Stomaching America’s Hunger Problem

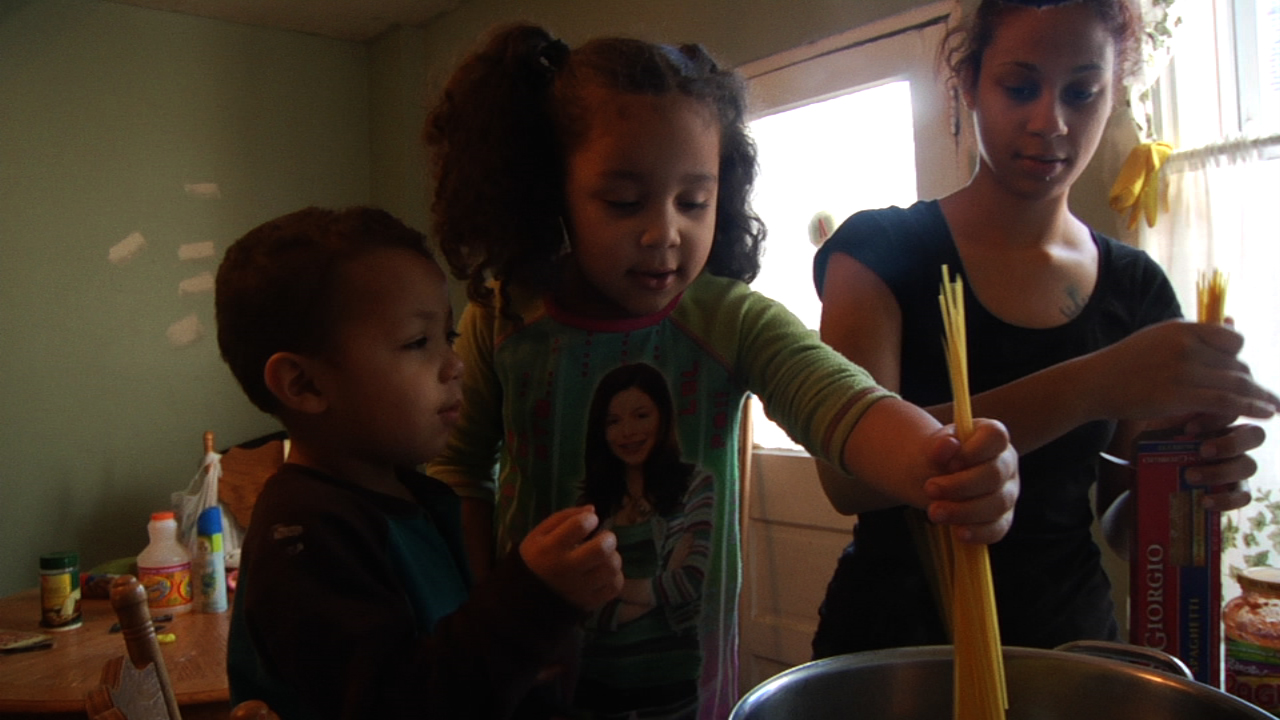

ABOVE: BARBIE IZQUIERDO (FAR RIGHT) AND HER CHILDREN IN A PLACE AT THE TABLE. IMAGE COURTESY OF MAGNOLIA PICTURES

For 49 million poverty-stricken Americans, trips to the grocery store are few and far between. The proof is in the (off-brand) pudding, potato chips, and soda consistently replacing fruits and vegetables as major food groups on the healthy-eating totem pole. Unlike their organic counterparts, heavily processed foods are cheap and easily accessible in both urban and rural areas across the nation. In penny-pinching straits, nutritional content has gone by the wayside—empty calories rule the junk-riddled playground.

Exploring the discrepancy between America’s abundance of natural food resources and the rising number of malnourished Americans in A Place at the Table, documentary filmmakers Kristi Jacobson and Lori Silverbush present three unique hunger cases to color their narrative. There’s Rosie, an average fifth-grader from Collbran, Colorado, who relies heavily on her grassroots community for daily sustenance—nutritious or otherwise. There’s Barbie, a down-and-out single mother of two whose income is too high to qualify for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and too low to provide nutritional meals for her growing children. Then there’s Tremonica, an obese second-grader from Mississippi whose severe health problems are exacerbated further by a poor, junk-fueled diet. Jacobson, Silverbush, and the film’s celebrity commentators Jeff Bridges, Tom Colicchio, and Raj Patel agree: in a resource-rich country like the United States, one in four children hungry is one too many.

JAMIE LINCOLN: Often, documentary filmmakers share some sort of deep-rooted connection with their subject matter. Do you have a personal connection with food insecurity? If not, why was it important for you to make A Place at the Table?

