That Time Laura Dern’s Mom Brought A Lollipop To A David Lynch Abortion

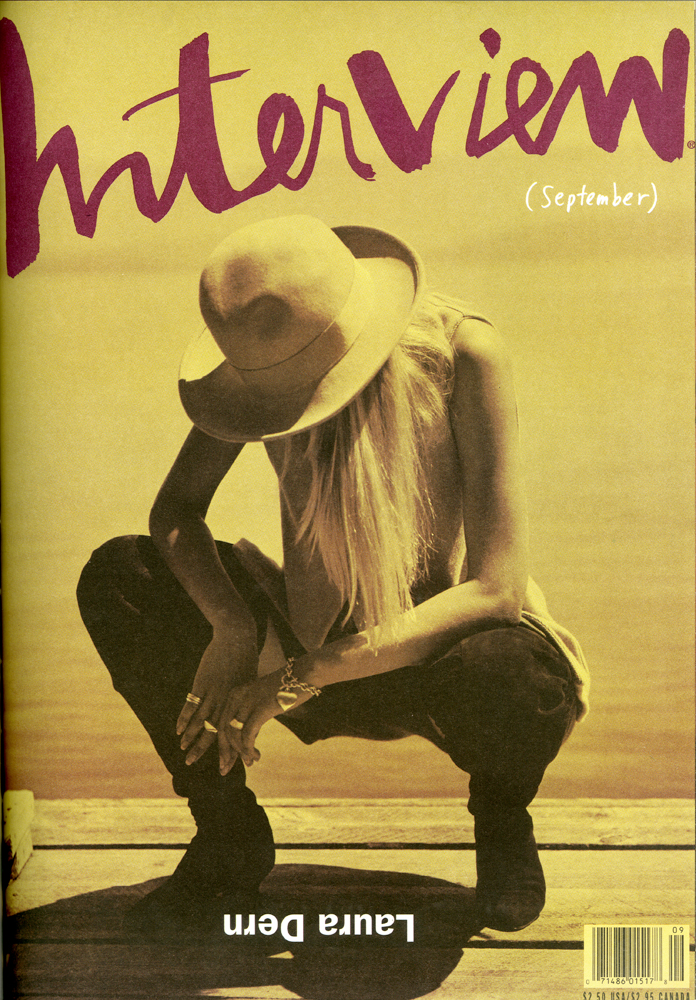

That Time When is Interview’s weekly trip through the pop-cultural space-time continuum, where we return to some of the most overlooked moments from issues past. In this edition, we revisit our September 1990 cover story featuring the beloved actress Laura Dern, in which she discusses learning a bit about her mother in their first scene together on the set of David Lynch‘s Wild at Heart.

The dawn of the ’90s found two of cinema’s children looking to join the adult’s table: Nicolas Cage, the nephew of Francis Ford Coppola, and Laura Dern, the daughter of Bruce Dern and Diane Ladd. With Wild at Heart, David Lynch gave them the seats. At first glance, the then-23 year old Dern would seem like a Hollywood golden girl, but her nascent filmography revealed a set of roles shaping up to be as strange as her parents’. Her father cut his teeth in some of the darkest movies of the 1960s, from Robert Aldrich’s thriller Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte to Sydney Pollack’s melodrama They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Ladd, meanwhile, appeared in the grim, era-defining films of Roman Polanski and Martin Scorsese. Laura’s early roles reflected an inherited desire to lean into darkness. In David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, Dern famously prophesies in a quiet church parking lot: “Until the robins come, there is trouble.” It was the start of a fruitful partnership with the twisted director; in her 1990 Interview cover story—her second for this magazine—Dern told the artist Gary Indiana about Wild at Heart, in which she starred opposite her mother for the first time. There is, of course, little that is more complicated than a daughter’s relationship with her mother.

GARY INDIANA: In Wild at Heart, it’s quite uncanny to see you and your mother playing daughter and mother. The resemblance is extraordinary.

