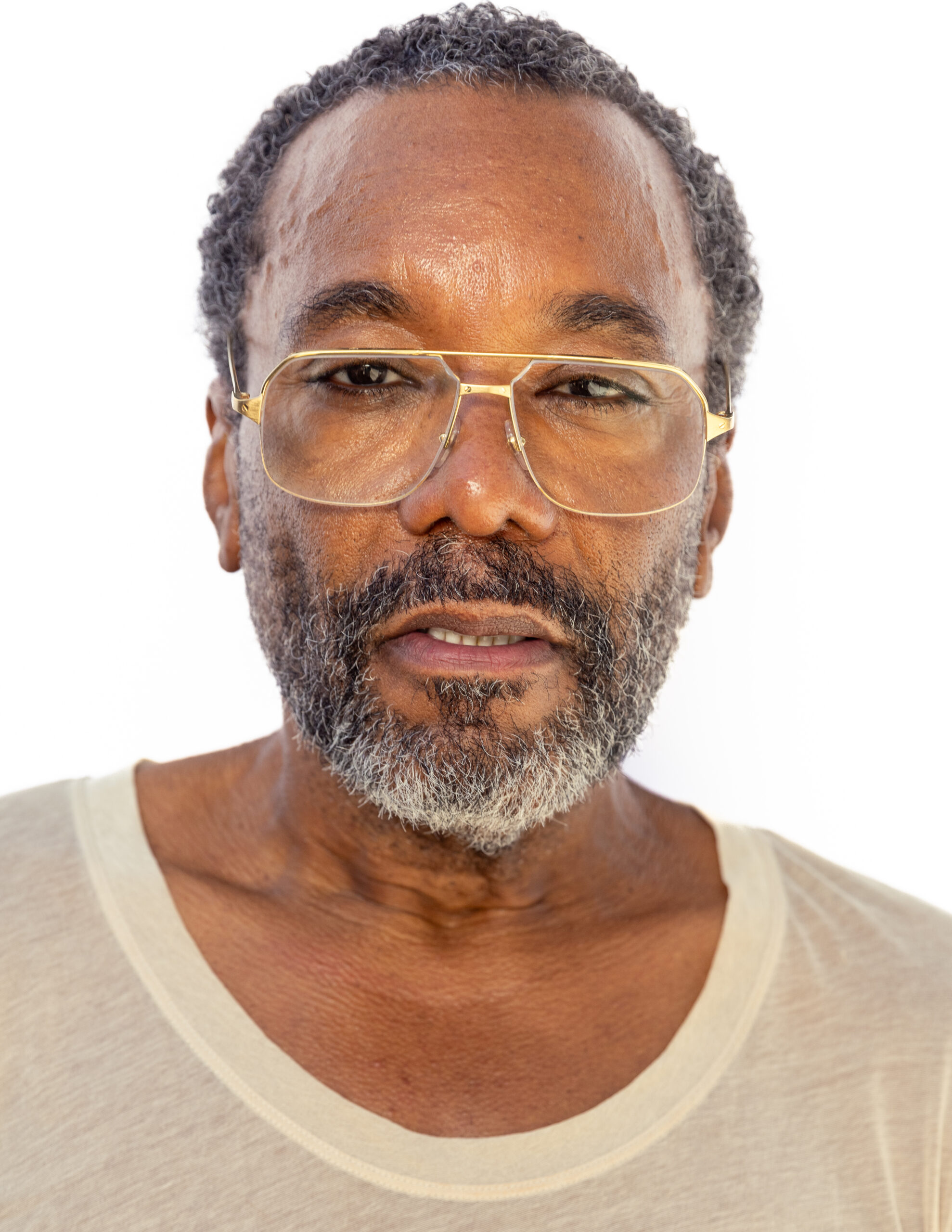

DIRECTOR

“This Is a Fucking Therapy Session”: Lee Daniels, in Conversation With Glenn Close

If you’ve spent any time at all on Twitter this past week, you’ve probably come across an image of Glenn Close, looking positively demonic, delivering what might be the craziest, most obscene line you’ll hear in a movie this year: “I can smell your nappy pussy.” You have the director Lee Daniels to thank for that one. In his new film The Deliverance, the 64-year-old Academy Award nominee gets campier than ever, tapping Close and Andra Day as mother and daughter in a supernatural trip about trauma, abuse, and exorcising family demons, literally. But how, Close wondered, did Daniels develop his singular moviemaking sensibilities? It all started at the Philadelphia Library, where a young Daniels came upon Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? “At eight years old, I read it,” he told Close when the two got together in Los Angeles last week just after their movie hit Netflix. “But the scary part is that I understood everything at eight.” Below, the film veterans enjoy a wide-ranging conversation about the movies that shaped them, filmmaking as a kind of therapy, and forging a path for Black directors when there wasn’t one.

