Don’t Call John Carpenter A Horror Movie Director, Says John Carpenter

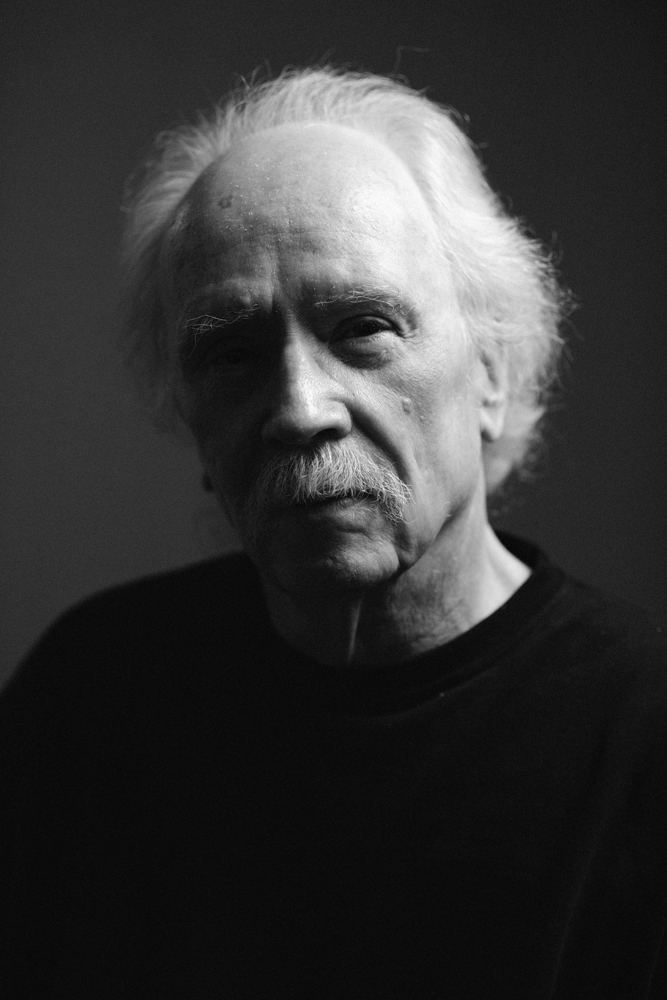

It’s odd that the piano—such a classical and majestic instrument—would bring to mind one of the most potent names in the horror and sci-fi film genres. But back when I was a kid budding into a somewhat decent piano player, there were really only a couple of tunes that would come to me when I had the instrument at my hands: “Home Sweet Home” by Mötley Crüe (of course) and the theme from Halloween by the iconic 1978 film’s director, John Carpenter. The choppy, menacing, and morbidly catchy staccato hook of that song rang in my head for days after I’d seen the movie. It was like Chopin’s “Funeral March” reinvented for the late-’70s and ’80s generation. I was a kid hiding from my parents at night with my friends in basements lit by TVs. Movies like Halloween, The Fog (1980), The Thing (1982), Prince of Darkness (1987), and They Live (1988) would lead us into the unknown night and often into the next morning. Carpenter approached many of his films not simply with a mastery of the visual realm, but with a sense of melody and sonic texture that highlights the suspense, tension, and fantasy he’s best known for. Though he did direct some of the greatest horror movies ever (check out 1995’s In the Mouth of Madness if you haven’t seen it; it’s an underrated classic), Carpenter, whose last film was 2011’s The Ward, claims he’s not a horror movie director. He seems, rightly, to find that category too limiting. His filmography does include nonhorror titles such as Escape From New York (1981) and Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992), and in my mind, he’s more the king of imagination. And the music he makes is a big part of that crown.

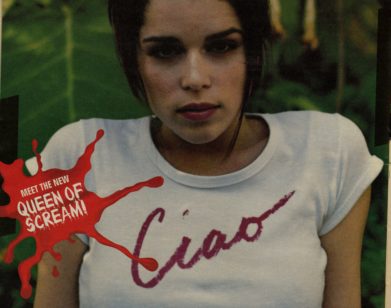

The Halloween III soundtrack was one of the first records I ever owned, and to this day I’m still jamming that original copy. That LP, plus staple Carpenter soundtracks like Assault on Precinct 13 and Dark Star play like synth-wave masterpieces: sometimes synth-punk, sometimes musique concrète, sometimes classical, sometimes almost dancey, but always distinctly John Carpenter. This month the 67-year-old musician is putting out a new LP—his nonsoundtrack solo debut, made largely at his Los Angeles home through hours of improvising sessions with his son and godson. Lost Themes (Sacred Bones) continues the reign of Carpenter’s imaginative kingdom by creating themes for imaginary movies. The instrumental record brings to mind his classic style but meshes it with a more lively rock feeling. Horror fans might hear it and think of the band Zombi and classic Italian prog scores. I was honored to talk to him. -Dave Portner, a.k.a. Avey Tare

———

DAVE PORTNER: I’m a longtime fan of yours—as a musician and as a filmmaker. Let me ask you, how could I turn this interview into a great horror story?

