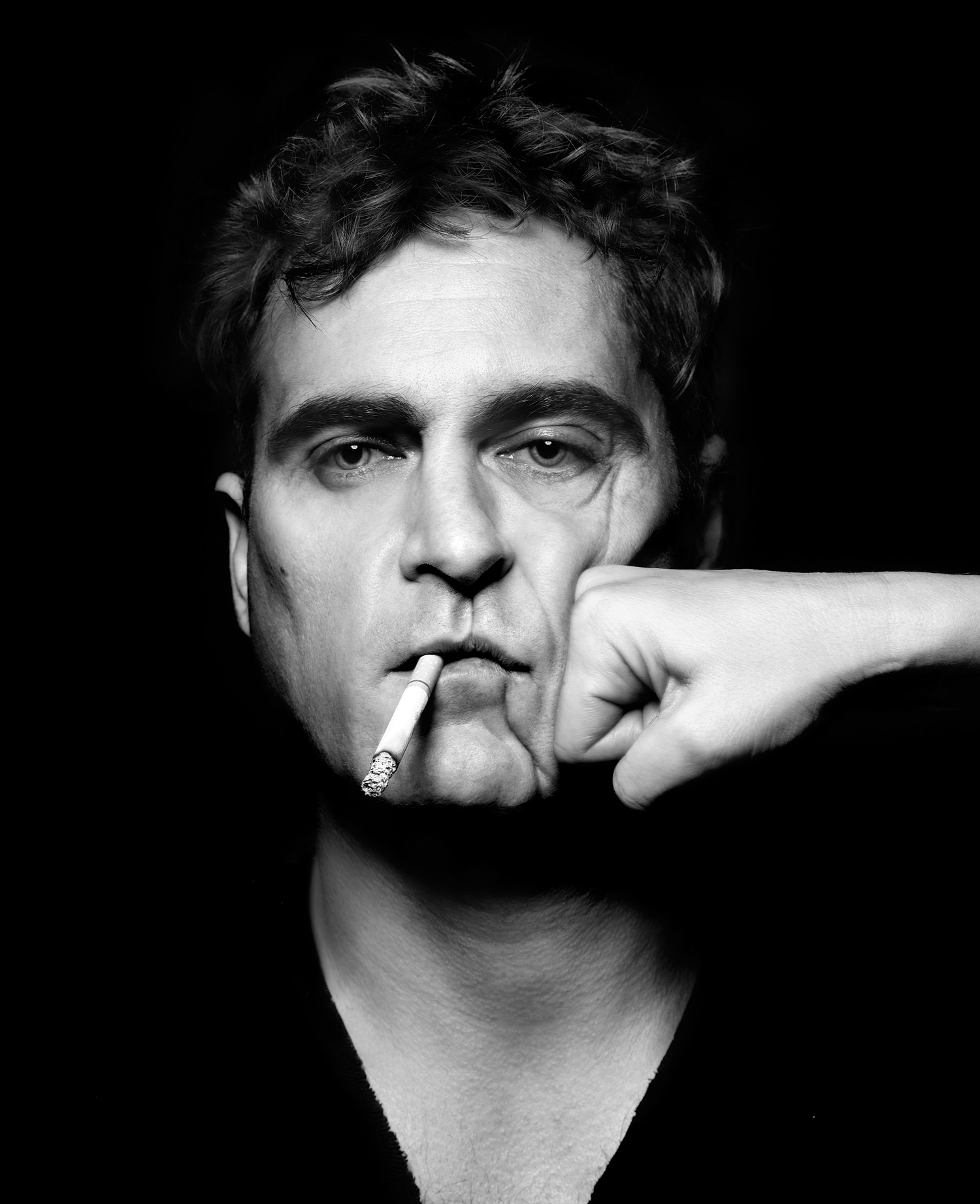

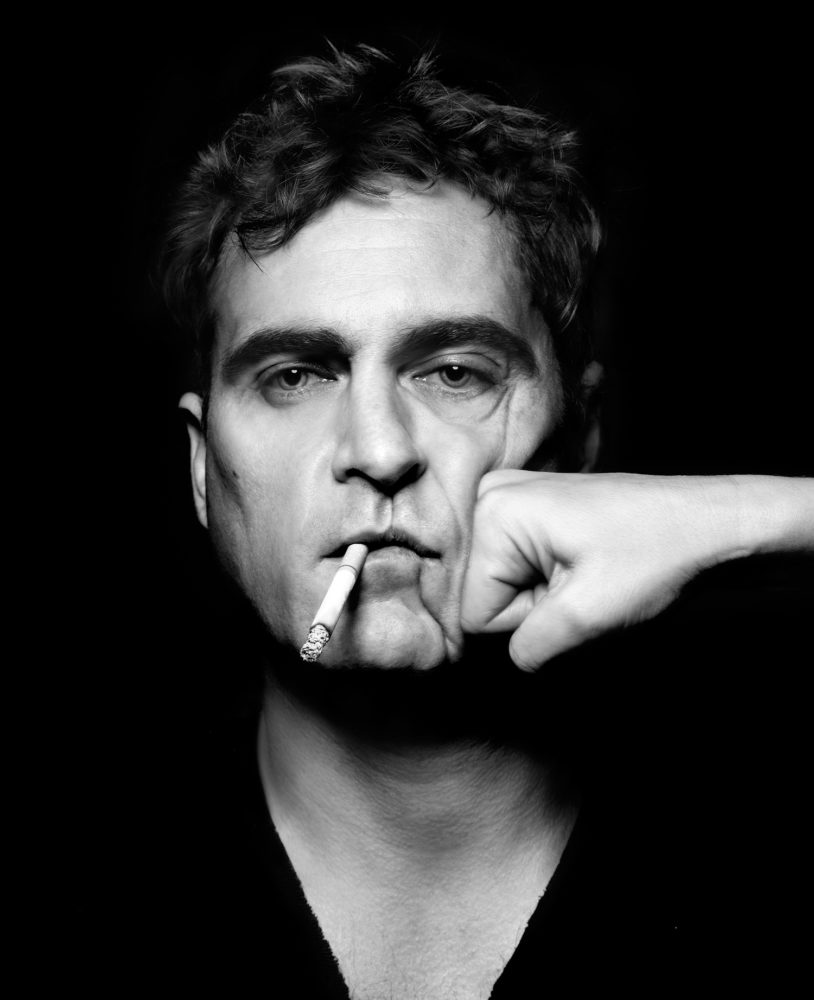

Joaquin Phoenix

“That’s one thing I hate more than anything: nailing it. He nailed it . . . I don’t want to nail it. I want to go into the courtroom and feel like I might lose the case.” – Joaquin Phoenix

When I show up 15 minutes early to meet Joaquin Phoenix for our interview, he is already there—and based on the cigarette butt in the ashtray, he’s been waiting for me for a bit. The notoriously reticent Phoenix regards me with a chuckle: “Good luck with this conversation,” he says, smiling.

Phoenix, 37, has made a triumphal return to the movies with his starring role in Paul Thomas Anderson’s intimate epic, The Master, in which he plays the lost and yearning Freddie Quell, a World War II veteran trying to clear his head when he meets the charismatic Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), an author and academic whose oratorical gifts are so silken that he seems to even be hypnotizing himself. The Master trails Freddie in his search for meaning in postwar America. But while Phoenix himself can be an evasive talker, his intent does not appear to be slipperiness or obfuscation. He simply seems uninterested in pimping himself, and is more prone to dropping his awe of Hoffman or his nervousness about working with Anderson; if Phoenix ever writes a Master making-of diary, each entry will likely start with, “Today I’ll probably be fired . . .”