———

GLENN CLOSE: I’m going to start with this one, ‘cause I think it’s a really interesting question. Your films often address complex social issues and feature strong, multidimensional characters. Can you talk about some of the filmmakers, artists, or experiences that have influenced your work?

LEE DANIELS: Yes. One of the first films I saw that really threw me for a loop was Mandingo. Did you ever see that movie, Mandingo? You should see it.

CLOSE: I don’t know if I did.

DANIELS: It stars Perry King. You know who Perry King was? Perry King was a beautiful television actor that dipped his toe into film. It’s a must-see for you. It’s this interracial love story about slavery. Can we Google real quick who produced and directed Mandingo? It was provocative. It was about slavery. It was about sex. It was about debauchery. It was a mixed-race version of Caligula.

CLOSE: Wow.

DANIELS: Except it was about slavery and it was just erotic.

CLOSE: It was that raw?

DANIELS: It was erotic. Okay, directed by Richard Fleischer and produced by Dino De Laurentiis.

CLOSE: Wow. So when did you decide that you yourself wanted to make movies?

DANIELS: Well, I didn’t know what it was. I came along pre-Spike Lee and post the Black Exploitation Era, post Shaft, post all that. So I didn’t know that there was such a thing as a Black director. I didn’t even know this was what a director meant. I walked into the Philadelphia Library and the spirit drove me to the theater section. I was eight years old and I saw Liz Taylor and Richard Burton on the cover of a book called Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? At eight years old, I read it. I took it home, and I had everybody on the stoops, because I lived in the projects. I had my sister and my cousin and my neighbors reading Martha, George.

CLOSE: And you were eight?

DANIELS: Mm-hmm. But the scary part is that I understood everything at eight. My dad wanted me to be a lawyer, because he wasn’t a lawyer; he was a cop, inevitably killed in the line of duty. And that’s sort of—

CLOSE: That’s really interesting, how you were actually moved by story and character before you even thought about being a movie director.

DANIELS: Blown away by story.

CLOSE: I know it’s something you really, really struggled with when you were editing The Deliverance, intertwining horror with deep societal issues. How did you balance the supernatural with real-world struggles?

DANIELS: I still don’t know. I think in my head it was a drama until it wasn’t. From listening to audiences, I knew that I was on something completely different, a different type of filmmaking, because the audience wanted horror from the beginning and I wasn’t giving it to them. But I didn’t care what the audience wanted. I needed to make sure that they understood the relationship between the mother and the daughter and everything that was going on in the house. I knew that Alberta was going to die, and I really needed to feel what that was going to feel like. And how could you feel anything if you’re more worried about the boogeyman up front? So it was a hard needle to thread. I think I’ve threaded it. For some, it’s still not going to be enough, but I’m really content with it.

CLOSE: The thing that I thought was genius when I read the script was how it’s absolutely possible that Ebony’s beating the kids, because they’re all trying to break out of cycles of abuse. So the fact that it’s actually the demon is incredible. I just thought it’s a kind of physical demonstration of something very spiritual and metaphysical—that you get beaten up by the dark.

DANIELS: Listen, that was the hardest part for me. They kept telling me tension, scary tension, in the beginning. I’m like, “No.” I’m listening to the audience and listening to Netflix’s notes about how they want tension in the movie. But the person in the house was Ebony. That’s who you were supposed to be afraid of. But they didn’t understand the concept. So I think that part of making them comfortable was sort of that give. And I gave as much as I could give.

CLOSE: How much is your own struggle evident in the movie? Because I was very aware working on the film of how you were on a journey. You were, I would say, changing your life.

DANIELS: I don’t know. I came to Hollywood and said, “Okay, let me just go for my dreams.” There weren’t any Black directors. There weren’t any. So I was determined to forge my own way because how could anybody take me seriously? My path is such a unique one. I went to every studio and I was pitching and everything.

CLOSE: I don’t know what it must have been like to be in this town with nobody forging the way.

DANIELS: You have to understand, I was openly gay. And I was laughed out of offices. They were just like, “Who is this person?” But never once, except with this film right here, has any film of mine been anything but independently financed. And after my first Oscar with Halle [Berry, for Monster’s Ball], I knew how to cast. But I didn’t know how to hold a camera. So I knew how to direct actors, but I didn’t know what a production designer did. So learned it from that film, from letting Mark Forster direct it. knew that he had a sense of what it was. But I worked with the actors because I was directing theater. I was directing these little one-acts at Zephyr Theater on Melrose. So I worked intimately with actors. But all of my films have been independently financed, where I’m writing the check, I’m yelling “action!” But I make my money back because I sell them, and I make good money when I sell them. but I’m not a studio guy at the end of the day.

CLOSE: It’s incredible. That’s deep to unpack.

DANIELS: I unpack it through the work.

CLOSE: I have a theory that all art really worth something comes out of a sense of outrage.

DANIELS: Oh, yeah.

CLOSE: It becomes your engine. You can turn it into something positive.

