUCK: What would you consider coming unstuck?

O’TOOLE: Well I’ve come unstuck a few times haven’t I? Lord Jim. Night of the Generals. There was no author as such.

BUCK: Who did the script?

O’TOOLE: Oh 27 people all writing in committee. I think that the cinema is an extension of the drama, one of its facets, and the drama as far as I’m concerned is authors. Well I’m not a mime, a mimist. All you need is an author, an actor and an audience. That’s the drama. Bare boards and a passion that’s the beginning of it all.

BUCK: What about the director?

O’TOOLE: In the cinema it’s different. In the theater you can chain a blue-assed baboon in the stalls and with a good script, good actors, and a good set you’d have what is called a production. With the cinema someone has to know about lenses and fine things. I have no time for the “auteur de cinema.” To me, it’s meaningless.

BUCK: Why?

O’TOOLE: Well what does it mean?

BUCK: A man who creates something in the image of what’s going on inside his head and uses actors and movie cameras for it.

O’TOOLE: Well, I’ve no time for them, none at all. I can only function in the literate drama.

BUCK: What was the first play you ever saw.

O’TOOLE: A musical called Rosemarie. Oh Rosemarie I love you. I was six.

BUCK: Did you want to become an actor then?

O’TOOLE: I fell in love with Hardboiled Herman. He’s a baddie.

BUCK: And you started off playing character parts?

O’TOOLE: I started off playing juveniles, oddly enough. The name “character parts” is totally meaningless. The French put it better: acteur, comedien. I’m a comedien. It doesn’t mean I think I am the character I’m playing; it means I think that character is me. I take it over. I pretend that Henry II is me. The Earl of Gurney is me.

BUCK: But the characters that you’ve played are all so different.

O’TOOLE: I can tame multitudes. I can’t tell you about acting. You can develop all the skills, voice, gesture, movement, you can develop by exercise and practice but finally fundamentally it’s mining from yourself, from your own personality, from what you know. If you can’t know it you can have a good guess by people you know or books you’ve read. I couldn’t have played Shylock the way I did if there hadn’t been an Auschwitz. I played it with one foot firmly in Auschwitz. Shakespeare had a consciousness of what had happened to the Jews. Merchant of Venice was written after the trial of Lopez, one of the great anti-Semitic trials of all time in Portugal. And the courage that it took—you see Christopher Marlowe was playing very safe with his Jew of Malta, nice big comedy. Shakespeare looked as if he was playing safe by having Shylock say he didn’t like Christians. That’s his first speech. After that watch the irony. The Christians look such idiots. Bassanio’s first words: “In Belmont there is a lady richly left and she is fair.” He’s got his priorities in the right bloody place, hasn’t he? The first show I was ever in was The Scarlet Pimpernel. Marius Goring. I played his aide-de-camp. Chaubertin, the man who chases him. I was at [Royal Academy of Dramatic Art] I had to say—what’s that bird: “A sea mune citizen” and he said, “shoot it” and I said, “It’s night, citizen,” then I had to chase somebody on a horse. I mean I was on the horse. Filled it with sugar drops. It was rattling with them. I had to chase after this coach. Lost an iron, swallowed a fly, lost a wig, and said, “You are to make the acquaintance of Madame Guillotine.” End of part. But you know I did lots of stunts when I was at RADA., under all sorts of names. Walter Plings, Charlie Staircase, Arnold Hearthrug. The first proper thing was called “Once a Horse Player” which was for television. Then a thing I wrote myself called “End of a Good Man.” A little Sean O’Faolain story. Then I played a journalist on an airplane with Patricia Neal. Then I made that awful Kidnapped. There was a part in it, Rob Roy’s son, who challenges Peter Finch to a duel and they settle for bagpipes. Finch said there’s only one fuckin’ actor I know who plays the bagpipes and that was me.

BUCK: Where did you learn to play the bagpipes?

O’TOOLE: When I was a boy. I played with a thing called Lord Kolmorry’s Own Hibernians. In Leeds, in France, in Ireland, all over the place. I was a piper with an Irish piping and dancing group.

BUCK: Didn’t you play Gaudier Breszka? [The subject of Ken Russell’s new film Savage Messiah.]

O’TOOLE: That was nearly the last television I ever did. There was an old beat up play which we wrote. I called it The Laughing Torso, they changed its name to The Laughing Woman. That was after the Bristol Old Vic. I can’t remember.

BUCK: Tell me about when you were a journalist. What did you do?

O’TOOLE: Made tea. Got tickets for theaters, football matches.

BUCK: Didn’t you write?

