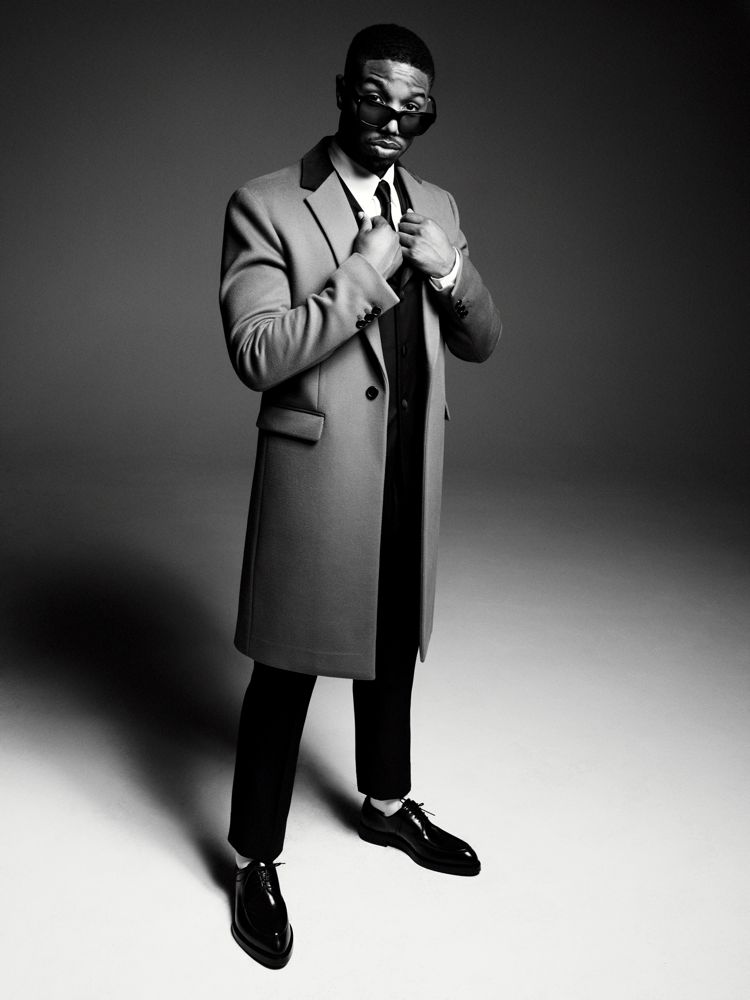

Michael B. Jordan

Oscar Grant was somebody who looked like me, could easily have been me. Michael B. Jordan

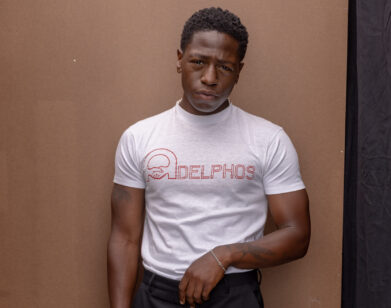

When your name is Michael Jordan, people almost instinctively have expectations. Until recently, though, 26-year-old Michael B. Jordan, the actor, was among television’s best-kept secrets—and, interestingly, one who made a name for himself with his work in an athletic milieu, albeit not a court but a gridiron. The Newark, New Jersey, native began his small-screen career at the age of 12, appearing on an early episode of The Sopranos and in a recurring role on Cosby. He earned his stripes during a three-year run on the daytime soap All My Children, but his bona fides arrived via roles on two of the most highly acclaimed series of the last decade, playing ill-fated corner boy Wallace on the first season of the HBO drama The Wire and promising QB Vince Howard on the cultishly revered Friday Night Lights.

This is the year, though, that Jordan becomes a movie star with his top-billing turn in Ryan Coogler’s Fruitvale Station. Based on a true story, the film recounts the last day in the life of Oscar Grant (Jordan), an unarmed 22-year-old who was shot dead by a transit police officer in the early hours of New Year’s Day in 2009 at the Fruitvale stop on the Oakland BART. Grant’s death reverberated throughout both his community and the nation, and Jordan’s portrayal is nuanced, complex, and affecting. If Coogler’s vision of Grant seems tailor-made for Jordan, then it’s with good reason: He wrote the screenplay with Jordan in mind. The film, which premiered this past January at Sundance, has already met with widespread acclaim, and ever-growing murmurs of Oscar contention have even begun to surface.

