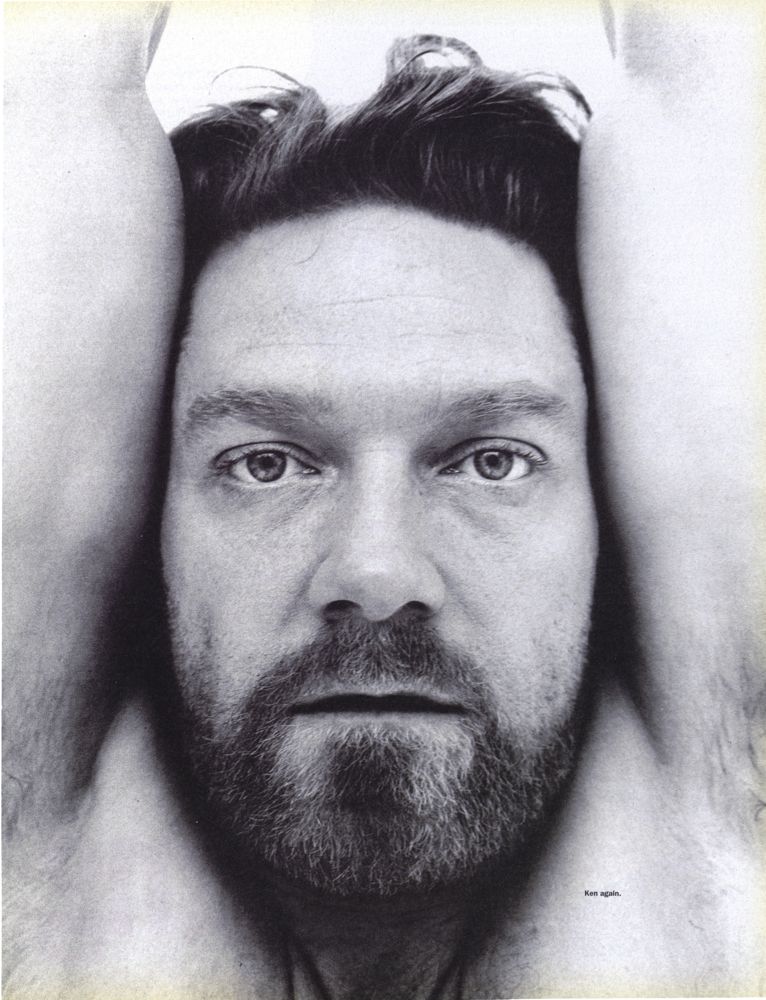

Kenneth Branagh

It’s a monster! Kenneth Branagh unveils his biggest creation yet—Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Kenneth Branagh might seem like an unlikely choice to helm Francis Coppola’s $44 million production of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, companion piece to Coppola’s own Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). Branagh’s four previous films as director have not distinguished him as any kind of auteur, yet maybe Hollywood prefers a tenacious jack-of-all-genres: Henry V (1989) is a gripping war film, Peter’s Friends (1992) a warming English Big Chill, and Much Ado About Nothing (1993) a lissome summer romp; only Branagh’s Hitchcock homage, Dead Again (1991) has suggested that this unstoppable Renaissance man might have been better off sticking to the boards.

If Branagh has adhered to the spirit of Frank Darabont’s florid but genuinely chilling screenplay, the most faithful adaptation yet of the Romantic masterpiece conceived by Mrs. Shelley at the Villa Diodati, near Geneva, in June 1816, he may still prove a powerful visual stylist. Branagh himself plays Victor Frankenstein, Robert De Niro is his equally tortured Creature, and Helena Bonham Carter is Elizabeth, love object of gothic cinema’s most infernal Oedipal triangle.

GRAHAM FULLER: Why do you think that Francis Coppola approached you to direct this version of Frankenstein? Do you think he sensed that your appreciation of the mythic resonances in Shakespeare would lend itself to the Frankenstein myth?

KENNETH BRANAGH: I never asked him, actually. I was too nervous to, in case he said, “I’d never heard of you. Somebody else suggested you.” Certainly, at this end of things, I’ve noticed that the subject has a Shakespearean scope and grandeur. Frankenstein feels like an ancient tale, the kind of traditional story that appears in many other forms. It appeals to something very primal, but it’s also about profound things, the very nature of life and death and birth—about, essentially, a man who is resisting the most irresistible fact of all, that we will be shuffling off this mortal coil. It was sent to me as I was rehearsing a production of Hamlet, and it seemed to me that the two things were linked. Hamlet and Victor Frankenstein are each obsessed with death. Hamlet’s whole story is a philosophical preparation for death; Victor’s is an intellectual refusal to accept it.

