Nate Parker’s Future Past

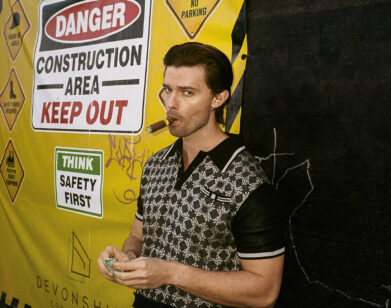

ABOVE: (LEFT TO RIGHT) MAX GREENFIELD, NATE PARKER, MAGGIE GRACE, JASON RITTER, AUBREY PLAZA, MAX MINGHELLA, AND JANE LEVY IN ABOUT ALEX. PHOTO COURTESY OF JAMI SAUNDERS/FOOTPRINT FEATURES.

It is a busy week for Nate Parker. The 34-year-old actor has two very different films currently screening at the Tribeca Film Festival: Every Secret Thing, adapted by Nicole Holofcener and directed by documentary filmmaker Amy Berg, and About Alex by new writer-director Jesse Zwick. Co-starring Aubrey Plaza, Max Minghella, Jason Ritter, Max Greenfield, Maggie Grace, and Jane Levy, About Alex is a bittersweet reunion film heavily indebted to The Big Chill. When failed actor Alex (Ritter) attempts suicide, his five college best friends try to rally around him in his father’s dilapidated country home. It’s been a decade since they left college (Yale, to be specific), but each relationship still has its own distinct emotional baggage—a not-so-hidden undercurrent of envy, desire, or hurt. Parker plays writer Ben, the anchor of the group who always seemed just a little bit smarter, shinier, luckier, and more talented than his friends. In reality, however, Ben is dealing writer’s block and imposter syndrome—the feeling that he’ll never be able to live up to the expectations of those who claim to love him.

This summer Parker, whose past credits include The Great Debaters (2007), Ain’t Them Bodies Saints (2013), and Arbitrage (2012), will direct his first feature. “The one thing I love about acting,” he explains, “is that you can sit on a bench in Central Park and learn enough to develop a character and allow that person to speak and be authentic. I think the director does the same thing,” he continues. “The director can take in this hotel and the colors and create a vision that will go into a film.”

EMMA BROWN: Did you originally audition for the role of Ben in About Alex?

NATE PARKER: I did not. I got a call from my team saying that a director wanted to meet me named Jesse Zwick. And I said, “Jesse Zwick, Jesse Zwick…. Is he related to [Oscar-winning director] Ed Zwick?” And they were like, “Yes, it’s his son.” I thought, “If that fruit doesn’t fall far from the tree, whatever it is, it could be interesting.” I was in New York doing a film, and they said that the director had seen a film I’d done called Arbitrage and wanted to talk. We met in a café with Adam [Saunders], the producer. And we just hit it off. An hour later, we were like, “We’re going to do this thing together no matter what. We’re going to figure it out.” Just to hear Jesse speak so passionately about something—a project that meant so much to him—made it mean a lot to me. Reading the script, [it was] something I responded to right away—something that really dealt with the human condition, the intimacy of relationships and how a lot of it is going to be farmed out to social media channels. It made me want to see if I could embody a voice that would speak to it and create a filmic discourse. So I didn’t have to audition, per se, but there was a meeting where we both realize we were on the same page.

BROWN: Were you always going to play Ben as opposed to one of the other characters?

PARKER: From what I know—unless Jesse had other ideas. He was open. Far too often scripts are being written with race in mind, but the subject matter doesn’t lend itself to any conversation on race. I applaud Jesse for having the courage to say, this is just a story about friends, and they could be anyone. There’s no specific color that forces a relationship to be discussed in any other manner. Here’s an African-American guy with a blonde, blue-eyed girl, and you buy it because we did the work, we rehearsed, and we genuinely cared about each other.

BROWN: Well, you would buy it in any of the roles because, as you said, it’s just a story about friends.

PARKER: Exactly. I think Jesse is part of a new generation of director, because we’d be kidding ourselves if we did not acknowledge that there is this unsaid rule that the hero looks a certain way. But a lot of those old ideas are dying with the people who created them, and there’s this new generation of filmmaker that’s saying, “We’re in this together, these are issues that we all deal with, let’s just present issues to screen without bias and figure out what the audience has to say about them.” And that’s what this film is about, I think.

BROWN: Is there one filmmaker, aside from Jesse, whom you particularly admire from this new generation?

PARKER: Yeah. There’s a cinematographer called Bradford Young, who I adore. There’s a director, David Lowery, I worked with him on Ain’t Them Bodies Saints. I’m directing a film in the fall, so he’s become very much a mentor for me, or a tutor, so to speak. He was working with me on my script—just the prep work that goes into directing, and the intimacy between director and actor, and how to really pull the most out of your cast. But I’m very excited about David. And he’s young. He’s, like, my age. Or younger than me. And I’m very excited about his DP, Bradford Young, and it’s looking like he’ll be working on my film with me. I’m very excited about Ryan Coogler, who did Fruitvale Station—just his integrity, his intelligence, and his perspective on film, and what he’s going to be doing. I think it’s like the ’60s—we’re going to see another revolution in film where these new filmmakers stand up and take ownership of what film is and mould it into what they want.

BROWN: One question people seem to ask actors a lot is, “What was it like working with a first time director?” Is it really regarded as this big challenge in the film world? Is there really this stigma attached to working with new directors?

PARKER: Either you have vision or you don’t. The way sets are designed, if you get financing for a film, you hire a line producer, [who] will hire a team that you need to achieve what you need to achieve. You hire the right DP, who will help you pick the shots that you need to get in the can for the editor. The editor will create a story that is hopefully congruent with your vision, and then you have a product. If a director, I believe, has vision and knows so clearly what they want, then you can have a film that can perform. Whereas you can have done 50 movies, but if you’re unsure this time, your movie may not turn out. So I think the only stigma there is the one that people on the outside put on the director. I think it takes a lot of courage to be able to direct a film. If you have that courage and that vision together, and you pick the cast that you believe will achieve your vision, you win.

BROWN: Have you ever been involved in something where you felt like the people in charge weren’t fully committed to it—didn’t have a clear vision?

PARKER: Yes. I’ve been in a situation where the preparation did not reach the level of expectation, and a lot of that can come from inexperience. [But] I didn’t experience that at all with Jesse, I didn’t experience it with David Lowery, I didn’t experience it with [Arbitrage director] Nick Jarecki, who were all first-time feature directors. But I’ve been on one set in particular where I was dealing with a director that just didn’t really have a concept or understanding of collaboration. Sometimes little things can prolong an experience in a way that you run over budget. It’s very scientific; a lot of people don’t understand the science that goes behind making a film. But I’ve been blessed to have almost all positive experiences, and in the end it almost always works out. The good thing about a film, or at least the films I’ve been a part of, is, no matter what happens in the end, you do the premiere and everyone’s excited. You don’t remember the rough times. But that’s why you have a team, so that when one part falters, the rest of the package steps up and makes sure it works it out.

BROWN: Can actors and directors be friends during filming, or does there need to be a certain divide to maintain respect or authority?

PARKER: There has to be respect, of course, but friendship is deeper than what happens on set. If you’re going to be friends with a director, then that seed was probably planted before the camera went up, and then it will grow, more so, after the filming is over. The friendship is there, but it doesn’t take precedence over the task at hand.

BROWN: In the film, Alex and Ben have a very complex, slightly ambiguous relationship. Alex clearly looks up to Ben, and loves Ben, but you’re not really sure to what extent. Did you talk about the relationship while shooting?

PARKER: We did. Self-esteem and identity are very fragile things. I think a lot of times, those are the motivations for why people do take their own lives—not being seen, not being recognized, not being loved, not feeling supported, not feeling understood. Ben is someone who, not only has seen Alex, but sees everyone. A lot of times, you find yourself in a situation where you see someone and you’re like, “I wish I was more like that person,” or “that person is someone I want in my life,” or “if I could just have that person around, I’ll be a better person—I’ll be more successful, I’ll experience life in a more abundant way.” And that’s what their relationship is more about. I think it’s platonic, it’s a brotherly relationship, but, at the same time, it’s envy, and I don’t think it’s a sexual lust, but it’s a lust—a desperate desire to be a part of whatever it is that that guy is doing. [Ben] wrote this wonderful thing, he got all this praise, he’s like the father of his friends—with his girlfriend, they’re the mother and father [of the group]. I think a lot of relationships are like that. [But] it brings you back to, like, Single White Female. Sometimes that relationship can go sour where a person can become so desperate that they take desperate measures to achieve the goals they have for that relationship. And I applaud Jesse for going there, because a lot of times it’s an awkward feeling; it’s a tough place to go. And to do it in a way that’s authentic without really passing judgment on it. And to let it be what it is without having to define it.