In the meantime, Jordan has kept himself busy with a steady raft of film work. In addition to Fruitvale Station, he appeared last year in the sci-fi flick Chronicle, and just finished shooting Are We Officially Dating? with Zac Efron, Miles Teller, and Imogen Poots.

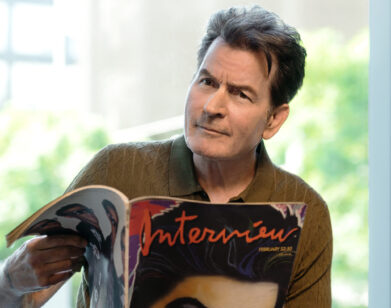

Forest Whitaker, who, as a producer, helped bring Fruitvale Station to the screen, recently spoke with Jordan, who was at home in Los Angeles.

MICHAEL B. JORDAN: How you doin’ in Hollywood?

FOREST WHITAKER: I’m well. I’m in New Mexico, actually.

JORDAN: Oh, word? Okay, cool.

WHITAKER: I’m just excited, man. It’s a great time as an artist, you know?

JORDAN: It’s mind-blowing, man. Like, every day is something that I never would’ve expected, so now it’s just trying to own it. Owning it and looking forward to what’s about to happen as far as Cannes and everything else, and the movie release. I’m just excited to be along for the ride with you guys, man. It’s pretty special.

WHITAKER: I just was thinking about it because the work you and Ryan [Coogler] are doing is, like, the voice of today. But I started looking back at some of the stuff you’ve done, and I realized you’ve been doing it for so long. I mean, it seems like over half your life.

JORDAN: When people say, “How was it being a child actor?” I’m like, “Damn, I guess I was a child actor.” I started at 12, but didn’t really know what I was doing at the moment and didn’t really realize the foundation that I was laying down. And then working with such veterans and such prestigious shows at such a young age, I matured very quickly … Working with Bill Cosby and David Simon and the folks over at HBO with The Wire. So it doesn’t seem like it, but I guess I’ve been doing it for, like, 13 years. Man, that’s a long time.

WHITAKER: When did you decide that you loved it?

JORDAN: The first time I lost myself in a character, in a role—that was on The Wire. You know Andre Royo, who played Bubbles? There was a scene where Wallace first started snorting stuff as a young drug dealer, and I’m just mimicking. I mean, I’m from northern Jersey. I’ve seen people sell dope before, but when it comes to that stuff, I had nothing to pull from whatsoever, so he kind of pulled me to the side and coached me through it—you know, the feeling that you get from the top of your head all the way down to your toes, and he really talked to me about losing yourself in that moment: “Forget the cameras are here. Just block all that stuff out and really focus in on this moment and what you’re going through and why you’re doing it. What forced you to the point to try something that you’ve never tried before?” And, at 15, it was the first time anybody had ever pulled me to the side and coached me through it in a one-on-one way. And I remember just losing myself, man—I checked out. And it took me some time to kind of get out of it. I was, like, sad the next day, and I didn’t know why I was feeling that way. So Andre, again, pulled me aside and helped me get back from it. And I was like, “Wow, that’s a crazy feeling.” And I got excited. I was all, “Oh, man, I want to do that again! I got to somehow get back to that place again.” And I think from that point forward, I’ve just been trying to find my moments and these roles where I lose myself and really dive in it.

WHITAKER: So that’s your process—to find a way to lose yourself?

JORDAN: Yeah. You know how it is sometimes, when a role doesn’t require as much of a dive in? It’s not easy, but it’s, like, cool, I don’t have to emotionally take myself all the way there because it’s right there. With television, it’s different because you live with these characters for an extended period of time. It’s a slow-burning art. I’ve learned from film that you really have time to get into this one specific place or this one specific moment in time, and you can really dive into it because you don’t have to go back to that place again. So I guess my process is to make it as real as possible, to try to make it make sense to me and for that character. It’s letting go and being completely vulnerable and just really not caring, just no self-awareness.

WHITAKER: Was there another part like that, where you were chasing that nirvana that you’re talking about, that space of magic?

JORDAN: Honestly, it’s happened maybe only three or four times. It was Wallace on The Wire, Vince on Friday Night Lights, Alex on Parenthood, and then Fruitvale Station was the last time where I really had to dive in.

WHITAKER: I know that Ryan wrote Fruitvale Station with you in mind. How did that make you feel?