O’TOOLE: Oh, yes. “The bride wore nine thousand yards of pink tulle.” Rubbish. “The Stars and Miss Gertie Dillon” was one heading of mine. Death of an old boarding house keeper called Gertie Dillon. All the stars had stayed with her. She had two wooden legs.

BUCK: Tell me about the Eskimo film.

O’TOOLE: Oh Christ. I’d forgotten about that. It was the funniest thing I’ve ever been in. There was a small part in this story about an Eskimo for an Irish Canadian mounted policeman who goes to arrest this Eskimo, the Eskimo saves his life and insists that he sleep with his wife. He gets to adore the Eskimo and his wife, but the Eskimo must turn himself in. The Eskimo insists on being arrested and the only way he can get rid of the Eskimo is by kicking him in the face. That’s how it started off but they changed it every day and I suddenly turned out to be French Canadian; there was a marvelous moment where they rewrote so much they got stuck. They’d got huskies and polar bears and all sorts of things and they didn’t know how to get this sledge made. So I suggested the Eskimo should eat me, that would have given him nourishment, then make a sledge out of my bones and skin. They said we want a happy ending and I said “Couldn’t he whistle.”

BUCK: Where did you shoot it?

O’TOOLE: In the studio in salt. Piles and piles of salt with trained seals, performing seals who wouldn’t perform, being fed fish. Two polar bears imported from Dublin and they didn’t look white enough, so they coated them with peroxide and they went mad.

BUCK: And then you made…

O’TOOLE: The Day They Robbed the Bank of England with a gentleman called Jules Buck. He wanted me to play the tearaway Irishman, but I asked if I could play the guards officer which was a lesser role, and he said yes. He had been my partner ever since.

[At this we dissolve into winks, the public and the private life coming together like two plastic lenses, me stuttering and floundering in the no man’s land between knowing the facts and not knowing the feelings.]

BUCK: The first time I met you you were introduced as Peter Autoul and I thought you were French.

O’TOOLE: Autoul. Of course. Oddly enough there is a French family called D’autoul. They wear the little lion crest, part of the wild geese who fled in the 18th Century and were awarded bits of land by Napoleon. Very posh.

BUCK: What part did you most enjoy?

O’TOOLE: I most enjoyed playing Henry II.

BUCK: Which is why you played him twice?

O’TOOLE: There’s plenty of evidence to make a third. Tennyson’s written one. Christopher Fry’s written one.

BUCK: Why haven’t you written a play?

O’TOOLE: Most difficult thing in the world, to write a play. Do you know the story of Shaw at the Fabian society? H.G. Welles said I’m terribly sorry I’ve missed the last five meetings, I’ve been terribly busy, I’m engaged in writing a scientific pamphlet on the effects of radioactivity in 1984 and I’ve produced a novel, and various pieces of science fiction to do, and I’ve had a bit of personal trouble, and I had my copy to bring out for the newspaper.” Shaw leapt up and said, “I’ve not missed one meeting, and I have written a play!” hardest thing in the world. If it were easy they’d all be at it.

BUCK: Do you ever wish for a part that would be everything?

O’TOOLE: Well, I’ve had that, Joanie, I’ve played Shakespeare you see even his minor parts have that. He’s the best.

BUCK: Is there anybody now?

O’TOOLE: There’s great hopes for everybody—Robert Bolt, Peter Barnes, John Osborne; Shakespeare is the best. You talk about auteur de cinema having things in their heads and putting them all across, can you imagine Shakespeare writing screenplays?

BUCK: Don’t you need that whole context of an ordered world, or at least where you know the order should be, where the head of the state is the King, there’s the church, inheritance and bastardy, people killed one by one in wars, to unite plays?

O’TOOLE: I think that Shakespeare used archetypal characters. He merely used them for a framework for what he wanted to talk about which was mankind, the human condition. I think Beckett comes close to Shakespeare, Sam Beckett. And he doesn’t need kings or monarchs. I don’t think Shakespeare needs them. His finest work happens to be about a king. I was asked once when I was playing Hamlet, “Would I walk more like a prince?” I said, which prince do you mean? Prince Littler? Prince Monolulu? Hal Prince? He calls them princes or cardinals, but he just writes plays about people. There are enough princes and cardinals around now.

BUCK: Why isn’t anybody writing about them?

O’TOOLE: Peter Barnes is.

BUCK: Well The Ruling Class seems extremely Shakespearean.

O’TOOLE: I would put it nearer Ben Jonson, as a playwright. Foibles, follies, crimes.