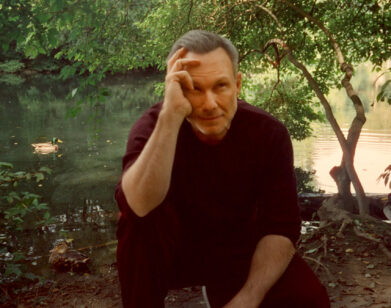

Anderson made Phoenix’s eager restlessness central to Freddie—and The Master as well. I can’t think of another filmmaker whose work focuses almost entirely on anxiety. It may be something that he has in common with Phoenix, who took testing one’s limits to a new level-high or low, depending on your feeling about it—with I’m Still Here (2010), his collaboration with director, best friend, and brother-in-law Casey Affleck. Despite the haze that he created around that film—in which he announced plans to give up acting for a career in hip-hop—Phoenix wants to be understood; and in its aftermath, he wants audiences to be surprised by his performances while they’re still current. So even as Phoenix claimed that he had nothing to say (which was hardly the case), he was generous with his time and did something interview subjects rarely do: easily 20 percent of the conversation was his questioning me. He stayed long enough to be late—quite late—for another appointment, and even took a moment to chat up another lunch guest at the Sunset Tower Hotel when he excused himself from the table and bellowed, “You never call, you never write, you skipped my Bar Mitzvah,” as he strode over to give a warm hello to Richard Lewis. After Phoenix exited, Lewis leaned in and said of his old friend, “He’s a great actor—and a good man. He’s been away too long.” I had to agree.

