New Again: Jane Campion

When Amour, Michael Haneke’s film about an aging couple struggling after a physical setback, won the Palme d’Or earlier this week, the 70-year-old Austrian director became one of just a handful of directors to win the Cannes Film Festival’s top prize two times—and the only person ever to do so within the span of only three years (he also won the prize in 2009 for WWI drama The White Ribbon). The award sets high expectations for the drama’s US release in December, especially considering past winners of the prize have included such classics as La Dolce Vita, Les parapluies de Cherbourg, Taxi Driver, Pulp Fiction, and The Piano.

Back in January 1992, Interview spoke with Jane Campion in anticipation of The Piano, the film for which Campion received the Palme d’Or in 1993. The Piano, which in early 1992 was tentatively titled The Piano Lesson, went on to win three Academy Awards in 1994, including one for Campion’s screenplay and another for the acting of a young Anna Paquin—who preceded her True Blood career by being the second-youngest Oscar winner in history (Tatum O’Neal has her by a solid year). In the interview, reprinted below, the filmmaker talks about her controversial portrayal of females that would go on to typify her success.

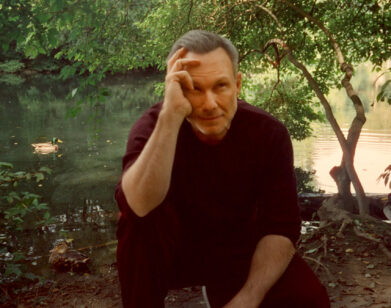

Jane Campion by Katherine Dieckmann

Jane Campion directs horrific, funny, and wildly expressive movies about misunderstood women, family abuse, and the way overripe imaginations transform banal reality. It’s a sign of how deeply Campion’s films probe the recesses of the psyche that people automatically presume her to be a dark cloud. Instead, talking on the phone from Sydney, the self-professed “chatty and social” Campion is crisp, quick, and prone to bursts of hearty laughter.

She first attracted attention for Sweetie (1989), an unsparing look at a bland, repressed woman, her id-driven sister, and their parents’ sheer inertia. Campion’s willingness to depict blood, piss, and anguish through a violently tilted camera won her mostly praise, with a few nervous dissents. Last year’s An Angel at My Table, adapted from Janet Frame’s autobiographies, served up a more becalmed but no less compelling look at the shy writer’s struggle to define her creativity.

A third feature, tentatively titled The Piano Lesson, is currently in pre-production. Set in Campion’s native New Zealand, the 19th-century period piece explores a love triangle between a mute pianist (Holly Hunter), her greedy homesteader husband (Sam Neill), and a dashing ruffian (Harvey Keitel). Campion says the film is inspired by Gothic Romantic writing, partially takes place in the “delicate and exotic bush, which can be very claustrophobic and frightening,” touches on the forced assimilation of the Maori people, and “tries to explore the relationship between fetishism and love.” A promising combination, to say the least.

KATHERINE DIECKMANN: An Angel at My Table was shot in a much simpler style than Sweetie and the three shorts you made at film school [Peel, Passionless Moments, and A Girl’s Own Story], with far less interest in extreme angles and framing. Will The Piano Lesson take you back in that direction?

JANE CAMPION: I’ve been wondering about that very much myself! [laughs] Actually, I’m finding myself less and less interested in what you can do with shots and things. There’s probably only about twenty different possibilities in the end. I’m more after what sorts of sensations and feelings and subtleties you can get through your story and can bring out through performances—although at the same time, I’m always wondering about style, trying things out. I do a lot of drawings for my films. The Piano Lesson is very sophisticated, easily the most adult or complex material I’ve attempted. It’s the first film I’ve written that has a proper story, and it was a big struggle for me to write. It meant I had to admit the power of narrative. And there is definitely room to play, visually—in fact, there’s a big call for it.

DIECKMANN: But even when you shoot a scene that could be considered relatively straightforward, you always have several things going on apart from the main situation. Your films are dense that way.

