Mike Leigh, Unscripted

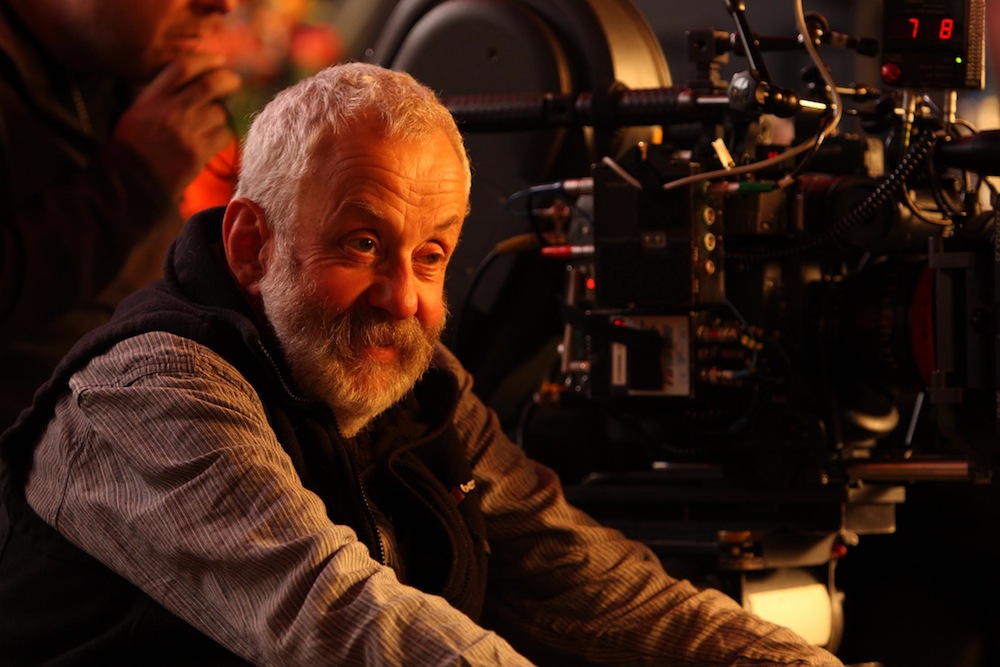

ABOVE: MIKE LEIGH ON THE SET OF MR. TURNER

Mike Leigh doesn’t make films about extraordinary people. There have been a few exceptions: in 1998 he directed Topsy-Turvy, a film about Gilbert and Sullivan, the 18th-century opera duo behind The Mikado and The Pirates of Penzance; in 2005 his film Vera Drake, about a back-street abortionist in the 1950s, was nominated for three Academy Awards. But, for the most part, the British director “likes to look at the lives of just people. I think everyone’s life is interesting,” he continues.

Mr. Turner, Leigh’s newest film starring Timothy Spall, might seem like another exception: J.M.W. Turner is perhaps the most famous and prolific 19th-century British artist, and he was recognized for his work during his lifetime. “It’s a question of subverting an icon,” Leigh explains. “This is a great painter. We accept that that is what it’s about, but let’s actually look at him as a real person. Let’s look at him going through what we all go through in one way or another. If he’s a great painter, let’s see him roll up his sleeves and go through the down and dirty business of doing it.”

The film begins in 1825 when Turner is already an established painter, and continues for the 26 years until his death in 1851. Played by Timothy Spall, Leigh’s longtime collaborator, Turner is gruff (there are probably more grunts than words and he occasionally spits on his work to help mix the paint), prescient (Leigh portrays him as the father of the Impressionists), and surprisingly funny (particularly in his interactions with John Constable and his other peers at the Royal Academy). He can be extremely compassionate and affectionate (to his father and his mistress Mrs. Booth), and extremely cold and unforgiving (to his children and his longtime housekeeper).

“I’ve never written a script in my life,” Leigh emphasizes. Instead, he begins each new project by working one-on-one with his actors before bringing them all together. “For me, the job of making a film, whatever the film is, is a journey of discovery and a journey of education.”

EMMA BROWN: I read that you grew up thinking of Turner and Constable as “biscuit box” painters.

MIKE LEIGH: Well, that’s sort of Chinese whispers. What I actually said was that I hardly grew up thinking of him at all. If I thought about him at all, I probably thought that, because I don’t really think he was on my radar until I was an art student. We were looking at figurative art and suddenly you realized that Turner was very special—different.

BROWN: Did you have that revelation about Constable as well?

LEIGH: No. Never. [laughs] He’s a great painter as far as it goes, but I don’t think he’s remotely interesting. Not really. It’s very pretty and it’s very thorough, but it’s not evocative, it’s not dramatic, it doesn’t do what Beethoven does—it doesn’t shake you down to the roots of your soul, which Turner does. Constable is just very nice, basically. And moving on to personality, Constable was a very dull character. People keep saying, “Are you going to make a movie about Constable?” No. [laughs] Plainly Constable had no sense of humor, which doesn’t surprise me.

BROWN: I know Mr. Turner is a film you’ve been considering for a long time. At what point did Timothy Spall come into the process?

LEIGH: Some way into the process. As soon as I started thinking, “Yes, but who could play Turner?” Tim seemed like the best idea, really. In fact the only idea. Why? Because he’s a great character actor, because he’s a Londoner, because he comes from a working class background. I knew he could get the grain of Turner in some way. Also, I think it’s important, he’s read a lot of Dickens. He’s very good at 19th century—he did a very good 19th-century character in Topsy-Turvy, with which I presume you are familiar. Also, I knew he had some healthy amateur pretensions to painting and drawing. He went off to lessons for two years.

