SUPERSTAR

Joe Dallesandro Tells Bruce LaBruce About Life as a Warhol Superstar

As an aficionado of the Warhol Superstars (several of whom I and my fellow Toronto queercore coconspirators emulated in the ’80s), it was with great alacrity that I jumped at the chance to interview the mighty Joe Dallesandro, aka “Little Joe.” I had actually met Joe before, back in 1998 when I photographed him for Index magazine. When my friend and I picked up Joe outside of the Hotel Brevoort, an L.A. apartment building he still manages, he wasn’t in a great mood. To break the ice, I asked if he knew the history of the building. “Yeah,” he replied. “Somebody built it and now people live in it.” I had never heard anything put so succinctly. After we plied him with Taco Bell, however, his disposition shifted, and, gentleman that he is, we ended up having a very pleasant and professional photo shoot.

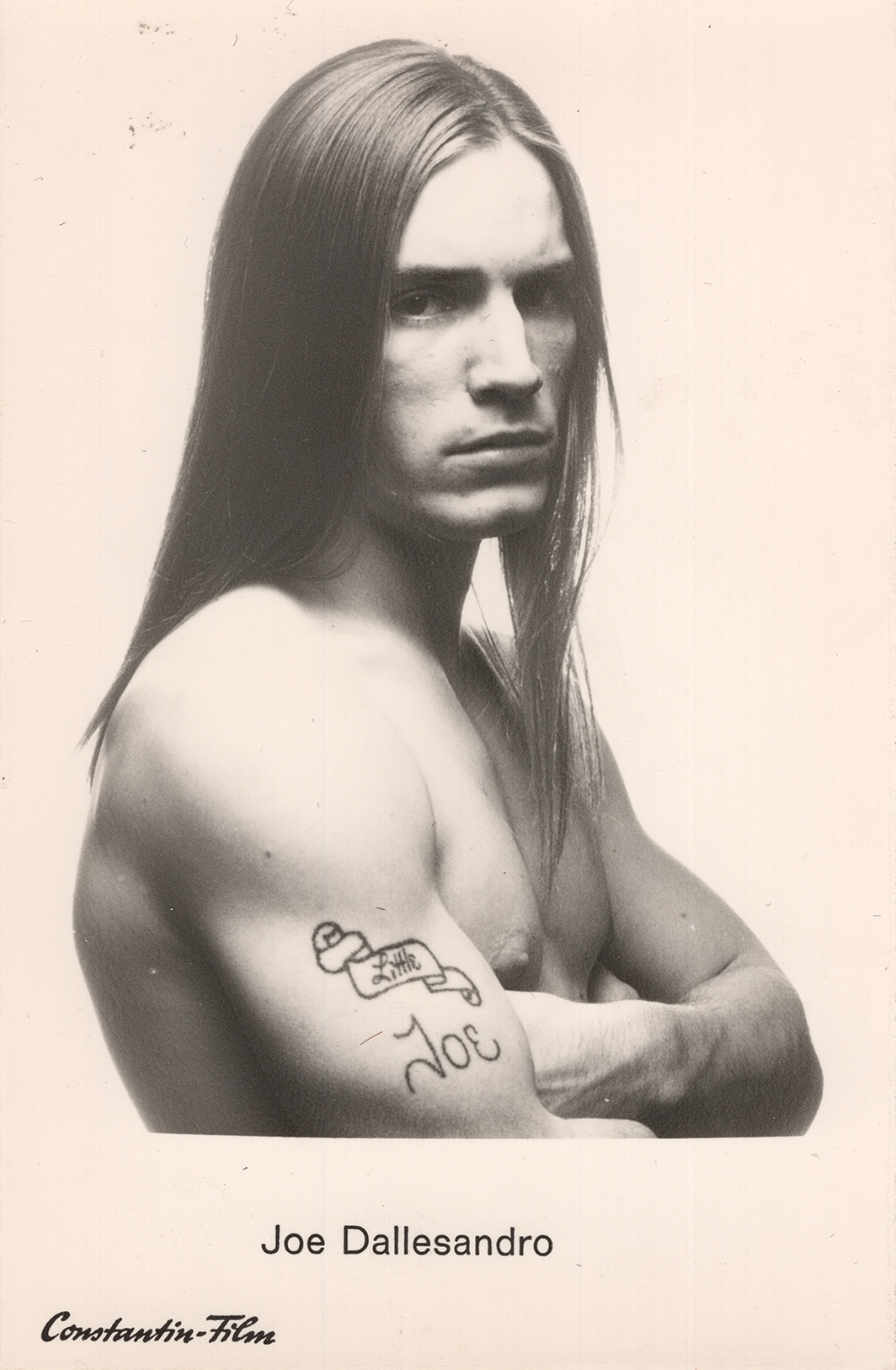

Besides, this wasn’t his first time in front of a camera. Joe Dallesandro, with his muscular physique and rugged good looks, first became known for playing a series of hustler or hustler-adjacent characters in the Warhol movies directed by Paul Morrissey. There was Flesh (1968), Trash (1970), and Heat (1972). Those were followed by the Warhol/Morrissey horror pastiches Flesh for Frankenstein (1973) and Blood for Dracula (1974), both opposite the great Udo Kier. Many know him solely for those performances, but Joe acted well beyond the Warhol years, including more than a decade working as an actor in art and exploitation films in France and Italy. Film geek that I am, I did my best to focus on his impressive body of work (and less on, shall we say, the more salacious side of his life). But with Joe, life often imitated art. Joe has always been comfortable discussing his sexuality (he’s openly bisexual, according to Wikipedia), and two of my favorite quotes on the question of one’s sexuality come from Joe himself, in Flesh. When asked by a neophyte hustler if he’s gay or straight, he replies, “Nobody’s straight. What’s straight? It’s not about being straight or not straight. It’s just you do whatever you have to do.” Then, when his inquisitor tells him he’s crazy, he responds, “Everybody’s a little crazy.” Words to live by.

———

SUNDAY, DEC 3, 12 PM, 2023 LA

BRUCE LABRUCE: Hey, Mr. Dallesandro. How are you?

JOE DALLESANDRO: I’m good. You can call me Joe.

LABRUCE: Okay, Joe. Thanks for taking some time on a Sunday afternoon.

DALLESANDRO: This is my day where I have time to take. I can do anything I want on Sunday.

LABRUCE: Oh, cool. So what keeps you busy on the other days of the week?

DALLESANDRO: I run a building. I collect rents and schedule repairs, and I make sure my place doesn’t fall down.

LABRUCE: And that’s the Brevoort.

DALLESANDRO: Yeah. It’s just a regular building.

LABRUCE: But it has an interesting history. The Black Dahlia lived there with her boyfriend a year before she was murdered. In fact, I made a film called Hustler White, where I chased Tony Ward down the street and over a wall. It turns out it was the Brevoort.

DALLESANDRO: Oh, wow.

LABRUCE: You’ve met Tony Ward, haven’t you? I saw some pictures of you two on your Twitter.

DALLESANDRO: Yeah.

LABRUCE: Hustler White [1996] was an homage to you, in a way—your appearances in the Paul Morrissey movies Flesh [1968], Trash [1970], and Heat [1972]. I’m a big film geek, so I’m going to ask you about some of your movies. But first, there’s a story about you stealing a car when you were 15 and going on this crazy car chase with the police through the Holland Tunnel.

Publicity still of Joe Dallesandro and Sylvia Miles in Heat, 1972.

DALLESANDRO: True story.

LABRUCE: You got shot in the leg. How painful was that?

DALLESANDRO: It wasn’t painful at all. I didn’t even know I was shot until I saw blood. Put my finger down to feel what was going on, and it went into my leg. So that was creepy. The bullet was still inside. I had to go to a hospital and get it taken out.

LABRUCE: Wow. Did you flag down a car or walk?

DALLESANDRO: Somebody had just jumped out of their car and left the motor running because it was wintertime. I had just thrown out a bunch of keys and didn’t want to get caught with them. I ran across the street, jumped into the car, and took off. I had to follow the signs to my neighborhood because I didn’t know where I was. I made it home, and my father said, “You need to go to the hospital.” And that’s what I did. I guess there was a bulletin about somebody going through the tunnel in a stolen car so the police were at the hospital. They said, “You got to confess. We know that was you.” I confessed.

