New Again: Alain Resnais

From the emotional and physical wreckage of the American bombing of Hiroshima emerges a romance between a nameless French woman (referred to only as She) and Japanese man (He) in Alain Resnais’ 1959 masterpiece of Nouvelle Vague cinema, Hiroshima Mon Amour. The film’s screenplay, nominated for the Oscar in 1961, was written by Marguerite Duras and remains a cornerstone in the evolution of New Wave aesthetic and storytelling. Emmanuelle Riva (Amour) and Eiji Okada star as a French journalist and married Japanese architect who begin a fleeting affair. The dialogue takes the form of a faceless conversation between the two about memory and experience overlaid on a montage of images of their relationship and the ongoing devastation in Hiroshima.

A newly restored edition of Hiroshima Mon Amour will grace the screen at the New York Film Festival’s Revivals section this fall. Due to rights management, the film has not seen an American theatrical release in several decades, so this restoration brings the iconic work to a whole new generation of viewers. The festival begins September 27 and will act as a prelude to a longer run for the film at Lincoln Center beginning October 17.

While Resnais is perhaps best known for Hiroshima Mon Amour and the later work Last Year at Marienbad (1961), he also helmed 1977’s Providence, his first English-language film, which stars John Gielgud (Gandhi) and also features the late, great Elaine Stritch in a critically-praised performance as Helen Wiener. Tinkerbelle and Donald Lyons sat down with Resnais on behalf of Interview in April of that year for a bilingual conversation to discuss film critics, real estate, and mortality. —Katherine Cusumano

Alain Resnais: From Marienbad to Providence

By Tinkerbell and Donald Lyons

For the information of those who are into it and also for those who are not, Alain Resnais is a Gemini, having been born in Brittany on June 3, 1922. He made his first film at the age of 12. Of all his film achievements, Last Year at Marienbad is probably the most popular. It’s considered a venial sin by film buffs to not have seen it. Resnais’ first English-speaking film is the recently released Providence. Despite the fact that the shooting of Providence was not an easy chore for a French-speaking director with English-speaking actors—and in less time than a dog’s pregnancy (two months), the filming was completed—the movie emerged like a black orchid in a batch of daisies, startling and catching off-guard critics and audiences alike. But for those who don’t shock easily, it was immediately apparent that Providence is a top-quality production abundant in style, taste, candor, humor and riveting one-liners. David (Morgan) Mercer penned the screenplay.

Providence is a mind-twister of a film not recommended for those who choose not to think. It’s a surrealist story of a dying novelist’s fantasies and the essential sadism of artistic creation. John Gielgud, in by far his best screenwork, as the novelist, lies in bed in the small hours of the morning, killing his terminal pain with wine and suppositories, while trying to conceive and piece together fragments of his last creative work. And if the plot is not unique enough, Providence is also a bizarre black comedy.

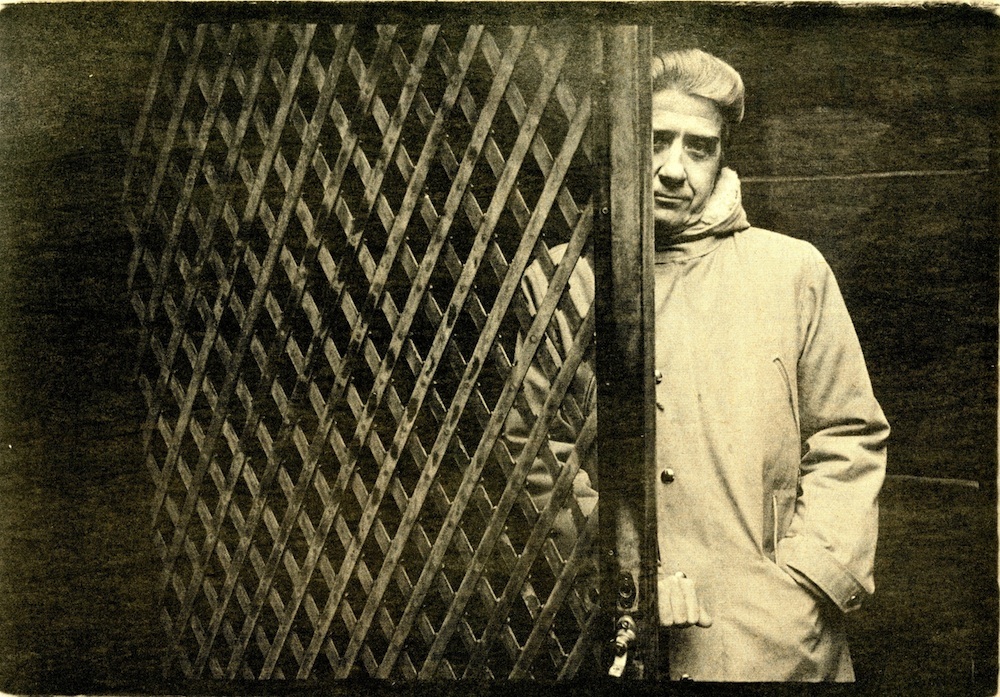

Although we addressed our queries to Alain in English, he answered us in flowing, glowing French. It soon became evident that the man is also abundant with off-screen surprises. His presence graced his Central Park South hotel suite, more than it nestled or took up space. His belongings and books were so tidily arranged, they did not betray the obvious state of temporary residence, so dead a give-away of hotel rooms. And Resnais himself, his high forehead framed by a graying, swept-back pompadour reminiscent of Cocteau, sat attentive and demure while his directorial pearls of wisdom poured from his mouth like choice syrupy liqueur. His elongated lower limbs crossed like entwined vines and his tapered fingers stretched as though reaching for the invisible. It struck us as keenly coincidental that even his presence appeared well-edited!