LORI SILVERBUSH: The last time I directed was a fiction film based on the real lives of kids who were locked up in juvenile detention. Kind of amazingly for me, I learned that just about every kid I met there had experienced hunger at some point or another. In fact, I had said to one kid, “God, it must be really hard for you to be locked up,” and she said, “Well, I get three meals here a day.” I was stunned by that. I thought, Oh my God, what is that about? We have kids who are looking forward to being in lockdown so that they get fed? A couple of years later, I was mentoring a young girl and she was having some difficulty in school, so we helped her get into a school that was for kids with learning challenges. It was a private school, and I was feeling really good about it… only to get a phone call from the principal that she was foraging in the trash for food because this was not a school that had federally subsidized free meals, like public schools do. Unwittingly, I had made her hungrier. She was losing what had turned out to be her only meal of the day. That made it very personal for me all of a sudden. I was also watching the philanthropic world always getting together to do these fundraisers for hunger, and they were doing such an amazing job. Each year, it seemed like they were raising more and more money, but at the same time, the numbers of hungry people were going up and up. It seemed to me like the response that we had, as a nation, didn’t seem to be fixing the problem. Sure, it was doing a lot to alleviate suffering in the immediate, but it wasn’t fixing it. I knew that there had to be something to this story, so that’s when I approached Kristi, who is a documentary filmmaker with a great reputation, and I said, “What do you think? Do you think there’s something worth looking into here?” and she thought there was. We started looking into it, and we were pretty amazed by what we found.

KRISTI JACOBSON: I was intrigued by the story that [Lori] shared with me about this young girl who was experiencing hunger and the devastating consequences right here in New York. For me, as a documentary filmmaker, I’m interested in telling stories of real people whose experiences tell us something about ourselves or our history, or who we are and our potential. For me personally, after we got through our initial research and meeting with different people, I began to understand how pervasive and insidious it is right here in America—but even more important was that it was hidden. I think the more I understood about the shame, the more important it became for me to tell the story.

LINCOLN: Interesting that you mention shame, as I noticed throughout the film there’s an overarching theme of suffering in silence. No one wants to scream, “I’m hungry!” from the rooftops, because the majority of your subjects mentioned there’s an element of embarrassment associated with not being able to provide for one’s family. Was it difficult to find subjects willing to openly discuss their struggles with hunger and food insecurity?

JACOBSON: It was difficult in multiple ways. On the one hand, it was difficult to narrow down the field, because there are so many—50 million, not a single county in America where there aren’t hungry people, or people struggling with food insecurity—so where do you start? Once we made some decisions about where we would be filming and the kinds of stories that we were seeing out there—you know, I’m a documentary filmmaker, so often I’m in the position of talking to people who are sharing stories that are critically important to share, but often difficult to share at the same time. I think for us with this film, one of the most important things was first getting to know the people in the communities in which we filmed. We spent quite a bit of time doing that, developing relationships that were based on trust and mutual respect and an understanding of the impact that sharing their stories could have. As you saw in the film, we certainly found ourselves filming with some pretty incredible and courageous people who were able to see that and overcome that initial—although ever-present—feeling of shame in order to hopefully share their story in a way that would affect lots of people and prevent hunger in this country from continuing to be such a problem.

SILVERBUSH: There was definitely reluctance. We were in areas like Collbran, Colorado, which is the far Western edge of Colorado, and the people there were very independent. They don’t believe in complaining, or blaming people for their own issues. We also found that one of the big hallmarks of this issue is that people tend to feel like they’ve failed somehow, or are somehow responsible for their own hunger or food insecurity, so getting past that wall of reserve was tricky. We took great pains to get to know people. We were introduced into communities by trusted people who vouched for us, and it was really an act of courage by a lot of people who understood that if they talked about it, maybe other people would and together we could destigmatize the issue.

LINCOLN: Rosie’s story of severe hunger affecting her concentration and ultimately her grades and attendance in school was heart wrenching to watch. As a child, how do you think Rosie’s perspective differed from Barbie’s, or one of your older subject’s?

JACOBSON: That’s such a good question. I think that Rosie’s ability to articulate the feeling of hunger and food insecurity so vividly and candidly is a function of both who she is as a person—which is someone with an incredible spirit—but also a function of her age and her youth. She managed to put words into something that very few adults that I came across were able to describe. There was a freedom in her that maybe over time—for example, as we saw with her teacher—that feeling of being inferior and issues with her self-esteem may make it a little difficult to articulate it. But Rosie was just so incredibly candid and unfiltered.

SILVERBUSH: The thing about kids is that they don’t have the broader perspective of what’s happening on a national level. Anything that’s going wrong in their world, they somehow assume is unique to them and they’re somehow to blame. It turns into an issue of shame. We saw this with Leslie Nichols, her teacher, who, only after we interviewed her a couple of times, did she reveal to us that she had known hunger as a kid. This was something that she had never even spoken to her own husband or her kids about; she carried it like her own deep, shameful secret, which is heartbreaking because it’s not her fault, it’s nothing she did. I think with someone like Rosie—without the intervention of people who know better, like her teacher, who was able to reach out, see the signs, recognize them and help her—it’s likely that kids, 17 million and counting in this country, are walking around thinking that they’ve somehow done something wrong and it becomes shameful. It’d be really great if we could change the dialogue around it so that these kids don’t feel inferior to everybody else.