DANIELS: Well, people don’t understand. Like, what did Precious come from? I could never answer for the life of me. I couldn’t figure it out. Then I realized it was my story, you know what I mean?

CLOSE: Do you think you’ll ever be content?

DANIELS: You know the answer.

CLOSE: Because I’m the same way.

DANIELS: Come on, Glenn. Think of something more original, baby.

CLOSE: Do you feel a responsibility to make films that push boundaries? And if so, how do you manage the pressure that comes with that?

DANIELS: I don’t feel a responsibility anymore. I could retire if I wanted to, because I feel that I’ve been responsible for the first Black actress receiving the Academy Award. I’ve been responsible for the first Black writer receiving the Academy Award. I’ve been responsible for a television show that changed the landscape of African-American Cinema. So I’m okay. My responsibility is to make sure that young, queer kids of all colors understand their power. That’s the only responsibility I think I have.

CLOSE: So how do you manifest that?

DANIELS: That’s why I did that play.

CLOSE: Talk about that, because people might not know what that play was.

DANIELS: That play was called Ain’t No Mo’. It was my first time on Broadway and I was trying to raise money. I didn’t understand. I found it interesting that the first time I went into the theater, I assumed that it worked the way that cinema worked. But I didn’t understand it.

CLOSE: And Broadway’s so expensive.

DANIELS: Rosie O’Donnell said, “Lee, don’t do it. Don’t do it.”

CLOSE: That’s why people are trying to find warehouses and empty restaurants to stage their shows.

DANIELS: Is that what they’re doing now?

CLOSE: Yeah.

DANIELS: Did You see Oh, Mary yet?

CLOSE: No.

DANIELS: I can’t wait for you to see it. You’re going to love. But I think you said something very powerful that I think is going to change the landscape of Broadway. They have overpriced themselves. And if what you’re saying is correct, if they’re looking at warehouses and restaurants, it’s a new day. I remember seeing Dream Girls for the first time and it just changed my life. I snuck in the back of the theater and I’d never seen Black people. I was like, “What is this?” And I said, “This is what I want to do.” It was Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and it was Dream Girls. I said, “Oh, wow, this is what I want to do.”

CLOSE: What you wanted to do was—

DANIELS: Direct.

CLOSE: Direct.

DANIELS: I was destined to do that because I was always searching for the truth. I was always searching for true truth, Glenn. And to flip it back to you, the work that you do is so true. You cannot fuck with Black people and the truth. They know the fucking truth when they see the fucking truth. And what I’m learning is that your Black audience is probably bigger than your White audience. When they respond, “I’ve never seen her like this before,” I know I won a little bit.

CLOSE: Wow. Thank you.

DANIELS: Isn’t it great? But we can’t work together again, because I don’t know how you top that.

CLOSE: Well, I never know what I’m going to do next, but I know it has to be different.

DANIELS: You are always on the search for something different. I can’t sit. I can’t be pegged.

CLOSE: You don’t repeat yourself.

DANIELS: Because it’s dangerous. It’s really dangerous.

CLOSE: But it’s also boring.

DANIELS: But sometimes you need it for the money. That’s when they get you.

CLOSE: How do you reconcile the often bleak realities you portray in your films with your personal outlook on life? You’re making a movie like Precious, that’s bleak and hard, how does that affect your life?

DANIELS: It doesn’t affect my life at all. It’s therapeutic for me. It gives me joy to see what’s in my head, what I’ve experienced on the screen. Monique didn’t understand it. She’s like, “Why are you laughing?” And I just said, “I’m sorry. It’s therapy for me.”

CLOSE: That’s great.

DANIELS: I don’t know, is that sick? Maybe we should cut that one, but I don’t know.

CLOSE: No, I liked hearing it. Being on a set with you, I felt I was walking into a vital creative space every day. It was shimmering with your vision, with what you had in your head. It was highly chemical. I’ve always thought of casting as putting together some sort of chemical mixture. Everybody affects everybody else, but you’re the one who affects everybody more than anyone, so how do you keep the engine going in a situation like that? If you’re in the middle of making a movie that’s highly emotional, very challenging, do you ever come to a point where you say, “I don’t know if I can do this”?

DANIELS: No, never. Because that’s not an option. Giving up is not an option. And I think that when you’re in these dark places, there’s something about survival that kicks in. So I transfer that to the work. The only thing that I was upset about, I’ll tell you, because it was the one time I didn’t listen to my instinct, was having that man kiss you. That’s the only thing.

CLOSE: Isn’t that funny? I think the same thing.

DANIELS: I’m so fucking mad at myself. I was like, “This is ridiculous. Why am I treating her like Glenn Close?” But yet, I have such reverence for you as an artist. You’re a part of the fabric, the fundamental fabric. And I knew what I was going to have you doing. I was like, “I can’t push it too much.” But you’ve got to pick your battles. Does that make any sense at all?

CLOSE: It does. You chickened out, man.

DANIELS: I did. I know. This is a fucking therapy session. Jesus Christ.