JOHN CARPENTER: Well, somebody’s life would have to be in danger for it to be a horror story. Horror is a reaction; it’s not a genre.

PORTNER: What are your feelings about genres?

CARPENTER: Horror has been a genre since the beginning of cinema, all the way back to the days of silent films. I don’t think it will ever go away because it’s so universal. Humor doesn’t always travel to other countries, but horror does.

PORTNER: Horror goes back further than cinema, all the way back to folktales. Did you have an interest in folktales when you started? Some of your films, like The Fog or The Thing, have a folktale element to them.

CARPENTER: Horror found me, man. I got into the movie business to make westerns.

PORTNER: Really?

CARPENTER: Yeah, but there were no westerns anymore. They’d already died out as a genre, so I made Halloween and everyone came running because it made money. That’s the only reason why.

PORTNER: But I know you’re pretty well versed in the myth of vampires and horror stories, so there must be some attraction.

CARPENTER: I was a big fan of horror movies when I was a kid—and of cinema in general. I didn’t really know literature that well, but that interest came along as I got older.

PORTNER: Like the stories of H.P. Lovecraft?

CARPENTER: Yeah, big time.

PORTNER: His story “The Colour Out of Space” [about a farm perversely affected by a mysterious meteorite that landed there], is amazing.

CARPENTER: It’s awesome. I’d love to make a movie of that in a way that nobody’s imagined it. They did one [Die, Monster, Die!, 1965] back in the Roger Corman days. Daniel Haller directed; it wasn’t so good.

PORTNER: Reading it, I can’t imagine how anyone would go about turning it into a film.

CARPENTER: How do you get a color that no one’s ever seen? I don’t know.

PORTNER: But that’s a question that’s in line with your new record—how do you capture the horror and the unknown? There’s something scary about the unknown. And maybe the scariest movies couldn’t ever be made because they are too deep in somebody’s head, too unknown to get out.

CARPENTER: That’s the idea. This album is for the movies that are going on in your head. Anybody who has grown up in our culture and has seen movies has a movie going on in our head. So the best way to listen to my album is to go into the dark, turn the lights down, put on the album, and start imagining your movie. That’s the movie I want to score.

PORTNER: Did the music come from movies that were playing in your head?

CARPENTER: This whole album came about in an odd way. A few years ago, my son would come over to my house in Hollywood and we’d play video games for a couple of hours, and then we’d go downstairs to my Logic Pro computer program and play and improvise music for a couple of hours. We’d do that back and forth. My son’s a musician, and I am too. Over a period of time, we came up with, I forget how many minutes of music—60 minutes, a pretty big chunk—and then he went to Japan to teach English. I was looking for a new music lawyer, and I found one. She called me one day and said, “Do you have any new music?” I said, “Well, I got this thing sitting around, this improv thing that I do with my son.” I sent it to her and a couple of months later she says, “We have a record label that wants to release it.” That was it.

PORTNER: So what you handed in to her is actually what we’re hearing?

CARPENTER: Yeah! We did do some additional work.

PORTNER: You use a pretty wide roster of sounds.

CARPENTER: I’ve used everything for years and years. Jesus, I can’t even remember. Back to the all-powerful Oberheim that we all bow to, the great sound of the Oberheim. But I have these plug-ins with great sounds. It’s all about the sounds.

PORTNER: How much technical knowledge did you have when you began composing?

CARPENTER: I had no clue about computers. When I first did my early scores, I worked with a guy named Dan Wyman; he was an electronic music teacher at USC. And he had all these tube-amplifier synths, so I ended up going to his studio for my early scores, like for Assault on Precinct 13 [1976] and Halloween. I would say, “Okay, give me some strings.” [makes string sounds] I had no idea what he was doing, but I could play them on a keyboard, that was the whole trick. Then when I started working with [composer and sound designer] Alan Howarth, he had a bank of keyboards. He’d do the same thing; give me something low and ominous. Alan would fuck around and come up with a sound, and that is what it was. But all this stuff was improvised. The equipment kept improving, the sonics kept improving, everything kept improving. The early stuff was pretty crude.

