New Again: Daniel Day-Lewis

On Tuesday Daniel Day-Lewis announced that he will retire from acting after the completion and release of Phantom Thread, a drama directed by Paul Thomas Anderson about the 1950s London fashion scene. For many, this is somber news, as the celebrated British actor has delivered one hypnotic performance after another, both in film and theater, for over three decades. Making Phantom his last film marks a full circle from one of Day-Lewis’s biggest achievements: winning the 2007 Academy Award for Best Leading Actor in another one of Anderson’s films, There Will Be Blood. Day-Lewis has received praise and awards for numerous roles, in TV dramas and large-production historical epics alike (he has two additional Best Actor Oscars for My Left Foot and Lincoln, and has been nominated five times in total). He has morphed seamlessly into diverse personalities, from a gay, working-class youth with a skinhead past (My Beautiful Laundrette, 1985) and a lonesome warrior of a Native-American tribe (The Last of the Mohicans, 1992) to a former President. He has undeniably claimed a permanent spot in cinema’s history.

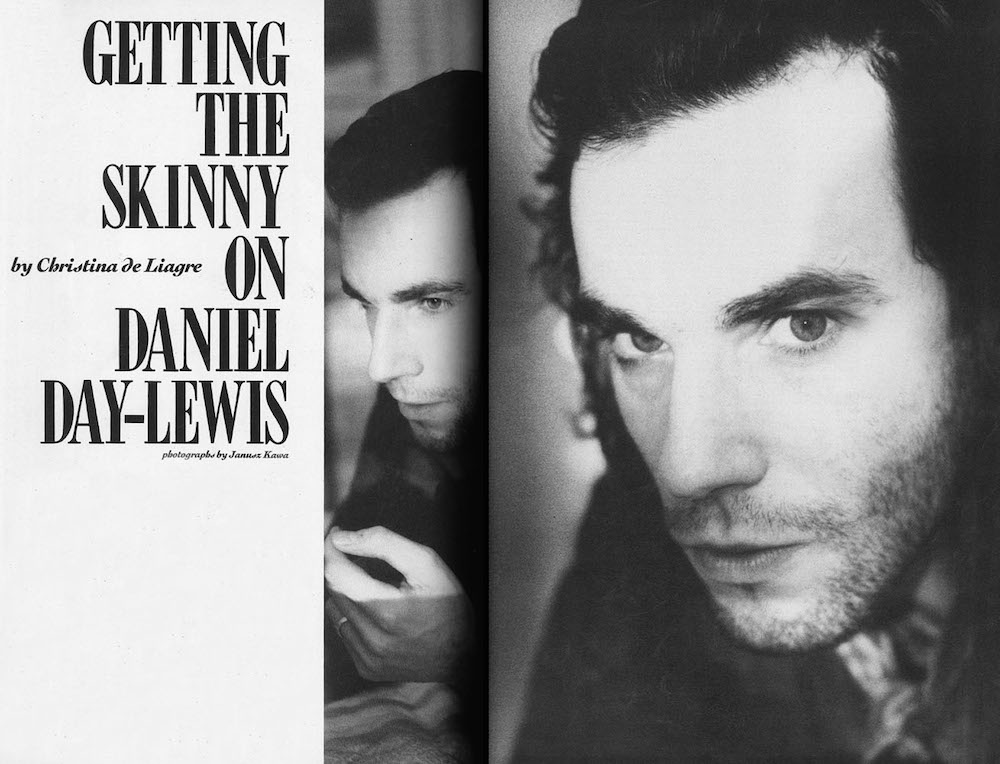

Before we bid farewell to Day-Lewis, we look back at an interview with the now 60-year-old actor in our April 1988 issue, in which he discusses exorcising past roles and his commitment to the theater. —Zuzanna Czemier

Getting The Skinny on Daniel Day-Lewis

By Christina de Liagre

As his father, the poet Cecil Day-Lewis, put it, “The Newborn” Daniel “broke prison and stepped free into his own identity” on April 29, 1957. Years later he broke away again, this time from the confines of English public school into the freedom of the multiple identities of acting—first at the Bedales Progressive School, then on to the Bristol Old Vic, before emerging in London’s West End as Rupert Everett’s replacement in Another Country. “There are lots of reasons why people become actors,” Ralph Richardson once said. “Some to hide themselves, and some to show themselves.”

