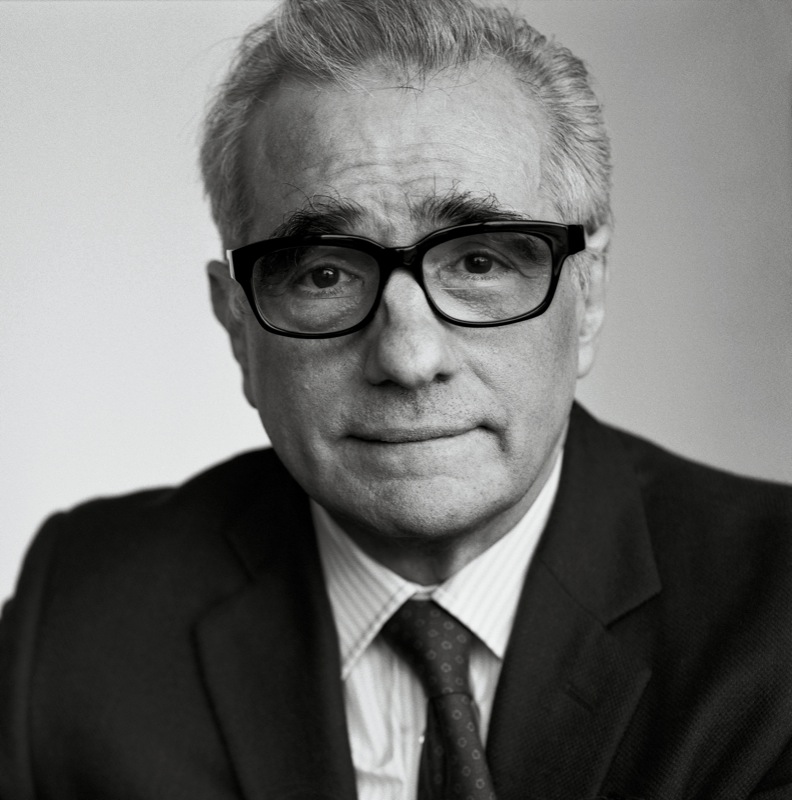

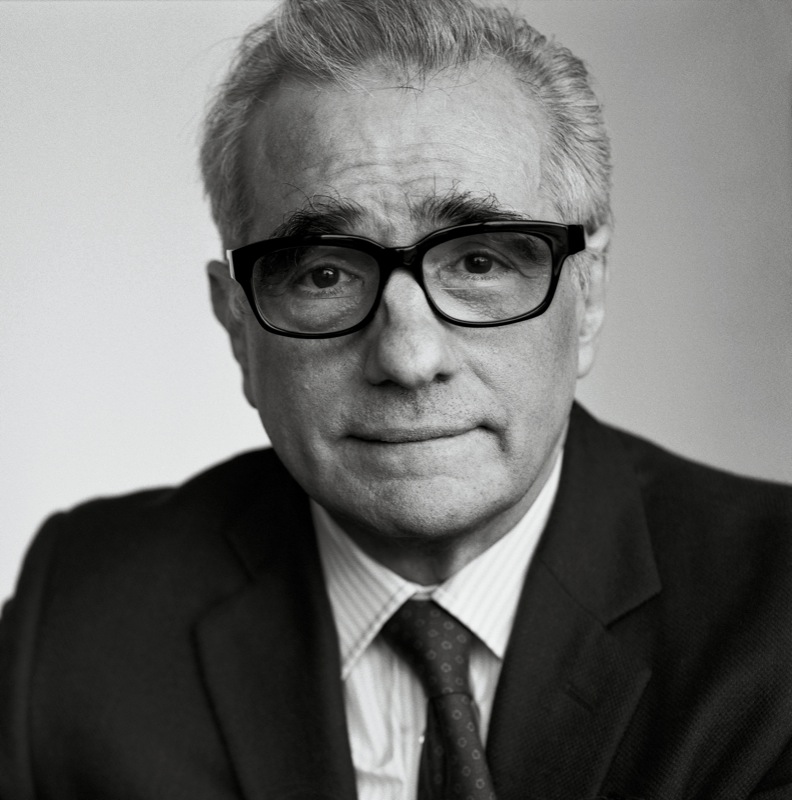

Martin Scorsese and SpikeLee Are the Kings of New York

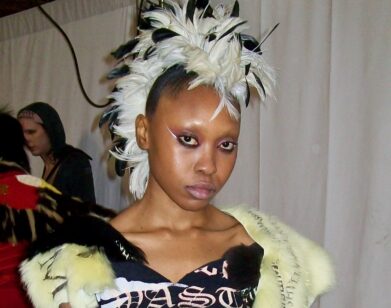

Although a certain nebbishy auteur has come to stand as the paradigm of the New York director, there are arguably two other candidates well suited for that honor. Martin Scorsese and Spike Lee were not only both raised in the city, but they’ve built a close friendship while comparing notes over the years. Lee’s most recent film is the searing drama Miracle at St. Anna, which follows a troop of African-American soldiers in the heart of Italy during World War II. Scorsese, who grew up in New York’s Little Italy, of Sicilian roots, is completing work on the dramatic thriller Shutter Island, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Ben Kingsley. In addition to directing, the 66-year-old Scorsese has founded two organizations, the Film Foundation, in 1990, which advocates and supports the preservation of America’s film heritage, and the World Cinema Foundation, in 2007, devoted to the preservation of film in developing countries. It’s clear that both causes are things that Scorsese cares about, as he seems to remember important moments in his life by the films he was watching at the time. Here Lee asks his friend when he’s finally going to make the ultimate New York epic.

———

SPIKE LEE: I’m here with my man, Martin Scor-sese! He’s working on his next film. How’s it going?

MARTIN SCORSESE: Well, it’s going okay. We’re in the middle of our first cut.

SL: And the title of the film is?

MS: Shutter Island.

SL: Starring?

MS: Leonardo DiCaprio, Mark Ruffalo, Ben Kingsley, Michelle Williams, Emily Mortimer, and Patricia Clarkson, among others.

SL: You and Leo got a good thing going, baby.

MS: Yeah. [laughs] It’s been going for a few years now.

SL: Tell us about this new project you have.

MS: Oh, the World Cinema Foundation. One night I was watching late-night films on . . . I think it was on Showtime. There was this film called Yeelen. The picture had just started at 2:30 in the morning, and the image was very captivating, and I watched the whole thing. I discovered that it was directed by Souleymane Cissé and came from Mali. I got so excited. I had seen Ousmane Sembène’s films from Senegal—he was the first to put African cinema on the map, in the ’60s—but I hadn’t seen anything quite like this . . . the poetry of the film. I’ve seen many, many movies over the years, and there are only a few that suddenly inspire you so much that you want to continue to make films. This was one of them.

SL: So you’re telling me that Martin Scorsese, the father of cinema, needs inspiration to make more films?

MS: Well, it gets you excited again. Sometimes when you’re heavy into the shooting or editing of a picture, you get to the point where you don’t know if you could ever do it again. Then suddenly you get excited by seeing somebody else’s work. So it’s been almost 20 years now with the Film Foundation. We’ve participated in restoring maybe 475 American films. A couple of friends of mine were talking, and they said, “You know, since you liked Cissé’s film so much, wouldn’t it be great to try to work out something international that would deal with films from underdeveloped countries, not necessarily European or Asian?” With Italian films or French films, the archives are there. But when you go to Mali or Burkina Faso, it’s very difficult. You haven’t been there?

SL: Not yet.

MS: We went in December to see what it was like.

SL: How many times have you been to Africa?

MS: I’ve been to North Africa many times. This was the first time I’d been in the southern part of the Sahara. But, of course, the music is the key for me there.

SL: I think you love music more than cinema.

MS: [laughs] I think so. Music is the purest form, don’t you think?

SL: Would you agree with me that musicians are the greatest artists?

MS: Yeah, they’re the purest and the greatest. I mean, music totally comes from your soul. I just remember growing up with guitar music and jazz. I would play these 78s that my father had in the ’40s, and all these images came to mind. That’s the way I’ve always worked—listening to music and getting pictures from the music.

SL: Your father was a funny man.

MS: Yeah, I know. [laughs] I look in the mirror, and, now that I wear these glasses and I’ve shaved the beard, I look just like him.

SL: I’m beginning to look like my father too! [laughs] That’s kind of a scary thing though. How has New York changed from when you grew up here?

MS: I lived on Elizabeth Street between Prince and Houston. But the neighborhood has really changed. You’re talking about paying $40 a month for rent in 1952, and for a place like that now you’d pay . . . who knows how much?

SL: There is no affordable housing here in New York City anymore.

MS: I know. But what’s also crazy is the Bowery . . . When I was living there, the Bowery still had the elevated train. It was really wild, noirish-very, very dark and sinister. Then the elevated train came down. There’s no way that you could have imagined, coming from that world, that the neighborhood would ever be so chic. In a way, I like the fact that finally in New York older buildings are being restored rather than being torn down. I love that the neighborhood has become the way it is. It still has the history. It’s in the streets. You can still feel it.

SL: When will you grace us and shoot another film in New York City? What was the last film you shot here?

MS: I made Gangs of New York in Rome, The Aviator in Montreal and Los Angeles, The Departed and Shutter Island in Boston . . .

SL: The last one was Bringing Out the Dead. That was 10 years ago.

MS: I’ll come totally clean with you. Half of Departed was shot here. Half of it. Interiors and some exteriors too. In Red Hook.

SL: How friendly were you with Frank Sinatra, when he was alive?

MS: [laughs] I met Frank Sinatra maybe two times.

SL: Had he ever seen any of your films?

MS: Yes. I spoke to him on the phone about Raging Bull and put a couple of his songs in there. He was very gracious about it. He gave us permission for two of them. I wanted three, but he said, “No, that’s it. Two.” I said, “Okay.” Then I met him backstage at the Academy Awards, and he was a gentleman. I think it was the night Ellen Burstyn won for Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. He was the emcee, I think. I may be wrong about that. But he was at least the presenter of that one section. People wouldn’t go nearer than, like, 10 feet around him. It was like a wall. He just moved, and the atmosphere moved with him.

SL: I’ve got a funny Frank Sinatra story. In Do the Right Thing, the wall of fame was of all Italians. One of the pictures burned was Frank Sinatra’s. So a couple of films later, I’m doing Jungle Fever, and there are three songs I want to use of Frank Sinatra’s. Frank Sinatra doesn’t want to speak to me. I have to speak to his daughter Tina. I said, “Tina. Miss Sinatra. Frank, your father, I adore him. He was my mother’s favorite performer. I chose these songs from September of My Years because that was her favorite album, and I meant no disrespect by burning his picture at all!” [laughs] So they made me squirm a little bit, but they relented and let me use the three songs in Jungle Fever.

MS: It’s so funny because nobody had ever done that before. You’re in the middle of Do the Right Thing, and your character says, “And fuck Frank Sinatra.” We were offended.

SL: If you look at Do the Right Thing, Jungle Fever, and Summer of Sam, there’s a relationship between African-Americans and Italian-Americans. You’re an Italian-American. I’m an African-American. We both grew up here in New York. What is it about both of our groups that has such a dynamic here in New York City? Is it because we’re so similar?

MS: There is a similarity, culturally. There is a similarity especially in the way the two groups live near each other and interweave cultures.

SL: Especially in the South Bronx, where Al Pacino grew up.

MS: It was different from where I lived. Where I lived, it was all Sicilian.

SL: Is Fellini’s Roma one of your favorite films?

MS: I prefer it even to Amarcord.

SL: Would you do the New York version of Roma?

MS: [laughs] It’s not a bad idea. I think I’ve been trying to do it, from Mean Streets and Taxi Driver to Raging Bull and Gangs of New York . . . The thing about it is, I’m obsessed with this city. I just find it so remarkable. You really treasure this city when you go to different countries and you see that there is no mix. When you get back to the city, it’s such an exciting place. New Yorkers, we walk in the street, we talk to ourselves. But the issue is the energy, the excitement, and the different ethnic groups all mixed together. We’re spoiled being here.