NEWCOMER

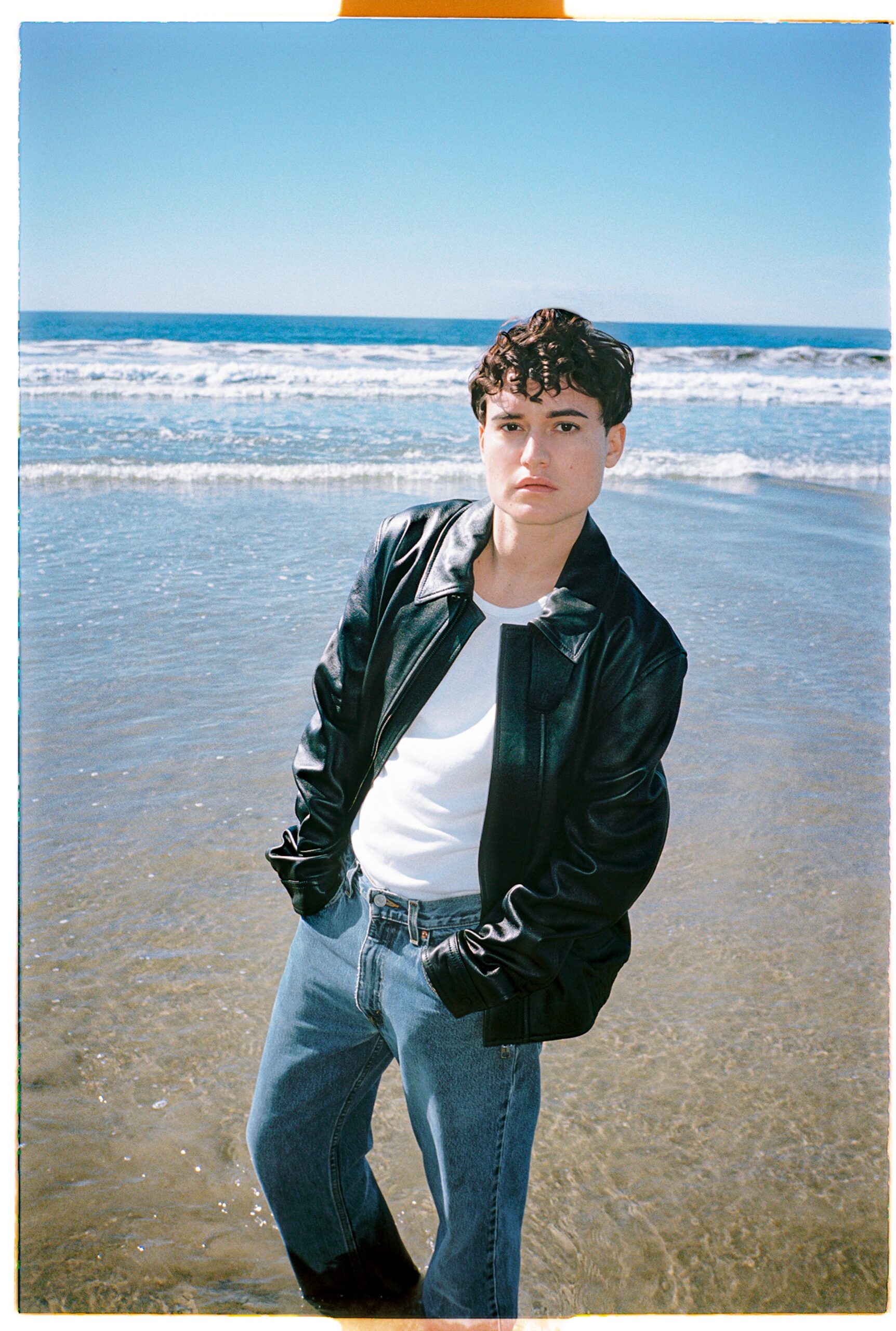

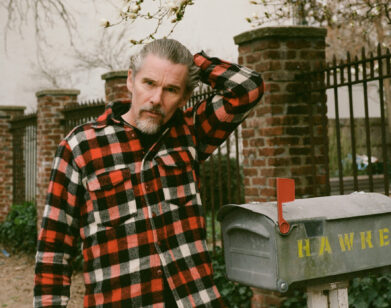

Lío Mehiel Tells Maya Hawke About Transitioning in the Public Eye

“I’ve had this recognition that there’s still a part of me that wants control,” Lío Mehiel told friend and fellow actor Maya Hawke last week. “Because, as a trans person, I wanted to have more of a say in how people understand me and view me more than the average cis person.” Over Zoom, the actor, writer, and artist opened up about transitioning in the public eye; their character in Vuk Lungulov-Klotz’s Mutt, now on Netflix, takes on similar challenges. The film, which premiered at Sundance last year, follows Feña (Mehiel) after he spends the night with his straight ex-boyfriend. Navigating the next day with a wretched hangover, Feña reunites with his younger sister and tries to figure out how to pick up his estranged father from the airport while confronting countless obstacles, like attempting to cash a check with a deadname. Calling in from New York, where the first snow of the season had just arrived, Mehiel told Hawke about adjusting to fame, being a multi-hyphenate, and their dream project: a stage adaptation of Giovanni’s Room.

