New Again: Elia Kazan

The name Elia Kazan has popped up a few times over the past few weeks with regards to Interview. In an archive interview reprinted last Wednesday, Tennessee Williams criticized Kazan’s theatrical production of his play, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Then, young actor Ansel Elgort cited Kazan as the director who first sparked his interest in film in our “Young Guns of Hollywood” portfolio.

Born Istanbul in 1909, when Turkey was still part of the Ottoman Empire, Kazan moved to the U.S. as a four-year-old and, as an adult, became instrumental to the gritty realist style of cinema emerging in the 1950s. The writer, director, producer, and editor began his career in theater and co-founded The Actor’s Studio before moving to film fulltime. Between the late ’30s and mid ’70s he directed 21 films, including A Streetcar Named Desire, East of Eden, On the Waterfront, and The Last Tycoon. He also did a few less-great things, like accuse eight people of being communists in an official testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities during J. Edgar Hoover’s “Red Scare.” But so it goes.

Interview interviewed Kazan for our third-ever issue in 1969. He had just finished his 19th film, The Arrangement, based on his novel of the same title.

Kazan on Kazan

By Kent E. Carroll

Two blocks south from where The Arrangement is playing on the west side of Broadway is the Victoria Theatre. The press agent’s directions were descriptive: “The entrance is behind the box office. No, don’t go into the theatre; it’s outside, a small door and at the end of the hall there’s an elevator that’ll take you up to the fourth floor. Kazan’s office is up there. Just look around or ask somebody; his name’s on the door.”

It was. The outer office is small, cramped with two desks and appears very used. Wearing one of those floppy mountaineer hats, off-gray presumably to match the loose sweater, which it doesn’t, the secretary tells you you’re just on time.

Elia Kazan is 60 years old. If one equates outsized talent with physical stature, he is smaller than expected. His office—”I’ve been here forever”—couldn’t contain Ted Ashley’s desk over at Warner Bros. Warner Bros. is releasing the film based on Kazan’s own best-selling novel.

No preliminaries because they don’t seem necessary. Two couches, against a window that opens on the enormous cooling system of the adjacent building, are split by a low table. “I’ll take my favorite side” [says Kazan], so you sit across, bent over to write while he relaxes, one foot on the floor, his graying hair back against two small brown pillows, smoking a cigar that will not be drawn on enough to remain lit.

KENT E. CARROLL: The Arrangement, where does it stand in relation to your other work?

ELIA KAZAN: Actually it is the last part of a trilogy. I’m still working on the middle book, which starts about six years after America, America. It takes me a long time to write though, just the mechanics part. The second draft of The Arrangement dragged out for sixth months.

CARROLL: The Arrangement, how autobiographical is it?

KAZAN: Well, it’s not autobiographical in essence, it’s more general. I didn’t have the problem of finding myself at 45 on the wrong course—I always wanted to be a film director–the details are the same but it’s not my wife or other women I’ve known. Look, does it make any difference? People seem to want it to be my autobiography. Now…Oh, fuck it, people can say what they want.

The second book will be even less so. It’s not like anyone in my family and it gets less and less as it goes along. I find it hard to write in between other things. When cutting on The Arrangement started, I dropped the second book completely—shelved it—but it’s larger and, I think, more ambitious that the other one. In The Arrangement, I said what I wanted to say as plainly as I could. The book is about the tenor of life, about a lifestyle, but the film is better organized, compressed, and compact and, in that sense, superior. [As an afterthought, waiting for the next question] Truth gets buried, that’s why people write autobiographies.

CARROLL: How much control did Warner Bros., particularly Kenny Hyman [ex-production chief] exercise?

KAZAN: Hyman never gave me any suggestions I had to follow; I was entirely independent. The budget went up because of the people we wanted, they’re expensive. I liked Faye [Dunaway] a lot even though Warners suggested her. Kirk [Douglas] had nothing to do with [Marlon] Brando dropping out. Brando wasn’t in any state to do the film. It was painful at the time, but I’ve never had a better working relationship than with Douglas. Brando, of course, is more intuitive, not a verbal man; very, very bright but not analytical. Kirk works with his mind. Marlon works with his instincts—there’s something magical about him. Marlon has done a lot of poor pictures and I wanted to get him at a moment when he wanted to do better work, but it was a mistake. I should have said no immediately.

We had almost a father-son relationship at one time; we understood each other so well. He’s a terrific actor but he was in no condition, he wasn’t capable of working. Kirk is very different, a professional who wants to get better. Kirk’s own father was very much like the father in The Arrangement. He’s had two names; two faces, really, and understands the problems of immigrant families.

There aren’t many male stars —that’s a loose term —like Kirk around. Most of those virile personalities have to keep working, continue the image because they can’t do anything else. They don’t even read. Christ, their real identity is in making those pictures. They have to keep jumping on horses and hitting somebody on the head with a gun.

CARROLL: At what point did writing the book become preparation for a movie?

