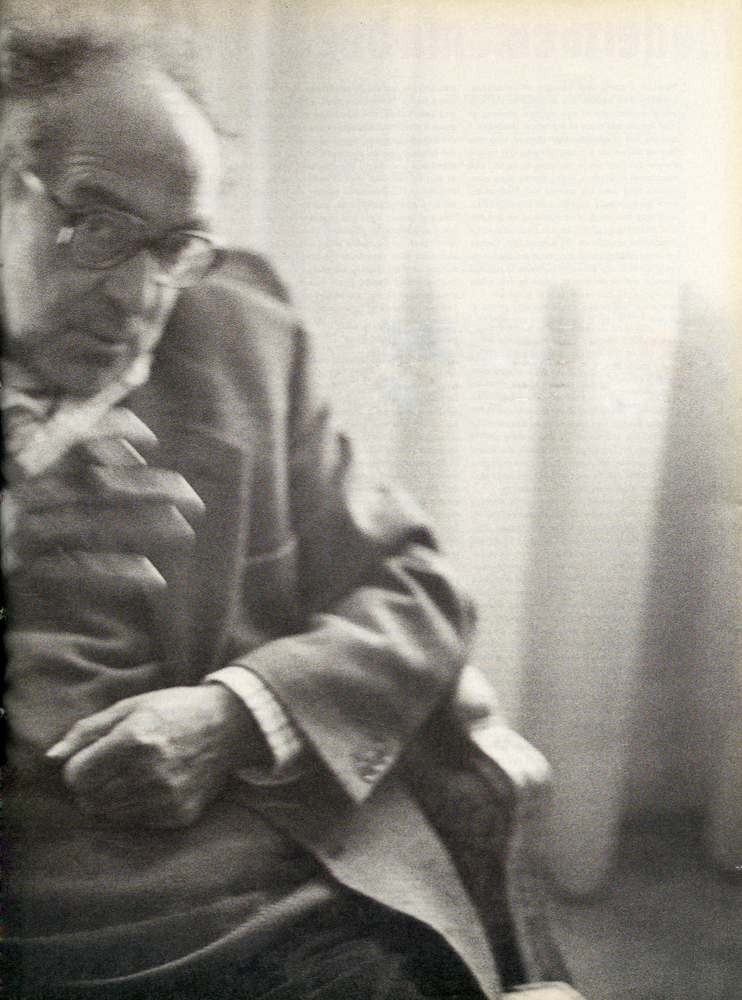

New Again: Jean-Luc Godard

Yesterday, we published an interview with actress Anna Karina, in honor of her appearance at BAM as well as the forthcoming series “Anna & Jean-Luc,” a survey of her work with French director Jean-Luc Godard that opens this friday at Film Forum in New York City. Just after we published the article, it was announced that a biopic of Godard’s life is being produced. Directed by Oscar-winner Michel Hazanavicius (The Artist), the film is set to star Louis Garrel and Stacy Martin. In light of the announcement and Film Forum’s upcoming events, here we reprint an article with Godard from July 1994.

Jean-Luc Goddard Now.

Modern cinema began with the enfant terrible of the French new wave. Andrew Sarris finds out what’s on Godard’s mind 35 years later.

Jean-Luc Godard, the paragon of paradoxes, has served for almost four decades as the analytical conscience of the modern cinema, at least for me and many of my fellow cineastes. I am only two years older than Godard, who was born on December 3, 1930 in Paris, but he has always seemed much younger in spirit, and much older in wisdom. Many people have complained that both his writing and filmmaking were maddingly cryptic and obscurantist. Aside from the marginal exception of his first feature, Breathless (1959), he has never enjoyed a commercial success on the screen. Still, Godard has been writing and filming for more than 40 years without any discernible break to lick his wounds, and he seemed as feisty as ever when I encountered him recently in a suite at Manhattan’s Essex House. I was there to do an interview, but for me it was more of a reunion between two friendly survivors of the ’60s.