ELVIS MITCHELL: What do you see in movies when you watch them that makes you think, This is a director who I want to work with? Or does that ever occur to you?

JOAQUIN PHOENIX: I actually like it when I’m not really familiar with the director’s work.

MITCHELL: Really?

PHOENIX: Yeah. I remember doing a movie and the director gave me a DVD of one of his films to watch. We had this meeting, and I was like, “I like him. I want to work with him, so I don’t want to watch the movie.” I don’t know . . . I was probably foolish.

MITCHELL: Do you want to be surprised when you work with someone? Is that what it is?

PHOENIX: [pauses] I don’t know . . . I don’t know why. Obviously, there are some people, like Ridley [Scott]—I’d seen Blade Runner [1982] and Alien [1979] growing up, so I knew those films before we did Gladiator [2000]. But I guess I just want to base my decision off my interaction with the person, kind of . . . [sighs]

MITCHELL: So it’s not just a matter of working with somebody’s résumé. You want to work with the person.

PHOENIX: Yeah. I mean, I guess the smart thing would be to do both, but maybe it’s just laziness on my part. I don’t know. I just don’t want to have to sit through a movie. [Mitchell laughs] What the fuck? I don’t know . . .

MITCHELL: Do you find it tough to connect with movies? Would you rather be making them than watching them? Is that what it is?

PHOENIX: Definitely . . . Well, imagine being, like, a magician, and then going to watch other magicians. Sometimes you watch crap magicians. Every once in a while you see a great one and you’re like, “Oh, fuck. That’s cool.” But as a magician, you know everything that happens, and it just takes you out of the whole thing. So when you get a movie where you don’t see any of those things, that’s when it’s awesome. You’re just caught up in the moment. But with so many movies, it’s not really enjoyable.

MITCHELL: Do you think it’s because you started in the business so young and you got to see so much of this stuff happening and were aware of it at a really early age?

For or a while, it was bad . . . casey and I were getting into bigfights about it—really intense—and I was like, ‘I’ve worked for yearsand this movie cost me money and i’m going to lose my house.’ Joaquin Phoenix

PHOENIX: Maybe. But it’s weird because for as long as I’ve been making movies, I really don’t know a lot of the technical side. I mean, I’ve actively and consciously tried to avoid learning that stuff. I just want to be open and receptive to what’s happening in the moment, and I don’t want to force anything. Dishonesty is so ugly on film. You just act, and it’s so ugly, and I don’t want to do that. I mean, everything that they teach you when you’re a kid about acting is completely fucking wrong. They tell you to memorize your lines, follow your light, and hit your marks. Those are the three things that you shouldn’t do. You should not learn your lines, you should not hit your mark, and you should never follow your light. Find your light—that’s my opinion. Everyone else will tell me I’m wrong, but that’s my opinion.

MITCHELL: When did you come to that conclusion? When did that happen for you?

PHOENIX: Really, before I’m Still Here. Obviously, I’m Still Here just made me really solidify what I felt about the kind of acting that I wanted to experience. I’d done a run of movies around Walk the Line [2005], and I just didn’t want to do that kind of acting anymore.

MITCHELL: Are you looking for honesty?

PHOENIX: In terms of acting?

MITCHELL: Yeah.

PHOENIX: Because sexually, no, I’m not. [Mitchell laughs] But in terms of acting? Please lie to me . . . No, yeah, of course.

MITCHELL: Well, what you’re saying seems to be that you reject all of these things that are telling you to go out and basically find a way to repeat the same thing over and over. So are you trying to find a way to make it different for yourself each time then?

PHOENIX: I don’t know what would make it different each time. Each time is different, and you can’t overthink things. That’s another danger, to go, “Well, I’ve got to do something different . . .” Because I want to be true to what the thing is, and if that means that it’s similar to something else that you might have seen me do, then that’s fine, too. I don’t give a fuck. I don’t need to look different or do an accent. That’s not what I’m after. I’m after . . . I don’t know exactly what I’m after—it’s just a feeling that I’m chasing and I don’t know what it is. But I think the only way I really get it is by feeling that there’s no real control and that there’s a certain amount of danger. Otherwise, when I go through a scene over and over, I start going through dialogue, and then I start putting inflections on things and going, like, “Oh, what if I did this?” And it becomes fucking smarty pants thinking he’s being clever by doing some shit. But I don’t like that actor; I don’t like that in myself. I can see that from years ago, like, “You’re just making a face and trying to say that you’re angry right now and you’re shoving that across the fucking screen.” It’s embarrassing. So I just want to capture things that I haven’t figured out, that I don’t understand. That’s what the process is. I told Paul in the beginning, “I’m not going to modulate at all. I’m not going to be adjusting things. I just have to find what I feel and you’ve got to tell me to pull way back or go forward or if it’s too much. But I’m going to go in and do what I feel in the moment.” Sometimes it’s wrong. Sometimes you come into something with too much energy. I mean, look, I’m very fortunate because I’ve worked with these amazing directors that I’m able to do that with and really find the truth with, because that’s what they’re after as well. But if the director’s not after it, then forget it. There aren’t fucking good actors. It’s all the director. It’s so funny when people say it’s good actors—and actors really believe it and shit. You’re completely hostage to the director. So the director is the most important person to me. I work for them. My job is to help them fulfill their vision. But I like being an employee. I like making somebody happy—and if they’re not, then I’m crushed.

MITCHELL: How much of it is making them happy and making yourself happy?

PHOENIX: I’m probably never going to be happy . . . Well, I’ll tell you what, that’s not true. Here’s a guarantee: If I’m happy about something that I’ve done, then it’s going to be very bad. That’s a guarantee. Without fail, if I ever go onto a scene and say, “I’ve fucking got it,” then it’s the worst thing in the world. I think you’re just looking for life. Obviously, there’s a lot of money put into these movies, so everyone wants to figure out how much time they’re going to spend on these things and everything is very controlled. The idea is like, “We want to know that this is the third act and this guy is making a speech in front of the jury and it’s supposed to hit like this and that’s nailing it, right?” But that’s one of the things that I hate more than anything: nailing it. He nailed it. Well, that guy came in, he said, “Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” and . . . boom! He fucking nailed it. And part of me is impressed with that—one of my favorite actors can fucking nail it—but it’s just something that I don’t want to do. I can appreciate that ability in other people, but I don’t want to be that actor. I don’t want to nail it. I want to go into the courtroom and feel like I might lose the case. I want it to be scary—and it still is. I’m almost 38. I’ve been acting for 30 years. But I still get nauseous the day before and have weeks of incredible anxiety. They have to put fucking pads in my armpits because I sweat so much that it just drips down my wardrobe. For the first three weeks of shooting, I’m just sweating. It’s pure anxiety, and I love it. [laughs]

MITCHELL: How important is it for you to really know the character and immerse yourself in the script before you start shooting, versus finding it as you’re going?

PHOENIX: Oh, I think it’s always finding it as you’re going.

MITCHELL: Is that what it was like for The Master, too? You found it as you were going?

PHOENIX: Yeah. I mean, I would say that it probably takes me two to three weeks before I get anywhere near anything. If I’m going through the script and I feel like I’m starting to really discover that there’s something, I move off of it. I want to move off of it before it gets locked in my brain because I have this horrible thing. You know, James Gray really pointed it out to me when we did The Yards [2000]: I will get into a rut in a certain way that I’ll say a line to the point where you just have to shake the bitch up and find something else because there’s no energy, no life to it. I’m now trying to say what, at one point, I had said with some feeling, but now I’m just trying to copy it. It doesn’t have anything behind it. So I told Paul this—and I’ve told it to every director I’ve worked with recently: “I’m actively, consciously, going to do very bad things in an attempt to take any pressure off it and to say, ‘I don’t know what it’s going to be.’ ”

MITCHELL: As you were reading the script for The Master, did you find yourself surprised by it scene after scene after scene?

PHOENIX: I was just confused. [laughs] No, I was surprised. I mean, it was weird because it’s really perfect that I ended up working on this movie at that particular time. You know, you start a movie out and you read the script and you’re so nervous and you just want to please your director so badly. But the first time I sat down with Paul and Phil [Seymour Hoffman] and we went through a scene, I was convinced that they weren’t going to hire me. I was convinced it was over. I was like, “I can’t believe it.” I got up at five o’clock in the morning and fucking studied through the processing scene on the boat because I knew we were going to rehearse that. I had to try and get it down. It literally felt like an audition. So we went in for the next rehearsal and I was like, “I’m basically auditioning today,” because the day before I was pretty sure Phil was like, “This is not working,” and Paul was going, “I know. I don’t know what to do.” No joke because, dude, for real, here’s the thing: Phil is such a goddamn genius. So you’re sitting there with this fucking genius, and he starts talking, and I’m like, “I can’t follow this guy. I’m not saying anything after him!” He can read a fucking grocery list and you’re just like, “Oh, so captivating . . .” It was incredible to be around him. So I was like, “Fuck, man. They ask me to do this movie, and we do rehearsal, and it’s so bad and Paul is probably doubting it . . .” But, yeah, then we just went back and rehearsed again, and that day I think we talked a bit more and maybe he was like, “Okay, I’ll give him a shot.”