FULLER: You had Frank Darabont revise the original script. What changes did you ask for?

BRANAGH: I asked him to include all those events and characters in Mary Shelley’s novel that hadn’t been together in the film. One of the main themes in the book is the idea of a happy and united family being destroyed when Victor’s mother dies of scarlet fever after nursing her adopted daughter, Elizabeth, through it. We have Victor’s “more-than-sister,” as he describes her, a strong presence in the Frankenstein story as Mary Shelley was in the life of Percy Bysshe Shelley, whom I think Victor was partly based on. This was something Frank was less keen on, but I felt very strongly that Mary Shelley and, indeed, her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, were tremendous heroines who should be represented as Mary Shelley would have written them were she writing now, instead of within the literary conventions of the early nineteenth century.

FULLER: Mary Wollstonecraft died a lingering, painful death after giving birth to the future Mary Shelley, who lost a prematurely born child in 1815, a year before she began the novel. So when Shelley describes Victor’s laboratory as “a workshop of filthy creation,” you get the sense that she’s describing the womb. Your movie is thick with weird natal imagery. Were you drawing on the tragedies in the Shelley family as a kind of metaphorical backdrop to the creation saga?

BRANAGH: There are vaguenesses in the book that allow for the readers’ imaginations to come into play, like the creation sequence itself, an in order to fill those gaps and build the psychological details of the character, we did go to the Shelley family. I think Mary experienced great guilt in giving birth to her children, only one of who lived to maturity. She was surrounded by images of death—Percy wooed her on her mother’s tombstone in Old St. Pancras churchyard—and that closeness to the reality of death fed the excitability and passion and feverish imagination that ran through her entire household. Our screenplay was infused with that. We also tried to make as many explicitly sexual birth images as possible. In Victor’s lab, we have a huge phallic tube with shoots electric eels at an enormous womblike sarcophagus. When the Creature is born, the amniotic fluid it’s cooked in spills out into this awful delivery room. It’s a low-tech version of a very ugly birth.

FULLER: did you explore the Promethean aspects of the novel?

BRANAGH: I think Victor’s desire to realize his hubristic obsession of creating life—his fight with God, if you like—is very powerfully represented. There are strong image of fire and ice, heat and cold, blood and butchery throughout the book, and we tried to match those in the film. There’s an almost operatic battle between Victor and his own creator to win the battle of creation.

FULLER: Your film draws on pinnacle moments in James Whale’s Frankenstein [1931] and Bride of Frankenstein [1935]: You have Victor’s little brother killed by the Creature; there’s a pathos-laden interlude with the blind grandfather; and the reanimated Elizabeth goes berserk.

BRANAGH: The re-creation of Elizabeth is not in the novel, but it was impossible to resist the temptation to have Victor bringing back to life the person he loved above all. It’s our major departure from Shelley, yet it seemed to make psychological sense. It may be that our film is too packed with incidents, and that Whale was wise to reduce the first film to the idea of building a monster and the second on to making him a mate. But we wanted to see how much we could disturb people. Hopefully, when audiences see Victor about to reanimate his dead love, they’ll go, “Oh no, surely he won’t, he can’t; oh my God, he will!” It’s a grotesque sequence in the film, and yet it’s strangely moving in a way that’s different to Whale’s high camp.

FULLER: As a director, knowing that you had to make the Creature believable, how did you get beyond De Niro’s icon status?

BRANAGH: By working specifically on his character. We wanted to make the creation of the Creature as realistic as possible within the period, so we talked about how they would have stitched limbs together at that time. We talked about which parts of his body would be missing and why they would be missing. Would the corpse that the body is based on have been previously diseased, and if so, where? We looked at a color dictionary of facial reconstruction, plastic-surgery books, and crime-scene photographs, so right from the start we were working closely with Bob, as opposed to being in awe of him as someone bringing extra baggage. Just before he finished, he agreed to talk to the documentary unit that was producing a promotional featurette for us as long as I did the interview. I was happy to do this after a year of working with him, but when I sat down in front of him, it was then that I became tongue-tied and awestruck. I was very glad it hadn’t occurred until that point.

FULLER: I know Coppola had an AIDS metaphor in mind when he made Dracula. There seems to be one here, too, in the cholera epidemic and Victor’s desire to find a cure for all illnesses.

BRANAGH: Yeah, I think there are some parallels. Through Victor, Mary Shelley talks about the pioneering work of brilliant scientists, which allows us to lay out a moral dilemma where not doubt, behind closed doors somewhere, a cure for cancer or AIDS is being discovered, but with some kind of price to pay. An image that came to mind was Einstein and Oppenheimer being so caught up in the excitement of solving the mathematical equation that would enable the splitting of the atom that, had they known what it was going to lead to, they might have thought again.