LABRUCE: Did it seem like a movie when you were experiencing it?

DALLESANDRO: No. It just seemed like a scary thing, like, “I’m in big trouble now.” So that was my horrible childhood, which led me to a reform school—or a work camp, which is what it was.

LABRUCE: What kind of work?

DALLESANDRO: Forestry work, chopping down trees, pruning them so that they don’t cause fires.

LABRUCE: So not the worst work that you could have done.

DALLESANDRO: No, but when you’re 15, you should be in school. You shouldn’t be in a place with a bunch of 18-year-olds. But I learned how to use an axe at a very young age, so that was useful later in life.

LABRUCE: That pops up in some of your later Italian films, where you’re in gardens and working with tools. Some of those films seem almost based on your life. There’s one called Season for Assassins [1975].

DALLESANDRO: Oh my god.

LABRUCE: A pretty interesting film with [actor] Martin Balsam, where you’re going around with these other tough street guys creating havoc, and they’re raping women and stealing from rich people. Was that something where the director decided, because of your background, that you would be perfect for this role? Or did it just happen that you were attracted to it?

DALLESANDRO: I decided whether to do them or not. I could usually tell in the first 10 pages of the script. That was after I did the Paul Morrissey films in Italy, Flesh for Frankenstein [1973] and Blood for Dracula [1974]. I was signed to do two other films there.

LABRUCE: There’s one called The Climber [1975] and Born Winner [1976]. Do you think they were aware of your background and that you were a wild kid, and that’s why they offered you the roles?

DALLESANDRO: No. I think the reason they chose me is because of the work I’d already done with the Warhol people, Flesh, Trash, and Heat. One director wanted to be the first one to work with me over there. He was upset when I worked with another Italian director first, but we still did a movie together.

Publicity still of Joe Dallesandro in Trash, 1970.

LABRUCE: Martin Balsam is such a legendary actor. Did he leave an impression on you?

DALLESANDRO: He was, to me, a true actor. He was very, very spoiled. See, I was a different type of person, a regular guy, and these people were movie star types, which always bored me. I’ve had an actor here in my building once say to me, “Don’t you know who I am?” And I just laughed my ass off because who gives a shit who you are? You’re a tenant.

LABRUCE: But Balsam seems like a real professional. He’s one of those guys that probably just goes in, does the work, and gets out.

DALLESANDRO: That’s the way he was, but he was also very angry with crew members if he felt they weren’t doing their job right. He was pretty tough to work with, but thank god I didn’t have to work with him that much.

LABRUCE: You’ve played so many crazy characters. In one film called One Woman’s Lover [1974] you blow up a rabbit. Do you remember that?

DALLESANDRO: Oh yeah, I’m supposed to be a fascist or something.

LABRUCE: You’ve played a lot of sadistic characters. And sexually sadistic characters, like in La Marge [1976]. Was that coming out of the Warhol thing where you were associated with Frankenstein and Dracula?

DALLESANDRO: La Marge starred Sylvia Kristel and myself. She was really famous for her films in Paris, like Emmanuelle [1974]. So it fit that I should work with her. But by the time we came to do our film together, she wanted to be a nun. She didn’t want to do any nudity or anything like that anymore, so the only one who appears nude in that film is me.

LABRUCE: Which happened a lot, I think. You’ve talked about how you’d rather just take your clothes off than have people trying to talk you into it.

DALLESANDRO: I didn’t look forward to doing any of that. It’s just that it appeared in the script, and I said, “No problem. I’ll do it.” But there are a lot of films with no nudity. The only thing I wanted to do in my youth that never happened was to make a cartoon, something that my child could see.

LABRUCE: You worked nonstop in Europe through the ’70s right up until the early ’80s. At that time Europe was very sexually libertine. There was a lot of open nudity and sexuality in the culture. That must have played into all these roles.

DALLESANDRO: I assume so. When I started my career over there, I didn’t want to make any more art films. But I was told by a person that was acting as a manager, “Look, Joe, you started with that crowd, and you’ve got to continue with it because people are expecting it.” That’s how the movie with Louis Malle [Black Moon, 1975], and the Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin movie [Je T’Aime Moi Non Plus, 1976], came to be.