LINCOLN: In contrast, Barbie’s story marks an entirely different set of hunger struggles as a single mother trying to support two children. Interestingly enough, when Barbie finally lands a full-time job, she no longer qualifies for government assistance and struggles to put food on the table more so than when she was unemployed. I have to ask—are we living in a broken system?

SILVERBUSH: I think it’s pretty clear that we are. The Food Safety Net programs is this country … and that includes SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), Food Stamps, and WIC (Women, Infants, and Children Food and Nutrition Service), work really, really, well; but they work well when they are adequately funded, and they need to be modernized. If we could modernize them to reflect current realities—for example, if you get a job and it’s a low-paying job, it doesn’t necessarily mean you’re going to immediately be able to take care of all of your expenses, particularly things that have backed up over time from being unemployed. Millions and millions of people in this country are one health care crisis or one illness away from Barbie’s situation, and we need to reflect the realities of where people are in their lives when we look at these programs. They need to be modernized and they need to be funded adequately, and protected from the constant dialogue around budget cuts.

JACOBSON: I absolutely think we’re living in a broken system, and that’s one of the examples where truth is better than fiction in terms of telling the story. Often with documentaries, you’re crafting the story in the edits, because you’ve captured so much footage, and there’s so many different ways you could possibly tell a story. When that happened to Barbie, we were quite shocked, and we were close to finishing the film in some ways, but we did our research further, and we learned that what happened to her was very representative of what happens across the country. That specific problem of getting knocked off for just being a few dollars over is called the Cliff Effect. It was really upsetting to witness, but our hope is that exposing that particular flaw in the system will lead to reform. That particular aspect, that particular problem, requires reform and modernization of the Food Stamp Program.

LINCOLN: I really enjoyed the discussions about stereotypical images associated with hunger and starvation. Often times, we picture an emaciated African child when discussing hunger, and not necessarily an obese second-grader like Tremonica, who consumes empty calories such as pop and chips on a daily basis. Is this image of obesity diluting the United States’ hunger problem?

SILVERBUSH: I think the misconceptions around the larger issue are leading people away from what’s really going on. As we show in the film, a lot of people in this country are obese because of a form of malnutrition. One thing we’d like to do is to help people understand the correlation between a steady diet of empty calories—though you may not experience hunger pangs, you can’t really function well if all you’re eating are things like ramen noodles, or chips, cookies, and sodas, things that are quite typically inexpensive and affordable because of the way we subsidize the ingredients that go into them. The prices of really unhealthy food are kept artificially low, and that contributes to obesity. I’m sure there are people who just assume we can’t have hungry people in this country because so many people are obese, but once you start to understand that a major cause of obesity is inadequate nutrition, it really changes that conversation.

JACOBSON: I think that the invisibility of hunger in America—to the eye—is what’s keeping it invisible politically and to America at large. As we saw in the film, you don’t necessarily recognize a hungry child. There are a lot of prejudices and stereotypes that dominate, and I think that we need to take a closer look at why, for example, kids in that town are struggling with obesity. We need to look at whether a child is getting adequate nutrition and look at the whole picture, because it’s costing the nation a hell of a lot of money, as you saw in the film. It’s really born out of a lack of awareness and a lack of understanding of what the genuine cause of these problems are.

LINCOLN: While the film ends on a hopeful note, I couldn’t help but feel a little frustrated, given that such a large portion of responsibility lies in Congress subsidizing the production of healthy foods. Is there anything Americans can do to lend support on a micro-level?

SILVERBUSH: We had an elected official tell us that if as few as six people in his district call him about an issue, he’ll change how he votes, because for every person who calls, he’s assuming there are a couple thousand people who didn’t call who feel the same way. When you know that, it suddenly becomes a lot harder to stay disengaged from the political process. I think that our elected officials will get this right if they get the mandate from the public that we want them to. Until we express ourselves, tell them what we expect from them, we can’t expect them to do it on their own. Sadly, the ethical arguments alone are not enough to do it, but I think that if Americans decide that they want to let their elected officials know it’s time to fix things, it’ll be an amazingly powerful movement.

A PLACE AT THE TABLE IS OUT TODAY. FOR EVERY MOVIE TICKET, DOWNLOAD, COMPANION BOOK, AND E-BOOK SOLD DURING THE FILM’S OPENING WEEKEND, PLUM ORGANICS WILL DONATE ONE ORGANIC “SUPER SMOOTHIE” POUCH TO A BABY OR TODDLER IN NEED. FOR MORE INFORMATION ON HOW TO LEND A HAND IN STOPPING HUNGER, VISIT TAKEPART.