The true identity of Daniel Day-Lewis is a subject of speculation on both sides of the Atlantic after his virtuoso screen performances in Stephen Frears’ My Beautiful Laundrette, Merchant/Ivory‘s A Room With a View, and Philip Kaufman’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Take one: Johnny, the gay, tough street punk. Take two: the priggish suitor Cecil. Take three: the inveterate womanizer Tomas, a Czechoslovak brain surgeon at the time of the 1968 Russian invasion of Prague. Take four: Henderson Dores (in the still unreleased Stars and Bars), a comically uptight British art dealer who comes to America.

Like Robert De Niro, the original “goddamn chameleon,” Daniel Day-Lewis has the uncanny ability to transform himself beyond recognition—perhaps an inherited trait. After all, his father nurtured a double identity: he was England’s poet laureate (though proud of his Irish roots) and at the same time wrote detective stories under the pseudonym Nicholas Blake. He and Jill Balcon, his stage-actress wife (of Eastern European Jewish stock), named their last-born Daniel because “it mixed Jewish Old Testament associations with those of Daniel O’Connell, the barrister who fought for Catholic emancipation in Ireland during the 19th century.” Daniel Day-Lewis embodies the interplay of these disparate legacies. The first to blaze the trail into show business was his knighted grandfather, Sir Michael Balcon, whose family were refugees from Riga. As the head of Ealing Studios he produced Passport to Pimlico, Whisky Galore, Kind Hearts and Coronets, and The Lavender Hill Mob.

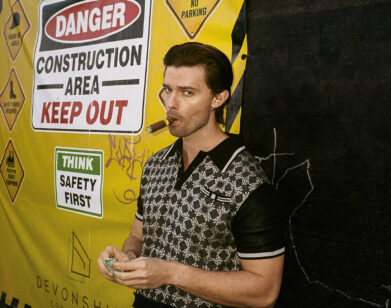

Day-Lewis has been compared to Laurence Olivier, Montgomery Clift, and Cary Grant. Others have pegged him as “someone who lives out of a paper bag.” The real Daniel Day-Lewis steps forward for this interview with shoulder-length hair and a three-day stubble in the lobby of the Hotel Lancaster on rue de Berri, off the Champs-Elysees. He still can’t get over the French routine: “You convene at 10:30 in the morning, kiss each other a lot, and then sit down to a three- or four-course lunch with wine. I used to be up at 5 in the morning waiting to work!”

Gaping holes in the knees of his jeans reveal black leggings underneath. There are many layers to the onion. Questions about his private life are answered with a broad smile: lips never parting, the delicate skin around his mouth rippling outward as though you’d thrown a stone into unfathomably deep water. He punctuates his thoughts with ready laughter and can be charmingly self-deprecating: “My nose was the same when I was a kid in Sunday, Bloody Sunday. I just grew around it.” As I prepare to leave with the tape of our hour-long conversation, Day-Lewis gives me a single word of advice: “Eliminate.”

CHRISTINA DE LIAGRE: Do you know Paris well?

DANIEL DAY-LEWIS: Paris always remains a mystery. I didn’t really get to know it even when we were filming The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Of course, I spent a great deal of the time resisting it, since it was important to believe we were in Prague. In all, we spent six months shooting in France. I came back to Paris last summer because I wanted to look around, look up for a change instead of looking at my feet. And I did love it. But Paris infuriates me as well.

DE LIAGRE: Why?

DAY-LEWIS: Because there’s something provocative and tantalizing about it. It makes me quietly dissatisfied with living in London.

DE LIAGRE: You’ve just bought a house in London?

DAY-LEWIS: Quite recently. But I feel like a guest in it.

DE LIAGRE: Because there’s nothing there?

DAY-LEWIS: Partly. But partly just because I choose to feel like a guest in the house.

DE LIAGRE: Have you been taking time off recently?

DAY-LEWIS: Ever since Stars and Bars.

DE LIAGRE: What’s the situation with that film now?

DAY-LEWIS: Pat [O’Connor, the director] and I, who don’t go down without a fight, have been using every possible opportunity to vent our spleen against the system, which is prepared to sweep some years of work under the carpet because of their own prejudice and for their own convenience.

DE LIAGRE: Columbia has got it tied up, is that it?