BROWN: I feel like that complicated mix of admiration, love, and jealousy is often explored in coming-of-age films about teenagers, but not often in terms of adults.

PARKER: And friendships. How many films are there about friendships between teenagers? And how many projects are there dealing with friendships among adults? True friendships—really dealing with the intimacy behind what happened then, and how long you’ve known each other, and the wounds that haven’t healed. That’s what this film is about; there are so many deep wounds that you kind of glaze over. It’s like when someone does something to hurt you in your life, and it’s never been addressed. Ten years from that moment you still remember, and it still affects you, but you feel ridiculous for bringing it up because it was so long ago. But it affects your walk and your friendship every day until there’s an honest confrontation.

BROWN: Can a wound like that be really be resolved by confronting someone 10 years after the fact?

PARKER: It’s the only way. It’s therapy. They say true healing requires honest confrontation, and that can be seen on a macro scale with America and the things that have been swept under the rug, whether it be with the native Americans or slavery, or whatever holocaust that’s happened on this soil. Then it can happen on a very intimate level with a father and a son. Someone not being there, and then they’re there later and you don’t want to bring up the fact that they weren’t there before—the things you had to deal with when they weren’t around. You’re so happy that they are there that you don’t want to push them away. This is the psychosis of being a human being—the things that we deal with on a day-to-day basis that make us who we are and that sometimes we have to get on the couch and talk out.

BROWN: David Lowery said that he wanted Ain’t Them Bodies Saints to look as if it had been shot through a burlap sack, which is such an evocative way to put it. Do you have an image of how you want your film to look like?

PARKER: Yes. I don’t have a saying as cool as that one, maybe if you ask me tomorrow, but I want you to feel every emotion you see. I want you to feel heat when it’s hot, I want you to feel cold when it’s cold, I want you to feel pain when there’s pain, I want to make you feel laughter when it’s time to laugh. And I want you to feel it as if it’s present. It’s set in 1831, but the issues are still so present, and I think that if you watch this film, and you’re able to go have dinner and talk about what happened on the news, then I’ve failed. My only goal with this is to create a discourse that will promote healing in our community and in our country. Because we are a conglomerate of our experiences—you take away any experience and you take away a piece of identity. You take away a piece of identity and we don’t really know who we are. If we don’t know who we are, it’s going to be really hard for to interact in a way that’s productive as people, and we’ll still have these issues moving forward, whether it be race, or whether it be sexism—sexism is something that I also deal with in this film as well, because in 1831, women had no rights. They had no property; they held no deeds. As a filmmaker I want to inspire discourse about where we are—honestly—and where we’re going.

BROWN: Are you allowed to tell me what your film is about?

PARKER: Oh, yeah. It’s about Nat Turner, who led the most successful slave revolt in American history. It’s called A Birth of a Nation, ironically, but very much by design. It’s my life’s work. I’ve been working on this script for eight years and finally it’s coming to fruition. We’re shooting in August in Louisiana. I’m probably more excited about it than any piece of work I’ve done so far.

BROWN: Will you star in it as well?

PARKER: I’m going to star and direct, and I wrote it.

BROWN: Will you edit it?

PARKER: I believe in hiring people to do their jobs. I want to hire an editor—and I’m meeting with editors next week—that has a perspective, that understands the material, and that understands the human condition. They say you make a movie three times: when you write it, when you direct it, and when you edit it. So I have three shots to get it right! The script is solid, so I think it’s okay there, and I’m working on a cast that is strong and elegant and layered and troubled and harrowing and beautiful, and we’ll see where we lie. But my goal as an artist is to achieve the next level of expression. When an artist becomes complacent, he dies.

ABOUT ALEX AND EVERY SECRET THING ARE CURRENTLY SCREENING AT THE TRIBECA FILM FESTIVAL