BROWN: Was that your idea?

LEIGH: Our idea. It seems obvious. If you’re going to play Turner in a movie about Turner, it seems like a good idea to learn about painting.

BROWN: What made you focus on Turner’s later period?

LEIGH: Well, you could make a biopic I suppose. You could find a fat baby and a little fat boy who can draw and looks like Tim Spall and a fat teenager, and drag out all the events—go through the Napoleonic Wars and the rest of it. I felt that the 26-year span of the film, which is rather longer than I normally deal with in my films, would be quite enough to get our teeth into. All of the interesting things that happen to him [happen during that time period]—especially and not least with his work becoming really radical and misunderstood by people, but also with the death of his father and the relationship with Mrs. Booth. Any backstory I wanted to feed into it could be fed into it.

BROWN: Turner bequeathed all of his work to the nation. Is that something you think modern artists should learn from?

LEIGH: You have to remember that at that time there were no public galleries. The only publicly-owned art gallery in the world was the Louvre in Paris, and that was full of stuff that Napoleon had looted and a result of the Napoleonic Wars. All paintings were in private collections. In Turner’s case, the only way people knew his work—unless they’d been lucky enough to go to London and see the stuff the Royal Academy Exhibition, which most people wouldn’t have done—was in bad, black and white reproductions, which were then circulated. Turner’s vision was to have public art galleries for free, which was very radical and remains radical in most places. London is one of the only places where you can go into a public art gallery for nothing, really. It took from 1851, when he died, to 1947 to sort out [all his work], partly because of the Wars. Then it went mostly in the Tate, and some of it in the National Gallery and the British Museum. But when he refuses to sell the stuff, that’s what it’s about, the idea that the public should be able to see the work. So to answer your question, should all artists do that, well, the point is—I’m talking from a British perspective, obviously—I think it’s good for artists to leave their works for the public to see, but it’s also, now, the responsibility of public collections to purchase the works of artists so that artists can feed their families during their lives and the public can see the work.

BROWN: I read that you tried to match the cadence of 19th-century speech.

LEIGH: Oh, we did. But in a way that’s easy—easier than a lot of other things. It’s not a question of matching the cadences— though that’s an interesting way to put it—it’s a question of really getting the language and the principle of the language and the words themselves and the expressions and the phrases into your bloodstream. I’m quite good at that. That’s something that comes relatively easily.

I realized only recently that Turner died only 92 years before I was born. That’s the equivalent of 1922, which was quite recent, actually. It made me realize that the 19th century, the mid-19th century, hangs in the recent received collective memory. Marion Bailey, when she was researching Mrs. Booth, found some recordings. She wanted to know how people talked down in Margate and that part of Kent in the period; now they talk a very contemporary, outer-London English. She went to the British Library and found recordings of guys from that area—very old men— made in 1951. She calculated that these guys really would have been children around the time that her character died. So she found it very useful. And there were all sorts of language and nuances in the way they were talking and the words they were using which were useful in her characterization. Now, if I was to make a film set in the 12th century, I don’t know how the hell I would commence the business of how people talked. But the mid-19th century is actually not so long ago. It’s more contemporary than we think.

BROWN: Would you make a film set in the 12th century?

LEIGH: No. [laughs]

BROWN: With a biographical film, what is the most important thing—to be true to the events or true to the experiences?

LEIGH: It’s important to be true to the events, but the most important thing is to get to the essence of the experience. Not to be bogged down in an academic way by a notion of the truth. First of all, the truth is an illusive and spurious concept. Say, for example, the scene where Turner puts the blob on his painting. We know that happened. We know that what we’ve constructed, in principle, is apparently what happened; there’s nothing about the way we approached it which, in any way, was irresponsible about trying to be truthful to what we gathered happened on that occasion in 1832. But, if you got into a time machine and went back to that actual event, I’m sure that what you would discover would bear absolutely no resemblance to what’s in the film. All research, anything that anyone or you or I read about something that happened—including something you might read in the newspaper about what happened yesterday in Venezuela—then becomes something in your head. The thing that actually happened isn’t in your head; it’s your notion of. So the notion of trying to be true is a complicated one. What drove us in the spirit in which this film was made, was to attempt to be truthful to a sense of something, to be consciously strict about certain events as far as we could, and to be relaxed about [other things]. Certain things happened in the film sooner than they actually happened. For example, Turner never went down to Margate [where he] met Mrs. Booth until after his father had died. That’s how we filmed it, but when we looked at the construction of the film, we realized that if he went down there before it would structurally be better. And I didn’t feel, “Well, this is absolutely out of the question because it didn’t happen” because, so what? The film itself is a distillation. You do it in a relaxed and sophisticated way but with a great commitment to being accurate in order to create the illusion of a very, very real world. I hate period films—and there are plenty of them—where they say, “Let’s not do contemporary language because the audience won’t understand it;” “let’s not make the girls wear corsets, because it’s not sexy” and all that sort of thing. Gradually it disintegrates into a no man’s land: you don’t really believe it’s a period scene and it doesn’t feel like it’s now because it’s not now. You don’t feel it’s quite real and you don’t believe in it. I hope what we’ve done is to create a film where you really do believe in it—because the detail is all there—but we’ve been sophisticated with how to use the detail, how to organize.

MR. TURNER IS NOW OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE.