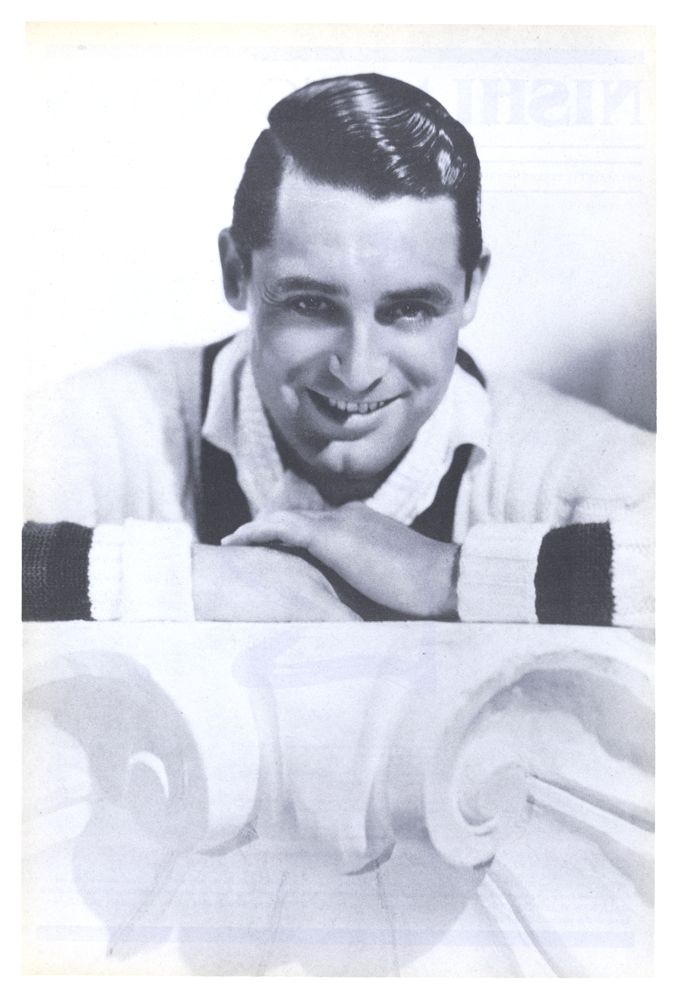

New Again: Cary Grant

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

If we need a reason to celebrate Cary Grant, it is that Charade, one his last films and his only film with Audrey Hepburn, turns 50 this year. Grant was hesitant in accepting the role—he was 59 at the time and Hepburn, who played his love interest, was 25-years his junior. Three years later, Grant would retire from film for good.

Interview spoke with the iconic actor shortly before his death at the end of 1986. Topics of discussion ranged from Grant’s earliest ambition to the youth of the 1980s, rock music, how he’d like to be remembered, working with Hitchcock, and his favorite female co-star.

Postscript: Hollywood’s Leading Man

By Kent Schuelke

Cary Grant left the world in the same fashion as he lived—quietly. Within 48 hours of the 82-year-old actor’s death on November 29th from a massive stroke in Davenport, Iowa, his remains had been flown to California and cremated. No funeral, no memorial service. That’s how Grant wanted it. Outside of his illustrious movie career, spanning 72 films, Grant shunned the spotlight, seldom giving interviews.

Born Archibald Leach in Bristol, England in 1904, Grant came to the United States in his early teens as a performer in a traveling acrobatic troupe. His talents led him to the Broadway stage, where he performed in musicals. A movie contract with MGM soon followed. To many critics, the debonair Grant was the greatest comedian in the history of cinema. Along with Howard Hawks, George Cukor, and Frank Capra, he helped invent the “screwball comedy.” With his sweeping charm, clipped accent and impeccable timing, he lit up some of Hollywood’s greatest comedies, including Bringing Up Baby, Topper, The Awful Truth, and The Philadelphia Story. In those films, he costarred with many of Hollywood’s leading ladies: Katharine Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe, Mae West, Ingrid Bergman, and Grace Kelly. But probably Grant’s most important collaborator was Alfred Hitchcock, with whom he made North by Northwest, Notorious, and To Catch a Thief.

