leading man

Beyond Jon Bernthal’s Macho Exterior, There’s a Gooey Center

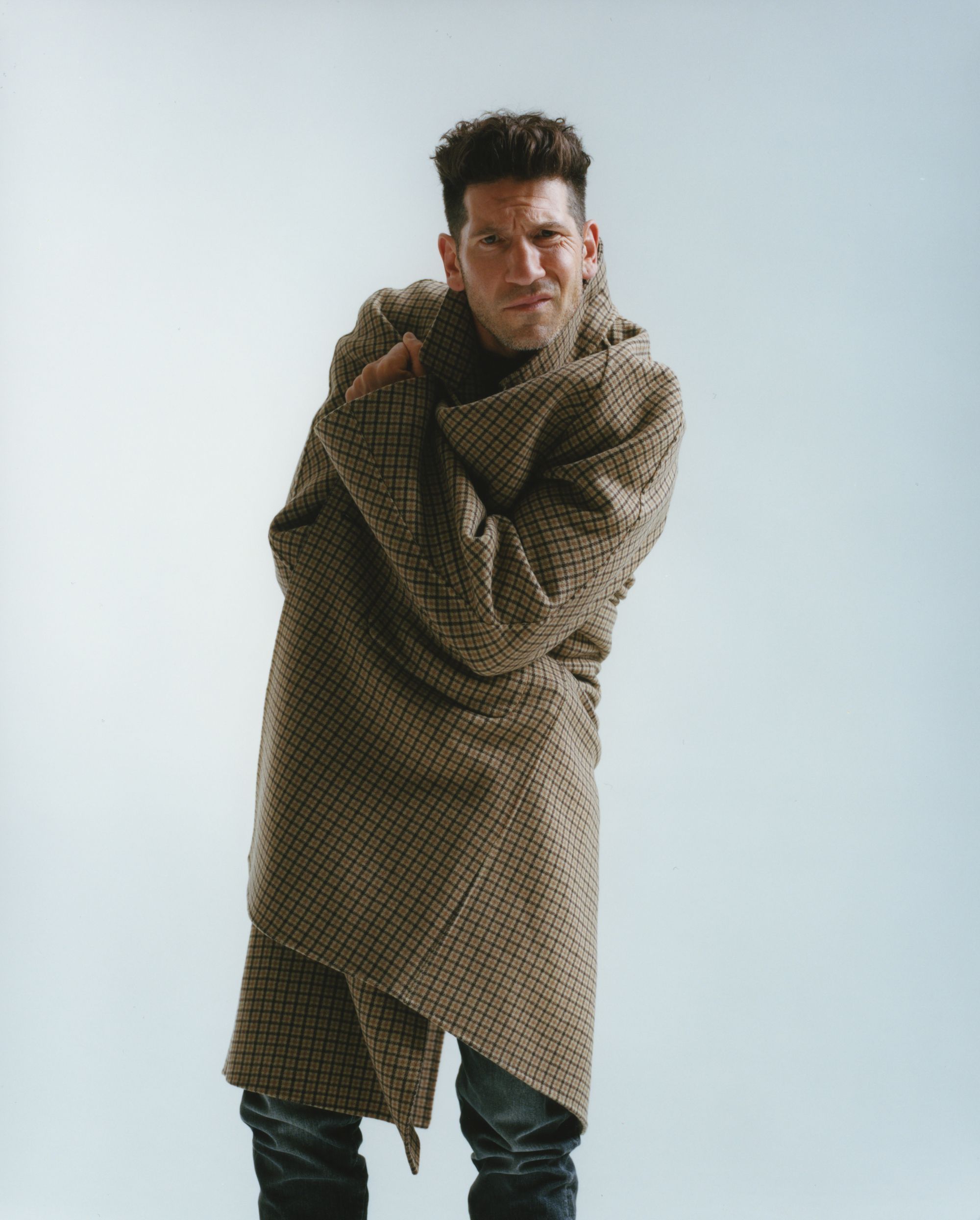

Coat by Michael Kors Collection, T-shirt by The Gap, Jeans by Armani Exchange.