DAY-LEWIS: Well, I understand things are loosening up a bit now. I wouldn’t be so arrogant as to presume that we’ve had any part in that. But anyway it seems that the film might, if we’re very lucky, be shown in one cinema in New York, so people will be allowed to judge for themselves, which is all you can ask for. We’re not going around saying this is a wonderful film which should be seen, because we’re not in a position to judge it in that way. But we devoted a great deal of our time to it. Pat was on it for three years. I kept faith with it for two years before we were finally allowed to make it, but it appears that through the obscene prejudices of a few people such things can be swept under the carpet. I find that really despicable.

DE LIAGRE: Do they question the film’s commercial potential?

DAY-LEWIS: I can’t say what the trouble is. I suspect I know why they’re sitting on it, and it’s got nothing to do with the film.

DE LIAGRE: Are you happy with your work in it?

DAY-LEWIS: When I was doing it, I was. Now it doesn’t belong to me anymore. At the time it was something I wanted to do. It was something I was prepared to wait to do. And I did it at a time that was grossly inconvenient. I had just finished six months on The Unbearable Lightness of Being and I was ready for a rehabilitation center. I wasn’t race-tuned. I was clapped out. Had it not been for my desire to work with Pat on this project, I’d have even broken contract.

DE LIAGRE: So you have no particular project in line right now?

DAY-LEWIS: I did up until a couple of weeks ago. I was going to work in Patagonia with a wonderful Argentinian director, Carlos Sorin. We were going to do a film called Ever Smile, New Jersey. I had been preparing for it for two or three months. But we placed ourselves in the wrong hands, and the money was not forthcoming.

DE LIAGRE: Do you think that you’re in danger of being overexposed at the moment?

DAY-LEWIS: I don’t think there’s any danger of that, no. [laughs]

DE LIAGRE: Have you exorcised the role of Tomas in The Unbearable Lightness of Being yet?

DAY-LEWIS: I’ve said “yes” a number of times over the last few months, but I think “no” is probably a more truthful answer. [laughs] The truth changes from day to day, but I think on balance “no” is closer to the truth because I’m still haunted.

DE LIAGRE: Specifically by that part, or would that apply to Henderson in Stars and Bars as well?

DAY-LEWIS: Well, Henderson had a strange life; he had a very vivid, complete life while was working on that film. But there was an extent to which Tomas was locked in the cupboard during the day. I do have, I think, quite substantial powers of concentration, so the character didn’t bug me during the day. But Tomas was waiting to be confronted because I hadn’t gone through the period of interment with him. I hadn’t been able to scatter the earth over Tomas. As a result, he is a kind of lost soul and he appears from time to time. Especially when I’m in this fucking city. It’s not easy being here. I don’t find myself generally in a kind of carnivorous pursuit, but he is still around. When you finish making a film, someone tells you that it’s over; but, you know, what does that mean? It never is.

DE LIAGRE: One of the questions from the press that you avoid is anything concerning your private life, specifically the alleged relationship with your costar in Being, Juliette Binoche. Does that make the whole experience of the movie even more emotionally charged?

DAY-LEWIS: Does what make it even more emotionally charged? The “alleged” relationship? [laughs] Well, why would something that’s allegedly true make it more difficult? What are you trying to say? If I have avoided the question up till now, is it likely that I’ll start speaking about it at this moment?

DE LIAGRE: I’m not asking you to speak about it, but it would seem that it was a highly charged production from many points of view.

DAY-LEWIS: I can’t account for what people say. They allege what they want to allege. I haven’t contributed to that and I don’t intend to. They’ll just have to draw their own conclusions…

DE LIAGRE: Have you kept up with friends from school? In your letter to director Stephen Frears approaching him to get the part of Johnny [in My Beautiful Laundrette] you wrote, “I know you think I come from a public-school background, but I’ve got very nasty friends.” Who are they?

DAY-LEWIS: Well, if ever you’re in London I’ll take you to a football match in Newcross; you can watch Millwall playing, and then you’ll find out. They’re actually doing rather well as footballers now, but in the past they had a reputation as the most badly behaved supporters in the country, probably in the world. They’re very naughty boys.

DE LIAGRE: And are they still part of your entourage?

DAY-LEWIS: [laughs] Well, I was part of their entourage. I was just sort of tagging along! I was a shrimp.