BUCK: Like the Duchess of Malfi? Do you have any real feelings for films? Do you like to go see them?

O’TOOLE: Less and less as it gets less and less literate, and I don’t mean it has to be wordy. The images aren’t even composed with any sense of style. I’m no great cinema fan, no. I love a good film.

BUCK: What’s a good film?

O’TOOLE: On the Waterfront, The Seven Samurai—the American Shakespeare, the smashing Julius Caesar. My favorite filmmaker is Kurosawa. To me he’s the perfect blend of the image and the word. Superb. I’d love to do King Lear with him.

BUCK: I thought he was very ill?

O’TOOLE: Hmmm?

BUCK: Syphilis.

O’TOOLE: Syphilis did you say? Good Lord how very interesting. What a marvelous death. Perfect for Lear. The great theory is that Shakespeare wrote it when he was poxed to the nines. What’s the line—”A convocation of politic worms are active.” They seem to have found evidence there. The great misanthropic plays, Lear, Timon of Athens, all have images of pox, dark, devils down below…

[A bell rings. It’s only food—carry on.]

Fuckin’ marvelous, isn’t it, making a film whose image is all down below, there’s devils, there’s darkness, “Copulation thrives and the fly goes to it,” made by a syphilitic? I suppose I’d have to make my contribution and get the clap or something, or a token crab. [pause] Do go on.

BUCK: Yes sir, you, intimidate me.

O’TOOLE: I mentioned it to him a long time ago and he nodded. But finally Kurosawa’s such a rooted man either I would have to learn Japanese or he would have to learn English.

BUCK: What would you like to be doing in New York?

O’TOOLE: Seeing friends, going to the theater.

BUCK: I saw that play last night that Phil Bruns told us about.

O’TOOLE: Is it good?

BUCK: I didn’t like it. So ’50s.

O’TOOLE: I don’t mind that if it’s good ’50s. I’d like to see Tennessee Williams in Small Craft Warnings. I’d like to go to the Factory. I saw Peter Glenville this morning. He’s thinking of doing a Tennessee Williams.

BUCK: Tennessee Williams has really picked up again.

O’TOOLE: Thank god. He’s another one. Probably the finest playwright of my generation in the English tongue. Then there’s Anouilh…

BUCK: Giradoux?

O’TOOLE: Yeah, but Giradoux doesn’t translate well into the English language. D’you know I’ve had about five flops of Giraudoux—Ondine, Sodom and Gomorrah, I did at least three on the trot which died the death.

BUCK: What about Tom Stoppard.

O’TOOLE: Tommick Straussler is his name.

BUCK: That’s what I wanted to know.

O’TOOLE: He was a young journalist in Bristol when I was a young actor. He’s another one—we haven’t seen anything of Stoppard yet. There’s a lot more to come. He’s no nine-day wonder. Ninety-nine percent of the stuff today is nine-day wonder, trivia pushed out as something that it isn’t. There are far too many theaters, far too many cinemas.

BUCK: Do you see yourself getting better and better?

O’TOOLE: I did until about two, two and a half years ago.

BUCK: What happened?

O’TOOLE: I reached a point where it didn’t all come together. Technically I’d raced ahead in some bits and mentally I’d raced ahead in others and they hadn’t come together. I’ve done too much. I’ve exhausted myself. Temporarily I’ve reached my limit, time I did something else. I’m a great believer in diversity as you probably know. I can still turn up and mum, I can turn in good professional performances, but I’m not interested in that, I’m interested in being absolutely stretched and totally committed. I’m just fed up that’s all. I need a very great change.

BUCK: What?

O’TOOLE: Scribble a bit, archaeology a bit, maybe just go down to sewer at my house and make the pipes in order, build a pump house.

BUCK: You know in Jung, there’s a classification of different types: there’s thinking, feeling, instinctive, sensation, as an actor you’re instinctive and…

O’TOOLE: What a load of crap!

BUCK: Eh?

O’TOOLE: Freud has done so much damage—and his disciples.

BUCK: It’s not Freud, it’s Jung.

O’TOOLE: I said “and his disciples,” what an absolute total blinkered lot of rubbish. The moment you start dividing thought and feeling, the ratio of sinitive from the intuitive, you’re dead. There is no difference between emotion and thought. You can be unreasonable. This bogus classification, this chopping up of the body. It’s only a 19th-century notion anyway, never occurred before. It’s Jesuitical crap. The soul and the body, it is one total thing. Look at how the root of feelings changed so much. Used to be the heart didn’t it? That’s stopped now, that’s a pump. Elizabethans had it the bowels, then it was the stomach in the 18th century, now they’ve got everything tidied up and explicable. God, Jesus there are only two things one has to bear in mind. One has to be credulous—able to believe—and skeptical—able to not believe, because if you are not skeptical, you will believe rubbish. If you are not credulous you will learn nothing and the only way to balance those two is to recognize the mystery of things.