Here’s a rundown of all the projects Jon Bernthal has on the horizon, in chronological order: Small Engine Repair, The Premise, The Many Saints of Newark, King Richard, Sharp Stick, American Gigolo, and We Own This City. In other words, he’s busy. But he’s also versatile. Sprinkled in there is a Sopranos prequel, a sports biopic, a Lena Dunham dramedy, a prestige-TV remake of an American classic, and David Simon’s first Baltimore-set show sinceThe Wire. And there’s a good chance that in each one of those projects, the 44-year-old actor will be the most persuasive thing you see onscreen, thanks to a slavish devotion to his craft that has Lena Dunham wondering how—and why—he does it.

———

LENA DUNHAM: How are you, baby?

JON BERNTHAL: It’s good to see you.

DUNHAM: You look amazing, J.B. Where do we find you today?

BERNTHAL: I’m in Baltimore. We’re getting ready to shoot. I think this one’s going to be special.

DUNHAM: I was joking that you’re my only friend to ever call me and say, “I was out on police raids all night.” Every time I see you, your appearance is slightly transformed. You’re always rocking a new haircut, possibly a new body build. Even though your soul remains unchanged, you’re disappearing into roles, and I think that’s chalked up to the intensity of your relationship to research. When we did our movie [Sharp Stick], which is a domestic comedy-drama, you were like, “Is it possible for me to live in the house that we’re going to be in for a week?” How would you talk about your relationship to researching roles?

BERNTHAL: My motivation is often fear-based. I feel extraordinarily lucky to be doing this, and I really don’t want to fuck up. I’ve always been jealous of those actors that can just show up. But the thing that I’ve found to be the biggest gift is the people I’ve gotten to meet along the way, and the people who have opened up to me and invited me into their worlds and shared their stories. It’s sacred. It’s unbelievable how that informs the work. When we worked together, it was your story and it was coming from your heart, and I could really trust that. So the research was opening up my heart and being with you. When it’s two people working together as artists, it’s always going to be stronger than what you’re bringing in on your own. But you never know if you’re going to get that, so I dive in pretty full-on.

DUNHAM: One of the amazing things I’ve learned from being in your world is that you’ve formed intense relationships with people moving through the prison industrial complex, intense relationships with police officers, intense relationships with gang members. It’s given you a full-throated view of the very divisive and complicated world we live in, and that’s allowed you to have an empathic approach to the characters you play. In our film, you play a character who people will have different attitudes about—whether he’s a bad guy doing good things, or a good guy doing bad things—but you manage to do it with empathy. I’m curious about what your approach is like.

BERNTHAL: Empathy has been systematically stripped out of what we think is masculine. The strongest person I’ve ever known is my mom. She took in foster kids from all walks of life. I saw her treat each one with an unbelievably open heart. I think there’s a fundamental obligation as a storyteller to empathize with the characters that you bring out. So many of the arguments and conversations we’re having these days are people on polar opposites hanging on with such rigidity. Patriotism is being confused with being unbending and fundamental, but there’s nothing less patriotic than being completely steadfast in your views. This country, which I really love, is built on people with opposing views being strong enough to present those views. We can be strong enough to have our views and to talk to somebody who thinks differently than us. I don’t think it’s just about acting or storytelling. It’s also about the kind of person you want to be.