DE LIAGRE: How do you feel about Stephen Frears describing your letter as “vile and disgusting”? Was it?

DAY-LEWIS: He’s embellished on this story. When he was first trying to do Prick Up Your Ears years ago, I went to meet him and I suppose I was fairly bizarrely dressed. But according to him now, I went into the room and he said, “Why are you talking in a working-class accent? You’re the poet laureate’s son.” He never said that to me; he had no reason to. I wasn’t talking in a working-class accent. He just exaggerates. The letter was fairly vile, but I only wrote it to him because I knew he would understand it. He’s not easily intimidated and it wasn’t intended to intimidate him; it was just making a point and he took the point—he gave me the job! He didn’t give it to me because I threatened—

DE LIAGRE: –to break his leg, was that it?

DAY-LEWIS: Uh, both of them. He gave me the job because he understood my enthusiasm.

DE LIAGRE: You have said that one of the burdens you carry is the fear that people are going to find you out one day: “The thing about acting is that you always believe you’re a fraud.”

DAY-LEWIS: The truth is that the work you do is, at best, a rather wonderful, intricate fabrication of an untruth. The greater your powers of self-delusion, the greater will be the apparent efficacy of this untruth. My life is devoted to self-delusion—and I have a great capacity for that—but it’s the thing that gives me the most pleasure, so I can’t complain about it.

DE LIAGRE: Your first film was Sunday, Bloody Sunday [1971], when you were 12 years old. Is that correct?

DAY-LEWIS: Well, not entirely. I was hired as a professional footballer at that time. I was paid two pounds a day to play football in the background in Greenwich Park. Now there happened to be a camera at some distance from us, and John Schlesinger happened to be behind that camera, but as far as I was concerned I was making my debut as a professional footballer. That’s what I was hired for. Then he asked to see a few local boys and chose three particularly unpleasant-looking ones. I was one of these. We were equipped with broken milk bottles and told to wreck a row of rather smart parked cars. It doesn’t sound like film work to me. That sounds like money for old rope. [laughs]

DE LIAGRE: I heard something about how you once wanted to be a carpenter.

DAY-LEWIS: A cabinetmaker. It’s true. I made furniture when I was at a school which had facilities for that. It gradually became more and more important to me until I reached a point where it threatened my perception of the theater, a perception which had been unshakable from the age of 12 onwards. Suddenly, weighing the two things, the theater seemed to be an occupation to be deeply mistrusted, as opposed to the honest, tranquil world of craftsmanship. It has to do with the fact that I met a number of master craftsmen during that time and without exception they seemed to have found the secret as far as I was concerned. They were peaceful, beautiful men and I suspected that as long as I worked in the theater I would never find the secret.

DE LIAGRE: And you haven’t?

DAY-LEWIS: No, of course not; that’s why I still doing it.

DE LIAGRE: Your mother was an actress.

DAY-LEWIS: She is an actress. It was harder for her when we were growing up and she did less work.

DE LIAGRE: You have an older sister, Tamasin—

DAY-LEWIS: –and two half brothers, Sean and Nicholas.

DE LIAGRE: What was it like being the son of poet laureate?

DAY-LEWIS: We were tremendously proud of work that he did. He died in 1972, when I was 15—before I’d had a chance discuss anything that was important to him—that’s something to be regretted. He my father. There’s nothing else to say.

DE LIAGRE: Do you have a favorite line or favorite poem of his?

DAY-LEWIS: There are a number of his which I particularly like. I like the the poem he wrote for me—for obvious reasons called “The Newborn.” He also wrote a poem for my brother Sean, called “Walking Away,” which I think is beautiful. There is a bit at the end which I think is particularly good: “I’ve had worse partings, but none so / Gnaws at my mind still. Perhaps it is roughly / Saying what God alone could perfectly show— / How selfhood begins with a walking away, / And love is proved in the letting go. [Both poems are in The Gate, Jonathan Cape, 1962—ed.] I think that’s wonderful. He wrote it for my brother, his eldest son, when he took to school for the first time.

DE LIAGRE: Your father was quite old when you were born.

DAY-LEWIS: Yes, he was 53.

DE LIAGRE: You said recently that you weren’t ready to get married.

DAY-LEWIS: No, I’m not ready… No.

DE LIAGRE: I only brought that up in terms of your father having been 53 when you were born.

