Huston!

The Films of John Huston

As a writer:

The Murder In The Rue Morgue, 1932

The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse, 1938

Jezebel, 1939

High Sierra, 1941

Sergeant York, 1941

Three Strangers, 1945

As an actor:

The Treasure Of The Sierra Madre, 1947

The List Of Adrian Messenger, 1963

The Cardinal, 1963

The Bible, 1966

Myra Breckinridge, 1970

As a director:

The Maltese Falcon, 1941

In This Our Life, 1942

Across The Pacific, 1943

Let There Be Light, 1945

The Treasure Of The Sierra Madre, 1947

Key Largo, 1948

We Were Strangers, 1949

The Asphalt Jungle, 1950

The Red Badge Of Courage, 1951

The African Queen, 1951

Moulin Rouge, 1953

Beat The Devil, 1954

Moby Dick, 1956

Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, 1957

The Barbarian And The Geisha, 1958

Roots of Heaven, 1958

The Unforgiven, 1959

The Misfits, 1960

Freud, 1963

The List Of Adrian Messenger, 1963

Night Of The Iguana, 1964

The Bible, 1967

Casino Royale (part), 1967

Reflections In A Golden Eye, 1967

Sinful Davey, 1969

A Walk With Love And Death, 1969

The Kremlin Letter, 1970

Fat City, 1971

The Life And Times Of Judge Roy Bean, 1971

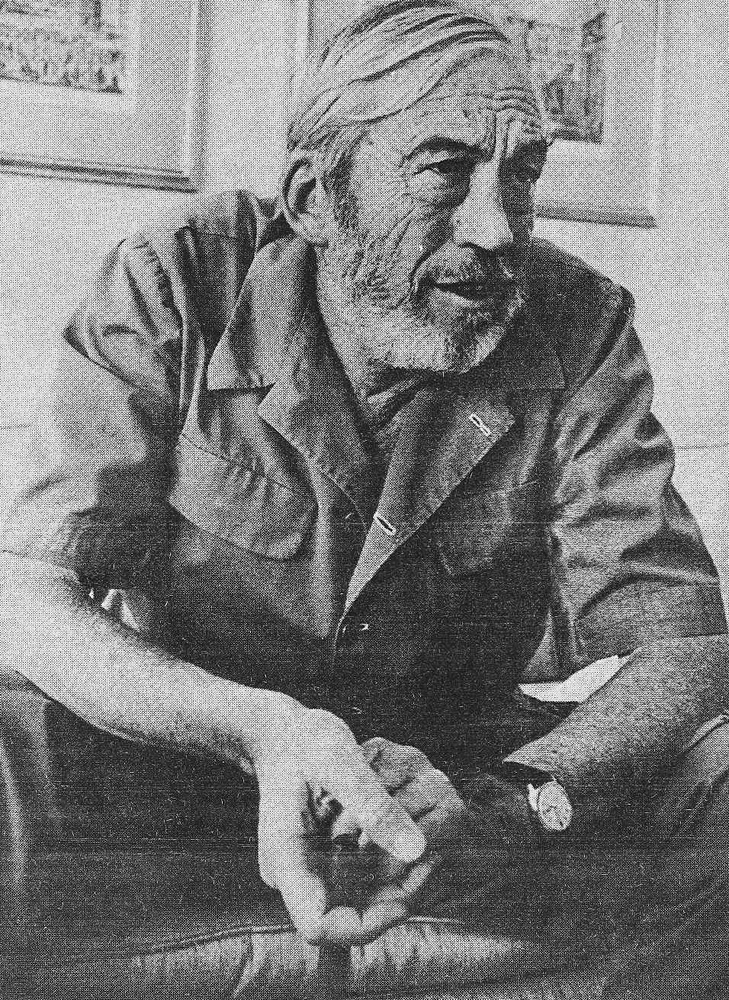

We spoke with Mr. Huston in his suite at the Regency Hotel shortly after the opening of Fat City in New York. Mr. Huston greeted us graciously in his deep round tones and made us quite comfortable in his warm patrician manner. He was in fact quite comfortable and relaxed himself. Several of his beautiful grown children walked through the suite occasionally as Mr. Huston, clad in a mint green safari suit which bared his sunburned belly when he reached for a cigar or a glass of white wine, answered our questions patiently and with delightful wit in word and inflection. As we entered he was bidding friends goodbye with kisses and sentiments that displayed years of mutual affection. When we left he made us friends, he called after us in the hall, “Goodbye boys!” and then as grand after thought, “Goodbye darlings!” words which carried the ring of an Olympian blessing gone Hollywood.

GLENN O’BRIEN: Did you like making Fat City more than a picture like Kremlin Letter?

JOHN HUSTON: I’ve been a boxer and I’ve never actually served as a spy, so lets say I’m a little closer to the material. It’s a very personal story.