———

MAYA HAWKE: All right. Here we are.

LÍO MEHIEL: Thank you for doing this.

HAWKE: No need to say thank you, I love doing these things. It’s such a fun way to talk to artists and engage as a community. My first question for you is a very simple one. How do you feel on set, and is it always different?

MEHIEL: I think it’s different for every project, because an indie film with your peers is so different from a 300-person set on an Apple show. But something that kind of stays consistent is this feeling of, I can’t believe it. And sometimes, because I’m pretty type-A and I can run a little anxious, it’s striking to me how easy it is to be the actor on the set. I produce, I direct, I write. When you’re doing that type of shit, you’re thinking of a million different things. But as an actor, I’m like, “Wow, this is such a gift that they’re building this safe cocoon for me to be still and vulnerable and curious and peaceful in what otherwise I know is the most chaotic vibe you can be in.”

HAWKE: You’re such a multifaceted artist. I mean, I’ve now seen your incredible sculpture work, you’re a director, you’re a writer, you’re a producer, you’re a performer. If you had to give up everything and pick one—

MEHIEL: I’m sort of romantic about this. I like to identify as an artist and a poet. I don’t call myself an actor very often. I don’t even really call myself a writer or director. Because I feel like what I’m here to do is experiment with how humans can be with each other and inspire other people to do the same thing. And so my trans-ness is my greatest work of art, and the way that I am with my mother is my greatest work of art, and the way that I am as a lover, the way that I hope I occupy space on set is like, “Can I allow this to be a creative exchange with whoever it is I’m with?” That’s when I feel grounded, you know what I mean? I think acting provides an outlet for the amount of emotional energy that I have in my body. I need to be working out to get out all of my energy, otherwise I’m like a dog chasing its tail and I can’t focus.

HAWKE: That’s beautifully put. I really understand what you’re talking about, especially what you said about your relationships being works of art and putting a lot of creative energy into them.

MEHIEL: Yeah. What is a central pillar for you?

HAWKE: Something that brings me comfort in life is craftsmanship, because I like the idea of knowing how to do something well enough that you can do it even when you feel like shit.

MEHIEL: Wow, yeah. I do think that being a technician of something gives me a sense of, “Okay, I have a skill that I can contribute to the group, if nothing else.”

HAWKE: I completely agree and it feels really good. And if I wasn’t doing any of the things that I’m doing, I would just want to be an art teacher of some kind, or an acting teacher. Have you seen Poor Things yet?

MEHIEL: Yeah.

HAWKE: I love that movie.

MEHIEL: Yeah, me too.

HAWKE: Hearing about the rehearsal process that they did, just playing with each other, I think that’s my favorite part about acting. It’s what most of what acting school is like, and not what life as an actor is like, mostly.

MEHIEL: Yeah. It’s my dream to be able to work on a film or something on screen where there is a kind of theatrical approach to rehearsal and exploration.

HAWKE: That would be so nice. I’ve done some things where we had rehearsal time, but no one wanted to play any games. A lot of actors hate theater games.

MEHIEL: I know. They’re cringe.

HAWKE: Yeah, they are cringe. I guess it’s my kind of cringe.

MEHIEL: Me too.

HAWKE: How do you manage the public side of your life now that you’re in a Netflix movie, and an amazing one? How did that make you feel, when stuff was coming out about that? Were you googling your name constantly? Were you able to avoid that?

MEHIEL: Yes. I was googling myself a lot. It’s bizarre. It’s not something that I know how to do organically. I think some people have a skill, in addition to being an artist, which is being a public figure. I think that I have a skill set of being a public figure in so far as I like to speak and I like being asked questions. But when it comes to just having my image taken, almost like a simulacrum of myself, a persona instead of a human… For example, I’m very long-winded. I’m so verbose, I can just ramble on for fucking hours. I got distracted this last year with the public piece of it. I was spending more time responding to interview questions than I was writing my script. Do you know what I mean? And I’m like, “Wait a minute, Lio, what’s the real art here?” It’s confusing and weird.

HAWKE: It is confusing. Someone said to me once, something that I’ve taken to heart, which was, “Yes, the press is not the real art, but there’s a good chance that more people will see and read your interview than your work.”

MEHIEL: Right, absolutely.

HAWKE: So much of your expression and creativity does seem very linked to identity. Identity is a big issue for me when it comes to press and being public because that’s the scariest thing. You don’t get to decide what you wear or what the picture looks like or edit the spread.