LABRUCE: Do you have an impression of Serge Gainsbourg?

DALLESANDRO: Working with Serge and Jane was one of the best experiences I ever had. It was a good movie, before its time.

LABRUCE: It’s beautifully shot. Same with the Louis Malle film, Black Moon, which is so surreal, with nude children running around and goats and ostriches. What was the set like?

DALLESANDRO: The two things that Louis had trouble working with were the animals and the children. You can’t control either. With actors, you can tell them what you want and can get them to do it. You can’t tell a pig what to do, and you can’t tell children what to do. But it was fun to shoot.

LABRUCE: It’s very dark, with the war metaphor.

DALLESANDRO: Men and women fighting against each other. But we shot the film at his home. It was cool. He had set up a giant tent for feeding us lunch, and we had a great chef who prepared food for us. They don’t think anything about drinking wine at meals because that’s like someone having a glass of milk. Then they’d start back up working just fine.

LABRUCE: I read somewhere that you like to hang out with the crew more than the cast.

DALLESANDRO: I didn’t like producers, man. They annoyed me because they thought they controlled everything. A grip does more for a movie than any producer does. They’re making sure everything on the set is right so the cinematographer can get the picture he wants and the actor can do his scene the way it needs to be done. And they’re pretty cool people.

LABRUCE: It can be boring to make a movie, so it’s nice to have people you can talk to.

DALLESANDRO: Yeah. Otherwise you pretty much sit down and take a nap between shots.

LABRUCE: When you came back from Italy, you went to Hollywood and were quite successful working there. You worked with some great actors and directors like Richard Pryor [in Critical Condition, 1987] and Malcolm McDowell [Sunset, 1988].

DALLESANDRO: These were all super people, man. And it’s not like I’m some character. I’m just Joe. I can play Joe real well, so if you need somebody to play Joe, I’m good at it.

LABRUCE: What was working on television like?

DALLESANDRO: The speed was more like underground movies. With a bigger movie, you’re working at a slower pace, and there’s more time taken into each shot. With television, you have to get more done in a day.

LABRUCE: Looking back at the Warhol films, you’re one of the last remaining Superstars. I’m wondering about those amazing movies like Lonesome Cowboys [1968], which just seems like a complete lark and so much fun. Where was that shot?

DALLESANDRO: Arizona. And shooting with Andy was a lot different than shooting with Paul [Morrissey]. Paul had at least tried to put a story in it. With Andy it was just turning on the camera and letting us go. It was fun shooting with him, but the star of that film would be the one who talked the fastest and the loudest.

LABRUCE: So that would be Viva.