MITCHELL: Do you feel that part of your character in The Master, Freddie Quell, is that he’s never really sure what’s going on?

PHOENIX: Completely. When we were first started, I talked to Paul about Freddie’s motivations for doing certain things, and Paul never had an answer for the character. So it was really frustrating in the beginning of the movie. There was nothing solid or consistent about Freddie. But I’m also a slow learner-real slow. So it takes me maybe halfway through the movie before I suddenly figure out one of the major plot points of the entire film. But it’s like in the scene where homie starts talking about wrestling a dragon. As soon as I realized that I was the dragon, it was much easier. I mean, it’s kind of like my dog. She loves me, right? We’ve got a great connection and I love her. She loves being at my house, and I guarantee that she’d be happier at my house than anywhere else. But if I open the fucking gate, she’s gonna roll, and it’s not because she has something against me. I don’t think she even fully understands what it is, but there’s just something inside of her that’s wild. She might not even want to leave, but it just happens. So as soon as I kind of gave in to that thing, that that’s where Freddie was . . . It’s just impulse. It’s not knowing what’s going to happen next. It’s not knowing why you did the last thing that you did. It seemed like every time we came to some conclusion about Freddie, it felt wrong. It was rather that there were all of these things going on, and he didn’t understand what was pushing or pulling him or why. So as soon as I gave into that . . . I mean, that’s why I was saying it was perfect for me at the time, because that was kind of the approach that I wanted to be taking in acting as well-to not know what it is and to give in to the moment. It’s so rare to get a chance to do that because everything about movies is that we all know that we’re heading to this point-that’s where we have to get. Somebody has to cry at this thing on this line because somebody just died. But it just takes all the fucking joy and the beauty out of it. You’re missing everything.

MITCHELL: It seems like the last few movies you’ve done—Two Lovers [2008], I’m Still Here, and now, The Master—are all about these guys who kind of don’t know where they’re going. Is that something that attracts you? Or is it just this period?

PHOENIX: I guess it might just be this period, but I don’t know. I do like that just because, obviously, it’s more exciting for me as an actor. I think that part of it is that you make so many movies and you start seeing how things are laid out and you just start to get bored, so you start looking for things that feel unknown and exciting. But I don’t know if there’s any end game. It’s just something that I’m doing if I’m going to do it.

MITCHELL: Was working with Casey [Affleck] on I’m Still Here enjoyable and the whole experience making that movie?

PHOENIX: It was and it wasn’t. I mean, we fought a lot. It was really hard working with someone who is that good of a friend. He’s my best friend. I respect him. I think he’s an amazing and talented actor and filmmaker. It was my dream since we were young to work with Casey. But it was very difficult because Casey was really intent on keeping it secret and I, of course, was a bit of a pussy at times, where I was like, “Well, I would like to tell my friend who has been calling me for a fucking month, ‘Don’t worry. Everything is cool.’ ” So we had arguments about that. Initially, it was just basically supposed to be a bad, glorified Saturday Night Live skit. But Casey was really intent on me getting out there publicly and humiliating myself as much as possible. Casey loves uncomfortable humor, awkward humor. We wanted to capture that random moment of like, “Oh, god. Please. I’m not watching this.” So he was really pushing. There were a couple things where I was like, “Nope. I’m not going to Vegas and getting on a stage. I’m not fucking doing it.” [Mitchell laughs] And, you know, we did it and I was like, “Dude, I have to do these interviews and I’m keeping this shit going.”

MITCHELL: Like the Letterman thing?

PHOENIX: Yeah, but I mean, I also did a bunch of fucking print stuff . . . I said the most horrible things about people. I was like, “I’m going to be dealing with this forever.” Someone’s gonna go, “You once said this,” and I’ll have to be like, “Well, what period was that from?” You know? But it was awesome because I never could have done it without Casey pushing me. I’ve been very fortunate in that I haven’t gotten a lot of attention in that way before. A lot of other people probably experience more . . . But for me, it was an excessive amount of attention, and it was intense. I’d never gone online or looked at reviews or at what people have said about me ever doing any of that. But we started looking because we were then reacting to what was happening in the press. So to suddenly become aware of people talking about you . . . It just did my fucking head in, man. [laughs] It was like, “I do not want this fucking experience.”

MITCHELL: Well, it also sounds like you like the idea of being this car that’s going in reverse at 70 miles an hour—that you get some thrill out of that.