KAZAN: I never thought it would make a movie. Sure, it occurred to me afterwards, but so much of the writing is internal—it’s a man talking to himself. That’s why I started with the accident and then worked back. I drive into the city on the Long Island Expressway and the police told me that there are accidents, head collisions with abutments of things that have no skid marks. That sense of desperation fit.

CARROLL: The film was cut after a sneak in San Francisco. What and what?

KAZAN: After the San Francisco sneak? Not much. Just some trims. There was a place near the end where the film got off the line. I cut a scene there, but it was really just squeezing, sticking to the subjects. No one had anything to do with the cuts except me. People made suggestions, but, hell [laughs], I don’t actually listen to anybody, I just go my own way. Actually, though, it wasn’t that bad. I’ve only written two screenplays—America, America and this one—although I’ve worked on the screenplays of all my pictures. Next time I’ll do better.

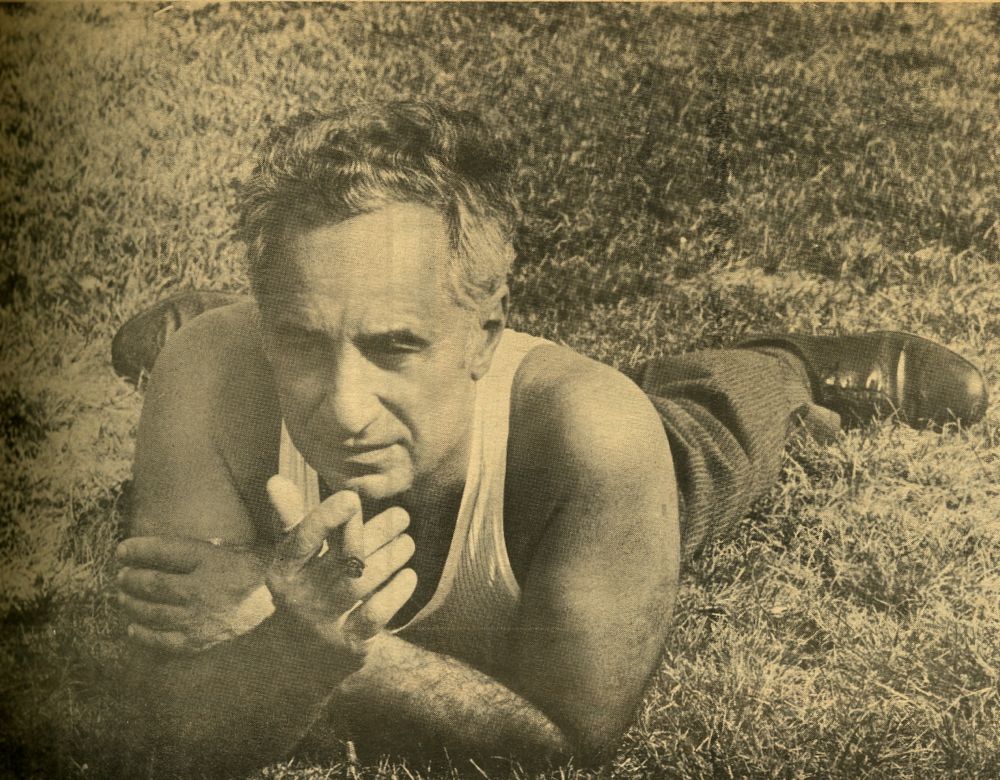

[Kazan, lying with both feet up on the couch, now drawing occasionally on a cigar and sitting up only when relighting becomes necessary, responds easily to questions. No definitions or repetitions required. The answers are more conversation that response. A mind at work while the words flow, but nothing demands hesitation or a measured tone.]

CARROLL: What were the problems of making your own book into a movie and also serving as both screenwriter and producer?

KAZAN: It takes longer to realize that some things may be excessive. But it works well for me because it is more entirely mine. Actually, I had a great time doing it. I’m proud of it and it all came of out me.

CARROLL: Are there any of your films that you’re not proud of or that you didn’t enjoy doing?

KAZAN: No. Well, actually, Sea of Grass. All that process. We were out on the prairie and I didn’t know what the fuck I was doing. [Katharine] Hepburn kept excusing herself to go to the bathroom and every time she came back she had a different dress on. But she is a great actress and if there were any problems they were really mine.

CARROLL: What about future work in the theater?

KAZAN: I won’t go back to the theater. I like some of the things they’re doing but it’s different now, not something I could do. I’ll go on making films the rest of my life. Hell, I’ve got complete freedom. There was absolutely no interference, no pressure on The Arrangement. About 15, 16 years ago, things changed. I produced [Viva] Zapata!, not [Darryl F.] Zanuck, who put his name on it. Selected [East of] Eden and talked Paul Osborn into doing it [writing the screenplay]. Since that time, I’ve made my best films because I’ve had no producer to contend with and that’s because, in essence, whether my name is on the film or not, I produced all my own pictures since then. The only guy who was at all helpful as a producer was Sam Spiegel with On the Waterfront. He’s one of the few who even knows what he’s doing.