Ah, the ’60s!—when cinema and politics both exploded with youthful fervor. In Breathless, Godard taunted Generalissimo De Gaulle by linking a shot of him following Eisenhower on the Champs-Elysées to a shot of Jean-Paul Belmondo chasing Jean Seberg along the sidewalk. This mocking linkage was never seen by American audiences, but technically it was worthy of the Einstein of Ten Days That Shook the World (1928). Just try to imagine Einstein satirizing Stalin instead of Kerensky, and you get some idea of Godard’s curiously apolitical audacity.

Godard’s second film, The Little Soldier (1960), described some of the intrigues of the Algerian War without resolving the issues. The story is told from the point of view of an uncommitted intellectual, who in many ways resembles Godard. The film was completely suppressed for two years. When you added provincial and international indignation over Godard’s penchant for gratuitous nudity, recurring controversies with other critics and filmmakers, and wildly varying reactions from audience, ranging from wet-eyed enthusiasms to enraged indifference, it seemed Godard was a walking scandale, eternally embattled, trapped between the steady crossfire of his defenders and his detractors.

I began waiting for Godard back in 1961 on my first extended visit to Paris. I tried to interview him at about the same time I interviewed the late François Truffaut, but somehow we missed connections. He reached his zenith with me and my fellow Godarians with Pierrot le Fou (1965) and Masculine Feminine (1966). Throughout the late ’60s, Richard Roud, the director of the New York Film Festival, took a great deal of heat from disgruntled New Yorkers over the steady diet of Godard movies he fed them.

Although Godard always admired American movies as a critic, he never practiced their pragmatic virtues as a filmmaker. He was always much closer to Rossellini, for example, than to Hitchcock. Like Renoir, Godard always sacrificed form to truth. Godard’s career was undeniably shaped to some extent by necessity. If he had the choice, he would have preferred to make lavish Technicolor films with Kim Novak and Tony Curtis, two pop icons he understood much better than did his American middlebrow detractors. But dire economies and commercial failure drove him eventually into the abyss of television and video. Nonetheless, every foot of film he has ever shot is defined by the extraordinary treatment of reality as a volatile mixture of the subjective and the objective, fact and fiction, logic and improbability, plausibility and actuality. Godard’s characters often read “real” newspapers aloud on the screen, and what they read from the uninflected journalism of their time is infinitely more bizarre than anything Godard could invent. Truth was stranger than fiction, and history was hysterical. This was Godard’s narrative aesthetic, and he accepted full responsibility for it. He never said that this was life but that it was life as filtered through the camera. This acceptance of responsibility was the ultimate source of Godard’s personal brand of realism. By standing between us and his characters, Godard forced us once and for all to accept the director as a creative force. For those of us who made an aesthetic principle out of the fact that movies did not materialize miraculously on the screen, Godard became the foremost realist of the modern cinema.

For the record, Godard was in New York to launch the world premiere of JLG by JLG, an autobiographical portrait of the director compelted earlier this year and produced by Gaumont. Also released this year was Hélas Pour Moi, a Godardian variation on the Amphytryon story, with Gérard Depardieu as the modernized wife-stealing Zeus.

ANDREW SARRIS: I’d like to tell you something Jean-Pierre Léaud told me a few years ago in an interview. The question I asked him was, “Who was the best director who ever directed you?” To his credit, he thought a long time—after all, François Truffaut had virtually invented Léaud as his alter ego, Antoine Doinel, in The 400 Blows, and followed him almost into middle age. Finally, he said, “Godard.” And that brings me to my first question. A recent book of Truffaut’s letters prints a very nasty exchange of correspondence between you and Truffaut in the ’70s. Yet, in an exchange with Serge Daney in your video series on the history of film, Historie(s) du Cinéma [1989–], you are very generous in your comments on Truffaut. Do you feel that way right now?

JEAN-LUC GODARD: Oh, yes. François deserved all the credit for making the necessary connections between the past and the present that made us the nouvelle vague. No one can deny him his rightful place in film history.

SARRIS: This leads to another question about your recent videotapes. Do you consider yourself inside or outside history, that is, both film history and general history? I notice, for example, your recent comments on Bosnia. Are you still out there on the barricades?