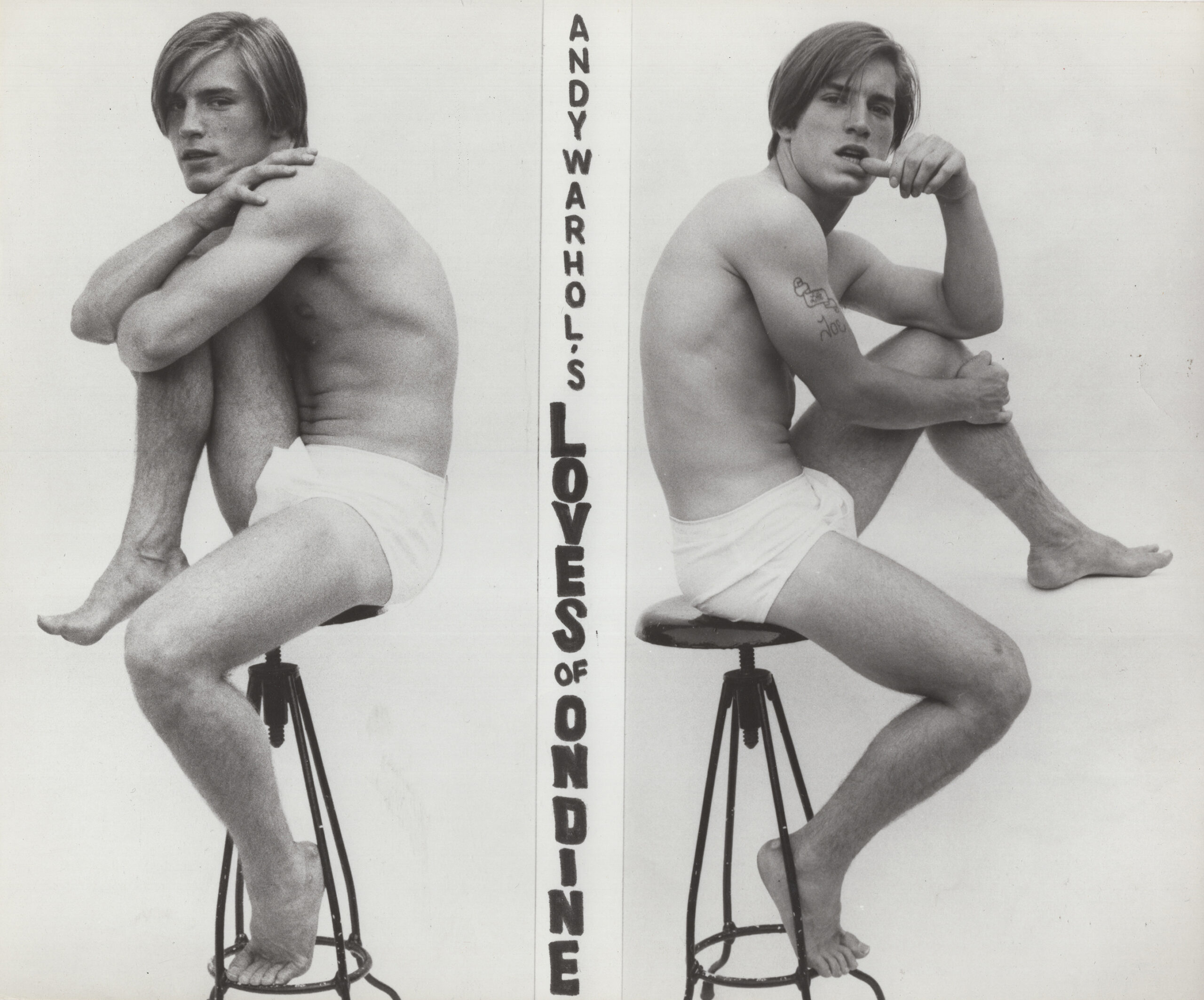

DALLESANDRO: [Laughs] That would never be me because I didn’t talk at all. So yeah, that was Viva. And Taylor Mead, who was pretty cool. There was Eric Emerson, who was a dancing hero, and Louis Waldon. I was the youngest, so they all thought they were directing me, telling me what to do, that I’ll look good if I do this. I didn’t care how I looked. The first movie I made was with Andy, he was shooting a 24-hour movie that was only shown once in its entirety. That was after Paul had cut a small movie out of it and made The Loves of Ondine [1968]. That was the first film I made with Andy, which was a strange, interesting little role that I played.

LABRUCE: What was Ondine like?

Publicity still of Joe Dallesandro in Lovers of Ondine, 1968.

DALLESANDRO: He was fun to work with because he was playing a silly character, married to Brigid [Berlin]. And we did just a small scene of me teaching him wrestling, and it was silliness. So when Paul came over with a release for me to sign, I thought, “What? This is ridiculous. This is never going to show as a movie anywhere.” But it did, to my surprise. And that’s when I began working with them. I went to work at the Factory as a bodyguard or someone to let people in and out of the place.

LABRUCE: Were you literally standing outside the Factory?

DALLESANDRO: I was the doorman. I sat at the desk and buzzed you in. After Andy had been shot, we built a thing around the elevator. So you came in off the elevator and then you were in a small box of a room and I would buzz you through a half-door into the Factory.

LABRUCE: Do you remember Valerie Solanas [the woman who shot Andy Warhol] coming in?