OBRIEN: When Fat City showed at the Museum of Modern Art the other night you introduced Stacy Keach and said you’d introduce Susan Tyrell after the film since no one had ever heard of her. Then you didn’t.

HUSTON: Well the film was over and she was on her way out, but I’m sure everybody saw her didn’t they?

O’BRIEN: She was so great. How did you find her?

HUSTON: I saw a test that she had done with Stacy Keach for another part. She didn’t get the part, but I saw this test and there was no doubt from that moment that she was the girl for it. She wasn’t the same girl in the test that she was in the picture, but all the qualities were there.

O’BRIEN: Was it her first film?

HUSTON: Yes I think so. I think she’s worked at Lincoln Center and done some off Broadway things.

O’BRIEN: She’s extraordinary.

HUSTON: She is extraordinary isn’t she? A flower maiden if there ever was one.

O’BRIEN: The scenes between Stacy and Susan went so well. Were they long, long takes?

HUSTON: Yes.

O’BRIEN: Did you do many?

HUSTON: No. They’d been rehearsed. They’d rehearsed with each other privately, and in my presence and they were just wonderful. There was scarcely anything at all for me to do.

O’BRIEN: Did they improvise at all?

HUSTON: No. One tries to look that spontaneous of course.

O’BRIEN: The look of the film was so realistic, for example in the bar. Was it all available lighting?

HUSTON: Yes it was with just a few little lights in a bar. Conrad Hall is extraordinary at this. Stockton, California has a particular thing that happens there. It probably does in other cities in the United States too. The outside is kind of dazzling with blinding light. So when you go into a bar it’s like the way you sometimes stumble into a theater and can’t find your way until your eyes adjust themselves. There you reach around and try and find a barstool the same way you try and find a seat in a theater. This is what led Connie and I to do the outsides with explosive skies and background and the interiors, which were all on the spot, almost in silhouettes.

O’BRIEN: The character actors were all so fantastic. Were they professionals?

HUSTON: Oh no. Really only Stacy Keach and Susan Tyrell and I suppose you’d call Nick Kolisantes a professional. He’s the fight manager and he’s a television director. And Jeff Bridges. This was really his first big part. It was before The Last Picture Show. Except for them, the others were mostly boxing chums of mine and people we discovered in Stockton. The black boy who does the talk in the dressing room is in high school in Stockton.

O’BRIEN: Did you tell him to pretend he was Cassius Clay?

HUSTON: No but the other afternoon Cassius Clay saw the picture in Dublin before the fight and he talked back to the screen. He said, “He’s usin’ my talk! That’s me talking.”

O’BRIEN: How did the picture go over with boxing people?

HUSTON: They loved it. The blacks particularly.

O’BRIEN: I’ve never seen blacks presented better in a movie. Susan’s boyfriend was great.

HUSTON: Curtis Cokes. He’s an ex-welterweight champion. Never done a bit of acting in his life.

O’BRIEN: This is your second movie in the United States in twenty years…

HUSTON: Since The Misfits.

O’BRIEN: You live a very cosmopolitan life all over the place and then come back to the States and make very beautiful and simple statements about a place you haven’t been in twenty years.

HUSTON: Maybe I have a little perspective on it.

O’BRIEN: The scene with the wine and the roses was so wonderful.

HUSTON: That actor was a man who was on relief in Stockton. An ex-boxer named Dixon.

O’BRIEN: You’ve made another film since haven’t you? With Ava Gardner.

HUSTON: Yes she’s in it. It’s a wild one. It’s called The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean and it’s with Paul Newman. Stacy Keach is in it, a wonderful brief sequence where he plays an albino gunman.

O’BRIEN: You’ve been pretty hard to nail down by the auteurists. You’ve been all over the lot, not consistent in theme like Howard Hawks who makes wonderful films, but very similar ones.

HUSTON: I jump around a lot that’s all. They seem to have a continuity of interest. I scarcely make two pictures alike.

O’BRIEN: Do you think a theme has evolved?

HUSTON: I can’t judge that. It’s quite beyond me. I’ll do what’s of interest at the time and hope it will be of interest to the people. I’m not out to make any given statement. I haven’t made up my own mind about anything. That is finally and conclusively. When I do I’ll probably shoot myself.

O’BRIEN: Was your Jim Beam ad with Dennis Hopper any kind of statement?

HUSTON: No. It was amusing I thought. The same way I made certain films I thought were amusing.

O’BRIEN: What’s Judge Roy Bean like?

HUSTON: It’s a western but I’ve never seen a western like it. It’s outrageous. It doesn’t go along with any set of rules or have any particular form. It violates all the conventions and I hope it’s as amusing to see as it was to make. It doesn’t take itself too seriously. There are sentimental moments but scarcely ever solemn and never pompous.

