in conversation

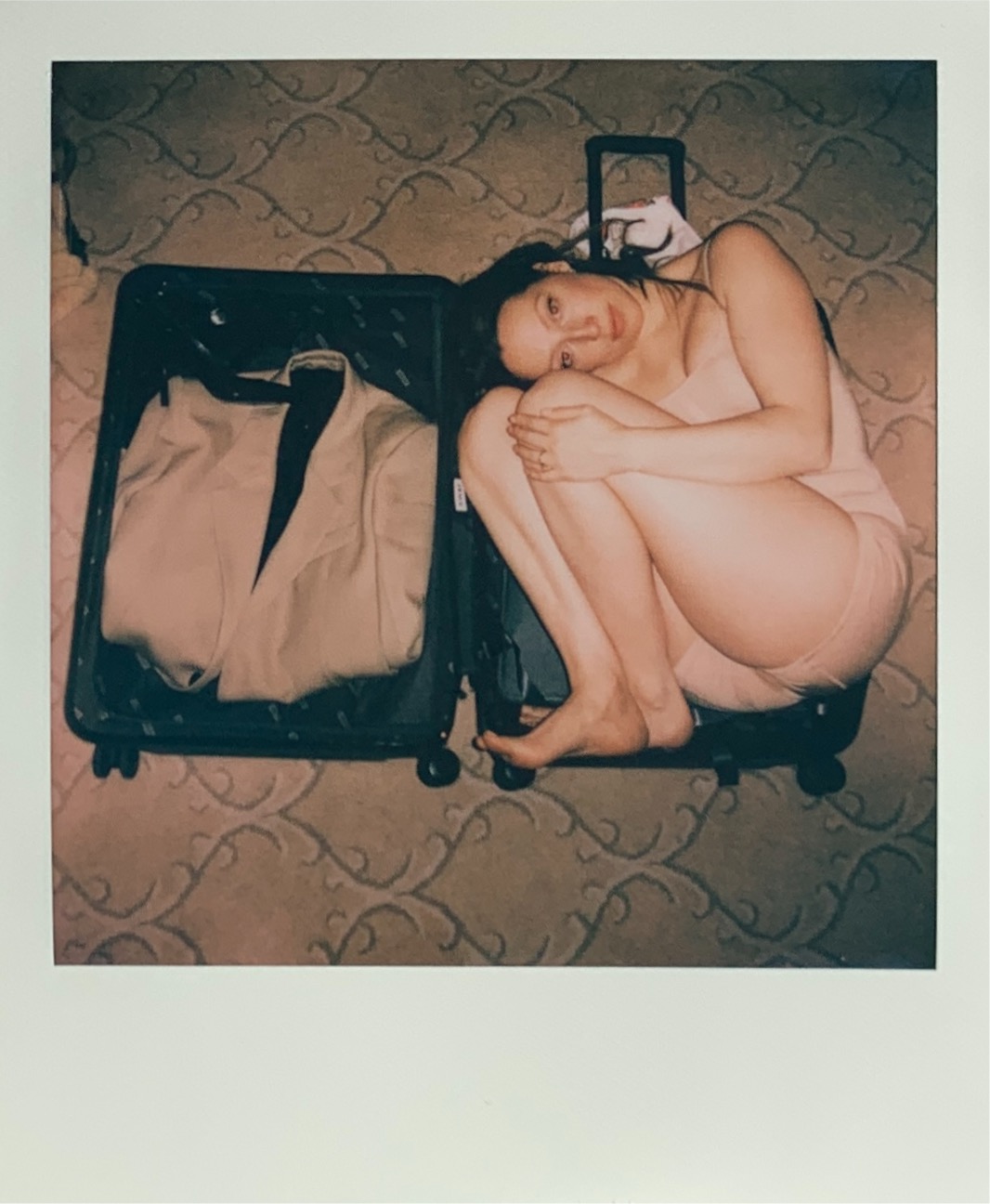

PEN15‘s Maya Erskine and Anna Konkle Are Winning the Popularity Game

- Anna Konkle.

- Maya Erskine.

Maya Erskine and Anna Konkle have earned a reputation for mining the collective trauma of middle school. Over two seasons of their cringe comedy PEN15, the pair conjure a vision of early aughts adolescence that feels, as Erskine has put it in the past, like an “interminable hell.” But somehow, it’s also cathartic and sweet and deeply, wonderfully, horribly, heartrendingly funny—enough so that it received an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Comedy Series earlier this year. Konkle and Erskine first met in an experimental-theater workshop while studying abroad in Amsterdam, and have remained close friends ever since. Their bond endured the rest of their undergraduate years at NYU, a bicoastal stint when Konkle attempted to leave the entertainment world for good, and even their first creative collaboration—a Kickstarter-funded Web series called MANA—during which Konkle took up residence on Erskine’s couch. (That’s how they met Sam Zvibleman, a writer and director on PEN15 and the inspiration behind the show’s “Sam” character.) They also, unexpectedly, became mothers mere months apart, during a worldwide pandemic no less, earlier this year.

Today, the pair have a steady stream of new projects on the horizon: among other things, Erskine will appear in the upcoming Obi-Wan Kenobi series on Disney Plus, and Konkle is completing a memoir. Sadly for the avid fans of PEN15, this likely means the show’s current season, now streaming on Hulu (called 2B), will likely be the last. During a recent stay at the Standard Hotel, the two shared a meal and chatted about middle school, the ups and downs of the popularity game, and—head-trip warning for everyone who thinks of the 34-year-olds as forever 13—what it’s like to become a mother. —EVELINE CHAO

———

MAYA ERSKINE: Okay, so going right for it—

ANNA KONKLE: Do it.

ERSKINE: How old were you when you first masturbated? And what did you think when you heard of girls doing it, when we were 13?

KONKLE: I never heard of girls doing it. Ne-ver.

ERSKINE: At that age? Wow.

KONKLE: I think it has to do with the community we moved to outside of Boston that was predominantly Catholic. Sex was not talked about. I mean, guys would joke about jerking off, but the idea that girls were masturbating never crossed my mind.

ERSKINE: So you didn’t even know it was a possibility that you could get pleasure from yourself?

KONKLE: I guess not. Actually, when I was in seventh grade, that’s when the “Icebox” rumor started, that I had masturbated with an ice cube. And really, in fifth or fourth grade, I played Truth or Dare and dared someone to put an ice cube in their underpants. And I was like, “I’ll do it,” which is really weird and who I was and am—

ERSKINE: I can so see that moment.

KONKLE: I know. I thought it was funny. But I never in my wildest dreams thought it was sexual or could be construed as something sexual because I was so not connected to that side of myself yet.

ERSKINE: Right.

KONKLE: So when it surfaced in this way in seventh grade, that was mortifying because not only was it not true, but I wasn’t there yet. And the way that people perceived me going into high school, to be sexually somewhere I was not—I got a lot of attention for that, good and bad. Good as in, I liked getting attention from the older guys.

ERSKINE: Yeah.

KONKLE: But it was also sexualizing me when I wasn’t ready. And I think that experience caused me to even vilify masturbating as a girl and woman more than I would’ve naturally, because I was so ostracized by my fellow girls about it. They hated me. There were signs put up about me that said “slut” with my picture and shit like that.

ERSKINE: It’s crazy.

KONKLE: But I also remember getting so many IMs even before the Icebox, from guys asking if I masturbated. Anyway, I didn’t masturbate until, I want to say like, 24. I had already had sex before—

ERSKINE: That experience made you want to run away from it.

KONKLE: I think so. I know there was something about my own sexuality that I put bottom of the list. All I cared about was the person I was being sexual with feeling pleasure. It wasn’t about myself until a long time later. And I didn’t realize that I was repressing that.

ERSKINE: It’s so funny because even though I did do that, originally, I also didn’t give myself pleasure in my experiences with men. It was all about servicing the man and I didn’t know how to connect the two.

KONKLE: How old were you and did you hear about it before you did it?

ERSKINE: I think I discovered it organically. It was an urge that I felt strongly.

KONKLE: I’m jealous of that.