BUCK: And open it up?

O’TOOLE: Open it up, revere it, do anything you want, but know it, that’s all there is the rest is dross.

BUCK: Knowledge, lots of knowledge, lots of self knowledge, lots of experience—trust experience—god even if it leads you in crackpot ways it’s better to have experienced it. I’m so sick of people being told what to do, what to wear, how to feel, what to think. People want that.

O’TOOLE: People shouldn’t want that. If man ever comes to perfect equilibrium with the environment, we’ll all be redundant, perhaps because you won’t need art or letters.

BUCK: Are they a reaction against the impossibility of everything?

O’TOOLE: Don’t explain it. They’re artists they’re doing something, taking a hunk of chaps, giving it some order, some form, and presenting it saying here is my little song and dance, my chaos.

BUCK: So many people who’ve seen you have been given a model by you.

O’TOOLE: You’re contradicting yourself; you just said what different characters I’ve played.

BUCK: Lawrence and Henry II are two different things but both strange. In Lawrence the amazing fantastic young prince—in Henry the powerful patriarch.

O’TOOLE: You mean I’ve confused people?

BUCK: I think anything an artist does confuses people.

O’TOOLE: No, no, no anything an artist does is to show ourselves as we really are, which is a complex thing. I don’t think that one work of Philosophy or Art, or Letters, or Acting, or Middle Playing, or Tightrope Walking, or Flea Circuses has made mankind better, if by better you mean kinder, wiser, more tolerant of each other. One thing self knowledge. Knoticayton: know thyself.

BUCK: Do you consider that you’ve learned more through the parts you’ve played or the life you’ve led?

O’TOOLE: They’re inextricable. Certainly the parts are great … if I’m Henry II, I read everything I can on Henry II, that leads me from history into the law—to think that the jury system we have is Henry’s invention can lead me to a bit archaeology to find his roots at Chinon. That leads me to even the wines in the district.

BUCK: Everything opens up continually. Could you have lived another life?

O’TOOLE: I don’t think about that because I’m not very good at hypothesis. I didn’t become anything other than an actor so it never occurred to me that I could.

BUCK: That’s vocation.

O’TOOLE: Is it?

BUCK: Well, it’s very difficult because you don’t like words being given for things, but don’t you ever … watch yourself?

O’TOOLE: Stand “outside myself watching myself watching myself?” Too much. One of the reasons I’ve got … do you mean that physically?

BUCK: Yep. Standing outside seeing where you are, wondering—

O’TOOLE: Yes. We’re on the same track. I find that so self conscious as opposed to self knowing. Don’t like that. That’s why I’m stopping.

Last time I saw them was in Ireland. I arrived at their house, built on a promontory to catch a view of the sea all round, the Aran Islands, and every passing gale, in a bicycling rain. The drains had broken. The pipes had been crushed by rocks. A couple of Irish workers were out there with a big machine, and one of them was teaching Peter how to divine water with a rod. He took it in his hands, palms upwards, and the sensitive hazel twit described a full circle, almost immolating him in the process of indicating water. Then it turned out that his daughter Kate, his mother in Paw Mungee, myself and the nanny could do it too. Sian, though she is a druid, can’t. Nor can Pat, the younger daughter. Later we were taught another way of finding water; you take three eggs, hold the bottom one in your left hand and the top one in your right hand, and if water is lurcking anywhere underground, the egg in the middle will spin so fast you’d swear it was magic. Which it is. And Peter O’Toole is very good at that too.

That evening, as the mist had settled in no uncertain way over the only road that leads to the house, we prepared dinner. Suddenly the girls, outside on their bicycles, started screaming that three people were coming up the drive. We peered in the hostile manner reserved for trespassers, and after much conjecture realized that the lady in the middle, the one in the car-coat lining, white turtleneck, black trousers, and black cap with a scarf underneath it was Katharine Hepburn. “We were just driving by and thought we’d drop in” she said in a voice I associate with Calla Lilies. And the wind rattling all around the hand built walls, with the peat from the bog burning in the fireplace, Peter O’Toole began his retreat from the world. “Escaping from civilization?” inquired Miss Hepburn. “Hell no!” he replied, “This is civilization.”

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE OCTOBER 1972 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.