PHOENIX: It’s amazing. I mean, we did shit where there are no other takes. There’s a scene where it’s me and then there’s, like, 500 people in a club who don’t know that it’s a scene. We got a guy, Casey’s friend, that we were planting in the audience, and I was just saying, “Be stage right because there’s no way I’m able to see you”—because of the crowd and it’s all dark and I’m up on stage, and I’ve got to have a fight with this guy. So the terror of getting up on the stage knowing that I’ve got to get to the song and then start having a fight and then jumping into the crowd and nobody knows . . . That was one of the most intense things I’ve ever done in my life. I was shaking. But it was an incredible feeling. The dude almost didn’t get in, which I didn’t know about. He had to fight his way up to the front. I think that I even started just yelling down to where he was supposed to be before he was in position. Diddy was also fucking genius.

MITCHELL: Did you let him know that it wasn’t real?

PHOENIX: Yeah, he’s the one we told from the beginning. What happened was that we went to Miami, actually, and we talked to him and told him the whole story—”You know, this isn’t real, but we’re doing this thing . . .” He was really bright because he was like, “Well, you should do songs and stuff for real and take it seriously.” But he wasn’t saying that I should really try and do it. He was like, “Just don’t do stupid, mock things—really try to write a song.” So we went to his house and it was just like, “Will you do this?” and he said, “Yeah, I’ve got to go to this party, then I’ll go and meet you and we’ll do a scene in the hotel.” So I said, “Look, can we also just get you when you’re leaving right now? We’re just going to pretend that we’re pulling up to your house and that you’re leaving and that I missed the appointment, I missed the meeting.” So we ran outside, got in our car and pulled up to his gate and called and said, “Hey, this is Joaquin Phoenix.” And the voice goes, “Oh, he just left, actually.” And then he pulled out and left. So he knew everything, but played it totally straight, and I thought he was fucking genius. There were a bunch of people—I thought that Sue [Patricola], my publicist, was awesome. Her face at Letterman . . .

MITCHELL: It’s got to be tough to go back to doing a regular movie after doing something like that where you’re basically inventing stuff on the fly.

PHOENIX: Yeah, but that’s the idea—I think you can still do that on a regular movie. Even though things are mapped out more in a traditional film, you still can be searching every moment to try to find something, and keep some of the excitement and uncertainty.

MITCHELL: Had Paul seen I’m Still Here?

PHOENIX: Yeah. I think that’s why I got the job.

MITCHELL: Is it really? Did you guys talk about it when you first met?

PHOENIX: Yeah.

MITCHELL: What was that conversation like? Do you remember?

PHOENIX: I don’t really remember . . . Maybe it was just like, “Oh, well, this guy’s obviously a moron. I’ll cast him.” Sort of just, “This fucking monkey will do anything. I’ll just let that monkey sling shit at himself. That will be great.” And that was essentially what I was. Near the end of the movie, he was just calling me Bubbles. [Mitchell laughs] It’s just like, “Let’s see what else I can get my pet monkey to do. Will the pet monkey set himself on fire?” [makes monkey noises]

MITCHELL: I can tell you one of the more tense moments of TV that I’ve ever seen was watching your follow-up Letterman appearance. Just watching you come out for that second appearance where you had to explain to him what was going on with the first . . .

PHOENIX: It was actually fine. It’s funny because I can’t ever really say all the different things that were involved, so I can’t give you an accurate description of what I felt and why. There was a lot going on . . . I can’t really talk about it, but I was just was so relieved that we were finally able to go and not lie. I don’t like lying-I really don’t. So I just felt so relieved to be able to talk about it.

MITCHELL: It always sounded weird to me when you said, “I don’t like acting anymore.” It seems from just watching you and listening to you talk about acting now, you love it, don’t you?

PHOENIX: Yeah.

MITCHELL: What was that like for you to say to people, “I’m done with acting. I don’t like it anymore”?

PHOENIX: Well, listen, there was some truth to that. There are certain aspects of acting that I don’t like. I’m not a person who loves being on set. I mean, I know people that have their espresso machines in their trailers and they like being in there and they put pictures on walls. But I don’t like it. I don’t like sitting around. I don’t like small talk and being around 60 people all day long. So there are many different pieces that are required as an actor that I find difficult. Press and things like that. So part of why we did the movie is because Casey and I would constantly say after every movie, “I’m quitting.” And then of course, it became this running joke of like, “So what do you think you’re going to do?” “Well, what skills do you have besides picking your fucking nose?” So that was always the joke. It was hilarious because it really was quiet when it was starting out. Casey was like, “We’re going up to San Francisco and I’m doing this play. This might be a good time to announce your retirement because there will be press at this thing.” And I was like, “I’m not going.” We literally were not going to do it. But then there we are on the plane, and then we’re at the thing, and there’s the press line. So we walk toward the press line, and I’m like, “Should I do it?” and he’s like, “You should do it right now.” I was like, “Are you sure we should do it right now?” But then Casey walked right up to a camera and was like, “Hey!” and that was it. It was like, “Well, now we have to keep going.” We really just painted ourselves into a corner. That was a really uncomfortable feeling for me though. I thought Casey and I had actually achieved ultimate success with I’m Still Here, if your definition of success is completely destroying your career-which was somewhat the intent. But doing that movie was one of the best things that I’ve done and that I’ll ever do.

