Kantemir Balagov Films Women Who Survived, and Have to Live

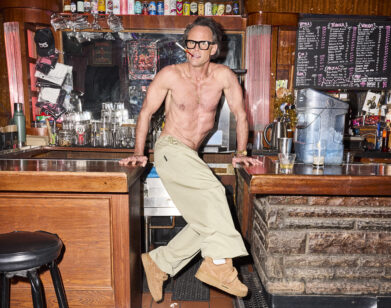

Photo by Kira Kovalenko.

Chechnya is a republic marked by silenced outcries—the acting head of the Russian Federation, the Vladimir Putin-approved Ramzan Kadyrov, has violently stifled supporters of Chechen independence, denied the very existence of Chechen homosexuals when accused of detaining and torturing gay men, and worked to limit female presence in the public sphere for his ongoing fifteen years in a position of power. Kadyrov became First Deputy Prime Minister in 2005; in his first active year, he halted the operations of the largest nonprofit humanitarian organization in Chechnya. The director Kantemir Balagov, whose film Beanpole won Best Director in the Un Certain Regard category at last year’s Cannes Festival, was born in 1991, hours away from Chechnya. This was the year of the first Chechen War, precipitated by the question of Chechen sovereignty. In this war, Kadyrov fought against Russian nationalists; he had not yet become one himself.

Now 28, Balagov grew up in the Northern Caucuses, adjacent to the first and then second Chechen Wars. He abandoned a university degree in economics to study under the master director and devotee of Andrei Tarkovsky, Alexander Sokurov, who resisted Soviet censorship. Sokurov’s student is as committed to an all-encompassing vision of life, mystifying and never simplified, as his teacher. Balagov’s first film, Closeness, set in his hometown, premiered in 2017 to prizes and acclaim for its portrayal of care turning curdled, perverted when tribal identity becomes a guiding ethical code. One doesn’t have to think too hard to guess where he became fascinated by the tension that results when love and rigid loyalties clash.

Beanpole ventures further from Balagov’s lived experience, but continues to question the fallout when one is asked to unlearn the parameters that have dictated their existence in the world. In the slow-burning psychological study, former soldiers Masha (Vasilisa Perelygina), and Iya (Viktoria Miroshnichenko) struggle to live free of the constant threat of destruction for the first time in years—it is 1945, and the Siege of Leningrad has finally ended. As the women attempt to untangle the relationship between their traumatized minds and bodies, fighting against their own psychic rifts to project the possibility of life into the future, Balagov creates a paradoxically vibrant masterwork. The film unfolds to the destruction of both its characters and its audience. With the help of a translator, Interview spoke to the Beanpole director about his mission to cinematically articulate a largely disregarded experience: that of the women who survived an attack orchestrated to eliminate that possibility.

———

BESSIE RUBINSTEIN: Beanpole takes place in the aftermath of the Siege of Leningrad, at the end of World War II. According to Hitler’s plans, Leningrad was meant to be completely destroyed—how do you go about portraying people who weren’t intended to have existed?

KANTEMIR BALAGOV: Okay, so this is a really cool question. I have been thinking about this, and I have come up recently, quite recently, with an idea that when we talk about cinema, when we work in cinema, we’re dealing with ghosts. So at the risk of sounding banal, I always thought about cinema as a tool of immortality. You create something that will never change. But on the other hand, when time passes, these images and characters that you’ve created, they become ghosts.

We didn’t create these characters or imagined this story, but rather borrowed it from the past. Maybe they actually existed, we just don’t know about it. The inspiration was a picture taken by Robert Capa during his visit of Moscow with John Steinbeck, of two girls dancing. So in both of my films, I really wanted to believe that the people I am telling the story about, and the story itself, could have been real. Actual people and the actual events. But you know, honestly I will have to think longer about your question because the question is really good.

RUBINSTEIN: Your first film, Closeness (2017), also looks at the past, though it’s the more contemporary past, 1998, and faces the significance of the Chechen Wars. I was wondering if, when choosing the setting of your films, you’re thinking about how helpful the moment you pick will be in understanding the present?

BALAGOV: I think that I do. For me, the person and the character are the cornerstones of my way of thinking about the story. And theoretically speaking, the film could have been taking place in the contemporary world. It would have been a different war. But I wanted a different timeline, a different period, because there were practical necessities. The belief of people in medicine as opposed to in miracles should’ve been just so. And there were many practical reasons for picking this particular period.

When you speak about Closeness, it’s also very important because the Chechen War was very close to my hometown of Nalchik, and the war itself affected the city and its inhabitants very much because it made them angry and more aggressive, and this strong desire for independence that drove the Chechens to the war, it influenced people who live in Nalchik. It was contagious. So, yes, I can say that I think about parallels between the period I pick and the modern world. But I think more about the characters and their stories.

RUBINSTEIN: Deciphering the present isn’t the primary motivation. To approach this time in history—I read that you were initially moved to portray it by Svetlana Alexievich’s oral history, The Unwomanly Face of War (1985). That novel is about the different experiences that Soviet women had during World War II that haven’t been discussed, and also of course, their residual damage. And I was wondering why you chose to go with an affective story, the immediate aftermath, rather than look at women living through the siege itself?