PORTNER: Crude, but there is something almost like punk, like DIY. What were your specific influences when it came to making those early soundtracks?

CARPENTER: For the melody and chord progression in Assault, the main title theme was shamelessly based on [Led Zeppelin’s] “Immigrant Song.” [hums the song] The score from the original Dirty Harry [1971] was also stolen from “Immigrant Song,” and so I just took it. It sounds so raw nowadays [laughs].

PORTNER: It’s great. I was just listening to it. Do you remember what you used for the drums and rhythm sounds?

CARPENTER: I have no clue. It’s all electronic! “Give me a drum.” You know, “Here’s the beat.” I didn’t know anything. I still don’t know anything, thank God.

PORTNER: Are you always thinking about the scenes in the film when you’re making the soundtrack? The main Halloween theme and some of the more melodic stuff sometimes seems to come out of the blue.

CARPENTER: Generally, it’s improvised. I’ll just start playing chords or tones or drones or whatever and get a chord progression going and then just build on it, keep building and the melody comes out. I had three days to record the score for Halloween, which was a big improvement from Assault, which was one day.

PORTNER: [laughs] That’s crazy.

CARPENTER: Three times as much time! I asked for a beat first and then I sat at a piano and kept playing. All I did was play octaves. In those days my chops were a little better than they are now, so I could keep up with the time, and it was pretty fast. Then I added strings and on and on.

PORTNER: So you just kind of built it as it went on.

CARPENTER: Built it up. I never watched the film while I put the music together for Halloween. That was before all the technology. I just threw something on there. I was cheap and fast as a composer. I didn’t have any real training at orchestrations.

PORTNER: What about music lessons? Wasn’t your father a composer?

CARPENTER: My father was a professor. He tried to teach me the violin and I had no talent at it; it’s the most difficult instrument to learn. I graduated to the keyboard, I can play half-assed keyboard.

PORTNER: Growing up, your soundtracks were a big influence on me musically. Do you think of those soundtracks as separate from the movies?

CARPENTER: I don’t, because I’ve never listened to them alone. They’re functional.

PORTNER: Music can be so manipulating—especially in terms of horror. It’s such an important part of building the tension. I just did some additional scoring on a music video and it shocked me how much you can immediately change what you’re watching by putting some music on it. I read somewhere that Halloween wasn’t supposed to have any music on it at all.

CARPENTER: No, no. Before we were recording the music, I showed the movie to an executive as an example of my work so I could get another job. The executive said, “That isn’t scary at all.” [laughs] But with the music, it got a lot scarier. It was always going to have the music. But really, in the end, it’s all instinctual. I grew up with music, in my life and in my head and from my father playing classical music. I had all that swirling around. I had a lot of influences that I recognized early on. For instance, there’s an English composer named James Bernard who composed the early Hammer films—the The Creeping Unknown [1955], Enemy from Space [1957], The Curse of Frankenstein [1957] and Horror of Dracula [1958]. I thought to myself, “What’s so disturbing about this?” I met him later in life and he told me that he’s playing seconds, a musical mistake that grates at you, that puts you on edge.

PORTNER: What about your influences for the soundtrack to Escape From New York?

CARPENTER: I was heavily influenced by a movie called Forbidden Planet [1956]. That’s all electronic scored, the first one ever. It’s mind-boggling. The sound—what is that I’m listening to? What the hell is that? Not a typical movie score. It’s really interesting. Later on, when I actually started making movies, there was a movie in 1977 called Sorcerer by William Friedkin. Tangerine Dream did the soundtrack but, wow, it was real simple—like do do do do over and over again—but all electronic. Wonderful score and a highly underrated movie. I recommend it.

PORTNER: While we’re on the topic, what other movies from that time were game changers for you? I’m thinking of something like the movie and score for Texas Chain Saw Massacre [1974]. Just the noise of that film alone …

CARPENTER: That was a pretty cool flick. It’s also funny. That movie was comedy, in a sense. That guy bitching in a wheelchair when he finally gets his. Definitely a game changer. One movie that showed me it was possible to make a low-budget horror movie was Night of the Living Dead [1968]. When I saw that, I was like, “Wow, that’s really effective, but it’s obviously low budget.” They didn’t have any money but they actually made something cool. That was inspirational to me when I was in film school.

