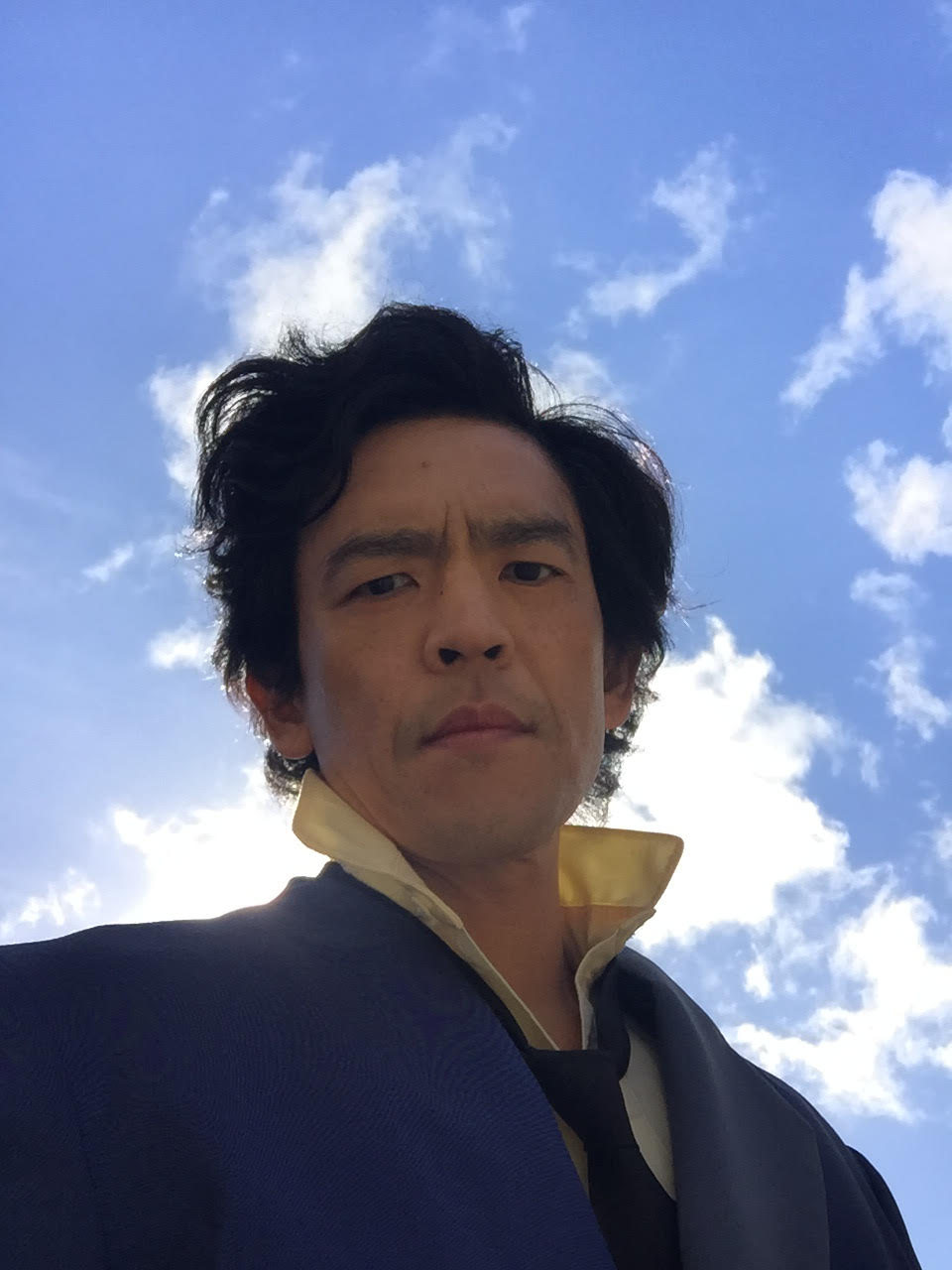

John Cho Is Right Where He Belongs

John Cho may have gotten famous thanks to the Harold & Kumar movies, and he may have become ubiquitous thanks to the Star Trek movies, but it was Columbus, a tender film about the complicated dynamics of a father-son relationship, that signaled his blossoming as an actor. Since that 2017 indie, Cho has undergone career course-correction into leading man territory, starring in projects like Searching, a widely-acclaimed virtual thriller, and now, as the intergalactic bounty hunter Spike Spiegel in Cowboy Bebop, Netflix’s live-action adaptation of the influential sci-fi anime. To mark the launch of the series, Cho reconnected with his Columbus director Kogonada to discuss escaping your past, accepting your mistakes, and finding your place in an indifferent world.

———

CHO: Kogonada, how are you, man?

KOGONADA: Good. How are you doing?

CHO: I’m good. Oh, the lengths I will go to get you on the phone. I’m so glad you agreed to this. How cool is it that the two of us are in Interview Magazine? This is a moment for me.

KOGONADA: I was so honored that you asked me. I’ve always been reluctant to—

CHO: Do things like this. I know.