MITCHELL: Sounds like it was liberating for you.

PHOENIX: Unbelievably liberating. It’s the best thing I’ve ever done in terms of helping me grow as an actor and having a deeper appreciation for acting. But for a while, it was bad. I was so worried. Casey and I were getting into big fights about it-really intense-and I was like, “Fuck, I’ve worked for years and this movie cost me money and I’m going to lose my house.”

MITCHELL: The funniest thing in the world to me is the idea of a white guy in his thirties going, “Wait—I’m going to go into hip-hop.”

PHOENIX: But it was also a guy who came from a time when hip-hop was rebel music, and it was intense and rock hard and its own thing. It’s been so corrupted at this point, but he’s talking about it like it’s real compared to acting. He just thinks, I don’t want to support that machine anymore so I’m gonna go do this other thing that is pure and raw. Because when I was a kid, hip-hop was pure and raw.

MITCHELL: Like, almost 30 years ago.

PHOENIX: I know, but that’s still what I remember. I loved hip-hop—that’s why I did it, because it’s something I actually knew about. From, like, ’88 to ’94 was my time. Black Moon was a great band. Enta da Stage [1993], Nas’s Illmatic [1994], and Wu-Tang Clan’s Enter the Wu-Tang [1993] all came out within a year, and it was mind-blowing because I was so deep into it. I love hip-hop.

MITCHELL: When you were writing songs, was there a point of view you were trying to get across?

PHOENIX: It was just foolish. You know when people get so desperate to try to make a change in their life that everything is forced and they become really self-righteous? That’s what it was. It was, “I got something to say!” But really, you’ve got nothing to say, and you think if you just keep saying stuff then it’s gonna be profound at some point. Then it’s the feeling of, “Wait, I’m wrong. It wasn’t this other thing that I’m supposed to do. It wasn’t the press, and it wasn’t anyone making me do anything. I’ve just got nothing to offer.” And then it’s like, “Well, I guess if people are desperate enough to accept me in this one thing, I might as well stick with that.” So that’s what it was.

MITCHELL: That’s why when I heard you say, “I don’t like acting,” I was like, “That can’t be.”

PHOENIX: It’s funny because some people that I’ve worked with were more convinced because they were with me in the trailer when I was like, “I don’t want to work anymore.”

MITCHELL: I just thought it was more that you didn’t want to be in the business anymore, not that you didn’t want to act anymore.

PHOENIX: Well, the truth was that I didn’t want to be in the business anymore, but I wanted to act, so I had to find a way to do that. It was like, “We want danger. We want destruction.”

MITCHELL: But that’s what hip-hop used to be. It was dangerous.

PHOENIX: Let me ask you a question. I was just with my mother and my stepfather to do this work with peaceful, nonconflict resolution. They work with a lot of kids, and I was just visiting with them, which fascinated me because this place they were working is this last-of-the-line school, like the one you go to right before you’re in jail. These kids have already been kicked out of every school. So here I am in this class with these kids, and they say, “Talk about what your gifts are this year.” And this one girl is like, “Two hands.” She has two hands—she’s a fighter. And this is a gift, right? But it’s tough because on the way rolling over there I was bumping fucking Weezy—and I love hardcore rap—but I felt supremely guilty. I’m hanging out with this 13-year-old kid, and I’m thinking about me at 13. Is there enough rage and dissatisfaction in your life where it feels like you’re never fucking heard and no one ever gives a fuck about you? I was angry when that was going on, and I was raised where I wasn’t worried about whether I was going to be able to eat tomorrow. I wasn’t worried about my safety—

MITCHELL: You’re not worried if you’re going to be arrested or stopped in the street for no reason.

PHOENIX: Yeah. So I don’t experience any of that. I mean, dude, how can you work in film and still see the overt racism that exists in film and not just be furious all the time?

MITCHELL: You know what? As a black person, you see so much racism. Films are no different than the government, politics—it’s everywhere. It’s not exclusively film. It’s infuriating to see it in film. But my being in film changes things.

PHOENIX: Yeah, but there’s all of this horrible racism that white people don’t even recognize. Did you see Jumping the Broom?