GODARD: Well, I can still be inside both kinds of history, but that doesn’t put me on the barricades. I write and film history; I don’t make it. One can be a good critic and a moral observer, but one remains professionally detached as a writer and a filmmaker. I didn’t have to pick up a rifle to make Les Carabiniers [1963].

SARRIS: Still, there was a period, say, in 1968, when you seemed to be much more active.

GODARD: Oh, yes, but we are all older and more tired.

SARRIS: I can’t argue with that. Today, do you consider yourself a Parisian or a resident of Switzerland?

GODARD: Neither. I’m Franco-Swiss. I’ve always been shuttling between these two worlds, never firmly planted in either one.

SARRIS: You were already talking about the women in Geneva and Lausanne in Breathless.

GODARD: Yes. I’ve always considered the French-speaking part of Switzerland as a province of France.

SARRIS: Where do you spend most of your time nowadays?

GODARD: I live mostly in Switzerland, but we still have an office in Paris, and I suppose we legally belong to France.

SARRIS: Do you vote in French elections?

GODARD: No, no, no. I manage to avoid voting in either country. I have no desire to vote for French politicians, and I’m not entitled to vote in Switzerland.

SARRIS: So you’re not in either political system?

GODARD: I am nowhere. You can call me the man in the middle.

SARRIS: Do you keep up with your old colleagues from Cahiers do Cinéma and the nouvelle vague?

GODARD: No.

SARRIS: No?

GODARD: Sometimes I talk to Jacques Rivette.

SARRIS: What do you think of your surviving colleagues, like Claude Chabrol and Eric Rohmer?

GODARD: I appreciate them all… Not all of them, but some of them. And I think if they come up with two or three good movies in 20 years, it’s an enormous achievement.

SARRIS: Do you see a lot of movies these days?

GODARD: No, we don’t go out that much.

SARRIS: You’re not near many theaters?

GODARD: Well, like Humphrey Bogart says, we’ll always have Paris.

SARRIS: When you say “we,” you mean you and your companion, Anne-Marie Mieville?

GODARD: Yes.

SARRIS: Do you have many videocassettes?

GODARD: Yes, but I don’t like to look at movies that way. I have a large number of cassettes, but I look at them mainly for reference purposes.

SARRIS: You still really love the idea of film on a large screen.

GODARD: Yes.

SARRIS: So you’re not part of the information super-highway?

GODARD: Just for information, about everu two or three years I like to see an old John Ford movie, and even on video you get some idea of what it was, but if you look too closely, you begin to miss the real thing.

SARRIS: Do you have a desire to get back into feature films more? I liked Nouvelle Vague [1990] very much.

GODARD: Yes, that came out very much the way I wanted.

SARRIS: But I must say I did not understand Hélas Pour Moi. I found it more difficult than Nouvelle Vague.

GODARD: It is more difficult. But there is a problem in pretending I can still control my destiny in the commercial market. This latest movie [Hélas Pour Moi] was made possible because I am still associated with a heroic period in French cinema, and my name remains linked to this period. So then a big star decides that he wants to take time off to make a “Godard” film.

SARRIS: You mean a star like Gérard Depardieu?

GODARD: Yes.

SARRIS: How did you get along with him?

GODARD: Not at all. He was supposed to work six weeks. He walked out after three. The extras did more acting than he did. But without him there would have been no money.

SARRIS: You made the same complaint about 30 years ago when you made Contempt [1963] with Brigitte Bardot.

GODARD: It was the same situation.

SARRIS: You have always preferred working with non-stars?

GODARD: Absolutely.

SARRIS: Pier Paola Pasolini delivered a paper at the Pesaro Film Festival about the cinema of poetry and the cinema of prose, and he say that you, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Bernardo Bertolucci made poetry, while John Ford and Ingmar Bergman were the old masters of prose.

GODARD: Yes, I remember Pasolini’s paper very well.

SARRIS: What I want to really ask is when you talk about Dostoyevsky in one breath and Nicholas ray’s Johnny Guitar in the next, are you talking more as poet or as an essayist?

GODARD: More as a poet, I would imagine.