KOGONADA: Yeah. When it came from you, I thought, “Oh, I have to.” It’s always nice to connect with you. I always feel very stimulated and enjoy talking with you.

CHO: One of the reasons you were the first name on the list for me was, while I was making Cowboy Bebop, I thought of you frequently, because the show is clearly made by cinephiles, and because it plays with genre.

KOGONADA: That’s interesting. I thought you were going to say that I was top of your list because Cowboy Bebop is filled with lonely, alienated people.

CHO: That too. Ennui, ennui.

KOGONADA: I remembered this morning about a time we met in Koreatown, and you took me to a secret bar which we entered through a vending machine in a hallway. That was a very Cowboy Bebop moment for me. Do you remember that?

CHO: Yes, I do. That was a good mistake on my part. That was the loudest bar in the world. I was like, “I can’t hear him. This is awful. What have I done?”

KOGONADA: It was otherworldly for me. You were like, “Hey, let’s just go around this corner.” Suddenly, we were in some industrial hallway. I was like, “Are you going to kill me right now?”

CHO: I was showing off.

KOGONADA: I remember when I was walking behind you, watching this incredible wave of reaction. There was just so much joy and appreciation when people saw you. Like you were one of their own, and you seemed so beloved. Now, here’s my feeble attempt at a segue, but Cowboy Bebop is filled with lonesome beings who don’t belong. Do you feel like you belong anywhere?

CHO: Sometimes intensely yes, and other times intensely no, in the sense that my identity—the adjectives typically used to identify a person, like “Korean” or “American”—are becoming less and less relevant. I do feel like my core values are becoming more clearly defined to me. I feel clearer about my purpose, and who I love. I feel like I am where I’m supposed to be. Looking back on my childhood, and immigrating to Houston when I was six, we moved around a lot, and it all seemed traumatic. Sometimes I think moving—being displaced—is the central trauma of my life. That’s what I’m addressing in my career, going onto new sets, and forcing myself to be the new kid in school. I’m recreating a trauma that I can control, over and over again. When we moved to New Zealand, I saw my kids adapt so easily. Kiwi kids, they run around barefoot. My daughter walked out of school barefoot. I said, “Do you want to put on your shoes?” She refused and she walked home barefoot. I thought, “That was fast.”

KOGONADA: Wow.

CHO: I guess I built up this sense of dislocation for myself, like it was my trip and not theirs. I had to reassess the whole thing in my head.

KOGONADA: I think the reason Cowboy Bebop has resonated so much is that it captures a lot of great narratives of the 20th century. This feeling of dislocation is a modern crisis. Maybe that is exactly what the crisis of modernity is—we no longer feel part of these tribes and long histories. Part of being modernized is that you feel more alienated or disconnected. I was thinking about Cowboy Bebop as this sort of postmodern cowboy story—the cowboy is always the loner, and Spike Spiegel is the essence of that. It also made me think about a conversation we had where you had told me that you wanted to play a cowboy. Do you remember that?

CHO: I have always wanted to play the cowboy, and I’ve always loved Westerns. There’s a simplicity that I always admired about them, as an actor. Like, “Can I be that confident? Can I be that simple?” There was also the iconography that I always liked. I haven’t talked about this, but more than anyone, I was thinking about [Humphrey] Bogart and Bob Dylan. I wonder if that makes sense to you.

KOGONADA: I mean, Bogart certainly. And Dylan.

CHO: There is a way that Spike moves, like an early ‘20s slouch, the way he puts one hand in his pocket and his elbow sticks out [while] smoking cigarettes. I started wondering, like, “Is this Dylan? Does Spike have Bob Dylan hair?”

KOGONADA: I love that. What did that do for you, to feel like you were sporting Dylan hair?

CHO: Well, if I think of Spike as Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan, to me, is the coolest guy that ever lived. That’s superficial, but it feels like everyone’s been chasing Dylan for years. There is a refusal to comply with any traditional semblance of biography. He’s like, “I’m not going to tell you what you want to know about how I came to be. My origin story is cosmic.” That refusal to use the vocabulary of earthlings, I thought that was a good approach to take.

KOGONADA: That’s original cool. Today that would be almost anti-cool, because cool has become just a brand or idea, but then coolness was resistance. Especially in an age where everyone shares so much of their biography, I love the idea that you embrace this sort of resistant form of it.

CHO: He was really not-compliant in every form. Looking at Don’t Look Back I just thought, “Wow. He didn’t listen to anyone.” I’m here doing press for Cowboy Bebop, TikTok videos and Instagram live. Eventually I was like, “What am I doing here?” Bob Dylan didn’t give a shit.

KOGONADA: Cowboy Bebop is such a mishmash of genre, so layered that maybe you needed layers of inspiration. I love that you reached into music history to flesh out an iconic character who is an anime character. How did you get inside of it?

CHO: Like so many of the characters in that show, there are people who carry loss, as if they’re carrying around an empty box and don’t know quite how to fill that box back up. I guess that’s the postmodern quality. It seems quite romantic to me, just carrying around that emptiness and trying to hide it—that is the only way I could really get my head around being cool. It’s not something you can play. It’s the affect of not caring about anything, when in reality you care so deeply about whatever it is you lost.