LAURA DERN: I think it’s a little frightening, given the characters. It’s always been a desire of mine to work with my parents, so this was a wish come true. The first day we did a scene together I came down the stairs and my mom pointed that finger at me: “Don’t you dare talk to that boy again!” You know, I’ve seen that finger for twenty-three years. And I started laughing, she started laughing, then the whole crew broke up—in that moment they all knew that she and I had been there before. On the third day of shooting, I saw her getting made up. She was certainly in her glory, because she’d done the bathroom scene, she had such a wild outfit on, she was having eyeliner put on, and Nic Cage came up behind me and whispered, “Look over there, that’s your mom.” It’s comfortable to be on a set with her—I’m used to that, but she blew my mind when I saw the movie. We were in so many scenes separate from each other, neither of us knew what the other was doing.

INDIANA: She’s bigger than life in Wild at Heart.

DERN: Every little thing she did—her nails, her different wigs. David and I had lunch the day after she finished shooting, and I asked him how her last scene went, and he said, “Who would have thought your mother would turn out to be the ultimate David Lynch actor?” At one point she was supposed to be watching my abortion, in that flashback where I’m on the table. David said, “We’ve got to do something different, Diane. We need something here.” And my mom got a lollipop and started waving it in my face, like, “Honey, if you’re good you’ll get a lollipop.” In the middle of an abortion, your mother offers you a lollipop? She came up with weirder ideas than I would have. Obviously, we’re lucky we have a good, healthy relationship—my God, can you imagine if that really was our relationship, trying to work with that person?

INDIANA: But was it sort of a nightmare recasting of your relationship?

DERN: Actually, not at all. You know, there was a television show called The Innocents of Hollywood. Brooke Shields is a friend of mine and she did one of the introductions to it, and she called me and said, “I think you better check this out.” And on this show they talked about parents who’d ripped off their kids. One of them said, “My mother stole $300,000 from me as a child.” Well, my mother opened a bank account for me when I made $60 on my first day of work as an extra. She’s that kind of mother. But God knows what people will say when this movie comes out. It sounds like a cliché, but she’s really one of my closest friends, and so’s my dad. He and I weren’t very close when I was younger, but now we’re best friends. I do think my mother was a bit overprotective, not in any sordid way, but just normally. She certainly might say to me, “You know, Laura, I don’t have a good feeling about that guy. I don’t know if I want you to go out with him.” But if you’re asking, “Would she try to fuck him in the bathroom and then hire a hit man to kill him?”—I think that’s a little further than she’d ever go. It’s interesting to talk to my mom about her character, because she sees her as a mother who’s just trying to protect her baby from a bad boy. I think that’s why it works so beautifully—she has conviction about what she’s doing.

Later, Dern touched on the legacies of other women, this time fictional, towards whom she looked for inspiration.

INDIANA: Are there any great women characters in literature that you’d like to play? I see you in William Faulkner roles.

DERN: Wouldn’t that be beautiful? There are characters I love that are such martyrs, and then ones with a comical side to them, Oscar Wilde sorts of characters. But Faulkner or even Fitzgerald—if I were a man, I’d love to play Dick Diver. One character I’m fascinated by, and would love to see done correctly, is Hester Prynne. There’s a lot more to that story than we’ve seen! It has so much to do with AIDS, with any issue—South Africa, anything. It’s about judgment and fear in a puritanical society. That a man would be so afraid that he’d lose control—that’s what it’s about. Hester would be really exciting. Or a movie character like a Mr. Smith goes to Washington but a woman, someone who’s an innocent and sort of wins over the system. I love people who fight the system.

It wouldn’t be long until Dern fulfilled her wish to portray a radical system-shaker. In 1996, she starred in Alexander Payne’s Citizen Ruth as a pregnant woman who finds herself at the center of the abortion debate—once again performing alongside Ladd, her real-life mother (though this time, she didn’t bring a lollipop). More recently, Dern has taken her own step into the maternal, playing the pant-suited working mom Renata Klein in HBO’s Big Little Lies. This year, in Greta Gerwig’s adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, Dern reestablishes Marmee, the girls’ mother hen, as a woman intent on nurturing her daughters’ souls and ambitions despite various challenges. In short, Dern’s Marmee minimizes constraints, just like Dern’s own mother. From Little Women to Marriage Story, Dern has continued to probe the fringes of systems as characters who fight in their own—sometimes quiet, sometimes much louder—ways.