New Again: Giancarlo Giannini

On Monday, the yet-to-be-released Italian film Shades of Truth was screened near the Vatican. It was met with universal criticism. The film attempts to defend wartime Pope Pius XII against the accusations of him turning a blind eye to the Holocaust, although according to multiple sources, it falls short. While it is based on more than 100,000 pages of documents and testimonies regarding Pius’s underground work to help Jews during the time, it has engendered unfavorable responses from the Vatican as well as Catholic and Jewish media platforms alike. Directed by Liana Marabini, Shades of Truth stars Christopher Lambert, Gedeon Burkhard, and Giancarlo Giannini. Here, we revisit Giannini’s explanation of himself and his work in our March 1976 issue.

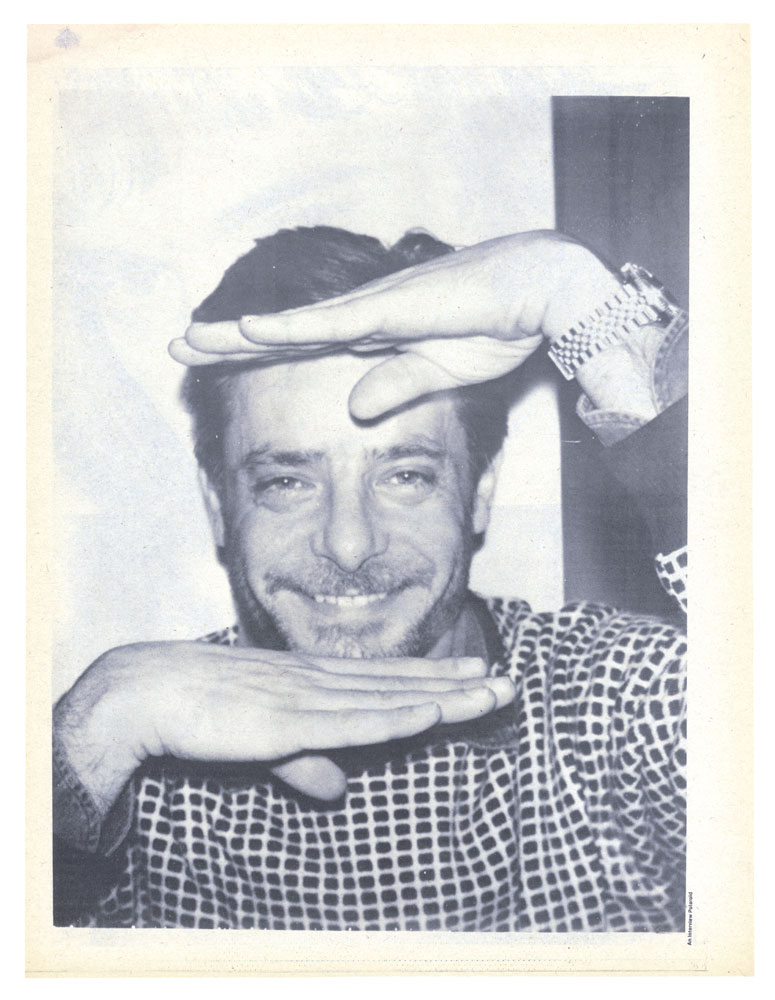

Giancarlo Giannini Explains Himself

Redacted by Chris Hemphill

Giancarlo Giannini is the hot new star out of Italy, the leading man of four films by Lina Wertmuller, the hot new director out of Italy. Giancarlo recently came to New York to promote his latest collaboration with Wertmuller, Seven Beauties, a smash critical and box-office hit. Here he talks about his career and craft:

I finished Visconti’s new film five days ago. It’s a very banal story about the relationship of a man with two women. I tried to make it more interesting since it’s the story of a monster—a man who would be able to kill a child that had just been born and in the end kills himself. But he doesn’t kill himself because he’s sorry for what he did. He kills himself because he decided he doesn’t want to live anymore. It’s the story of Superman. It was taken from a book by D’Annunzio had written at the time the Nietzchean theory was very much in vogue and taken very seriously. I tried, in creating this character, which starts from this way of looking at life, to make it a more modern character, giving him an existential anguish, an incapacity for life. All the actions that he does are therefore very normal.