DALLESANDRO: I came in after she was gone. They’d just taken the last person away in the ambulance. That’s when I showed up and thought, “Well, it looks like I don’t have a job, because I wasn’t here to do any protecting.” Later she was back on the streets with a whole shopping bag full of guns. They arrested her, but she never spent any time in prison. It was more that she was crazy and somehow if you get well from being crazy, you’re back out.

LABRUCE: Is there anyone from those days you’re in touch with, like Paul Morrissey?

DALLESANDRO: No, I don’t talk to Paul. I don’t think he’s so coherent anymore. His niece takes care of him.

LABRUCE: The director of Season for Assassins, Marcello Andrei, is still alive. He’s 102 years old.

DALLESANDRO: Wow. That’s wonderful. I love when anybody is still around.

LABRUCE: You made 55 movies in your career, which is pretty unbelievable.

DALLESANDRO: I don’t remember all the movies I did, but they kept me fed. But you made a lot of movies too, and it’s harder for directors than for actors. And you’ve got a long life ahead of you, man. I’m at the end of mine.

LABRUCE: You’re not that old, my friend. Seventy-five is the new 50. And you’ve had a whole career and a family. You have two kids, three grandchildren. That must be really satisfying.

DALLESANDRO: Yeah, but I wish I’d have spent more of their childhood with them, but that wasn’t meant to be. But we do spend our later years together.

LABRUCE: Do you ever miss New York?

DALLESANDRO: No. I was born in the South, so my body just wants to be somewhere warm. I couldn’t stand the cold of New York. It’s horrible. I don’t even like watching snow on TV.

LABRUCE: If someone came and offered you a juicy role right now would you take it?

DALLESANDRO: Sure.

LABRUCE: Maybe I’ll try to write something for you.

DALLESANDRO: Oh, that’d be wonderful.

LABRUCE: Do you watch a lot of movies these days?

DALLESANDRO: I have an Apple TV thing, where I watch mostly Disney. I love animation. There’s no violence in it, and any violence they portray in the cartoon is acceptable to me because it’s not real. I don’t watch the news in my old age because it’s just a repeat of stuff I saw when I was a kid. Why do I want to see the same old nonsense? I thought we’d be living in some utopia by the time I was my age because of the people that I knew in my youth. Everybody was smoking marijuana and living a good life and being hippies. I thought when these people grew up, politics would be totally different. Instead it all turned into greed and they’re worse than the people we had before.