CAMPION: I can’t imagine the world being anything less than that.

DIECKMANN: Right, but most filmmakers can’t quite swing it.

CAMPION: That’s just how I see things on a base level: there’s so much going on. Or at least I like to have that feeling. It’s part of being interested in notions of reality apart from storytelling. I don’t know if it has something to do with having an art school education, which makes you aware of the way visuals speak, or makes you trust them more.

DIECKMANN: You used to be a painter, right?

CAMPION: Yeah, well, sort of! [laughs] I never did anything very good! There was a big drive when I was at art school to make you aware of the economy of meaning—after all, this was still during the tail end of minimalism. Being responsible for everything you put in your picture, and being able to defend it. Keeping everything clear around you so you know what is operating. To open the wound and keep it clean. [laughs]

DIECKMANN: When An Angel at My Table came out, a number of male critics complained that the protagonist was so gloomy, that she never lightened up, and that they couldn’t really enjoy the film.

CAMPION: I know that the critical response in America was highly mixed and not great. But here and in Europe the reception was very good, from both men and women. I just feel sad that those men had that impression, because they must have a tragically dull vision of what it means to be female.

DIECKMANN: Isn’t it beyond dull?

CAMPION: I just feel like they didn’t get it, and I probably wouldn’t get them, either! Maybe there’s less femininity in American men. Or maybe they just don’t like dumpy redheads. [laughs] Or, more basically, those men probably find women very threatening and difficult, unless they’re packaged like sex objects.

DIECKMANN: As much as you’ve shown how men often don’t understand women, you’ve also exposed how cruel women can be to each other.

CAMPION: To me, that cruelty is just a human instinct. It’s part of what I recognize to be true, without damning it or taking a moral position on it.

DIECKMANN: Yes, but within certain strains of feminism there’s some desire to present a united front.

CAMPION: I don’t belong to any clubs, and I dislike club mentality of any kind, even feminism—although I do relate to the purpose and point of feminism. More in the work of older feminists, really, like Germaine Greer. I remember when she came and spoke to us at university and told all the boys to leave the audience. [laughs] That was really an exciting feeling—sort of like watching Thelma and Louise blow up the petrol truck.

DIECKMANN: Did you envision yourself having a creative life when you were young?

CAMPION: No, I just thought, in the most unconscious fashion, that women don’t have those sorts of careers, and if you’re a talented woman you support a talented man.

DIECKMANN: What transformed you?

CAMPION: I did this Super-8 film at art school called Tissues, this black comedy about a family whose father has been arrested for child molestation. I was absolutely thrilled by every inch of it, and would throw my projector in the back of my car and show it to anybody who would watch it. Then one day someone said to me, “You don’t have any wide shots in the film.” And I said, “Wide shots? What are they?” That comment kind of blew my whole world apart, and I realized that I did not have any idea of what I was up to. So over the next few years I went on a very self-conscious quest to understand film language. I also looked at lots of still photographs, for compositional interest and, you know, to take in what a vision was. You can see that influence, since I don’t move the camera all that much.

DIECKMANN: The success of Twin Peaks created this movement in mainstream culture of what I can only call behavioral quirkiness. Your films depend on that strangeness to illuminate human situations. How do you feel about its broader applications?

CAMPION: I think two things. One is very practical, like, “Ew, does that mean I have to come up with something new?” And the other is “Oh, isn’t that great that, even in a superficial way, there’s this little celebration of individuality?” I feel kind of excited about that. My instinct is that it all comes down to meaning, and you return to films where there’s some sort of tight emotional rationale. Those films don’t seem to age; they seem like the beginning of everything. And I suppose this phase of eccentricity will disappear, since there seems to be a high turnover for new things. But my most obvious, on-the-top, surface-y response? Well, I just won’t be doing that anymore, then!

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE JANUARY 1992 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again click here.