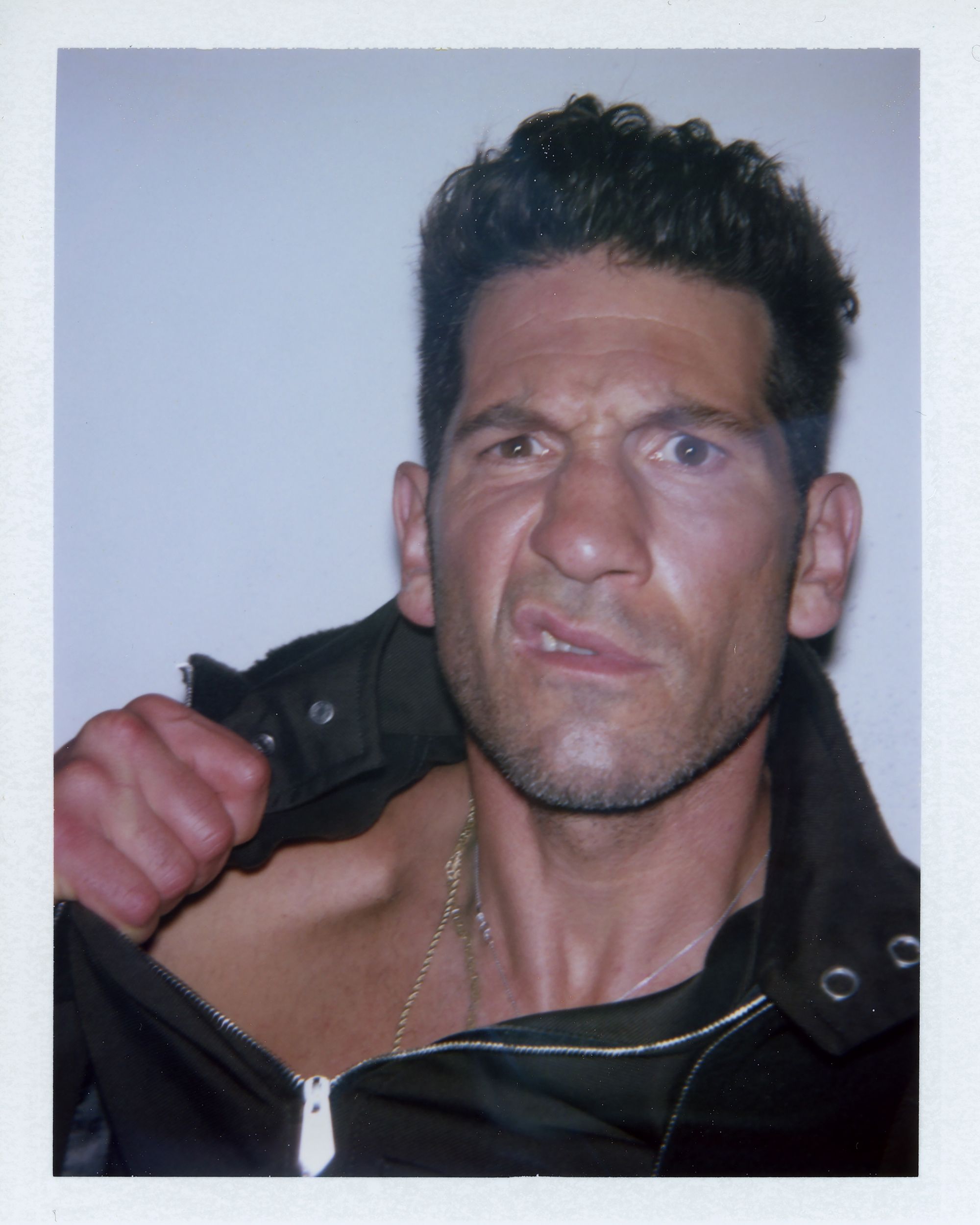

Jacket and Vest by Hermès, Jeans by Armani Exchange, Necklaces Jon’s Own.

DUNHAM: You’ve played a lot of roles that have had an outward, intense masculinity, whether it was a drug dealer, or a soldier, or Shane on The Walking Dead. But you always manage to find this soft, compelling, complicated, weird core. When I finally watched The Punisher, it was fascinating, because this idea of masculinity is actually the chocolate coating on this much more complicated gooey center that’s a conversation about trauma disguised as a superhero. One of the reasons I connected to your work was because I was obsessed with you as a character actor. There’s no logical reason that a nerdy girl from New York should be obsessed with the work of a character actor. And now, we have the funniest, most illogical friendship. You could bench press my entire family, but secretly, you’re so emotional.

BERNTHAL: When we met and hung out that night in London, for me it was like going to meet Elvis. I was such an enormous fan. When I first watched Girls, I saw a willingness to go to these scary, vulnerable, dark, ugly places. I was like, “Who is this person?” I felt such a kinship with you.

DUNHAM: I’ve had the gift of getting to read a first draft of The Bottoms, which is mind-blowing. You didn’t go into that, like, “Yes, I wrote a script and I’m selling it to Hollywood.” It was years and years of you establishing relationships and thinking about the best and most ethical way to do it. I want to know more about that project, especially because it feels like it was a huge part of your voice as a writer starting to take shape.

BERNTHAL: The Bottoms is my heart. I heard about this story ten years ago while I was researching a movie. I was doing a bunch of ride-alongs with the Shreveport undercover narcotics task force, and they told me this unbelievably wild and tragic story. I started asking people about the same story that the police told me. They told it from a completely different point of view, and I was so fascinated by it. The more people I met in Shreveport, the more the story served as a bridge to getting to know them, their point of view about this neighborhood and its destruction, and the systemic and institutionalized racism that took place to destroy it—the fatality of the war on drugs and the senseless victims on both sides of that war. This story had all that, and I started digging in with no real aim in sight. The guys that the story was about were all doing life in prison, and they were starting to get out after 17 to 25 years inside. I started getting to know these guys well, and also became close with the law enforcement community down there. There was no real ambition to make something. It’s been ten years now, and I’ve been in their prison cells, their homes, their churches, their kitchens, their streets. I’ve been with them through marriages and death. It’s an unbelievably beautiful community down there, and I felt this real yearning for these folks to have their story told. Every writer that I brought down to Shreveport didn’t want to get out of the car and engage, so I wrote it with the folks down there. We all just did it together. Sometimes I feel like I’m pushing the most massive boulder up a hill, but I will never stop pushing it.

DUNHAM: I’m so glad you’re pushing that boulder. I was reading your bio, and it sounded like this Renaissance-man joke. It was like, “Jon Bernthal is also a professional baseball player, a boxer training six days a week, and when he’s not training he’s rehabbing pit bulls, at which point he’s flying kites.”I was like, “Okay, fuck off. I’m in bed all the time. I get it.” What’s so funny is often we have this conception of actors who disappear into parts because they hate their lives and they’re tortured and they want to disappear because they can’t figure it out.But you love your life, you love your kids, you love your fucking family. Every time I text you, it’s like, “My kids and I are on a hike.” I wonder if you feel that stereotype of the method actor who’s drawing from a place of daily torture and it’s not who you are.

BERNTHAL: You’re right. I love my life. I’m absolutely in love with my family and my wife is my best friend in the world. My kids make me want to be the absolute best that I can. All I want to do is be with them and be by their side.

DUNHAM: A lot of people in Hollywood who love their children don’t want to be with them and don’t want to be by their side.

BERNTHAL: Being away from my kids is such a pain, but if I am going to be away from them, I’m going to put every single thing I have into this work. I want them to understand what hard work means, and that when you say you’re going to do something, you have to do it. So when I’m working, I’m all the fucking way in. I’m not looking for respites from the storm. I want to dive into that motherfucker. And then when I can be with my kids, I’m not thinking about the next thing.

DUNHAM: I once got a picture from you, and you had let your daughter give you green toenails, and I was like, “Oh my god, he is smitten, because he has a full manicure and pedicure happening.” You guys are deeply in it together.

BERNTHAL: I’m super close with my mom and dad. One of the reasons I’ve connected with so many folks who have made big mistakes and have been incarcerated or have done things that they regret is, growing up, I made a lot of mistakes. I got in a lot of trouble, and my parents instilled in me unconditional, undying, unchanging, unbending love. I understand the power of that. I understand that we’re all craving that. My relationship with my children is so much bigger than anything else. It’s our responsibility to provide that kind of love.