JORDAN: It’s still shocking to hear people applaud my work. So when Ryan told me that, I was like, “Oh, man. Really?” I just felt honored and I felt a sense of responsibility and a little bit of added pressure. I wanted to make sure I lived up to those expectations he had for me. So then I felt excited to go out there and play that role, because I remember when it all happened. I felt helpless and frustrated and angry and pissed off and just an array of emotions. Oscar Grant was somebody who looked like me, could easily have been me. I’m from Newark, New Jersey, so we come from the same type of environment. I used to take the PATH train from Newark to the city all the time and go to all these different functions where there are cops, like the West Indian Day Parade, where people are drinking and having a good time, and where altercations are happening all over the place. I could’ve just as easily been in that situation. And feeling like you can’t do anything to change it is, like, one of the most helpless feelings ever. So when I had an opportunity to say something through my work as an artist, I could actually give an opinion … Because sometimes as an actor it’s kind of hard to have a real opinion when it comes to controversial material like this—things you say are held against you or your words can get twisted around. So for me to kind of step away, outside of Mike, and be like, “Okay, this is what we’re doing,” was a relief.

WHITAKER: I remember being in the office and seeing you and Ryan talking in the very beginning—there was a partnership, a relationship that was forming. Did you feel that from the beginning?

JORDAN: Yeah, man. As soon as I talked to him, really. We just started rambling on about the books we like and the filmmakers we look up to and the types of movies that inspire us. We had very similar tastes, especially in music. And during the whole process, Ryan was so giving. He puts himself last in every situation, and that’s a quality you don’t see that often. I felt like this is a friendship and a camaraderie and a partnership that’s going to go on, hopefully, for the rest of our careers.

WHITAKER: I know that for you and Ryan, it was so important to be accurate. It’s a different thing when you play a real character. What’d you do to get it there?

JORDAN: Well, there was no audio and no video of Oscar—there was nothing for me to go off of. It was just Oscar Grant, 22 years of age, African-American, Bay Area resident, for the most part. And I remember you telling me, “Don’t imitate. You represent him—be a representation of who Oscar was.” And that changed my whole angle on it. Basically, I had to learn who Oscar was through all the people who knew him best: his best friends who were with him that night; his daughter, Tatiana; his mother, Wanda; and Sophina [Oscar’s girlfriend and Tatiana’s mother]. The added pressure was not letting them down because they knew him so well. They’re gonna be the most critical, so that’s why at the premiere it meant so much to me for his aunt to say that there were certain things in the movie where she couldn’t tell the difference between Oscar and myself.

WHITAKER: I remember I was overseas and I had to show The Last King of Scotland [2006] to a general who knew Idi Amin. It was the first time that I really felt trapped. The president [of Uganda, Yoweri Museveni] was there, the general was there—they both had fought against this person whom I was portraying. I was feeling stressed. What were you feeling at the premiere with the people who knew Oscar?

JORDAN: I was nervous that when they saw the movie, they would just see Mike. Like, “Did I lose myself on camera? Did I pull it off?” I was very insecure, not knowing how it was gonna play or how it would be received. But to stand up there on stage afterward with everybody and with you guys, it also made me feel like I wasn’t alone. We went through war in the Bay together, so I felt very close to the people around me, and they helped my anxiety, man.

WHITAKER: I remember different people from the audience got up and they were crying. Were you always conscious of the fact that this was a story that crosses all barriers? Or was it just the character that was in your mind originally?

JORDAN: Just the character. I know exactly what you’re talking about. Me and Ryan talked about the message and why he wanted to hold the mirror up to America—for us all to really look at ourselves and how we treat people and how we treat one another. We wanted to give Oscar some of his humanity back. And at the time I was just thinking about the character. When I started hearing people saying how the movie touched them, I looked at who was saying it: It was, you know, a middle-aged white lady or an older white man, and then an Asian man, and then this black guy, and then this other black guy, and then this white girl, white guy … Everybody is emotionally affected by what they just saw and they don’t really know how to express themselves completely because they’re questioning certain things that they might have felt in their hearts for a really long time. It makes them question their outlook on certain things. And then it started to kick in … When I hear the same comments over and over again from different walks of life, it makes me feel like the message is not about race, it’s not about where you’re from—it’s about how we treat people. It’s about, regardless of what you’ve done in the past, you can make good choices moving forward, and I think it’s about trying. Oscar was a person who was trying. But I don’t think the message was at the forefront of my brain at all; it was honestly just being true to who he was. And then everything else that follows—that’s just the icing on the cake.

FOREST WHITAKER IS AN ACADEMY AWARD-WINNING ACTOR, DIRECTOR, AND PRODUCER AND THE FOUNDER OF PEACEEARTH. HIS LATEST FILM IS THE BUTLER.