MEHIEL: Totally. I mean, there’s two aspects of this. I just recently did my first photo shoot where they dressed me, they decided my hair, they chose the photographer, they chose the final images. I had zero say and my heart rate picked up. Like, I’m Puerto Rican. Do you know how to deal with that kind of hair? I had this recognition that there’s still a part of me that wants control because, as a trans person, I wanted to have more of a say in how people understand me and view me more than the average cis person.

HAWKE: That makes total sense to me.

MEHIEL: I’m already a person who’s sitting on the horse, wanting to be a part of the process of communicating who I am. So releasing control is a learning curve for me and trusting in the fact that this image doesn’t have to represent me. If I don’t like it, it can just be out there and that’s fine. Another weird aspect of this is that I’m on testosterone, so my face is changing and my body is changing. I literally look different in photographs now than I did six months ago. When you’re an actor and you’re really good at knowing how to position yourself, your face and your body are your instruments. When that is changing in a way you don’t totally know how it’s going to unfold, and it’s the first moment that you’re ever being imaged publicly, I’m like, “Why did I choose this?”

HAWKE: And you’re in the middle of the journey, too.

MEHIEL: But I’m just following my impulse and desire because certain aspects of my trans-ness are not rational, and I don’t need to put them in a rational logic. I just have to trust if it’s something I want to be doing, I need to let myself have it.

HAWKE: Have you been meeting new people through your art? I’m sure that a lot of people have felt extremely seen by Mutt.

MEHIEL: Yeah. One of the most beautiful parts of Mutt has been the literal thousands of messages that I’ve received, and I know Vuk [Lungulov-Klotz], the writer/director has also, from really young trans kids and people who are trans but not out to their families. So many different kinds of queer people from different parts of the country and the world in different languages are DMing me like, “This movie is the first time I’ve ever seen myself in a movie.”

HAWKE: Let’s go!

MEHIEL: And for the first time as an actor, people in the industry or filmmakers who I really respect, they’re treating me a little bit differently. When you’re trying to build your career and no one’s watching, you’re just doing it over and over again hoping that something opens up for you. That feeling of it finally starting to open, it’s kind of beyond belief. I’ve had to rewire my psychology in order to meet the moment because I’ve just spent so much time being like, “I don’t need anyone to care about what I’m doing. I just gotta keep showing up and doing the work.” Then, all of a sudden, people start noticing.

HAWKE: I often think about this story about Sam Shepard. When his play premiered on Broadway for the first time, his friends came and kidnapped him from the after-party and were like, “You can’t go enjoy the party, you’re a playwright. Don’t let people kiss your ass.” It feels like there used to be this badge of honor around like, “I don’t put my songs on commercials. Fuck no, I don’t do press.” And I think it’s really all about how artists used to be paid. There used to really something of a middle-class artist, where you could say no to putting your song in a commercial and still buy a house someday. That doesn’t really exist anymore, which I think is the simple answer to why that’s shifted.

MEHIEL: Yeah. I think you’re right. I need to be able to look up and recognize that this can be sustainable. This is real. I do have a career. I do have work that I’m building, and then I can put my nose back down and be like, “All right, where are my homies? Who’s making work that I’m really excited about regardless of what resources they have access to or not?”

HAWKE: Yeah. I love working with my friends. It’s in moments where I feel a sense of larger belonging and of community and something bigger outside of myself when I’m happy. And when I feel like a valued cog in a good machine that I love, that’s when I’m like, “Let’s go, I love this lawnmower and I’m so happy to be this screw, and thank you all for coming to the lawnmower.” Do you relate to that at all?

MEHIEL: Yeah, a hundred percent. That’s such a beautiful way to put it.

MEHIEL: Yeah, that’s what I say too.

HAWKE: Do you ever want to do regular theater? Because that’s my big dream post-Stranger Things, to just do tons of theater.

MEHIEL: Fuck yeah. I was on Broadway as a kid.

HAWKE: I know. And salsa?

MEHIEL: Yeah, I was a professional salsa dancer.

HAWKE: Do you still dance?

MEHIEL: I am much too aware and humble to call myself a dancer, but I love to move and it’s a way for me to exercise my energy. If it’s some kind of movement-based theatrical piece, I’m down and it’s great. But yeah, I am just going to use this moment as an opportunity to manifest this: I want to be in an adaptation of Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin.

HAWKE: Yeah!

MEHIEL: I want to play Giovanni and I want it to be at New York Theater Workshop and then Broadway. It’s like, we need this play. We need it to explore masculinity. It’s no longer just about this guy being gay and how he feels about that. It’s about white masculinity, and I’m moaning at that, so I’m just saying that here to manifest it to the universe.

HAWKE: I love that book and you would be amazing. I feel it in my fingers.

MEHIEL: Fuck yeah. Wow, it’s snowing outside.

HAWKE: Oh. Are you in New York?

MEHIEL: Yeah, I haven’t experienced the snow yet. Now I know the planet is alive.