DUNHAM: That’s one of the reasonsI love Small Engine Repair so much. It’s a movie about fatherhood, which gets me every fucking time because I have such an intense and emotional relationship with my dad. It’s a movie that you produced about the protective relationship between men and daughters, without having that patronizing Liam Neeson I’m-taking-back-my-daughter energy.

BERNTHAL: That play came into my life at a time when I needed it. It was July 3, 2009, the last time I had gotten into really big trouble, and I was working hard to change my life. It was right at the beginning of The Walking Dead, and I met John Pollono. I found this guy who can write this piece that’s unbelievably raunchy, irreverent, and hyper-masculine on the surface, but underneath, I saw that it was feminist. It’s about the ills of toxic masculinity, how locked in people are to that, and how much it’s all a front and a cover and a sham. Doing that play in Los Angeles, at the time that we did it, was really interesting. We performed in this teeny little theater, and I was bringing in cops, fighters, guys that I knew in my life. And then there were all these theater folks coming. It was an unbelievable collection of people and it made for these extraordinary nights at the theater, because it was people who would never go to the theater, and die-hard theater fans connecting over this piece. It’s a real testament of John’s work, and I’m excited for the movie to come out.

DUNHAM: Even though I haven’t seen The Many Saints of Newark, these things you’re talking about could be discussed as a big part of the legacy of The Sopranos. There’s so much I didn’t understand the first time I watched it, about the intelligence of the way that it’s taking down so many tropes of the tough-guy narrative. I watched it with my parents when I was 11, like, “I don’t care about gangsters,” and when I watched it as an adult, I realized the very idea of sending a gangster to a therapist is groundbreaking because it’s breaking down how men can communicate, and what violence is and what it does to you. I’m so curious about what it was like to enter this already-established world with David Chase. You’re doing the equivalent of a superhero origin story, only in this other universe that’s so important to the ways we tell stories now. It’s the dawn of modern television, basically.

BERNTHAL: It’s so unbelievably humbling, and shoes that are impossible to fill. When I started my career somebody told me that I had to have goals. I was like, “My goal is to be an extra on The Sopranos.” David Chase is not just a genius, he’s next level. When he was writing The Sopranos, he knew intricate details of every character’s history. It’s nothing less than Shakespearean. The things that are in this movie you can see play out in the series, and it’s so clear that the well he has as an artist is just endless and staggering. And then being able to do this with Michael Gandolfini meant so much. Growing up with his dad being Tony Soprano, and then losing his dad when he did, he was on a beautiful journey of trying to understand his father. He approached it in such a beautiful, mature, and courageous way. It was very clear that my job in this movie was to be there with Mike, by his side, and have his back.

