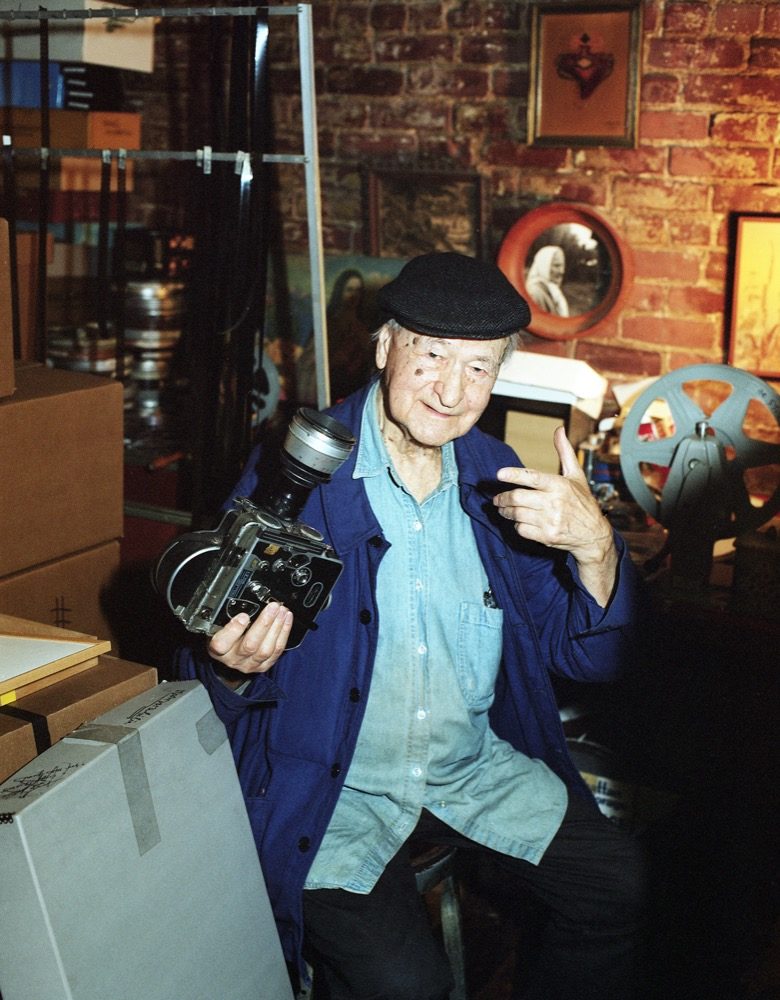

Jonas Mekas: “Nothing is Stopping You From Doing What You love”

Jonas Mekas died this week at the age of 96. The following post collects the best of Mekas’s creative dictums from his book, A Dance With Fred Astaire, published in 2017.

Nobody will tell you to tirelessly, impulsively pursue your dreams without first thinking them through, or formulating a backup plan. But the fearless, avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas has abided by those rules throughout his 94 years. In fact, he gets frustrated at the mere suggestion of tiptoeing around a good idea instead of simply making it happen. “Just do it!” he’ll say.

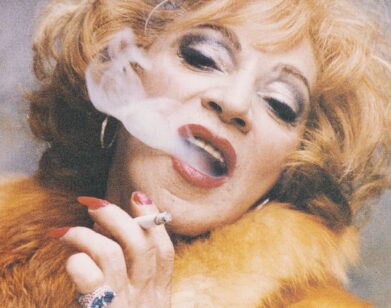

If he had done any planning, he likely wouldn’t have started the Anthology Film Archives in New York’s East Village, collaborated with John Lennon and Yoko Ono for “Bed-In” or with other friends like Andy Warhol, the Velvet Underground’s Nico and Salvador Dalí. Mekas, a Brooklyn transplant by way of Lithuania, will tell you to charge ahead with an idea even if you think it possibly insane. He’s built a career on getting shit done.

If you were to casually flip through the setbacks Mekas has overcome, you’d land at a man with more strength and determination than even the most hardened creatives. Having fled the war in Lithuania, he and his brother were stopped in Germany, where he was admitted into a forced labor camp. Once he landed in America aged 26, he established himself in Brooklyn and studied (briefly) under avant-gardist Hans Richter.

Fast forward several years, and Mekas was sued by a local printing shop for failing to make outstanding payments for the printing of the first issue of Film Culture; then he was arrested for showing Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1963) and Jean Genet’s Un Chant d’Amour (1950). And in spite of it all, he kept making the intimate films he became known for—the “Godfather of American avant-garde cinema”, they call him—on his wind-up Bolex camera.

He’s got a new book, A Dance With Fred Astaire—a compendium of anecdotes from his incredibly full life. Another, I Had Nowhere To Go, talks about his time as a displaced person at Elmshorn labor camp in a Hamburg suburb and the subsequent years in the U.S. Through it all, he has never made any excuses for not doing what he loves—as he says, you just gotta do it.

———

CREATIVITY KILLS

I don’t care about creativity. If one begins with creativity then that’s the end. One just has to do what one feels that one wants to do and what one has to do. If I don’t do [what I want] they will have to lock me up in an insane asylum. [laughs] I must do it! That’s nonsense, this creativity thing. Who cares about it?! You just do it. There must be some passion in it, some intensity in it to be of any relevance to others.

DON’T WAIT FOR MONEY

I had a little job at a place called Graphic Studios helping do camera work for a commercial kind of place, watching the big cameras. So I used my money to live and to publish [Film Culture], but it wasn’t enough. I persuaded the Franciscan Monastery in Brooklyn on Willoughby Street—they had a printing shop—so I persuaded them to print the first issue on a postponed payment. I said the magazine will sell and within a month I [would pay them]. But the magazine came out and no one was buying it, so they took me to court. I never worry. I just do things. There’s always a way to figure it out, so I figure it out. So it’s a big deal they took me to court, I still paid them! They got their money and it didn’t take long.

NO TIME, NO MONEY, NO PROBLEM

There’s a different sensibility, not many people are interested in subtleties of existence of life, of reality. There is no time usually; people have no time for it. They have to work to make money and I don’t care about work or money.

DON’T MAKE A PLAN

My very first feature film Guns of the Trees, I wrote the script and planned but during the filming most of the time I had to forget the script. Never plan. Of course, The Brig, I just went into the play and filmed what was happening, my reactions to what was happening right in that moment. There was no plan. My kind of filmmaking has no plan.In a very personal kind of cinema I do, recording my daily life and around me, you cannot plan, you don’t know what’s coming. I’m not God, all I can do is watch reality and now. To focus, to be very open to what is happening now.

ASK FOR WHAT YOU NEED

I wrote to [Hans Richter], I said, “I came to New York. I’m a displaced person but I have no money. I would like to attend your classes, could I come?” He wrote back and said, “Just come.” That’s it. Only two words. “Just come.” So I came and I discovered that he was not teaching, there were some other Hollywood types that were teaching. But I met some other students that came for the same reasons as myself and we remained friends forever, like Shirley Clarke during one of those sessions in Hans Richter’s class. So I took one term but I became good friends with Hans Richter, and our friendship lasted up until he died. When I began publishing Film Culture in ’54, four years later, he contributed a piece to the first issue.

SHARE YOUR WORK YOURSELF

We created Filmmakers Cooperative, which is still in existence. It was 20 filmmakers, we got together and we established our own cooperative distribution center because nobody else wanted to distribute our films. So we decided we would distribute them ourselves. The cooperative office became my home! My loft! Which was on Park Ave South and 31st Street. It was also home to Film Culture magazine at the same time and my filmmakers and their friends used to come in the evening and screen films and argue; it became a very busy place. That’s where Andy [Warhol] used to come and sit. There were no chairs so he sat on the floor, and there were always 10 to 15 people every evening watching films and at some point Andy began coming.

BE NICE TO EVERYONE

I needed a ticket taker [at the Charles Theater on Avenue B]. So I hired Jack Smith, that’s how I met him! Somebody said, “I have someone who needs a job: Jack Smith.” I said, “Okay, we’ll hire him as a ticket taker.” [laughs] I had to fire him two weeks later. He was very scatterbrained. I couldn’t have kept him, the owner insisted that I fire him. So then I got somebody else who was very good and whenever he passed the box office he used to give me a little paper slips with jokes. He was testing jokes on me. Then later I discovered he was already one of the writers and editors of Mad magazine, but he became publisher and editor of Mad. [laughs]

EVERYTHING WILL BE ALRIGHT

Why do it unless you feel you need to do it! And if you feel you need to do it, even if you don’t know yet how and what will come out, then you have no problem because you will still be doing it; and since you really are doing it from passion, it will come out okay. I think it will come out okay and the material will dictate it’s shape and form, do it and then when you have all the material there, look at it 10 times and it will become clear. It will take it’s own shape.

ACCIDENTS HAPPEN

I began filming in 1950 a few months after I landed in New York and I could get my first Bolex but since I did not know, I had scripts written I had several little scripts that were sort of poetic, they were not normal scripts. But I was not sure so I just kept filming; I wanted to master the camera, to see what the camera could do. Since I got involved in Film Culture then later in The Village Voice, I never had much time, no long stretches of time, I just kept filming in little pieces. I thought I was practicing, but when I began looking at what I had, I realized it was like keeping a diary. So I just continued working that way! [laughs]

A DANCE WITH FRED ASTAIRE PUBLISHED BY ANTHOLOGY EDITIONS AND I HAD NOWHERE TO GO PUBLISHED BY SPECTOR BOOKS ARE BOTH AVAILABLE NOW.