MITCHELL: I’m a black person. Of course I saw it.

PHOENIX: I feel like all white people have to see the film just because I’ve never seen a movie in which most of the white characters in the movie were just working. It was fucking great. It was almost comical. There was a scene during the wedding reception, and there are, like, eight white people just carrying stuff. The main white character with some dialogue was the ditzy, stupid assistant. I enjoyed it so much because you never see that. But that’s something that I think white people don’t notice. They don’t notice that the fourth character is black and that’s what it always is. It’s always happening. It’s just the assumption that, “Well, that’s just a representation of life.”

MITCHELL: But you know what’s also underneath that? A lot of the time you see all this ambition from these black actors and it’s just pouring off the screen. Because they don’t often get a chance to work, and when they do, they don’t usually get a chance to work with other black people. You can just see the pleasure of those actors. I went to see that movie with my sisters and you could see the crowd levitating. People wonder why black kids don’t go to the movies. It’s because, what’s the point? If you don’t see yourself, then why would you go?

PHOENIX: You know, I got this script a while ago for this thing. It was kind of like an action movie, and it definitely dealt with race in a big way. But then it didn’t. Without getting into specifics . . .

MITCHELL: Did the film get made?

PHOENIX: Oh, it got made. But you could not believe that this thing actually got made, because it seemed like it was from the 1940s or something. It’s got this black character in it who was literally always being saved by the white dude because he was, like, cowering in the corner. So I went in and met the director and producer and I said, “You guys realize that your only black character is this guy, and it’s like the most clichéd thing we’ve seen in movies forever.” And they were like, “What do you mean?” And I was like, “You mean you’re not even aware of it?” They didn’t even realize what they were doing. So I said, “Look, I’ll give them a read if the black character doesn’t get killed and is going to make it into the sequel. They have to put him in their sequel, the black character.” So I spoke to the writer and was like, “Dude, be a hero. When this movie comes out in the summertime, give black kids a character they can see themselves in.” But it just didn’t occur to them, and I realized what a battle it is when people aren’t even aware of what they’re doing. I know what that battle is. I’ve done battles like that before, and you lose. So I didn’t do the movie . . . They did keep the black character alive, though. He’s in the sequel-at least, that’s what I’ve heard.

MITCHELL: Was it a successful movie?

PHOENIX: I don’t think it’s come out yet. It’s one of those big action movies.

MITCHELL: So what are you going to do when they put you on the awards circuit for The Master?

PHOENIX: You’re out of your mind, dude. You’re out of touch with what has happened.

MITCHELL: I think we’ve established that you’re the one who’s out of his mind. [Phoenix laughs] You don’t think that’s going to happen?

PHOENIX: I’m just saying that I think it’s bullshit. I think it’s total, utter bullshit, and I don’t want to be a part of it. I don’t believe in it. It’s a carrot, but it’s the worst-tasting carrot I’ve ever tasted in my whole life. I don’t want this carrot. It’s totally subjective. Pitting people against each other . . . It’s the stupidest thing in the whole world. It was one of the most uncomfortable periods of my life when Walk the Line was going through all the awards stuff and all that. I never want to have that experience again. I don’t know how to explain it—and it’s not like I’m in this place where I think I’m just above it—but I just don’t ever want to get comfortable with that part of things.

MITCHELL: You’ve got to have some cool stuff coming your way now, though.

PHOENIX: Yeah. I finished something this summer.

MITCHELL: Is that the thing you did in China?

PHOENIX: Yeah. Spike Jonze directed it. I’ve been incredibly fortunate—I just get to work with brilliant people. But it’s funny because I was having this conversation with a friend . . . There was this period after I’m Still Here when I was getting a lot of big-money offers because they were crap things. I think a lot of people were like, “He’s fucked. He’s desperate.” These offers were, like, a lot of money—maybe not for other actors, but definitely for me. But I don’t want that power. I don’t want $20-million power.

MITCHELL: But isn’t that a way to get in there and change things—when you get that kind of money?

PHOENIX: Yeah, but you could also end up just being another motherfucker who gave up on their ideals. To get to that place where you’re making those movies? I just don’t know many people who have made it and kept their identity. I’ve never made $20 million. I’m scared. I don’t know if you gave me The Ring if I could carry it and bring it to Ozamorph, or whatever you call it. I think I’d put it on and test it out—especially if somebody was like, “It’ll be a crazy, wild time.” I’ll be like, “Yeah, I’ll try this bitch on.” I don’t know if I could take it back off. I don’t know that I’m strong enough. I’d like to think that I was strong enough . . . But I’m getting there.

ELVIS MITCHELL IS INTERVIEW‘S SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT.