IN CONVERSATION

Mark Anthony Green Tells Cord Jefferson Why Making Movies Is His Favorite Drug

“If they don’t let you do it, die trying to do it. And if they let you do it, die doing it as many times as you can.” That’s the mantra of Mark Anthony Green, the journalist-turned-filmmaker whose debut feature, A24’s Opus, just celebrated its opening weekend. Green’s cult-infiltration thriller stars Ayo Edebiri as a young reporter who travels to the compound of a reclusive pop star (John Malkovich) for an ill-fated press event. To mark the occasion, Green got on the phone with fellow filmmaker and Oscar-winner Cord Jefferson, who showed up to their date with his Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay in tow. “I bring it everywhere,” he quipped. “Why wouldn’t I?” In a wide-ranging conversation, the two talked about the pleasures and perils of obsession, ditching journalism to pursue filmmaking, and the adventure Green took to Latvia to ensure that Malkovich knew he meant business.

———

MARK ANTHONY GREEN: I’m excited about this.

CORD JEFFERSON: Me too, man. I did one of these with [Ryan] Coogler last year. I’m excited to chat with you. I want to talk to you firstly about your short film.

GREEN: Yeah, Trapeze U.S.A.

JEFFERSON: That’s your actual directorial debut, right?

GREEN: That is my actual directorial debut. I made it like eight years ago, give or take, and I went into debt making it. I shot it on 35 millimeter film.

JEFFERSON: You financed the whole thing yourself?

GREEN: I financed most of it, yeah, with credit cards and other shit. I made it with friends of mine that don’t make movies, so it was very wild west. I wrote the script in Microsoft Word. I wanted to make a movie, but there were no humans in my life where I could be like, “Yo, how do I do this?”

JEFFERSON: You didn’t go to film school?

GREEN: God, no. The only thing that Trapeze did is prove to me that I am a filmmaker and should dedicate the rest of my time and talent to being as good of a filmmaker as possible.

JEFFERSON: That was something else that I was going to ask you. I hadn’t heard about Trapeze, but I knew your work as a journalist at GQ.

GREEN: I fell out of love with it.

JEFFERSON: Was that you biding your time until you made another movie?

GREEN: I mean, not always, but it was. When I met Will Welch and Jim Nelson, I was 19 and in college. I wrote for them occasionally, but I was writing for Fader and Spin and a bunch of other places—

JEFFERSON: When you were 19?

GREEN: When I was in school, yeah. I was a terrible student.

JEFFERSON: Me too, man.

GREEN: It took me five years to graduate and I had no money, so it was the worst. But nobody looks at themselves the way other people look at them.

JEFFERSON: I think that’s especially hard for artists, because one of the things that makes you a good artist or a good journalist is that you have to be observant. You have to be keenly aware of people and what’s going on around you. And I think it makes artists paranoid that people are paying attention to us because we pay attention to other people. Does that make sense?

GREEN: I think so. I have very low paranoia for a Black man.

JEFFERSON: I was going to say. [Laughs]

GREEN: I don’t think the world’s out to get me. There’s people in institutions that will never love and accept me, but also, I don’t want anything from most of them. If I leave them alone, they leave me alone.

JEFFERSON: This is interesting because your first foray into film was predominantly you. You financed it and made it with people who had never made films. I talk a lot about the rigid institutions in Hollywood and how they’re so fucked up in how they keep telling the same stories and won’t let other people in. So how did it feel entering that world, to finally make a film that you couldn’t finance? All of a sudden, you’re within institutions and there’s limits to what you can do because it’s like, “It’s our money.”

GREEN: Well, I grew up playing basketball, and when you grow up playing a sport, you never complain that they’re playing defense. They’re supposed to. You try to find your way through it in the style that you want to do it. When that quiets down, the artist takes the wheel and hopefully makes something thoughtful. The second I got to New Mexico and I got with my crew and the actors, it was a hundred percent art.

JEFFERSON: What else did you learn from Trapeze U.S.A? You said that you learned that you want to be a filmmaker.

GREEN: Three important lessons. The most important one was, if they don’t let you do it, die trying to do it. If they let you do it, die doing it as many times as you can. The second thing that I learned from it is, the guy who was doing our sound came up to me and was complaining about lunch. I hadn’t eaten in days and hadn’t thought about it. At first I was annoyed ’cause I’m doing all these things and he comes up to me complaining, and then it dawned on me, “Oh, the experience of making this movie matters so much more to them because they’re not going to stand with the product. I’m in a privileged position.” The people that go into this battle with you, be mindful of how each day feels to them. You’re willing to be uncomfortable or miserable because this is your vision, but it does not happen without them, and you need to care about how they feel every second.

JEFFERSON: Absolutely.

GREEN: The third thing it taught me—I’m curious as to what you think of this—is how it’s borderline impossible to be a filmmaker and have a normal life.

JEFFERSON: Yeah, dude. This is funny because I’ve been going through a tumultuous time in my personal life, and one of the problems is that I am obsessed with my work and I don’t see any signs of that slowing. It’s really hard to be obsessed with your work and also maintain a healthy, balanced relationship. Maybe it seems crass to talk about it in these terms, but to be able to do what you want to do to earn money is–I was talking to a friend recently who was like, “If you can do that, you have won at life.”

GREEN: Strongly agree.

JEFFERSON: The vast majority of people do not get to do what they want to do to earn money. That’s how I go into it thinking: “I’m obsessed with this because I feel like I won the lottery.”

GREEN: There’s a self-seriousness and navel-gazing pretension that comes with two men sitting at a table talking about obsession. Obsession is usually fine when it’s a one-man thing. Obsession when you have a family and are responsible for other people’s happiness makes it more complicated. You don’t have kids, right?

JEFFERSON: I donated sperm to a lesbian couple, so I technically have two children with them. But I’m like Uncle Cord. I don’t raise children, but that’s a tangent.

GREEN: We absolutely cannot push past that.

JEFFERSON: We’re talking about you. But I will say, that diminished my primal urge to have kids. I think I still want children of my own, but I can chill a little bit on that. I credit some of my success in my career to the fact that I have always had no attachments. It’s been like, “Can you move to New York next week?” And, look, that has resulted in multiple failed relationships because I’m just like, “I got to go do this.” But again, I am okay with that sacrifice because this is something that I’ve really wanted for a long time. I’m okay with that being my life. Maybe one day that’ll change.

GREEN: I know that even in the heartbreak and the misery that comes with filmmaking—because there’s so much heartbreak and misery in filmmaking, as you know—this is the happiest I can be.

JEFFERSON: That’s what I was going to say. We both come from journalism. I feel like I had a pretty cushy gig, and you had a fucking great one at a cool place.

GREEN: I would be making way more money and life would be way more comfortable. But so many people go their whole life and don’t find their thing. When you find it, to turn your back on it, I don’t know that there’s anything sadder than that.

JEFFERSON: What do you feel like you do in filmmaking that allows you to spread your creative wings even more than you were?

GREEN: It is just the scale of it. Music’s a big thing in Opus for story reasons because John [Malkovich] plays a musician, but also the score itself. There is a control. The first song is “Maggot Brain” by Funkadelic. The last song is “DLZ” by TV On The Radio. Lenny Kravitz makes a cameo, so there’s Black kid coolness through all of these generations. Frankly, I know two people that even care about that, but I spent god knows how much time trying to pull off this through line. That made me so deeply satisfied. As a director, I don’t think you get to spend a lot of time satisfied, but in those moments where it comes together—I’ve never drank, never smoked—iu’s the closest to what I assume finding your drug of choice is like. It’s quick, orgasmic, nothing feels better, and you chase it until you get it again.

JEFFERSON: I think that’s what Spielberg said when he was accepting some award. It’s the closest he’s ever come to flying. Anyways, you took a risk to be uncomfortable and leave this great job and just say, “I’m giving this all up to go follow this dream.” What was the first step when you were out? Was it scary to quit, or did it feel like you were breaking shackles?

GREEN: There were some things publicly and privately that I struggled with. I was really, really depressed. Everybody was depressed in 2020, so to say you were depressed is like, “No shit, bro.” But as I look back at it, I was really depressed. It felt like the real shackles were that I wouldn’t get to do it. That was the thing I was the most afraid of and am still afraid of. That’s the outcome that keeps me up at night—not getting to be on set, not getting to craft stories like this.

JEFFERSON: I think one of the interesting things about your film is that you have a relative newcomer in Ayo [Edebiri], and then you have a legend in Malkovich. Which felt more scary to you—working with this young hotshot that everybody loves, or with this dude who is legendary and has been doing this for decades? Was that intimidating?

GREEN: Intimidating? If I’m being honest, I don’t know that I ever felt intimidation.

JEFFERSON: You’re a Black man without imposter syndrome, which is rare. I’m not saying that as a bashing. I just think that imposter syndrome is so common at this point.

GREEN: I don’t want to make it seem like I don’t have insecurities. I definitely have insecurities, but I felt very prepared. It takes so long to make a movie that I felt more honored than anything else. Maybe my imposter syndrome just manifests itself in other ways. There were times where–I wasn’t intimidated by John—but I needed to make sure that he was going to go there with me. I don’t know if you’ve seen this, but there’s an interview where Matt Damon talks about John on the set of Rounders.

JEFFERSON: He says, “I’m a terrible actor.”

GREEN: Right. There’s lore on a $40 million, 60-day movie. On a movie that’s shot in 19 days, like Opus, he can’t show up and be Russian. So as soon as he agreed to do the film, that interview went viral. I’m like, “Fuck.” I called some other directors that have worked with him and I was like, “Man, I got to look John in the face and say to him that I’m dead fucking serious about this movie. I know I’ve never made a feature before, but I will demand that you really bring it.” I called his agent, who I love, and I’m like, “Yo, I got to talk to John. Where is he at?” He calls me back and he’s laughing. He’s like, “John is in Riga, Latvia, but if you want, you can email him.” I’m like, “Nope. I’m going to Latvia.”

JEFFERSON: Are you serious? Oh my god.

GREEN: I fly to Latvia. The war at the time had been going on for two months. It’s dangerous. When you book the ticket, there’s a warning that pops up.

JEFFERSON: I would not have done that.

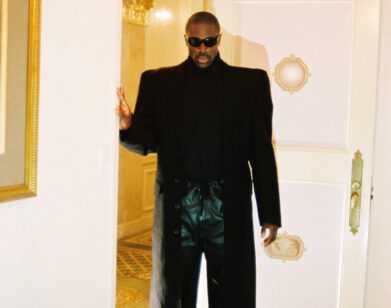

GREEN: I swear I’m not making this up—my flight from London to Riga, I was the only person on the commercial flight. I got on the plane, and they closed the door. It was the only time I thought, “This might’ve been a mistake.” But I don’t give a fuck, that’s what obsession will do to you. To the homies in Latvia, it’s a wonderful place. I don’t want this to seem like I’m shitting on it, but I got off the plane and didn’t know what to expect. There seemed to be buildings from the last scuffle that hadn’t been cleaned up yet. So I went to Riga, which is a really cute, quaint town. The most expensive hotel was $132 a night. I get to this restaurant. Everybody’s staring at me, by the way.

JEFFERSON: Probably not a lot of Black people.

GREEN: There are no Black people, and there are zero Black Americans. Literally when I was checking into the hotel, the person went and got another person—not to help them, but to be like, “He’s American.” So I go meet John for dinner, and he’s wearing an eyepatch. I’ll show you a photo just for proof. I have all these things I’m going to say to him, but I’m like, “Let’s start with the eyepatch. What’s going on?” He’s had emergency surgery on one eye, and he has 20% vision in the other eye. I’m not good at math, but that means he has like 10% of the total vision that god gave him. He’s in Latvia directing a play in Latvian and doesn’t speak Latvian, and he says, “So, why are you here?” I looked at him and I was like, “I need you to know how serious I am about this movie.”

JEFFERSON: Was he the first person to sign on?

GREEN: Ayo had signed on, but I knew Ayo.

JEFFERSON: What was his response to that?

GREEN: It was a moment of silence, and then he started dying laughing. He ordered a bottle of wine, and we talked for hours about the character and basketball. We talked about movies and plays and him being from the Midwest. We talked about why I wanted to make this film, and then I pushed my flight because I wanted to see him direct people that don’t speak English. I didn’t know what they were saying in the play, but I saw him make the play better. It was a really good lesson on emotional directing. So we spent a few days together, and John was the most fearless, directable gentleman and thoughtful partner I could have asked for. The lack of ego that he brought to set every day—nobody’s living comfortably when the budget’s that small. It dumped snow one day.

JEFFERSON: It looked cold.

GREEN: It was freezing. He never once complained. He shoveled his own snow to get to set.

JEFFERSON: That’s amazing, really. I was going to say, did you write the part for Ayo? Because you said you guys are friends.

GREEN: I started writing it before I had ever met Ayo. But for a lot of us, Ayo is something out of our dreams—a Black woman with that complexion, that amount of talent, that originality on and off the field. I feel so grateful to live in a time where she’s a leading woman.

JEFFERSON: Absolutely. Something we’ve seen in the Oscars is a lot of directors advocating for more control. Do you feel like you were as free as you wanted to be making this film, or is there another level of freedom you want for your next project?

GREEN: I’m not afraid to say the studio stopped me from doing this or that, but there’s different types of freedom. There’s freedom in the person that puts the money up letting you make the decisions you want to make. There’s freedom in you having enough talent to actually execute the thing that’s in your head. And there’s freedom in resources. If I had fucking 25 days to shoot this movie, how much different would it be? I don’t think that I had the freedom to do exactly what I wanted to do, but I also haven’t earned that freedom. Sean Baker’s been making movies for 20 years, and he just won four Academy Awards. He deserves freedom in every sense. He should get the money, he should get the talent, he should get the frictionless creative path. I don’t mind proving myself and working—again, that’s the thing about being dedicated to it. So many people felt like Opus came out of nowhere because I didn’t tell anybody about Trapeze.

JEFFERSON: Despite the fact that it won film festivals.

GREEN: Sure. It was deeply me, but technically bad because I had no clue what I was doing.

JEFFERSON: It’s the first pancake. It tastes good, but you’re not going to put it on the plate.

GREEN: You won’t put it on top, that’s for sure. You eat that one yourself. I think there are battles that I had to fight with Opus—that I should have had to fight—that I probably won’t have to fight on the next one. But then there are battles I’ll have to fight again. I think there are battles that you’ll have to fight, despite the fact that you have an Academy Award. Also, I want to say on the record, Cord brought his Academy Award here.

JEFFERSON: I bring it everywhere. Why wouldn’t I? Are you kidding me? I’m impressed by hearing you say that your first film inspired this desire, but also you saying, “It didn’t work.” Again, the heart of an artist is, “You know what? I missed the mark this time, but I’m going to move on and make something else.” I think that’s what prevents a lot of people from having the dream, a fear of public failure.

GREEN: I’m sure this means I’ll probably die broke and alone, but for me, the best part of this job is production. The part that I’m still wrapping my heart and my head around is actually the exhibition. Every artist, you look at your piece and all you see are the flaws.

JEFFERSON: Dude, I can’t watch anything that I make.

GREEN: It’s a cliche, but it’s the truest thing. I fucking love pre-production.

JEFFERSON: Really?

GREEN: Us all just in there, getting after it. Before we got to pre-production, I had moved to LA and was still fighting to get this movie made. But I sat down with Robert [Pyzocha, Green’s producer] just to check in with him, and he showed up with all these sketches of the rats. It blew my mind. On the page, I describe them, but if the thing I wrote on the page is exactly what’s on the screen, I’d be disappointed. Those moments genuinely do feel like magic. That’s the high that I think we chase and chase and chase, and then you die.

JEFFERSON: Paul Schrader says, “A script is not a work of art. A script is an invitation to other people to come make a work of art with you.” I think that’s a really nice way to look at it.

GREEN: Except for The Social Network. That script by itself was a work of art. But, Paul Schrader, I would never disagree with you.

JEFFERSON: Do you really feel like you found your life’s purpose?

GREEN: I feel like I have found the avenue that I want to dedicate my life to getting as good at as possible. I’m 36.

JEFFERSON: Young man.

GREEN: I’m aging terribly. I didn’t have any gray hair before Opus.

JEFFERSON: Yeah, man. It’ll do it to you, those long nights.