DAY-LEWIS: Oh, you think I’m heading dangerously towards the time when I’ll be… [laughs] I wouldn’t like to be that old when I have children. While he was a very affectionate father—he was—it was difficult. His age certainly created a distance which I wouldn’t choose for my own children. But then his work created a distance as well. He was a man who needed a great deal of solitude and privacy for his work, something that we respected, but one can say that that was as much a reason as his age for that distance. One can’t dissociate the two things. I would like to have children while I’ve still got the energy. But then I have the feeling that when I have children I’ll stop performing in the same way, because you don’t really need to perform if you have children.

DE LIAGRE: Why is that?

DAY-LEWIS: Well, they’re naturals; they’re the best performers. I’ll become a director when I’ve got children and just sit and watch. [laughs]

DE LIAGRE: After having done these films is it important to you to get back to the stage?

DAY-LEWIS: The theater is a need for me. It’s a terrible attraction, something I’m compelled to do. And one derives a form of nourishment from the theater which you can never get from films. Making films weakens you in some way. With the theater, the work itself is a regenerative process. Now, when you make a film that costs $15 million, there’s a part of you which can’t help thinking, “Well, couldn’t this money be better spent?” I continue to make films because it still has a fascination for me, but it’s not easy to justify…

DE LIAGRE: Do you have certain heroes or role models?

DAY-LEWIS: No role models. Many heroes. I have an enormous capacity for hero worship. Right down to the Millwall terraces. Spencer Tracy. Montgomery Clift. Brando—how can you not worship Brando? Guinness. Richardson. Paul Scofield—

DE LIAGRE: The heroes are all men!

DAY-LEWIS: You didn’t ask me about heroines, you asked me about heroes. [laughs] I’ve got many heroines, too. Katharine Hepburn—she’s my ideal woman. Sissy Spacek. Meryl Streep. Audrey Hepburn. In my own country, Peggy Ashcroft is a most divine woman.

DE LIAGRE: Are you very solitary? Didn’t I read that when you were doing Stars and Bars you took a cabin up in the hills by yourself?

DAY-LEWIS: Yes, I did. I don’t like to dissociate myself from the people I’m working with, but that was a very particular time. I needed to restore myself, and silence for me is one of the greatest restoratives. And the Blue Ridge Mountains are the most silent place on God’s earth.

DE LIAGRE: It’s always difficult to ask if there is any particular director whom you really would like to work with. I know other actors say it sounds as if you’re asking for work.

DAY-LEWIS: I admire Scorsese very much—why pretend otherwise? Of course I’d like to work with him. In this country I’m a great admirer of Alain Cavalier’s work.

DE LIAGRE: Do you feel a lightness of being?

DAY-LEWIS: Occasionally. One is allowed flashes of naïveté from time to time, flashes of a remembrance of some innocence. But I’d be deeply mistrustful of anyone who remained in that state for very long. [laughs]

DE LIAGRE: After Bristol College and before things really got rolling, were there very bad moments? Did you have a particularly difficult time?

DAY-LEWIS: No. I had far too easy a time of it my first year, which made things terribly difficult when I arrived in London, thinking it was all going to be like that. I’d done very well in Bristol—I’d joined the repertory company of the Bristol Old Vic, which I’d aspired to from the time I first went to the theater school. I spent a year in a repertory company playing very interesting parts in good plays. [laughs] That’s when the power decided that it was time I was brought to heel. Even now a lot of my mates have been out of work for a year. Imagine what it’s like after three years of training. You have such an intense desire to inflict yourself upon a paying audience.

DE LIAGRE: Where are you going from here?

DAY-LEWIS: To Rome to promote the film.

DE LIAGRE: What kinds of things, without being indiscreet, do you do at night?

DAY-LEWIS: I have a troubled sleep fraught with bad dreams on the whole—dreams of indiscretion.

DE LIAGRE: I was wondering whether you’d ever heard of the “questionnaire de Proust,” which is a series of questions devised by Proust—

DAY-LEWIS: –from which you can divine everything about a human being? No, I haven’t ever heard of it.

DE LIAGRE: What about the question, “What quality do you like best in a man?”

DAY-LEWIS: In a man? [long pause] Femininity.

DE LIAGRE: And “what quality do you like most in a woman?”

DAY-LEWIS: [laughs] I don’t need to answer that, do I?!

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE APRIL 1988 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.