New Again: Clint Eastwood

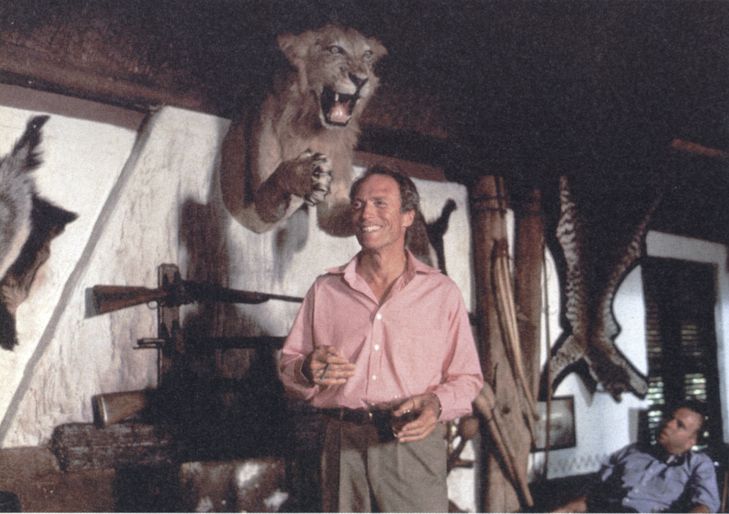

MAKE MY PREY: CLINT EASTWOOD WITH TIMOTHY SPALL IN WHITE HUNTER, BLACK HEART (1990).

Clint Eastwood’s political leanings are no secret. The actor, director, scowling icon, and soon-to-be reality star has publicly supported the presidential campaigns of Republican Richard Nixon (although post-Watergate, Eastwood did criticize Nixon’s morals during an interview with Playboy), and was once mayor of Carmel in California (apparently his platform concerned the removal of a ban involving ice cream). Most recently, Eastwood gave a colorful speech endorsing Mitt Romney at the Republican National Convention. Eastwood is a rare Republican spokesperson in Hollywood—a town that, according to Eastwood’s speech, is perceived as “left of Lenin.”

When Graham Fuller spoke with Eastwood for Interview in October of 1990 (reprinted below), the conversation naturally wandered to the subject of politics. Eastwood proclaimed himself a “liberal libertarian,” with no plans to run for President and also addressed the conservatism ascribed to one of his most popular films, Dirty Harry (1971). —Emma Brown

Clint Eastwood: The Man Who Would be Huston

By Graham Fuller

Clint Eastwood turned 60 in May, but there was no conceit in his decision a year before to cast himself as John Wilson —a pseudonym for John Huston—in White Hunter, Black Heart. Although Huston was a youthful 44 when, in 1951, he took Bogart and Hepburn to the Congo to shoot The African Queen, and made them sit in the heat while he tried to bag himself an elephant. It was a fixation, Eastwood’s film suggests, that brought him to a reckoning with his neurotic Hemingwayesque posturing. Eastwood’s nuanced portrayal of a vain, fond, mercurial intellectual with brutal impulses makes perfect sense. In the era of Total Recall and the Die Hard movies, Eastwood’s oeuvre looks increasingly askance at the burden of male prowess.

White Hunter was Eastwood’s 14th film as a director, and he has gone on to make the cop drama Rookie. I met him at the Westwood Marquis, where he arrived from a skiing trip, suntanned, graceful, quietly spoken, but scarcely laconic, the possessor of a rueful smile who isn’t about to take any of this “icon” stuff too seriously. Unsolicited, the restaurant pianist played “Misty” for him and Van Johnson came over to pump the former mayor of Carmel’s hand. We talked about Einstein, Rawhide, the Korean War, and gun control, but mostly about John Huston.

CLINT EASTWOOD: Yeah, it’s pretty well based upon the pre-production of The African Queen. There was a lot of tension over Huston’s obsession with elephant hunting, and even in his book he talks about going off on a three-week safari, leaving the crew just sitting around. He admits to being possessed, though he claims he never shot an elephant, and Peter Viertel backs that up. Of course, I am sort of anti-hunting. I don’t put down what anyone wants to do, but it seems to me that… er… killing a creature for fun is not a [pause] progressive idea. [laughs]

GRAHAM FULLER: Have you ever had the urge to hunt?

EASTWOOD: Oh, I did as a kid and everything. It’s probably one of the oldest things that mankind’s done, but by the same token there’s a certain kind of obsolescence about it. And I guess I just like animals a lot. But I was kind of interested in Huston’s obsessions because he always seemed to have one, but more so on this film. Though he managed to make really fine films, there was seemingly some distraction on all of them, whether it was racehorses on one or a woman on another. Most people envision a fine filmmaker as someone who puts everything in the world into his picture, but in his case that didn’t seem necessary.

There was an incident that was supposed to have happened during The African Queen, which Katherine Hepburn talks about. She was doing this scene with Bogart in the back of the boat and Huston was up at the bow, fishing. And she said, “John, you’re not watching me.” And he replied [in theatrical upper-class English accent], “I can hear you, darling, I can hear you.” Maybe he’d seen the rehearsal and kind of knew what was going on; maybe just keeping that partial attention was what his great talent was—to never get too wrapped up, to know when something was right.

FULLER: Did you know Huston at all?