KOGONADA: I love that. Maybe that’s why you work from the outside-in, because emptiness is at the core of your being. That is such a strength of yours, the physicality of your movements. There’s so much detail. I remember when I was working with you, I was always mesmerized by these choices that were minute and physical. Did you enjoy that part of it, or was it a burden?

CHO: I enjoyed it as an extension of acting. This is going to sound weird, but there’s a very strong connection for me between the martial arts sequences in Cowboy Bebop and Columbus, which was like my birth as an actor. In how safe you made us feel, the story and the characters that you presented us with, and the generosity and the freedom you gave me to express myself physically in those spaces that you set up.

KOGONADA: That means a lot. There’s something about the way you move through space, the way you touch objects. You’re really good in the quiet, and that isn’t easy. I was thinking of Alain Delon in Le Samourai, which is so quiet. You have that quality. So much of anime is posture, and in Cowboy Bebop, you have these incredible silhouettes. I thought, “God, you are so perfect for this form.”

CHO: Compared to American animation—let’s take Pixar as an example—anime focuses on these tiny movements of the face, like eyebrow raises and the little twitch of a cheek. When it comes to the face, they use templates. In contrast to American animation, the physicality, the body postures, the tableaus and silhouettes is so central in anime. The Japanese depict rain or wind in ways that you would never see in American animation.

KOGONADA: I love that about anime. If you think about Miyazaki, it’s all about modernization and the connection to nature. It’s this attempt to overcome modernity in the world—especially the east—because modernization was sort of imposed. At the time, to be modern was to be Western. This is the genius of Cowboy Bebop, too—it is a version of a Western, but it’s so deeply a part of the future and so deeply a part of another region’s history as well. It has stayed in the zeitgeist for so long. It definitely didn’t just resonate in the east. We’re all longing for something that feels authentic, and not defined by hyper-capitalism or the onslaught of technology. And that doesn’t mean we long to return to some innocent past.

CHO: For my family and many other Korean ones, the West and modernity are also tied up in the victor’s god—Christianity. That’s a lot to accept from another culture: to learn that your system of government is going to change, your ideas of family are going to change, and your idea of god must change, too. That’s a lot of change to absorb in a few decades, and I think in a lot of ways I’m still reeling from all of that. The show is filled with people feeling events that are not depicted, just remembering things. Even Cowboy Bebop is a memory of the future that hasn’t happened yet, because all sci-fi is a snapshot of the time in which it was made.

KOGONADA: Even the design is sort of retro-futuristic. Thematically, Cowboy Bebop is about the impossibility of escaping your past. This is especially true for Spike. He’s trying desperately to move forward. I wonder about your own feelings on that. Is it possible to escape your past?

CHO: I think I do. Sometimes I’m dealing with a past that I inherited from my parents, and sometimes I’m dealing with a past that goes further back than that. That sounds maybe overly poetic, but it’s something I actually feel, and would imagine that a lot of people feel.

KOGONADA: Do you feel burdened by it, or do you think it’s about acceptance? This is a question for your character as well. How did you deal with this character who obviously has a past?

CHO: This isn’t an answer, but it is a reply and pivot. I obsess over mistakes that I’ve made, mostly social mistakes. It’s debilitating, the time I spend thinking about those errors. More and more now, I tell myself, “You’ve got to forgive yourself. You are a human being.” We are just going to fuck up forever. As long as you’re alive, you will be stumbling, and that’s the condition.

KOGONADA: I feel the same way. I’m consumed by the choices I’ve made, and life is a million choices. But there is a general happiness that you bring out in people. You’ve been in the public eye for a good while, and it has always been fairly positive. Do you feel beloved?

CHO: If being beloved is the capital that I’ve accrued over the years, I’m risking it at the poker table with Cowboy Bebop. I’m like, “Okay, we’ll see what happens.”

KOGONADA: Are you feeling the pressure because it’s such an iconic anime and character?

CHO: I would be lying if I said I didn’t. The only thing that I comfort myself with is that I was asked to do it. I did try my best, and I can honestly say that. We’ll see what happens.

KOGONADA: It’s impossible to replicate [anime] exactly, because anime is its own form. Once you put human beings up to embody it, it already becomes something else. Again, you can be haunted by the past, and it’s different if you’re in your twenties than your forties.

CHO: I was reflecting on that too, because I don’t know that I could have done this in my twenties. When I was young, the future was something I was just running toward. Our conception of the future as a culture was so different. Two or three decades ago, the end of the world seemed millions of years away. Now, it seems rather imminent. There is this feeling of looking backwards that’s a really big part of the show, that I’m not sure I could’ve accessed in the proper way when I was younger.

KOGONADA: Hey, if people reject it, put on your Bob Dylan hat, man. You know what I’m saying?

CHO: I’m going on Amazon right now and ordering a big pair of black shades.

KOGONADA: This is your electric guitar era.