Retiring from cinema in 1966, Grant spent the rest of his days in business, on the board of directors in at MGM and Faberge Cosmetics. He enjoyed his privacy, but his marriages—to Virginia Cherrill, Barbara Hutton, Betsy Drake, Dyan Cannon, and Barbara Harris—and his four divorces, brought him unwanted and unflattering publicity. In spite of such controversies, the public always loved Cary Grant.

This interview with Mr. Grant was done four months before his death. He did the interview in connection with a film tribute in his honor at the University of Iowa in Iowa City. This is one of the last public conversations with a legend.

KENT SCHUELKE: What was your earliest ambition?

CARY GRANT: My earliest? I don’t know, just to keep breathing in and out, I guess. I had no definite ambition. One has to go through one’s education before forming thoughts about what one wants to do. Unless you’ve got some mad ideas about being a fireman or a great boxer or a football player. But I had none of those.

SCHUELKE: What about acting?

GRANT: I had no ambition toward acting.

SCHUELKE: I understand that as a boy you dreamed of traveling the high seas. Did you want to be a sailor?

GRANT: Yes. I had ambition to travel. I was born in a city—Bristol—from which there was a great deal of travel. It was a very old city, and in those days the ships came and left all the time from the port. I was constantly interested in what was going on down there and in those ships that took people all over the world.

SCHUELKE: How did you get started in acting?

GRANT: Because of my wish to travel, I joined a small troupe of ground acrobats. I first came to New York with the troupe. When the troupe went back to England, I remained here. I liked this country very much, and gradually I got into musicals. In those days, a musical generally only lasted a year, so there weren’t very many. But I was in musicals before I came to film.

SCHUELKE: Young people who weren’t even born when you made your last film are now discovering you in your classics. What do you think about that?

GRANT: I think they have a long life ahead of them. They will make their own choices. I hope for the very best for the coming generation, but it doesn’t seem to promise too much. But in every century people complain about how the world is going. I don’t know what the young people think or do; I only hear the emanation of their thoughts—rock groups and similar noises. But if that’s what makes them happy, fine—as long as they don’t do it next to me.

SCHUELKE: How do you see yourself?

GRANT: How can I see myself? We are what we are in the opinion of others. It’s up to them to make up their minds as to what we are. I can only see myself as a man of 82 who keeps on functioning. I do the best I can under the circumstances in which I’ve placed myself.

SCHUELKE: How would you like history to remember you?

GRANT: As… “a congenial fellow who didn’t rock the boat,” I suppose.

SCHUELKE: Is your life relatively quiet these days?

GRANT: I live pretty quietly—but what else does one expect a man my age to do?

SCHUELKE: Is that how you want to live out the rest of your life, quietly in Beverly Hills?

GRANT: I don’t know how long that’s going to be—”the rest of my life”—but I enjoy what I am doing and, of course, I shall live out my life here unless some extraordinary change suddenly occurs. If I didn’t enjoy living in Beverly Hills, then I would move—I can afford to do that.

SCHUELKE: What is the most difficult thing about being Cary Grant, the movie star?

GRANT: I don’t consider it difficult being me. The only thing I wish—that we all wish—is that our faces were no longer part of our appearance in public. There’s a constant repetition of people approaching me—either for those idiotic things known as autographs or for something else. That’s the only thing I deplore about this particular business.

SCHUELKE: Do fans still approach you today?

GRANT: It happens, but not as much as it might to a Robert Redford or some younger, more popular star today. It gets to be a bore.

SCHUELKE: Have there been many interesting encounters with your fans?

GRANT: The people I’d most like to meet are the least likely to come up to me.

SCHUELKE: Are you accessible to your fans? Do you interact with them?

GRANT: I do not care or like to talk to [my fans]. I’m not rude. I try to be as gracious as I can when someone next to me at dinner wants to know how I feel about a leading lady. But I don’t answer letters to fans. I don’t answer anyone’s letters. I couldn’t possibly answer everybody. I can’t even attend to my own legal matters. I must receive two sacks of mail every day. So you can’t answer the people. You feel rather sorry you can’t, especially where there are children concerned, but it can’t be done.

SCHUELKE: Is it true that President Kennedy once telephoned you from the White House just to hear the sound of your voice?

GRANT: We all knew each other, just as we know our current president, who is a very dear and very friendly man. We [Reagan and Grant] are old friends.