ERSKINE: It didn’t feel great though. I felt a lot of shame for so long.

KONKLE: I know, that’s our patriarchal society.

ERSKINE: I felt like a monster.

KONKLE: I’m so sorry that you went through that. But just discovering the physical urge naturally, I’m sad that I didn’t get that feeling.

ERSKINE: But you felt hints of it. Like as you watched Saved by the Bell, you would get a tingle—

KONKLE: Yes, you know everything.

ERSKINE: What is Scituate like? Be brutally honest—like if I went to your school in seventh grade. I find it fascinating that we grew up in such different places.

KONKLE: My school was predominantly white. Very Catholic, very preppy and WASPy. There were outliers, of course. I was relatively included at first in elementary school, and then very much ostracized. And then I figured out how to play the game, I think. There is a part of Scituate that was homophobic, and could be racist; unfortunately I saw that in our school. It’s interesting because the “Shadow” episode that we did, with fetishizing Ume: I think I saw that happen in our school. So I think you would’ve experienced racism.

ERSKINE: Blatant, not microaggressions?

KONKLE: I might be naive, but I think it would’ve been microaggressions. Obviously this is horrible, but I think you would’ve been both revered and fetishized.

ERSKINE: Remember how I looked, just want to spark your memory—

KONKLE: [Laughs] I don’t know. If you’re alluding to nobody liking you, I think in my school, you would’ve been sexualized in a way that is in our show.

ERSKINE: There were moments at my school similar to that actually. In my yearbook, being called Lucy Liu, like, “Give me those $5 hand-jobs.” And that was attention from a seventh-grader that was cool, so I thought, “Great, he’s kind of sexualizing me, so maybe I’m kind of hot.” Which is … yeah. But he did it as a joke, to be like, “You’re nothing even close.”

KONKLE: What do you mean?

ERSKINE: I mean, I was called ugly bitch by his friend, so—

KONKLE: Ugh, I could kill him.

ERSKINE: I think he’s an actor now.

KONKLE: I do think we would’ve been best friends in middle school though.

ERSKINE: I think so too.

KONKLE: Maybe I’m naive, but I think I would’ve recognized racism and been ride or die for you and would’ve spoken out.

ERSKINE: I think you were able to straddle this line of fitting in while still having your unique sense of self there. I’m curious about your sense of humor growing up in that town. When did you know you were funny?

KONKLE: I never thought of myself as funny. But I think it was part of my survival mechanism from when I was very, very young. My dad was very funny. My mom’s funny in a different way, unintentionally. Which I also have. People will laugh and I’m like, “What’s the joke?”

ERSKINE: But then we’re all dying laughing around you because you’re being hilarious.

KONKLE: I have a weird part of myself that doesn’t totally pick up on what’s happening or what’s funny. Or I’ll be on a different page when everyone’s talking about something—

ERSKINE: That’s what makes you so lovable. But there’s also a side of you that is intentionally funny, and it’s irreverent funny.

KONKLE: Everyone would say that about you. But I don’t think a lot of people would meet me and say that I’m funny.

ERSKINE: No, you’re quirky. Quirky funny.

KONKLE: Quirky funny, there you go.

ERSKINE: Because you also let it come out. I’m thinking of when we [first met] in Amsterdam. You were very goofy funny, and outgoing and not afraid. And I was inspired by that because I was scared to make any joke or do anything that might fail. But you don’t have that fear.

KONKLE: You’re right. We’ve talked about this, I grew up as an only child, so I had to put myself out there. I went on a cruise, and had to introduce myself to people or else I’d be alone. I’m just used to things failing and people not getting me.

ERSKINE: That’s why you’re so funny, because you will throw any idea that comes to you out there. And out of 20, there’s one that no one in their goddamn right mind would ever come up with, and it’s the most genius idea.

KONKLE: That’s so cuckoo. I think I’m just really used to being misunderstood and … I think I have some learning differences, probably? You’re laughing because it’s true.

ERSKINE: I’m laughing because it was so genuine and emotional for a moment. And then you’re like, “I have some learning differences.” It’s just a very funny way to put it.