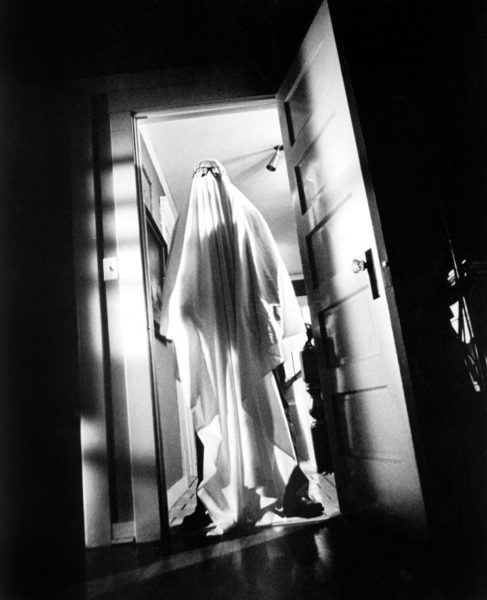

PORTNER: Do you think the stalker is one of the big themes of your films? Like Michael Myers in Halloween.

CARPENTER: No, not at all. Halloween was an assignment. Some killer stalking babysitters is all it was. I created that character and named him after the distributor in London who had released Assault on Precinct 13. His name was Michael Myers and he was one of the nicest men in show business. I took away his character and I made him an evil force.

PORTNER: Your Michael Myers is an iconic character, maybe up there only alongside Jason Voorhees from that time.

CARPENTER: Well, the main influence was Westworld [1973], which had a robot gunfighter. He kept coming back. He wouldn’t stop.

PORTNER: I was that character for Halloween once, actually. [laughs] Do you think the imagination is still flowing in the horror world today?

CARPENTER: It never dies. It just keeps getting reinvented and it always will.

PORTNER: Do you think it’s always been old ideas just coming through the subconscious?

CARPENTER: Not necessarily. You see, horror is a universal language; we’re all afraid. We’re born afraid, we’re all afraid of things: death, disfigurement, loss of a loved one. Everything that I’m afraid of, you’re afraid of and vice versa. So everybody feels fear and suspense. We were little kids once and so it’s taking that basic human condition and emotion and just fucking with it and playing with it. You can invent new horrors. I think Night of the Living Dead was a big invention of a zombie. There were zombies before, but Romero set the bar and everybody rips him off—like The Walking Dead. Vampires like Dracula were evil, but new vampires, we love them because they’re the subject of tweener movies like Twilight. But it will continue to evolve. Right now we’re in a supernatural phase and cheap-movie phase. But everybody reinvents. Your generation took the music that I grew up with and re-formed it, refashioned, reinvented it, and it continues to grow.

PORTNER: Do you think we’re in a cheap-movie phase? People keep telling me that you need millions and millions of dollars to make a movie. But for Halloween, you had a pretty tight budget, didn’t you?

CARPENTER: [laughs] Pretty cheap.

PORTNER: Some of the scariest stuff, and definitely some of the most amazing visuals, have been done for pretty cheap. Was that out of necessity?

CARPENTER: Yes. It began in school. We didn’t have any money. We made movies for nothing. You got your friends and classmates to act in it, you shot it, you were just figuring out how to do it. Okay, I want music on my movie. Well, you can take it from a record or you can get someone from the film department who knows a little bit about music to score. I did a couple of scores in film school, mainly on the piano. And I did it on my own films for nothing. When you have no money, you need invention. So that’s where it started.

PORTNER: Do you think there’s something to be said for starting out on limited means?

CARPENTER: I can only talk about myself, I can’t advise other people. It’s whatever works for you.

PORTNER: What about having complete creative control?

CARPENTER: Oh, that’s huge. That’s the ultimate.

PORTNER: What is success for you? Horror isn’t something that you make expecting an Oscar.

CARPENTER: I haven’t just made horror. I’ve made all sorts of movies. There have been fantasy movies, thrillers, horrors, science fiction. In terms of the ultimate reward, listen, man, when I was a kid, when I was 8 years old, I wanted to be a movie director, and I got to be a movie director. I lived my fucking dream, you can’t get better than that. That’s the ultimate. I don’t need anything. Well, I do need other things, the NBA, video games …

PORTNER: But I’ve also read that you don’t like any of your movies?

CARPENTER: I don’t watch them. If I watch them, I think, “What was I doing? Why did I do that shot that way?”

