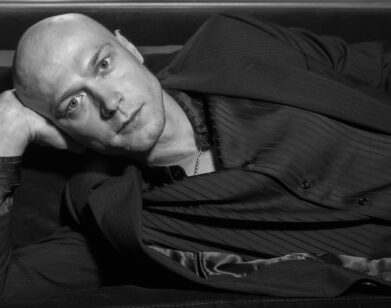

In Conversation

Max and Charlie Carver Get Inside Each Other’s Head

It’s easy to assume that Max and Charlie Carver have been inseparable since birth. As identical twins who both became actors, the 32-year-old brothers have been appearing in projects together since 2008, when they made their debut as the rebellious Scavo twins on Desperate Housewives. Since then, they’ve acted together in MTV’s Teen Wolf, HBO’s The Leftovers, and the 2017 modern Shakespeare adaptation A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But the truth is, Max and Charlie, who hail from San Francisco and were born seven minutes apart, separated while at boarding school as a way to carve out a sense of individuality. They reunited at the University of Southern California, and by then, the Carvers’ acting career was well underway. Since then, they’ve avoided the obvious trap of being typecast as lookalikes. Max went on to appear in projects like The Office and the 2014 romantic comedy Ask Me Anything, while Charlie made his Broadway debut in The Boys in the Band (he reprised his role in this year’s film adaptation), and most recently starred as the wounded war veteran Huck in Ryan Murphy’s Netflix thriller Ratched. It’s been several years since the Carver brothers appeared on screen together, a reality that will change on March 4, 2022, when Warner Bros. finally releases the pandemic-delayed The Batman. The brothers have been in England shooting their secretive roles in the hotly-anticipated project, but took some time off for their first ever interview—with each other.

———

MAX: This is my Barbara Walters moment.

CHARLIE: You prepared questions?

MAX: Oh yes. I have.

CHARLIE: Oh lord. Here we go.

MAX: Let me start with this: We’ve been through thick and thin together. Knowing what I know about you, in terms of disappointments and moments of questioning “if you’re on the right path,” why do you keep doing what you’re doing?

CHARLIE: That’s the first question? [Laughs] I guess part of it is a sense of curiosity about what’s possible. How can I challenge myself? In what ways can I feel like I’ve found my own version of success, and what does that feeling of success afford me as a person, moving forward?

MAX: What do you mean? Define success.

CHARLIE: I love that you have to be kind of naïve to want to work in a creative field. I don’t mean having to be overly simplistic about the world, but you have to maintain a kind of innocence, or a hopeful state of mind. And I can’t imagine getting practical. I don’t think I could do anything else.

MAX: What do you mean?

CHARLIE: Well, I can’t imagine dropping that disposition to go work in a different field. I’m trying to remember what made me want to go into this as a kid, and I think it was being moved in one way or another, and feeling the potential of being able to do that for other people, and understanding in an intrinsic way that that had value. Now, the battle has been trying to convince myself that it still has value, particularly in a world where there are so many other actionable ways to affect people’s lives.

MAX: But the value is you get to empathize with a belief system whether you’re consciously doing it or not. You’re getting to explore parts of yourself that may be dormant. And I think when people see that on the screen, it wakes up that dormant part of themselves. It’s like soul exercise.

CHARLIE: I hear that.

MAX: In terms of Ratched, what did you want to convey that you felt other people might not understand or see in your character?

CHARLIE: Another arrow of a question. I’m not sure I wanted to go in and convey anything. I think you learn from the story in front of you and you discover something in that process.

MAX: What did you learn?

CHARLIE: I always have to battle my own insecurities, or feelings of being limited somehow in actually embodying the character and the circumstances that are in front of me.

MAX: You’re speaking in abstracts.

CHARLIE: Thank you, Max. With Huck, what was being asked of me was to sit with and live with the experience of a war vet—in a very specific, genre show—and I just wanted to trust that the product would come out of that. I’m so grateful to Ryan Murphy, not only for the opportunity, but for how much creative freedom was given to me. We spoke a little bit about the images and things that came to mind for him, and I was on the same page.

MAX: Such as?

CHARLIE: The Elephant Man, and then some of my own stuff. Want to know a funny one? Do you remember that skunk from Bambi? Flower?

MAX: Yeah.

CHARLIE: I kept feeling Flower a lot.

MAX: [Laughs] Just to be clear, these are all leading questions. For me, whenever I get a role, whether it’s just working on stuff on camera, or writing, or whatever, I’m going to start recognizing some belief system that I have that I was in complete denial about. What did this story kick up for you?