EASTWOOD: I never knew him, no. Before going to Africa, I looked at most of the documentaries on him and listened to talks he’d made, public-service announcements, and American Sportsman shows. I sat next to Anjelica at a party and talked to her. She wasn’t that familiar with that era in his life, but she did say that Peter Viertel’s book probably had a little more truth than poetry in it. [laughs]

FULLER: Huston’s mannerisms, his voice, the walk, even his gauntness were very recognizable in your performance. Was there a point at which you thought, Am I going to play it a bit like Huston, or a lot like Huston, or am I going to play it my own way?

EASTWOOD: No, I just looked at a lot of Huston’s delivery and though in terms like that. He had a certain patronizing quality and a certain paternal quality, and I just though about that and let it happen. His enunciation was a little bit [Huston accent again] conscious of the way he… You know, when he’s talking to you, he’s commanding everyone to listen. It’s very difficult with that particular kind of character not to want to… I mean, I used to do an imitation of him, but I didn’t want to do a Rich Little number. Huston himself, though, would have probably been much more exacting. He would have highlighted the characteristics—I just sort of took on the feeling.

I guess I could have played it completely differently, but I kinda liked the Huston character. Some of the philosophies he expounded… Huston could be an extremely personable person, but at the same time he could be very cruel to his friends and neighbors, depending on the mood he was in.

FULLER: Did you understand the contradictions in a man who could be very humanitarian? I’m thinking of the scene when he attacks that colonial woman’s anti-Semitism and the goes out and commits what he himself describes as a sin by trying to slaughter an elephant.

EASTWOOD: Yeah, I could understand it. I think everybody has something that they’ve been obsessed about in their lifetime. Maybe it’s large, maybe it’s small; in Huston’s case it was large—everything he did in life was large. He was sort of a bigger-than-life character.

FULLER: Was it interesting to direct yourself as someone perhaps more intellectual, more lettered, than most of the characters you’ve played?

EASTWOOD: Yeah, it was fun. I don’t know if I can give any anecdote that relates to that. It was interesting because the character was such a dichotomy. On the one hand, he tried a rough-house, and on the other hand, he was a self-educated man, an incessant reader. When he was a kid he was misdiagnosed with a heart problem by his doctors, and it was thought he was going to die at 25.

FULLER: Maybe that’s what made him live on the edge to some extent.

EASTWOOD: Yeah, maybe he thought, what the hell? I’m going to live beyond my expectations.

FULLER: When I watched Bird, I felt very strongly that the rhythms of the film took their cue from bebop itself.

EASTWOOD: Mmm hmm.

FULLER: So how did you find a style for this film?

EASTWOOD: Being raised in the bebop era and still enjoying music, I didn’t have think too much about that. Bird just took on a life of its own, and so did this film. I knew that is was a long shot: it’s not in any genre particularly, it’s not a film where I’m charging through walls. It’s a film that’s got a certain thoughtfulness about inner conflicts. I didn’t recall at the time duplicating any shots that I’d made before, and I hope I’ll stay that way.

FULLER: Do you think White Hunter could be a problem picture for Dirty Harry fans?

EASTWOOD: It could be, but I’ve made problem pictures before and sometimes people tell you they’re a problem and other times they don’t. I have to assume that some Dirty Harry fans like different types of movies. Honkytonk Man was definitely a problem picture, and even with The Gauntlet, people didn’t necessarily want me to play a dumb detective. The woman in that film was much smarter than he was, so that became a problem. You have to lead the audience in different directions, otherwise they might dump you eventually. Everybody—my agent, my lawyers—they said don’t do Every Which Way But Loose, and even one they saw it, one of the studio execs thought it was going to be a flop. I always thought it was kind of a hip script with the orangutan and stuff. Some people got it and some people didn’t, but the public seemed to enjoy it.

FULLER: Do you feel sometimes that your films and the way people perceive you have been basically misinterpreted—I mean politically?

EASTWOOD: Probably, yeah. Because I grew up with a kind of live-and-let-live attitude. I guess—

VAN JOHNSON: [approaching raucously with two friends] Mr. Mayor, I hate to interrupt but I’m your biggest fan.

EASTWOOD: And I’m a fan of Van Johnson. How are you?

JOHNSON: Are you still the mayor?

EASTWOOD: No, it was only a two-year term. I’ve been out of there almost three years now.

JOHNSON: You look like Shirley Temple. What’s your secret?

EASTWOOD: Well, I’ve got to curl my hair a little bit. [general laughter]

JOHNSON: White House, next stop.

EASTWOOD: No chance. See you later.

JOHNSON: See you later. Smile, smile.

EASTWOOD: I will. [Van Johnson and friends leave.] Those guys look like they’re out to get into trouble, don’t they? I remember him from the bobby-soxers era. What were we talking about?

FULLER: They way your films have been interpreted politically. I always thought they were a bit more liberal than people gave them credit for.

EASTWOOD: People jump to conclusions. I think it dates back to right-wing connotations being put on Dirty Harry, which were never intended anyway, certainly not by the director. I guess I would like to be interpreted as a liberal libertarian, like leave everybody alone and let them do their own thing. But as an actor you play a lot of things that you don’t agree with. It’s the same as playing a character like Huston, who could be so oppressive and selfish, yet very generous and supportive of the underdog. I don’t know whether that was a conscious thing—I imagine he must have felt that way in his soul.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE OCTOBER 1990 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again, click here.