PORTNER: Is there one that you think is perfect?

CARPENTER: No, nothing’s ever perfect. I like them all; I just don’t want to have to see them again.

PORTNER: When I watch your films, I find a strange connection between them in terms of twisted psychologies.

CARPENTER: That’s more about you than me. To me, my characters are just fine.

PORTNER: Michael Myers is fine? [laughs]

CARPENTER: He’s not really even a character. It’s the absence of character that makes him frightening; there’s nothing to reach. There’s no dealing with it. There’s nothing to touch. It’s a force of nature and a force of evil. I’d say all of my characters are grounded in reality to begin with, then they may go on various adventures and get unhinged. The protagonists, or heroes, are usually reality-based. The antagonists could be the monster from outer space or Michael Myers or a 2,000-year-old Chinese wizard, it doesn’t matter. But I think you have a tendency to intellectualize all of this. Movies are like music. Actually, they can’t be, and that’s too bad.

PORTNER: It’s funny you say that because for me, it’s too bad music can’t be like movies.

CARPENTER: Are you kidding?

PORTNER: For me, playing music and listening to music and creating music is very environmental. It creates a certain environment; it sets a specific mood.

CARPENTER: In movies, it all starts with a story. What’s the story about? If the story is about a little girl who goes to the candy store and goes home happily, that’s one kind of a movie. If that little girl goes to the candy store and behind the counter is some evil guy and she runs home screaming, that’s another movie. What is the story about and how do you support the story with music? That’s what it’s about. It’s a whole different ball game than, “Let’s sit down and make some music together.” In that sense, I always go back to the basics. Everybody gets together so we have a feeling as a band and play a little blues. Blues is great for that because everybody can join in; it’s almost like the universal language of music. Then we can branch out and start doing more complicated things. That’s what I started my kids with; they were drummers, guitarists, bass players. “Come on, guys, let me teach you some I-IV-V chord progression. Let’s do it in E because that’s the easiest chord of all and a great key. Learn those basics and you can go to them any time you want.”

PORTNER: So you enjoy just playing music.

CARPENTER: Hell yeah. It’s fun. And I’ve played in many groups—none as successful as yours, though.

PORTNER: On the new album, there’s a lot of nice keyboard riffs happening like that. And you just structured it and built it up day to day?

CARPENTER: It’s just a day to day. It’s that pure musical moment. For movies, you have to plan everything out; you have 150 people looking at you on set.

PORTNER: Have you become keenly aware of clichés in film scores? Like, do you ever want to turn off a movie that has a bad score?

CARPENTER: There are two broad themes in scoring movies. One is the original idea, the way they used to do it. It was popularized by a guy named Max Steiner. He scored King Kong [1933]. It’s called “Mickey Mousing.” He scores every footstep, bum bum bum. Scared. Lonely. Every emotion is scored. That’s what’s going on today. There’s all this bravery music when the characters become brave or the sad, dead-baby music when people are sad. Another way of scoring, and it’s not necessarily a big, popular way, is to hold back and do minimalistic stuff and set moods and don’t tell the emotions to the audience. Set a general mood, but don’t score everything. I get tired of the Mickey Mousing. But can it ruin a movie? I’m just like everyone else. I want to get lost. Please, let me get lost in the movie, let me get with the characters. I’ll forget all about everything. I’ll do all that stuff.

PORTNER: Are there any topics that are too taboo for film? Has anyone gone too far in your eyes?

CARPENTER: Child pornography is taboo. There’s nothing to say about it. Now, there are really no such things as snuff films. That’s a legend. But movies are like pieces of dreams, and we don’t need to go into those dreams. Those dreams are beyond. Child pornography—it’s horrible. Human suffering is a horrible thing in real life. I enjoyed the Saw films because they had a sense of humor, but I watched Hostel [2006], and after a while I thought, “I don’t need this. I’m too old, and I’ve seen too much to go through this anymore.” It’s just too cruel.

PORTNER: Do you think there are topics that people should explore?

CARPENTER: I don’t know. It’s up to you. I think the world is waiting for you to direct a movie. Make a Hollywood movie.

PORTNER: I would love to make a horror film.

CARPENTER: Don’t make a horror film—make a love story! Make something that’s far away from you.

DAVE PORTNER, A.K.A. AVEY TARE, IS A MUSICIAN AND FOUNDING MEMBER OF ANIMAL COLLECTIVE AND AVEY TARE’S SLASHER FLICKS.