O’BRIEN: Quite a few of your films like Beat the Devil, Moulin Rouge maybe, and The Misfits have become cult favorites even though they were not loved at the time.

HUSTON: Reflections in a Golden Eye is coming into that category. People are talking about it more and more. It’s just as bad of course to be before your times as it is to be after your time.

O’BRIEN: What films of yours do you think have been overlooked?

HUSTON: Freud was a little damaged in the editing but I think once you get into it it’s a good film, even profound film. And I’m delighted that Reflections is taking its place now among my better films.

O’BRIEN: They’ve stopped the color effects now.

HUSTON: It’s a great shame. It was never intended to be shown in straight color. It’s like shooting a picture in black and white and having them make a color film out of it. It’s not right to show it in straight technicolor, but the man responsible for this I believe stopped developing sometime earlier in the century when he saw a beer ad. He was duly impressed.

O’BRIEN: Did you see McCabe & Mrs. Miller?

HUSTON: Yes. I think it’s a wonderful picture. I think it’s one of the best American pictures. A marvelous film.

O’BRIEN: The color effects in that are just incredible.

HUSTON: The whole picture in my opinion is just incredible. It’s a classic.

O’BRIEN: Did you see Altman’s other films.

HUSTON: I didn’t see M*A*S*H*. I saw the other one Brewster McCloud. Very interesting, delightful. But not to be compared with McCabe & Mrs. Miller which was so fully satisfying to me in so many ways. It all came together. Beautiful performances, great idea, technically beautifully executed, exquisite taste … Hats off to Altman.

O’BRIEN: Are there any other recent films to come out of this country that you liked?

HUSTON: I liked the film that nobody’s been allowed to see apparently. The studio that made it seems to be ashamed of it. The Traveling Executioner, with Stacy Keach. A marvelous film with unforgettable scenes. Apparently they opened it in a few places and it got middling to bad reviews. Nobody knows how good it is that’s all.

O’BRIEN: I didn’t know they did that anymore. That sounds like the old Hollywood.

HUSTON: No! They do it more now than they ever did. Much more. Before a major studio had theaters it had to supply so every picture had shot, at least a few days. For instance The Asphalt Jungle had no stars in it and by the time it came off it was getting bigger play than when it opened, but it had to come off because they had another picture coming in.

O’BRIEN: Sinful Davey lasted about a week.

HUSTON: I can’t imagine how that one lasted three days. After the fuck up That Walter Mirisch made of it.

O’BRIEN: Is that another re-edit job?

HUSTON: Yes.

O’BRIEN: Why does that happen to you so often?

HUSTON: It’s only happened really twice. Sinful Davey and The Barbarian and the Geisha. I know The Red Badge of Courage is talked about but that’s quite forgivable really. Today very often the studio, if you can call them that, will calibrate and measure and come to a mathematical conclusion that it will cost more money to release a picture than they could possibly make, so a picture like The Traveling Executioner, if they haven’t got very good evidence that it’s going to make money right off the bat they don’t release it. And the number of pictures that have not been released is quite amazing. And as far as cutting goes, no one as far as I know, at least I’ve been assured of this, has final artistic control of a film.

O’BRIEN: What do you think of Ken Russell?

HUSTON: I liked Women In Love enormously. I thought it was an absolutely beautiful picture. I didn’t see The Music Lovers of the Devils.

O’BRIEN: What are you going to do now?

HUSTON: I haven’t decided. I’m going to go back to Ireland and get on horse and cool out. I’ll decide but I don’t care how long it takes me.

O’BRIEN: I’ve heard that Bertolucci may remake The Maltese Falcon.

HUSTON: I don’t think a remake. It’s going to be the son of Sam Spade I think. The owner of the property asked me if I’d care to do it and I said certainly not.

O’BRIEN: Bertolucci is doing Red Harvest next.

HUSTON: He’s doing Red Harvest?

O’BRIEN: Yes. Did you see The Conformist?

HUSTON: No. I hear it’s terribly good.

O’BRIEN: That’s another picture that almost wasn’t released. And McCabe & Mrs. Miller was released very badly too and wasn’t much of a success.

HUSTON: I would have thought it would have been embraced.

O’BRIEN: Did you see Images at Cannes?

HUSTON: Yes. I liked it. I was fascinated by it.

O’BRIEN: Leonore Fini designed costumes for you. What is she like?

HUSTON: An extraordinary woman. I think she fancies herself a cat. She’s certainly the most popular woman painter in Europe, enormously talented, and she commands very high prices. She’s a delightful woman, lives in a wonderful atmosphere. She’s probably the best known theatrical costume designer in Europe. Numero uno. An enchanting, fascinating female. I guess she’s in her fifties now. Men cluster around her. I should think even a few women.