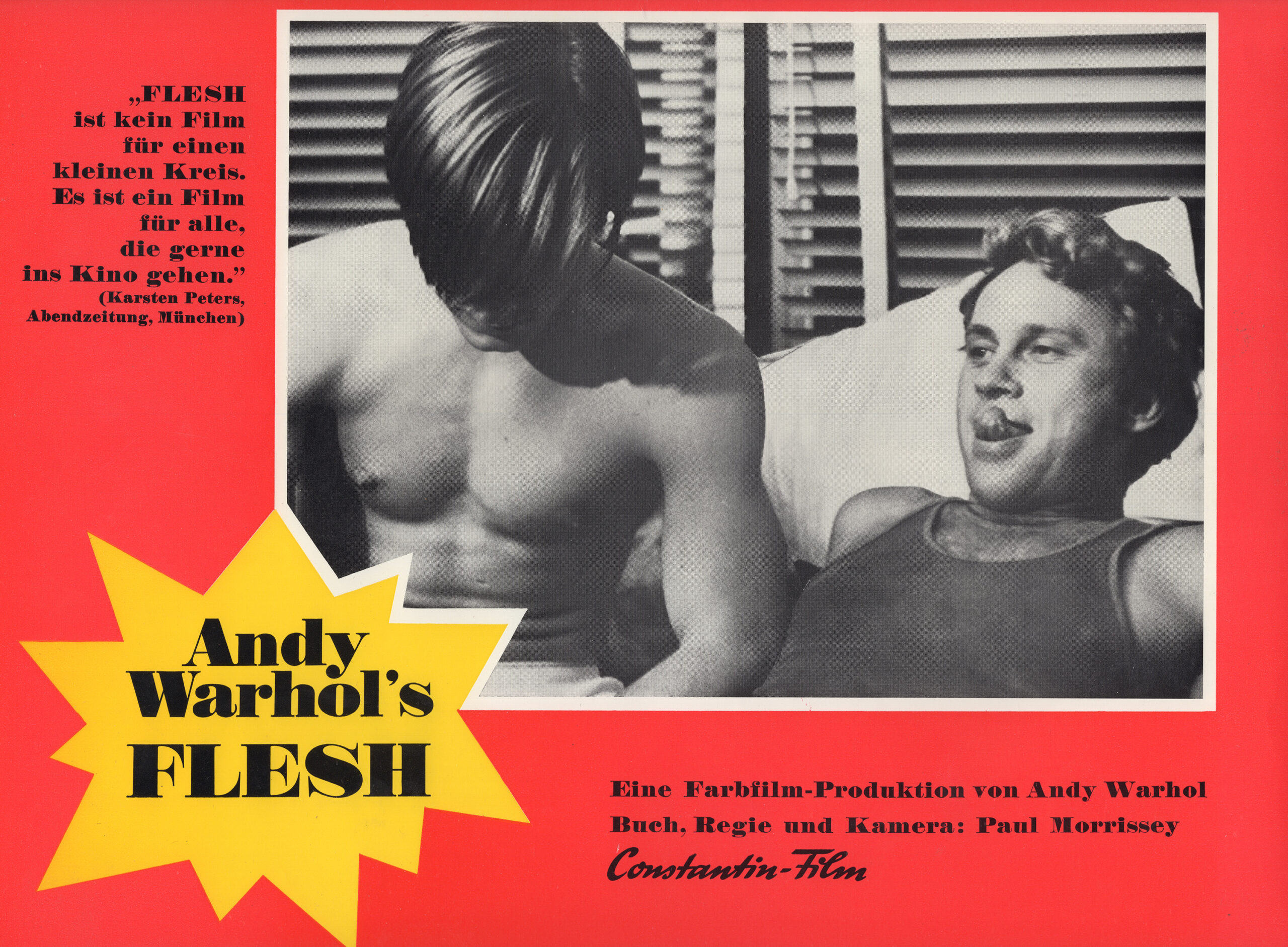

Joe Dallesandro and Louis Waldon in Flesh [1968, German lobby card].

DALLESANDRO: Yeah. We don’t have any of that going on today. Just yesterday at a supermarket down the street from me, somebody came in and had a shootout with a security guard because of road rage or something.

LABRUCE: Where do you think it all went wrong, Joe?

DALLESANDRO: I really don’t know.

LABRUCE: I’ll go right back to the beginning. I’m curious about your debut with Bob Mizer and the Athletic Model Guild. How did you meet him?

DALLESANDRO: That was a pure accident. I was in Los Angeles looking for something that a young person can do, and I met somebody who said, “You should be a model,” not knowing they meant nude modeling, but it turned out that that’s what it was. And it provided me with some money to survive.

LABRUCE: You were only 15?

DALLESANDRO: Actually I was 16, so I was an adult by then. I was a manly man. I had a good life. You were influenced as a director by Warhol films, weren’t you? Along with John Waters.

LABRUCE: Yeah. What was your impression of working on Cry-Baby [1990] with John Waters?

DALLESANDRO: I really didn’t have much to do there, man. I could have done so much more with John. I loved working with him, and I wish we would’ve stayed more friendly with each other, but it is what it was.

LABRUCE: He just got his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Do you have one?

DALLESANDRO: Of course not.

LABRUCE: Somebody’s going to have to work on that. I’m going to start a petition.

DALLESANDRO: I wouldn’t be interested in wasting money on something like that. But I do want to say something. People can order limited edition silkscreen prints of Jack Mitchell’s photos of me on littlejoe.bigcartel.com.

LABRUCE: Okay. Those will make good gifts.

DALLESANDRO: Yes, thank you. It was wonderful talking with you.

LABRUCE: You too, Joe.

Joe Dallesandro in 1970 [Constantin-Film postcard].

———

Photography Assistant: Sam Massey

Hair: Johnny Stuntz using Stuntz Beauty at Uncommon Artists

Makeup: Darian Darling

Archival photos courtesy of The Paul Morrissey Archive.