CHARLIE: A lot of my own stuff around masculinity. To really believe myself as a war vet in a nursing uniform, the physicality or the posture, was challenging. I think a lot of that comes from the very narrow definition of masculinity presented to me as a kid, and how as a gay man, I didn’t feel inside of that definition. I felt naturally excluded by it. So anytime a character where these traditional tropes of masculinity come in, it always brings up stuff for me. It’s surprising that it does, and I’m grateful that it does, because it always deepens something that I wanted to learn about myself. And I usually find I end up going against those tropes. Having to find my own way in response to them. There’s a core question that I always return to in any work, even if it’s just writing, or the work of being in a relationship: Am I enough?

MAX: Enough of what? You have imposter syndrome when you’re portraying “masculine” characters?

CHARLIE: Yeah, kind of. More that by doing my own thing, I’ve somehow failed at the task. But the sense of fraudulence, or insecurity, or imposter syndrome is somewhat akin to doubt, and I think it’s important to see that for what it is and welcome it. Doubt isn’t a bad thing. I’ve definitely made some peace with that feeling of not knowing what I’m doing and feeling kind of fraudulent while I’m doing it. I would like to believe everybody feels that way.

MAX: Yeah, when I feel doubt, it’s a somatic experience. It’s this empty feeling in my body. Feelings with no label or no name. But I think that’s okay. Not to name it, just to allow it. Gonna change gears here: What do you think is your most attractive quality?

CHARLIE: Really having your Barbara Walters moment. [Laughs] Oh my god. I don’t know anymore. I feel pretty bland these days, I’m not going to lie.

MAX: Are you trying to suggest that modesty is your most attractive quality?

CHARLIE: [Laughs]. Shut up. I’d like to think I’m a good person. I’m open-minded. I think that’s attractive. I say yes to things.

MAX: What’s something you think about a lot that you believe other people should spend some more time thinking about? I know, that’s going to make you sound arrogant, no matter how you answer that question.

CHARLIE: Yeah, it is! What do I think people should sit with?

MAX: Maybe it was a bad question.

CHARLIE: No, it’s an interesting question. Hmmm. You were the one who taught me to use this technique: It’s so important to remember that we were all children. That the person in front of you, whether you’re meeting them with a sense of judgment, or excitement, or whatever, that they were once a child. I think that’s something valuable to sit with.

MAX: Um, I never said that. I think I said that kids will identify with anything. By which I mean, kids get defined by other people around them and that’s not right. I forget who said it, but “the law of the jungle was kill or be killed, now it’s define or be defined”. But maybe don’t bother defining anything or anyone. Let it be a question. You and I have gotten in some arguments about defining oneself through abstract language, through labels, instead of just saying, “Hey, I’m Charlie.”

CHARLIE: Yeah. I think that identities and labels are useful in that they can be ways into finding community and showing solidarity across a real shared experience. But I don’t particularly love using “gay” as an adjective to describe myself. I don’t have an issue with being seen that way, but it’s just such a strange…

MAX: I don’t think you can or should try to boil down your personality or who you are into descriptors. I don’t think it’s possible. I think it’s unwinnable.

CHARLIE: Exactly. And that word in particular, “gay,” has become something monolithic. It stands for something that I’m not sure I want to be in communion with. To clarify, what I mean is that it’s absolutely something I identify as. But I think it’s a word that has come to stand for an exclusionary, very privileged, and largely white experience… Well, I would be in denial if I didn’t fall into that, categorically. But it’s not my identity. It’s not the “all” of who I am. And so I bristle at that word a bit. And don’t want to feel defined by language. Then again, I am happy to identify as one letter in this broader coalition, the LGBTQ coalition, if that makes any sense. It becomes a position from which to speak from and engage with the world. I have no idea how we got here.

MAX: We were talking about you. Now we’re going to change the subject. If you could write the musical of your life, using the music of a known artist, who would that be ?

CHARLIE: I don’t know why there hasn’t been a Dixie Chicks musical. I would feel very represented by that.

MAX: Hm. Why?

CHARLIE: You know the answer. You’re setting me up. [Laughs] “Cowboy, Take me Away” is such a great song! It would really rip on stage.

MAX: Okay. Next question. Did you play The Sims as a kid?

CHARLIE: You ask this question on dates, don’t you? I know you do.

MAX: Don’t deflect. What did you do with your Sims characters? How did you spend your time on The Sims?

CHARLIE: Fine. I know you have this theory that that question is like this Rorschach test.

MAX: Sort of, yeah. For dysfunction.

CHARLIE: The “Red Flag” test. I would build these beautiful houses and then I would separate the family members into rooms and remove all the doors, and watch what happened. So that the people would just be locked in these doorless, windowless rooms. Trapped. That was my big fear as a kid.

MAX: You had a lot of fears as a kid.

CHARLIE: That’s true. But I was really afraid of waking up in a house where it’s like, “Where is everybody”?