I’ve also had a final cut contract since Zapata!. In that respect I’m one of the few. I’m not the highest paid or the most praised, but one of the few in a position of freedom and that’s because I come to them with the property and the people who are going to make the film. It’s my film from the beginning, not theirs.

CARROLL: Were any nude shots cut from The Arrangement? There had been talk that your stars’ genitals were, how shall we say, exposed?

KAZAN: That’s pure bullshit. I even read it in Variety, which surprised me. There was never any pussy or pubic hair or cock. There is nothing dragged in that way, none of the nudity or sex is just put in.

CARROLL: Criticism of your films?

KAZAN: That’s essentially the critics’ problem. I think both the film and the book have great worth and it’s up to the critics to understand. Zapata! and Face the Crowd were both scorned when they came out and so was Splendor in the Grass; now they’re minor classics. I know many of the critics and I don’t think of them as God-like figures. What can they do to hurt me? Sure, I might be slightly embarrassed for a day, but then you just go your own way.

Look [sitting up and playing with a match on the burned-out end of a half-finished cigar], I’ve gotten literally hundreds of letters thanking me. People are moved and isn’t that better than some literary critic on The Times saying I’m not Walter Pater?

The thing with films is that you have to make something that will get people out of their houses, away from the TV set. You must touch people, say something. Otherwise, they’ll stay at home. The NFL is a great show, the most exciting, best-directed thing on television. Sports news is good, too. That’s very, very funny. TV has made us get down to the nub and new films will begin to live up to what the medium can be.

CARROLL: How much did The Arrangement cost?

KAZAN: I never made an expensive picture until this one. The book cost a lot and should have. The thing came in for about six and a half million. But we had to have expensive actors. In the past I found Brando and Dean, put [Andy] Griffith on the screen. With kids you can take a chance but casting a guy at 45 is different. You don’t discover somebody that age. If an actor hasn’t made it by that time he probably has no talent.

CARROLL: How do your films tie together thematically? Do you accept that they are about the perversion of the American dream?

KAZAN: Yes, that’s true for Splendor and The Arrangement. But America, America is a question. It ends with a question: Will America live up to what it means for that character? We have a nervous kind of affluence in this country. All that power and money but what will we do with it? I was born in Turkey in an extremely oppressive climate at the time of pogroms, massacres, really. An immigrant appreciates the freedom more. And to question, to examine, that’s the real patriotic gesture. I’m very pro-America, but I feel it necessary to keep in touch with Europe to maintain a perspective.

CARROLL: Can we go back to how much of your life, not actual experiences, not the specifics, but attitudes and values are reflected in the thematic content of the films, in America and The Arrangement?

KAZAN: Sure? Look, a lot of men die by 35 just haven’t announced it yet. Some men at 45, they don’t have any sex left. What I did since I left Lincoln Center was to begin a new life. My wife died, I took a trip around the world, I remarried [actress Barbara Loden whom Kazan directed in Arthur Miller’s After the Fall at Lincoln Center]. I lived one whole life, 32 years acting and directing in the theater. I left the theater; I literally left to begin a new life. That’s one of the reasons Kirk worked out so well. He’s still coming on.

CARROLL: Who else did you consider for the leads in The Arrangement?

KAZAN: Well, I found Faye up in Boston and brought her to Lincoln Center although, as I said, Warner Bros. did suggest her. Actually, at one time I thought of [my wife] Barbara playing Faye’s part. She might have been great.

CARROLL: What do you see as the essential function of the director? For example, Hitchcock says he cuts in the camera. Did your technique vary with a film for which you also wrote the screenplays?

KAZAN: Not, not really. Cutting is very important. Shit, nothing would be worth making a film if you couldn’t cut it yourself. George Stevens said it and I agree; cutting is a third of directing, it’s as important as the actual shooting, which is the other third. The casting and preparation work is also worth a third. Hitchcock cuts the camera and he’s a master. The way he sets up shots and puts them together. But I can’t do that. I play for all the possibilities. I give myself as much range, as much opportunity in the cutting room as possible. Some directors, like Stevens, shoot full circle, 360 degrees, and that’s what’s right for them. I generally shoot at about a seven to one ratio. But part of that is because I’ve worked on every screenplay, so I’m further along in the visual concept.

CARROLL: If you hadn’t directed The Arrangement, who would you have liked to see do it?

KAZAN: Never occurred to me. It just worked out. The book, it sold an enormous amount of copies and then the sale for the film. This was a chance to subsidize myself and my family for a number of years. I’ll never write another book that’ll sell like that. But this was important. I got a good piece for the family, even if the critics don’t like it. They were patronizing to Face in the Crowd and Zapata! and Baby Doll. Baby Doll was written by the best poetic playwright in this country. The Times went out of their way to rap The Arrangement twice, and then they had to publish those best seller lists with the book right on top for almost a year. I’ll just do what’s mine my own way, the best I can. For the rest of it, I say fuck ’em.

THIS ARTICLE INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE THIRD ISSUE OF INTERVIEW PUBLISHED IN 1969.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.