KONKLE: I do because I would break story and everyone would be like, “We have no idea what the board says.”

ERSKINE: It’s like A Beautiful Mind.

KONKLE: I’ve always had trouble learning the way other people did. There was suffering there, but also stuff that I learned to embrace and appreciate. I think we’re both very visual. I’ll just see six scenes in my head really quickly, and have to get it out—

ERSKINE: Which is why you write so fast.

KONKLE: You’re the same way. You have a certain visual thing I’ve not seen replicated. First of all, you are a genius writer—

ERSKINE: We’re not going to go into compliments. But I appreciate that.

KONKLE: I mean, you set a very high bar, don’t you think?

ERSKINE: You’re asking me, do I know if I set a high bar? I can’t think of myself that way.

KONKLE: Maybe it’s because you traveled so much when you were young, but every part of you is set at such a crazy high bar. And you raised the bar for PEN15, in a way that I’m so grateful for, because I’ve learned so much from you. You had more experience in filmmaking also, and your brother’s this amazing editor, and your dad is a very high-level musician, and your mom… you’re all very down-to-earth, kind, loving, funny, smart, but the bar is fucking high.

ERSKINE: Wow. It’s so nice of you to say. It sparks a memory of being in theater, actually, and never feeling like we killed it. And kind of applying that to everything I did, sometimes to a negative degree. It’s not that I can’t be fulfilled, but it’s never like, “It’s great and it’s the best.” I have to keep trying to make it better and go further.

KONKLE: Why do you think you have that instinct?

ERSKINE: Because I think if it ever felt like, “Great, I did it. That was amazing,” I would stop.

KONKLE: There’s a humility in everything.

ERSKINE: Yeah, from my mom’s background. Japanese culture is definitely about underplaying everything, being modest about your accomplishments. So that’s an aspect of it.

KONKLE: You are very self-deprecating, I have to say. You’re not one to just take a compliment.

ERSKINE: But I’ve learned how recently.

KONKLE: You’re much better now. It’s a very endearing quality, but I also think it’s great when you’re like, “Yes!”

ERSKINE: What’s interesting is that sometimes I have an insane amount of confidence and then the next day, it’s like crippling insecurity about the very same thing.

KONKLE: You are definitely an interesting dichotomy of those two things. Like, the questioning—

ERSKINE: The questioning = is part of my process. I remember talking to a therapist and being like, “I have to stop being insecure.” And she’s like, “Well maybe you doubting the things you’re doing every day is what creates the thing.” I don’t want that to always be the case.

KONKLE: As long as it’s not torturing yourself, right?

ERSKINE: Right. I would like to experience the, “Wow that was great.” But it’s more fun to experience, “Wow that felt great.” Trying to focus on that as opposed to, was I good or not.

KONKLE: I aspire to that too. But it’s not easy. I think that’s the way we line up also.

ERSKINE: The fact that Scituate is a fisherman’s village on the East Coast feels so exotic to me. I know there are downsides to having a small community where everyone knows everything about each other, but I grew up in L.A., so it was kind of vast. At one point I was going to move to the East Coast during middle school, and then it fell through.

KONKLE: I bet if you had, you’d like it. Or maybe it would’ve been the mixed bag that most people’s middle school experience is. I felt more comfortable in Vermont, so it was a culture shock, because I was used to a bunch of hippies and we were Unitarian and there was a lack of diversity there. Vermont does not have a lot of diversity, but—

ERSKINE: Well, even though I was in a big city, the school I went to had a lack of diversity…This shrimp…

KONKLE: You don’t like it?

ERSKINE: No, I can taste, like, that tap water—

KONKLE: Oh no, that’s not good. Don’t eat that.

ERSKINE: No. But this French onion soup is so good.

KONKLE: You’re right, it tastes like tap water. I weirdly like it, but I don’t know what’s wrong with me.

ERSKINE: Is it okay?

KONKLE: I think it’s fine. What age were you when you were the least popular? And were you aware when it happened?

ERSKINE: Seventh grade. That was where the shift happened.

KONKLE: Because you were cool before that.