SCHUELKE: Film students break your films apart and analyze them. Do you think scholars place too much emphasis on films that were made strictly for entertainment?

GRANT: Oh, yes. A film’s a film. As Hitch would say when someone would get all upset on the set, “Come on, fellas, relax—it’s only a movie.” Now, if you want to dissect it and tri-sect it and cut it up into little pieces, well, that’s up to you. We made them. We didn’t know their intentions half the time, except to amuse and attract people to the box office.

SCHUELKE: What are your memories of working with Alfred Hitchcock?

GRANT: I have only happy ones. They’re all vivid because they’re all interesting. It was a great joy to work with Hitch. He was an extraordinary man. I deplore these idiotic books written about him when the man can’t defend himself. Even if you defend yourself against that kind of literature, it gets you nowhere.

SCHUELKE: You worked with some of the most beloved leading ladies in film history. Who was the best actress with whom you worked?

GRANT: I’ve worked with many fine actresses. But in my opinion, the best actress I ever worked with was Grace Kelly. Ingrid [Bergman], Audrey [Hepburn] and Deborah Kerr were splendid, splendid actresses, but Grace was utterly relaxed—the most extraordinary actress ever. Her mind was razor-keen, but she was relaxed while she was doing it. I appreciated that. It’s not an easy profession, despite what most people think.

SCHUELKE: What it disappointing to you that Kelly gave up acting to marry Prince Rainier?

GRANT: As far as we were concerned, she was a lady, number one, which is rare in our business. Mostly we have manufactured ladies—with the exception of Ingrid, Deborah, and Audrey. Grace was of that ilk. She was incredibly good, a remarkable woman in every way. And when she quit, she quit because she wanted to.

SCHUELKE: How was it working with Katharine Hepburn?

GRANT: Marvelous. I worked with her about five times. One doesn’t do a thing more than once—unless you’re an idiot—that one doesn’t like.

SCHUELKE: In the 1950s, you announced that you were retiring from films. The retirement was short-lived, but what made you want to give up films at the height of your career?

GRANT: I was tired of making them.

SCHUELKE: How did your friends and colleagues react to your decision?

GRANT: People say all sorts of things. I gave it up because I got tired of doing it at that point in my life; I had no idea then whether I would resume my career or not. The last time I left, I knew I wouldn’t return to it. I enjoyed the profession very much. But I don’t miss it a bit.

SCHUELKE: Has anyone in the movie industry ever told you your work has influenced the films they’ve done?

GRANT: Everybody copies everybody else, if they think you’re doing something better than they. Athletes do that; that’s evident in the baseball scores and the improvement of the hitter today.

SCHUELKE: How do you respond to criticism that you never portrayed anyone but yourself in your films?

GRANT: Well, who else could I portray? I can’t portray Bing Crosby; I’m Cary Grant. I’m myself in a role. The most difficult thing is to be yourself—especially when you know it’s going to be seen immediately by 300 million people.

SCHUELKE: What about the people who say you should have expanded your repertoire to include more “character” roles?

GRANT: I don’t care what people say. I don’t take into consideration anything anyone says, including the critics. There’s no point. You’ve made the film, it’s done and if they want to criticize it, that’s up to them. I don’t pay attention to what anybody says —except perhaps the director, the producer and my fellow actors. But I’m not making films; I haven’t made a film in 20 years.

SCHUELKE: Do you think these people misinterpret what you were trying to do?

GRANT: I have no concern with what anyone else is thinking—I can’t affect it—or with what anybody else is saying anywhere in the world at any dinner table tonight. They may be discussing me or somebody else; I don’t care. I’ve nothing to do with it, and I can’t control it, so it doesn’t matter what people say.

SCHUELKE: Do you have a favorite film?

GRANT: Not really. I did them all for a purpose. Sometimes I hoped for better results; sometimes I was surprised at the results.

SCHUELKE: Why did you leave acting for the business world in the ’60s?

GRANT: Acting became tiresome for me. I had done it. I don’t know how much further I might have gone in it. I have no knowledge of that, of course. But I enjoyed going from where I started on to a different world, equally interesting—perhaps more so.

THIS INTERVIEW INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE JANUARY 1987 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.