BALAGOV: This is something that I have been thinking about a lot, and something that actually I stumbled upon when reading the diaries of the siege, and when reading Alexievich’s book about the siege—that it’s actually harder in the aftermath of a war than during wartime. Because during wartime, you have one task. You have to survive. But when the war ends you have multiple tasks, and they’re much harder and much more unbearable. So it was important for me to pick this period.

It’s because the idea that it’s harder for people to live rather than survive is what drove me to think of this period.

RUBINSTEIN: Yes—I noticed that in the relationships in the films, there was this blurring between the idea of people keeping close with each other because they love each other versus keeping close because they need to survive. And I was wondering if you could speak a little bit more about that? The slippage between love and survival in the film, especially between Masha and Iya.

BALAGOV: I think it’s rather complicated for me to explain, because I mean, if we were able to explain it clearly then we probably wouldn’t have made the film.

RUBINSTEIN: [Laughs] Yes, that’s true.

BALAGOV: I think it’s a very complex relationship, and on a very primitive level you can say that they are like yin and yang, and they feed off each other, and they give each other strength at the same time. But to me, it always sounded unnecessary and maybe banal, trying to explain the relationships rather than portray it in all its complexity on screen.

RUBINSTEIN: I see your point. What other research did you do besides Alexievich’s history?

BALAGOV: I looked through a lot of archive photography of the period, and I’ve read books by [Daniil] Granin and [Andrei] Platonov. Personal diaries of people who lived through the siege and through the aftermath of the siege.

RUBINSTEIN: I read that you wanted the composition for Beanpole to be particularly painterly. Besides the photo that was taken in Moscow, which paintings did you look to? Or photographs, or directors with particularly good composition?

BALAGOV: Dutch masters. Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring. Iya—the way she looks during the hospital scenes—it is visually similar. And why I use art as reference is in many ways an influence of Sokurov, who during his time as our teacher, tried in many ways to instill love for the visual arts among his students. And you can imagine that in Nalchik there are not so many art galleries and museums.

RUBINSTEIN: And I feel like whether or not we’re aware of it, so much of our collective imagination about the past is already based in paintings and photographs. So that kind of composition anchors a film in something that we’re subconsciously familiar with.

I want to talk about Pashka. It felt like he was almost being punished for existing, as the only innocent of the film. And his death is never properly mourned. In some ways it’s present for the entirety of the film, but in other ways it seems like it almost never happened. Like a dream. Is that emotional paralysis something that you discovered in the diaries?

BALAGOV: Yes, this is exactly something that I’ve found in diaries and in many ways, that people were surrounded by so much death that this… how to say? The level of empathy, the walls have gotten higher. You have seen so much that not a lot gets through to you anymore.

RUBINSTEIN: A crisis of survival. I know you said you don’t want your film to be searched for explicit meaning or symbolism. Can you talk a little bit about that? About how you think your film should be watched, and if it’s how you think all films should be watched?

BALAGOV: This is not, strictly speaking, correct. What I don’t like is when people ask me to explain to them the symbolism. And for me, the most interesting thing is to hear what people saw in my film, and discover maybe something that I have never imagined. Because they can tell me something that I didn’t think about, something that they saw in the film.

RUBINSTEIN: Allow me this one clarification—do you think that, in Beanpole, the body can be thought of as a physical metaphor for psychological trauma, in addition to physical differences being symptomatic?

BALAGOV: Yes, of course. Psychological trauma as well, but also I see it as the symbol of the trauma that the city survived. That Leningrad survived.

RUBINSTEIN: The scene in which Iya is attempting to conceive the child that she doesn’t want … I was wondering if you had a feeling about what people needed to see and what they didn’t.

BALAGOV: I’m reading a lot of Faulkner right now, and I can say that Faulkner helped me realize my own limitations. What I am comfortable with. What I can do, and what I can’t do. And in some ways, some things that I considered to be amoral before I read Faulkner, now I can—not relate to, but at least understand the undefined explanation.

And in film, this is a process that I would go through together with my characters, because this is something that I have to realize about myself, whether I’m ready to show something like this or not. Would I want to see something like this portrayed on the screen or not? And this is a process that I have to go through with each scene, and my characters and the people who play them, play a significant part in this.

They’re not dolls that I can play with. I try to live through this experience with them.

RUBINSTEIN: The way that you ended the film was… I couldn’t figure out if it was hopeful or hopeless. And I still can’t really figure out what I feel, because I mean, the child they’re talking about doesn’t exist, but Masha and Iya are talking about their future as a family. So I was wondering if you were suggesting that a level of delusion is necessary to continue in such times?

BALAGOV: Yes, exactly. But I can actually say that to be a little delusional is important, not only if we’ve got to live in hard times like in the film, but even in our own everyday modern life. We need to maintain some level of delusion, even though it’s not a great thing, but this might be necessary. Just a little bit.