ERSKINE: I wasn’t cool, but I was with the cool girls.

KONKLE: So you were a version of cool. You have to own that. If you hung out with the cool people, you were a version of cool.

ERSKINE: Well it was a small school and we all were there since kindergarten. So I got along with a lot of people. And in sixth grade I clung very tightly to these girls and I was getting pushed away slowly, and I could not face that reality. So seventh grade felt like my most miserable, lowest point. I don’t know if other people saw me as unhappy. I hid it.

KONKLE: Right. As we do.

ERSKINE: Kindergarten was probably my peak. I’m not kidding.

KONKLE: That’s hilarious. I love that.

ERSKINE: In elementary school, I was a wildcat. I was so confident. I had not a care in the world. But middle school is where it started to change. I would raise my hand and get made fun of for what I was asking, or little things like that.

KONKLE: Fuck middle school. Brutal.

ERSKINE: And then tenth grade, I switched schools, and it was way more diverse and bigger, so it wasn’t as stifling. So I had a rebirth. I know your most unpopular year was fourth or fifth grade. When was your peak?

KONKLE: Maybe senior year. Because you’re also the oldest. There was a culture in my school [where] the older girls bullied and threatened the younger girls. I remember how wrong it felt when I was a freshman. It was such a trope: The people that were bullied as freshmen were bullying the freshmen as seniors. That blew my mind.

ERSKINE: Why repeat the pattern?

KONKLE: I feel like people need to know about pumping. When you were directing the Yuki episode in our last season, you were breastfeeding when you came to set. Because I knew nothing about pumping, all those logistics.

ERSKINE: Not just that, the many rules about breast milk. How to store it, how long it lasts if the baby’s lips have touched the bottle… Also, I don’t listen to the rules about how long it can stay fresh in the fridge before you freeze it. I have sometimes left breast milk in the fridge for six days.

KONKLE: Really?

ERSKINE: Should I not?

KONKLE: I don’t fucking know.

ERSKINE: A doula would tell us about this, but I don’t know.

KONKLE: I had no idea you have to pump every three hours. And trying to work while you do that? I just started pumping in front of all the men in the room all the time.

ERSKINE: Yeah, same.

KONKLE: I was like, “Look away, or not.”

ERSKINE: If we were in another country, we would probably get paid maternity leave. Here it’s like, “I don’t want to hear about your period. I don’t want to hear about your baby pain.” I’m like, if men were bleeding from their buttholes once a month, for a week—

KONKLE: Oh, billboards everywhere.

ERSKINE: There’d be a national holiday every week for the, fucking, butthole bleeds.

KONKLE: And somehow the bleeding would be, like, marketed into the hottest thing that’s ever happened.

ERSKINE: There’d be blood everywhere.

KONKLE: The older I get, the more I say “the patriarchy.” You know it’s true because you’ve been with me for three days.

ERSKINE: [Laughing] Agreed. It’s so true.

KONKLE: It’s just, the unmasking of it as I get older, its in places I never saw it before. I was so naive with my liberal self and my hippie parents, da-da-da. The male gaze.

ERSKINE: Oh, same. What are you most excited to do when you get a full break? You haven’t had a break in years.

KONKLE: There’ll never be a full break because I have a baby. Next.

ERSKINE: Does your life look like what you wanted it to when you were in college and when we fantasized about our futures?

KONKLE: My god. Beyond my expectations. What about you?

ERSKINE: Yeah. There are big dreams still. But when I think about what I thought I wanted and what I’m actually experiencing, this is so much cooler. Not to be like, we’re living cool lives. It’s just that your idea of what success or happiness is looks very different. Um, what would you do if your daughter said she wanted to be a writer and actor?

KONKLE: I would say, “I will support you, and I’m proud of you, and I want you to experience a lot of different things.”

ERSKINE: That’s what I’d do. Of course, inside I’d be like, “That will be hard but I can’t protect you from everything. Maybe I’m not going to set you up with an agent right away, but I would let you join theater. Learn to love it.”

KONKLE: One hundred percent. Love that.

———

Special Thanks: Polaroid