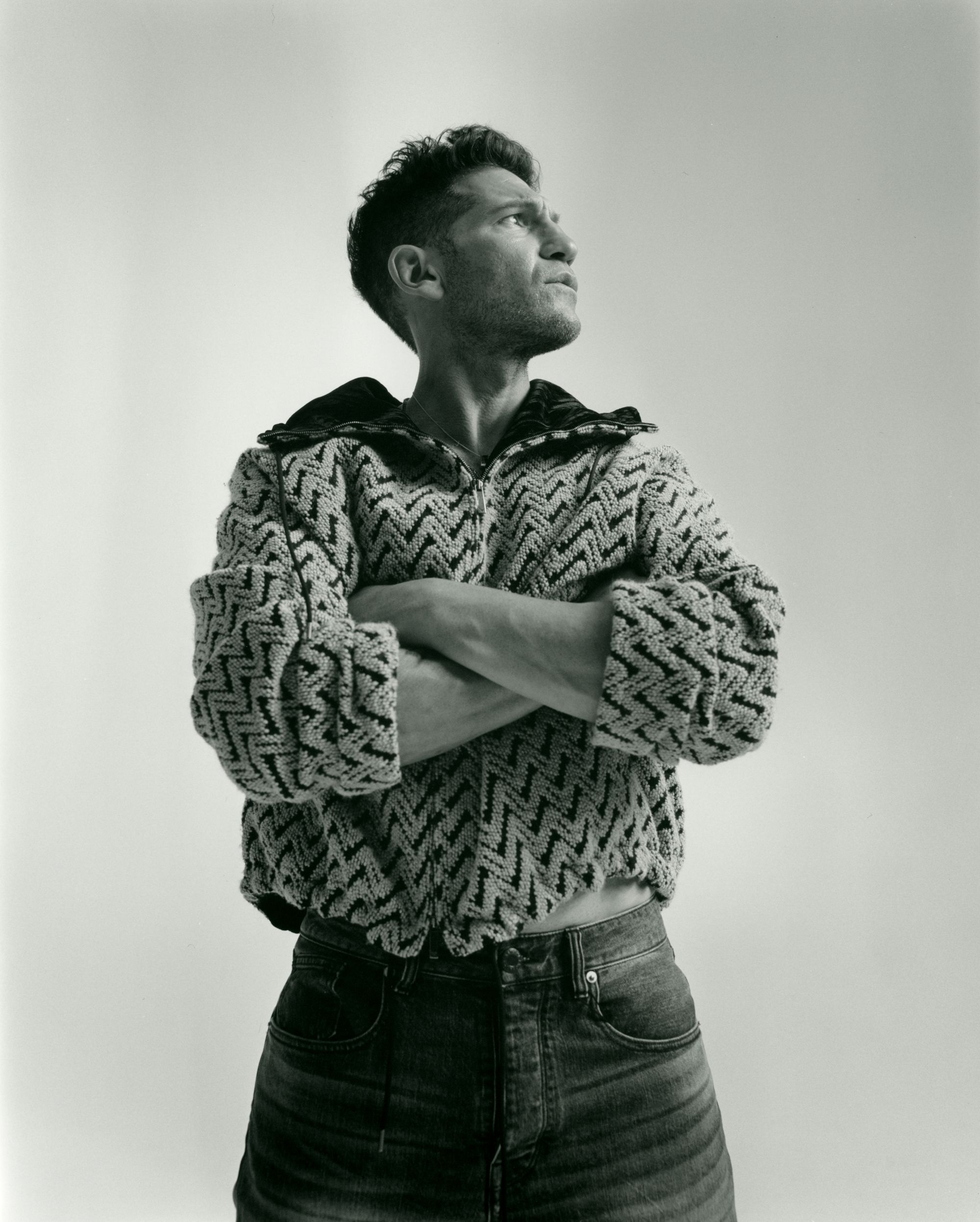

Sweater by Emporio Armani, Jeans by Armani Exchange.

DUNHAM: It’s very you to answer a question about yourself and have the takeaway be about another person. You’re always thinking that way, and thinking about your scene partner. After we worked together, I was talking to my dad about how I realized you fall the best, and look better than anyone else doing an action, because you’re the only person I’ve ever worked with who doesn’t have vanity, and so, by having no vanity when you’re working, you manage to ultimately look cooler than everybody else.

BERNTHAL: I’m saddled with this giant, broke fucking nose and these huge ears. You are what you are. But you have this heart that you lead by. A director is so frickin’ important because a director can really create an atmosphere. You and Scorsese are the best ones, because you create an environment that is all heart. Anybody would be making such a big mistake to give a fuck about concentrating on what they look like in one of your pieces, because you’re giving them the opportunity to let their heart go.

DUNHAM: There’s this scene in the movie where I have a double chin, and my hair is all over my face, snot is coming out your nose, everyone’s hair is flying, and I’m like, “This is why I got into making movies, fort his ‘Robert Altman–Shelley Duvall having a baby on the floor’–level insanity.” And after every single take, you came back like, “Do you want me to go even further?” And I’m like,“Yes, I do!” I look forward to so many more years of writing and making things with you, but I’m going to let you go because you probably have a ride-along to the moon tonight.

BERNTHAL: [Laughs] Costume fitting.

———

Grooming: Kumi Craig using Dr. Loretto at The Wall Group

Photography Assistant: Chad Hilliard

Fashion Assistant: Meg Yates