O’BRIEN: I’ve been reading Madame, Patrick O’Higgins biography of Helena Rubenstein, and he describes a party he attends with Madame R. and Audrey Hepburn is there, and Genet and Alice B. Toklas. And he notices Madame Boussquet extricating herself from under a pair of legs that prove to be John Huston’s.

HUSTON: Ha ha! She was wonderful, Madame Boussquet. She was the social arbiter of French social-artistic life. Well that was an error!

O’BRIEN: Did you know Helena Rubenstein?

HUSTON: Oh yes. She had great taste of course. She brought together a great collection. She had a wonderful eye.

O’BRIEN: Did you devise a special technique for working with Zsa Zsa?

HUSTON: A little complicated that was. I love Zsa Zsa. She was taught, and she was a very apt pupil. She learned every motion for that picture. I think she was rather more self-conscious in those days too. We had someone showing her how to move and Marcel Vertege designed the clothes and Schiaparelli executed them and Muriel Smith’s voice was in her mouth. She came off don’t you think?

O’BRIEN: Oh yes.

HUSTON: I think so.

O’BRIEN: When you had decided to make Fat City did you see Stacy Keach in the role immediately?

HUSTON: I hadn’t met him. My first idea was Brando and Brando was undecided about playing it and time was wasting. I saw Stacy Keach in The Traveling Executioner and there obviously was a wonderful talent that could lend itself to Fat City. I met Stacy and in the meantime we were waiting to hear from Brando and didn’t so we closed on Stacy.

O’BRIEN: Did you have anybody in mind for Oma?

HUSTON: Nobody. I saw the test of Susan for the part she didn’t get and that was it.

O’BRIEN: It seems that with the shrinking of Hollywood that the star system has broken down.

HUSTON: It’s a different proposition today. Before stars would be identified with a certain kind of role, and they played that in perpetuity. This is something that a major company could do where the gypsies of today can’t. They would design a whole program of pictures for a star.

O’BRIEN: Do you think the small immediate success of The Misfits was because of Gable and Monroe not living up to their usual image?

HUSTON: That might have had some bearing on it. Of course The Misfits was such an expensive picture, so wildly expensive above the line that it was disproportionate. It cost several million above the line. It made its money back and showed a profit, and for it to do that was quite remarkable. Now it wasn’t a wildly successful picture in terms of the investment. It wasn’t a financial success but it paid everybody off.

CURTICE TAYLOR: I just felt it was a case of the star system backfiring.

HUSTON: Ha.

TAYLOR: I had to see the movie a hundred times before I could say that’s not Monroe, that’s not Gable and see them detached, as characters.

O’BRIEN: I wouldn’t want to detach Monroe or Gable from the characters. It seems to me that The Misfits is such a mythical movie that it is perfectly cast, It’s really the perfection of the star system.

HUSTON: Were you exposed to the old Gable movies?

O’BRIEN: Sure, on television.

HUSTON: He was a figure and an image. He only played a certain kind of role. I think there was a degree of resentment when Charlie Chaplin stopped being the tramp. To see William S. Hart play Hamlet would have gone against the grain. In a sense The Misfits did violate those symbols.

O’BRIEN: What did Clark Gable think of it?

HUSTON: He loved it. He thought it was the best thing he’d ever done. It might have been. I think he was quite extraordinary. Sometimes people say The African Queen wasn’t a real Bogart role. It wasn’t.

O’BRIEN: He lived through it.

HUSTON: And got him an Academy Award as a matter of fact. But it’s not the prototype of the Bogart that is a cult figure now.

O’BRIEN: Everybody talks about new waves. Do you think films have changed radically.

HUSTON: Well we went through a telescope lens phase where flowers and blades of grass where out of focus in the foreground, and some of that was very beautiful until it became a cliché. Now you hesitate to do this. The Japanese were very good at this when it first came out. And the Swedes too. Some very exciting stuff. Styles of photography change, just as in writing. Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar have been doing that for years, even before the Japanese. You can see it in Man Ray and Stieglitz, they were the forerunners. Then for a time there was the long focus lens. Orson used it in Citizen Kane. Wyler used it. I used it. The figures in the background are as clear as those in the foreground. I don’t see why one shouldn’t resort to these things if it’s in keeping with the idea of the picture.

O’BRIEN: Are you going to act anymore?

HUSTON: Oh I don’t know. I’m invited to occasionally. I’m duly flattered but I don’t take myself seriously as an actor for two minutes.

O’BRIEN: You scared the hell out of me in the De Sade thing.

HUSTON: I’ve never seen it.

O’BRIEN: You were terrifically perverse.

HUSTON: Why thank you.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 1972 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more from our archives, click here.