FULLER: Joyce Carol Oates describes Frankenstein as a parable about the dangers of denying responsibility. What do you think is going on unconsciously?

BRANAGH: Instead of being a very small think that one can pick up and cuddle and cosset, the Creature is a huge, fully formed thing that, because of the recklessness of its creator, is endowed with a whole series of powers that make it, through no fault of its own, incredibly dangerous. Nevertheless, it’s as similarly dependent on the creator as if it were tiny and cherishable. This underlines notions of scientific, political, and social responsibility. I think that this disadvantaged, hulking brute Victor has created holds the mirror up to nature and says,. “Here is an aborted, perverted man who in his very being is an image of what we should be avoiding.”

FULLER: What about the sexual elements? There’s obviously a fear that the creature is going to violate Elizabeth. Is it also implied that he rapes Justine Moritz, the housekeeper’s daughter?

BRANAGH: We imply that he is very excited by here. In the book, Shelley alludes briefly but potently to the idea that if the Creature were to have companionship, it would be at the risk of a whole tribe of these being peopling the earth. This is how Shelley nods obliquely toward the idea of sex, though I think she’s quite titillated by it and goes to some pains to describe the size of the creature, to brilliant comic effect. She was aware that if this Creature is eight feet tall, as he is in the book, presumably he’s got an enormous plonker, and that might be tremendously exciting to whoever was on the receiving end of it. It creates a sexual jealousy between Victor and the Creature that is quite explicit in the last sequence of our film, when Elizabeth is re-created. Indeed, one is forced to think that the Creaturess might be better off with the Creature than with Victor.

FULLER: What was your guiding principle in composing and framing the film?

BRANAGH: I wanted to create a fairy-tale world of primary colors, of large rooms, of space and size, of big buildings, of big nature. I wanted to have a sense of the presence of enormous natural forces, and of humans being small in relation to all these things. I want the audience to be there in Victor’s fevered imagination and I want them to catch the bug, so the camera moves a great deal. The camerawork is often expansive and bright, but then we go to ingolstadt, where the plague is, the images are dark and miserable and sweaty and grimy. Shelley herself made those contrasts quite broad.

FULLER: Did unexpected metaphors emerge?

BRANAGH: It’s become very religious in a way. There’s a lot of Christ-like imagery in it, and Victor’s laboratory, I’ve suddenly realized, looks like a holy cathedral. It seems very sacrilegious, ungodly. You’re really aware that you’re watching a man who’s shaken hands with the devil, and there’s something diabolical in there that was not conscious but just seeps through the entire picture.

FULLER: Did you get right to the core of horror?

BRANAGH: When Victor decides to re-create his dead bride in this picture, it’s so horrific as to be almost unbearable. When he dances with her, it’s impossible to conceive what’s happening, because of your emotional investment in their relationship. It’s your worst nightmare come true before your very eyes. It’s more than just being frightened by that the Creature looks like, more than just being scared because something emerged from the shadows when you weren’t expecting it. Although the film obeys some of the horror genre rules, it evokes a primary repulsion of something that is almost beyond the imagination and yet is sufficiently close to what’s possible as to be profoundly disturbing. I will not be sad to say good-bye to this project, because it’s quite a hard thing to carry around in your system for two years. After Frankenstein, I feel as if I want to make a film about somebody having a nice cup of tea.

FULLER: Did the movie ever become your own personal monster?

BRANAGH: At times it did, yeah. It’s a big thing and it demands massive amounts of attention, and having come this far and having had the amount of freedom I’ve had to work on it, it’s not possible to walk away from it without feeling that everything that you wanted to say or do in it has at least been attempted. So to that extent it remains an obsession.

FULLER: You’ve directed five movies now, and yet I get the sense that you never really intended to be a film director.

BRANAGH: No, I didn’t expect that to be the case. I am genuinely surprised by it. I know Frankenstein has squeezed the last bit out of me for a while.

FULLER: Have you laid the ghost of the hubris that the British press reckoned was your lot?

BRANAGH: I really don’t know. I guess if you hang around long enough and continue to do the best work you can, people will at least get used to you and take aim at someone else. Somehow I know there was something so right about my doing Frankenstein and taking so long over it that I’ve probably been laying some ghost inside myself. It was a very necessary job for me to do, but it’ll take some time to recover from it.

THIS ARTICLE ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN OUR NOVEMBER 1994 ISSUE.