Jonas Mekas and the Weight of Memory

Jonas Mekas in 1950, with his first Bolex. “It worked fine until 1958 when Ray Wisniewski, a good friend, borrowed it to film the demonstrators of a nuclear ship entering the New York harbor,” Mekas wrote. “During a skirmish with the police he dropped it into the ocean. Being a good swimmer, he managed to retrieve it, but it never worked well again. Around the year 1959 I bought the second Bolex.” All photos courtesy of Spector Books.

———

“There are places and moments during which I feel that I would like to always remain there. But no: next moment I am gone. I seem to enjoy only brief glimpses of intimacy, happiness. Short concentrated glimpses. I do not believe that they could be extended, prolonged. So I keep moving ahead, looking ahead for other moments. Is it in my nature or did the war do that to me? The question is: was I born a Displaced Person, or did the war make me into one? Displacement, as a way of living and thinking and feeling. Never home. Always on the move.”

So wrote Jonas Mekas, the late poet, filmmaker, and godfather of avant-garde cinema. This is the opening reflection of I Seem To Live, the first volume in a collection of Mekas’s copious diaries, currently available through Spector Books. Mekas describes a condition of emotional freneticism brought on, perhaps, in the aftermath of his escape with his brother Adolfas from a Nazi labor camp just six years prior. But Jonas was not simply self-diagnosing a sort of existential attention deficit disorder—he was effectively prophesying the terms by which he would live and work for the remainder of his life: in perpetual motion. Just one month later, he and Adolfas would buy a Bolex 16mm camera together and begin to radically, irrevocably transform the language of cinema.

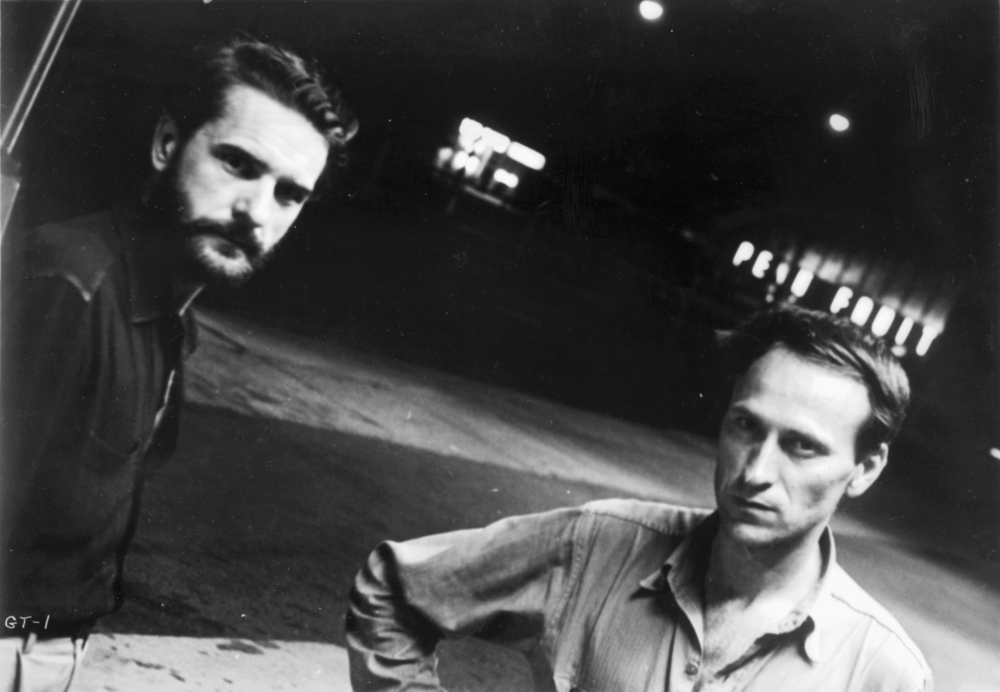

With Adolfas, during the filming of Guns of the Trees.

In the span of just over 800 pages, I Seem To Live encapsulates a great deal of Mekas’s diary entries, written between 1950 and 1969. During those years, Mekas also completed twelve films, culminating in his three-hour opus Walden. That film would be the first in a trio of films that marked a shift in Mekas’s focus—the other two being Reminisces of a Journey to Lithuania and Lost, Lost, Lost where the filmmaker’s frantic gaze seemed to rest more often upon his own life experiences. Through this work, and with the passing of time, Mekas argued, his home movies would transmogrify into art. But as this book shows in intimate detail, Mekas was already fervently documenting such glimpses into his interior life decades before he would put them on screen. Tiresome days searching for work. Museum visits. Walking sleeplessly, endlessly, through New York City’s gray early hours. There are updates, day by day, on the inception of projects such as Film Culture, the groundbreaking magazine founded by the Mekas brothers, and what would become Anthology Film Archives, the cathedral of avant-garde cinema that still stands to this day. Given the scope of the material, one might certainly feel disoriented by the sheer magnitude of the thoughts, images, stories, correspondences, the weight of time is felt concretely here, whereas in Mekas’s filmic work, time is both deeply felt and yet escaped, danced around. It may be daunting, but it’s a welcome addition. This collection is not just a survey of moments from a single life lived, but a work of dedicated portraiture of life itself.

I found myself in his presence once. The day after my 23rd birthday, in October 2018, at Anthology Film Archives. He was supposed to be speaking with a moderator about the impressive longevity of his life, and offer some thoughts about death. But Jonas Mekas did not want to talk about death at all. He said he didn’t spend much time thinking about it. He did say, however, that he often conversed with angels. The conversation ended and he shuffled out of the cinema. I snapped a single photograph as he walked past me. The back of his head. “Always on the move.” He would pass away mere months later. And yet, still, he seems to live.

I Seem To Live‘s launch will be celebrated at Anthology Film Archives on January 26th.

———

With Andy Warhol at The Factory. Photo by Stephen Shore.

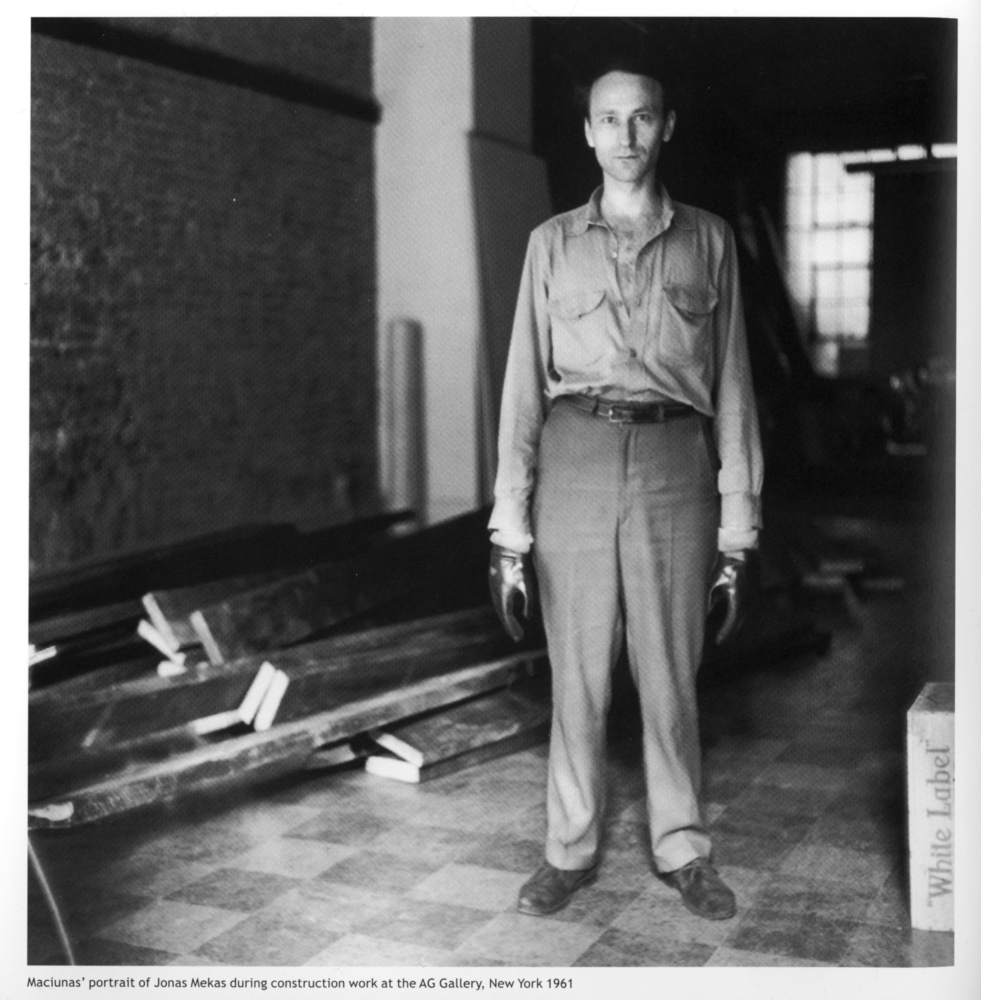

“Helping George Maciunas to fix up his A/G Gallery, 925 Madison Avenue. We had to chip away the thick paint and plaster, to expose the original brick wall. Hard work, a lot of nasty dust…”