MAX: You get to start over today. What age would you pick?

CHARLIE: I would go back to kindergarten.

MAX: You would go back to kindergarten?

CHARLIE: I remember. We’re lucky. We were identified as “twins,” but we really got to separate, I think internally, from each other at that age.

MAX: To add some backstory here, we were always very different. We even went to different boarding schools across the country from one another. We didn’t really grow up together. I mean, we did. We fought so often our parents had to build a wall between us while we were sharing the same room. We went to different boarding schools, pretty much decided we were going to go to different universities.

CHARLIE: And somehow both ended up in L.A. Just a little bit of backstory. But I think at that age, six or so, you’re just responding to the world. You’re not actively trying to do anything differently. You’re learning to survive, or adjust to your environment. You are adjusted by your environment. So I wonder what it would have been like to grow up somewhere else.

MAX: Where?

CHARLIE: I don’t know where. I don’t have a lot of resentment about that time, but I do feel shaped by having grown up in a rural pocket of the world. I will always wonder what other parts of myself could have better and more naturally flourished from that age. And I think a lot of damage comes from feeling forbidden from certain possibilities. I wanted to do all sorts of things in kindergarten. I wanted to dance, I wanted to be a good student, I wanted to make art, I wanted to act, and all of those things were not acceptable because they made you a “queer.”

MAX: And you got teased a lot.

CHARLIE: And so we both found out, in this strange experiment of being genetically identical people with a controlled set of similar circumstances, how different inputs played out.

MAX: But because we’re twins, I still had to witness what you went through. It’s not like I walked away unscathed or untouched by your pain. If anything, I felt I had to compensate for it.

CHARLIE: It’s symbiotic. I don’t think I got away from your pain. I felt all that, too. We’ve already talked some about masculinity and identity and I think you can feel that stuff as a kid, but you don’t know how to do anything about it. Expectations. You don’t have any language to be able to articulate what it is, but you just feel it. So if I could go back – I’m just curious, in this “experiment” that is our lives as identical twins – what happens if you plug in or take out certain inputs? A setting? A time period? How does that shape the person that you are? Had I grown up somewhere else, how might we have diverged in other ways? This also goes back to the acting stuff. When I step into a role as an actor, are the circumstances going to be enough information for me to become that character? Or is there something else that’s beyond what is circumstantial that shapes a person? A kind of spiritual force, or self, independent of those inputs?

MAX: I believe that we get whatever stories we need until we don’t need a story anymore. And in this profession, the stories we need find us. Do you see an underlying pattern in all of the stories you’ve been given? Not just stuff you’ve shot professionally on film, but other stuff, too. Plays, books, stuff you write. I remember you doing Angels in America in college. Life and Limb.

CHARLIE: I often end up playing people who have been maimed, or hurt, or who feel ugly.

MAX: What do you think the common denominator is?

CHARLIE: I don’t know if I can generalize as far as a common denominator. I’ve always been attracted to telling stories where there is an externalization of trauma or a loss, something put into your life that you didn’t choose. Huck was such an important character to me in that way

MAX: Well, if I can reflect on my own stuff, I keep getting stories and I’m realizing that for whatever reason I keep getting a lot of villain stuff thrust upon me, at least on paper. And what I’m learning is, it’s very hard for me to own my goodness, my softness in a vulnerable way. But it’s there, too. In the “bad”. So I’m also learning I can’t compartmentalize in that kind of way with myself. And I want to own more softness in my day to day life.

CHARLIE: And if I’m being perfectly honest, I have a difficult time finding myself beautiful, in a way. There’s something about all these characters and how beautiful these characters are that reflects something back to me like, oh, that is something that I am too. Beauty is a big word.

MAX: Just say it. “I am beautiful.”

CHARLIE. [Laughs]. Anyone can find a time in their life, and this theme goes all the way back to being a kid, of feeling different, of feeling ostracized in some way, and trying to find an explanation for it. I think how I interpreted those feelings was that I was that I’m the ugly duckling. And even though we’re identical twins, in my head that was how I related to the situation. I saw myself as the ugly duckling compared to you. And the work I’ve gotten and I’m interested in, well, it’s just a theme that’s preoccupied my life.

MAX: Are you sick of that story?

CHARLIE: We are so predisposed, even in our conversations not on the record, to talk so seriously about things, Max. My turn to ask you something. How do you hope to have fun in the next five or ten years?

MAX: My idea of fun is getting out of L.A., in a car, not having a plan. Driving up the 33, north of Ojai, and finding a hot spring and running around naked. And not bringing cameras, not recording it, not trying to do anything. It’s to be in nature with no plan no feeling that needs to be accomplished. It’s just butt naked in a natural spring. That’s fun.

CHARLIE: Well, I’m always down to do that, too.