Luchino’s completely different to work with from Lina. Each director is very different. If they’re not different, I make them different.

Tonio (my character in Love and Anarchy) was a poet, a pure person, an element of nature, a vital force. Tonio’s a tree, a cow, a dog, a cat—he’s very close to the earth. Pasqualino (my character in Seven Beauties) is a monster. It’s natural that the characters that Lina and I do are very Italian. It’s right that they’re so close to us. But even if the character is very close to certain forms of Italian reality it’s always a symbol—a man with arms and legs and a head. They’re always very abstract. In my type of work you work a lot with fiction. When Tonio presents himself to the public you can’t imagine he’s not a fictional character. In fact, I tried to show the make-up on my face. The communication with the public always comes through other lines, other forms that are much more magical. I want to show that everything goes beyond the image and the word. Whether the character’s Neopolitan or Chinese there’s a form of basic communication that must always be abstract. You must see him with an abstract angle and not tied to a form of culture.

Pasqualino was based on a true character. Not even all the things that happened to this man were shown. What we did was a synthesis of the dramatic things that happened to this individual. The ending is our idea. We presented a man who said, “I’m alive,” where in reality he’s dead. It seems to us more proper and more right to show the danger of that kind of life. I think there’s many of these people in the world. In this case the War becomes practically a symbol, a circumference, a circle—the concentration camps presented as a Dantesque circle of hell. But not only the concentration camps can make a man become like this. There are means that are much more subtle to bring a man to this kind of madness. That’s the world we live in today.

I don’t believe much in the strength of words. I believe in the strength of the image. This is not something that I say. Chaplin already did a study on this kind of communication. He said that the image is perceived physically by 82 percent of the spectators, whereas the word, which has to be filtered across the brain, is subjected to a longer process and is perceived by about 8 percent. This is a physical, mathematical fact. This has always surprised me very much, so I’ve always tried very hard to give the most of my energy to the visual image. A Russian theoretician, whose name was Pudovkin as you know surely, once did a very interesting experiment. He took a picture of a person absolutely without expression. He copied it four times and then he did a very strange setting of this picture. He put this picture first next to a woman that was killed, then next to a precipice, then—always this face—next to a pistol, and then, I think, next to a plate of spaghetti. And this face, for the public, acquired four different expressions. And yet it was always the same picture.

These are faces that serve for a kind of expression. When an actor has to portray many types of faces, he needs to practically annul his expressivity for just one thing. He has to have the possibility to do anything. It can be a specific thing that’s very different form what I do in life. If I had to do this part that I’m doing with you in front of a camera, depending in a simple way on the size of the image, I would have to act in a different way. This is my type of technique, which comes in in certain moments. There are moment when this type of expression is given more to instinct.

We haven’t understood yet what an actor is. This is what’s fascinating about the profession. Today for a good actor to do an interpretation is not very difficult. It’s the research of that extra something, that something beyond, that’s difficult. I think each man does this research differently each day until he dies. Often this research can bring on death.

Often little Neopolitan Mafioso types have the habit of giving each other little nicknames. Often you give a contrasting name. When one is ugly you can call him “Sette bellezi” (Seven Beauties). There’s inventions of words of the underworld life. I think this happens all over the world—to name a person who has a poetic fantasy and therefore enjoys himself and also laugh at the name. “Sette Bellezi” in Italy is a title that makes you think of somebody that’s very enjoyable, a very funny character. People were very deluded because when they saw the film they saw that the person was not at all funny, that he was a very tragic person. In Italy, often there’s a refusal to see everything that’s part of human sufferance. It’s for this reason that I often enjoy myself to trick people to make them take roads that perhaps they don’t want to take. This is also part of being an actor. He’s a mystifier.

I like very much to make people laugh. I like to see this form of gratitude on the faces of people when they leave a film. It’s perhaps one of the few things that stays with me. It’s not easy to make people laugh, especially today. I started my acting career by making people cry, which is very easy for me to do.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE MARCH 1976 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.