INTERVIEW: When did you go from watching films to making them?

ALAIN RESNAIS: When I was 12 I made some little films with my friends. I tried to make gangster films, like Fantomas, but I remember being very disappointed with them. They weren’t frightening at all. I’m sure they’d be very funny now.

INTERVIEW: Are these films lost?

RESNAIS: Oh, maybe not. Maybe they’re in some cave. But they are without interest. They do not betray my future.

INTERVIEW: Our French isn’t that good. Would you mind sticking to “yes” or “no” answers? I’ve seen Providence twice because I enjoyed it so much the first time, because it’s one of those “ya gotta see it more than once films,” and also to qualify my own favorable feelings about it. I was surprised at the negative reactions of some critics. The second time around, I still disagreed with the critics who claimed it was a “put on,” etc.

RESNAIS: It’s kind of you to express that, but for me an unfavorable initial reaction happens fairly often. For some reason the more time that elapses after the film opens, the more favorable the reviews become.

INTERVIEW: That’s what happened with Fellini.

RESNAIS: My films seem to be better understood and better received by the monthly publications. On television the first reactions are usually unfavorable.

INTERVIEW: Some people call Providence pretentious. Why, do you think?

RESNAIS: Obviously I was disappointed that people felt it was pretentious. We didn’t set out to make a pretentious film. We thought it was a black comedy—but we didn’t think the critics would interpret this as pretention.

INTERVIEW: Could the fact that you incorporated so much taste and style in the décor and settings have anything to do with it? Also, is your stylish type of approach part of your concept of what makes good cinema?

RESNAIS: I can’t see any reason why a film shouldn’t be stylized and visually beautiful. I don’t think a beautiful set is pretentious. If one were to create a sculpture he would want to make the form of the sculpture as beautiful as possible, and I don’t see how it could possibly be considered wrong to have the same approach in the creation of a film. There are, of course, various ways to approach a production, but this is the way I chose to do it. A viewer as opposed to a filmmaker might see it differently. But I’m extremely comfortable with my style.

INTERVIEW: A lot of people with style are. Were John Gielgud, Ellen Burstyn, and Dirk Bogarde your first choices for their roles?

RESNAIS: Yes. I was very lucky.

INTERVIEW: So were they.

RESNAIS: All the people who appear in the film are the actors I had requested. This was a great accomplishment on the part of the producers because the actors lived scattered all over the world and had various commitments.

INTERVIEW: The houses that you selected for the film were splendid. Who actually owns the house where Burstyn and Bogarde lived, and is he single?

RESNAIS: That house was a studio set.

INTERVIEW: Are you absolutely positive? What about the house where the elder Langham (John Gielgud) resided—Providence?

RESNAIS: John Gielgud’s house was a house owned by Americans in France who hired an American architect to build it for them. However, this was not my first choice for the film. Originally I had picked a house that I had seen in New England, but it was too costly to come to the U.S. to film, so we stayed in France and that mansion was the closest thing we could find to what we wanted. The light was French light, but the house, even though it was located in France, was an American house.

INTERVIEW: Another of the film’s beauties was the music.

RESNAIS: It’s very … sticky. Miklos Rozsa and I decided on a music of sleep, a music of sleep and insomnia at the same time. A music of three or five o’clock in the morning.

INTERVIEW: They should call it Music to Drink White Wine By.

RESNAIS: Yes, exactly. Alcoholic music. After all, Miklos Rosza scored Lost Weekend.

INTERVIEW: Was there any symbolism behind the hairy wolfmen?

RESNAIS: The hairy men were not symbols to me. I don’t like symbols. This is just one of the fragments of a sick, unhappy, and dying man’s reverie. These images come to a man in the throws of creativity who is drinking heavily to drown out his sorrow and pain. He is also taking drugs, which have an influence on his imagination. These fantasies are occurring during the mental state when one is between dreaming and sleeping. In this dreamlike state a person is sometimes startled or surprised by what he sees or hears. For example, this dying man is seeing men who resemble foxes and dogs, and for him these images are very enigmatic. These could be images of the aging process or death as after death one’s hair and fingernails continue to grow.

INTERVIEW: How did your film crew react to the shooting of the cadaver’s dissection?

RESNAIS: It was a rather uncomfortable situation, and I shot it with as small a crew as possible.

INTERVIEW: Have you had a lot of close contact with the dying, or was the projection of a creative man’s painful death strictly David Mercer’s interpretation?

RESNAIS: I wanted to project an understanding, sympathy, and empathy for the terror that comes with the sadness and depression—not necessarily with dying but with the disintegration of the body and the onslaught of old age. We can all see it in small things, like having to wear glasses. Why, why, why? we say. My mind hasn’t changed, my desires haven’t changed.

INTERVIEW: How do you feel about dying?

RESNAIS: We should all die with a sharp, brusque heart attack.

INTERVIEW: That’s how a cousin of mine died. He sat up and said, “This is it.” And it was.

RESNAIS: My father was lucky like that. One day he went hunting. He had a good day, he killed a lot of game, he was with his best friends. He said, “Ah, I’m still a good hunter.” Then he said, “I don’t feel well,” and in 30 seconds it was all over.

THIS ARTICLE INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE APRIL 1977 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.