SARRIS: Or when you talk about “the end of cinema” and “the end of art” and so forth, are these poetic statements or essayistic statement? Is art really disappearing, or are you simply losing interest in the art of today, the cinema of today? In other words, are you speaking in the first person or are you speaking for all of us?

GODARD: Well, in the first person, and pretending there is some truth in there for all of us. When Yeats said the center cannot hold, he was talking for himself, but it was true for the rest of us as well.

SARRIS: Why have you undertaken your Historie(s) du Cinéma?

GODARD: It’s a first step to cure people today of their dislike of history, and the fact that they can come out of a historical process, particularly in the cinema. Young people, especially in the cinema, don’t want to hear this. I’m very interested in tennis, but when I try to tell younger players about [Bill] Tilden, they’re not interested.

SARRIS: I noticed you walking around with your racket in Nouvelle Vague, and you looked like a real enthusiast. Someone told me that when you went to London recently to do some interviews, you were more interested in Wimbledon. You are involved in tennis?

GODARD: Very much, yes.

SARRIS: I’ve always noticed in your films that you’ve emphasized the physicality of life, what people do with their bodies.

GODARD: Cinema is movement, after all.

SARRIS: But I’m thinking of something more extreme, like in Hail, Mary [1985] where you have these Amazon women playing contact sports. Those strenuous images seem to fascinate you. Is that part of your sense of what cinema is about?

GODARD: Yes, it teaches us about the human body and how we look at things. Cinema is not a series of abstract ideas, but rather the phrasing of moments.

SARRIS: What are your politics right now—that is, do you have any politics?

GODARD: Only what you see on the screen.

SARRIS: You were considered a Marxist activist at one time.

GODARD: Oh, no.

SARRIS: You were never a Marxist?

GODARD: I never read Marx.

SARRIS: But you talked about Marx.

GODARD: Yes, but only as a provocation, mixing Mao and Coca-Cola and so forth [in Made in the USA, 1966].

SARRIS: How you like to be remembered?

GODARD: I haven’t started thinking about that.

SARRIS: Which of your films are you most proud of?

GODARD: No films in particular. I don’t think I’ve succeeded in making any really good films. There are moments, scenes, whole movements that sing. It has all added up to a cinema of sorts, even though I’m still learning my art.

SARRIS: You’ve never been overly concerned about commercial or popular success.

GODARD: Not too much. I’m satisfied to have an ordinary success and an ordinary life and an ordinary income. Later, I don’t know. But through most of my career I’ve made a decent living making movies no one wants to see. The average income in France is $1,000 a month, and you can’t live decently on that. I can afford to pay my own way to the Concorde, but Gaumont picked up the tab this time.

SARRIS: I’ve always wondered how you hit upon the electrifying jump cuts in Breathless. Was it instinct?

GODARD: Yes, partly. But the fact is that, unless you are very good, most first movies are too long, and you lose your rhythm and your audience over two or three hours. In fact, the first cut of Breathless was two and a half hours and the producer said, “You have to cut out one hour.” We decided to do it mathematically. We cut three seconds here, three here, three here, three here, and later I found out I wasn’t the first director to do that. The same process was described in the memoir of Robert Parrish, who was an editor on Robert Rossen’s All the King’s Men [1949]—he was the third or fourth editor, actually, because his predecessors weren’t capable of making the cuts. Parris told Rossen: “Let’s do something different. We’ll look at each shot and we’ll keep only what we think has more energy. If it’s at the end of the shot, we’ll throw out the beginning. If it’s at the beginning, we’ll throw out the end.” That’s exactly what I did later, without knowing what they had done. Only, I said, “Let’s keep only what I like.”

SARRIS: The other thing that was very new and fresh when you started was suddenly shooting in the streets with [cinematographer] Raoul Coutard’s hidden camera, capturing the fresh faces of Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo.

GODARD: many of us couldn’t afford to work in a studio, so our movies were not something we had planned in advance. In my case, it was my natura way of doing things. I mean, more or less I am always saying, “Give me more. Let’s do what has not been done.”

SARRIS: To this day.

GODARD: To this day.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JULY 1994 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.