the worst person in the world

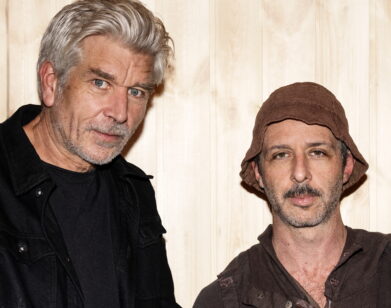

Joachim Trier’s Cinema of Intimacy

Joachim Trier is not particularly concerned with plot. Instead, the Norwegian-born filmmaker sees himself as more of an anthropologist, motivated by exploring human behavior and identity, and capturing authentic interactions between real people. For Trier, this fascination began in adolescence, when he filmed his friends’ attempts at death-defying and technically-complex skate tricks. That “openness,” as he describes it, still fuels the 47-year-old filmmaker, and it’s especially palpable in his latest film, The Worst Person in the World. The movie, organized as twelve chapters in the life of Julie (Renate Reinsve, who won the Best Actress award at Cannes for her performance), a woman navigating grief, insecurity, and perils of love lost and found as she passes from her 20s into her 30s. Trier sat down with us to discuss his new film, the challenges of creating textured characters, and the reason why he never watches his own movies.

———

JACKSON WALD: Following the release of Thelma, when did the idea to make a romantic comedy, and this movie in particular, begin to develop?

JOACHIM TRIER: A few years ago, several things happened at once. One was that I wanted to make a film which had a sense of freedom. The early works I’ve done, Reprise and Oslo, August 31, were films that were free in the sense that they reflected the reality of how the people I know behave and live. [I wanted to create] something that presented bigger themes through a more realistic lens of everyday Oslo. Thelma was a great experience, but it had 200 CGI shots that were very meticulous and quite challenging. I wanted to try something more chaotic and human and messy. Also, I wanted to do something with Renate Reinsve, who had a minor part in Oslo, August 31. I was also curious about the generational love story. A guy in his 40s and a girl turning 30, how do their perspectives on time and life compare?

WALD: What was it about Renate that fit so perfectly in the role of Julie?

TRIER: I was lucky to know what everyone knows now, which is that Renate Reinsve is amazing. I absolutely knew Julie was going to be her. I come from skateboarding. I used to film my friends every day doing something new or crazy —jumping down a big set of staircases, working on it for hours to get it right. In a strange way, with Renate and Anders [Danielsen Lie] and Herbert [Nordrum], I’m still trying to gather material. We always have a plan and a set script, but on the day of shooting, we try to maintain that openness. Renate is someone who plays into that. She prepares very intellectually, but on the day, she lets go, and that brings me back to my skater roots.

WALD: Some of my favorite scenes are where it’s just the viewer and Julie. She’s silent, and her facial expressions and body language are doing the talking. Could you tell me about the process of filming those scenes, and writing that into the script?

TRIER: It’s a process of creating a cinema of intimacy. I’m not particularly concerned with plot. My primary interest is human behavior and a sense of identification with the character who is struggling with something internal, getting inside the character’s ambivalence and complex, psychological issues. What is Julie going to do with her time? Her life? What’s her purpose? Who’s she going to be with romantically? Renate found a lot of that in herself—her version of loneliness, her version of insecurity and vulnerability. My job is to put a framework around her so she knows I’ll catch her, and that I won’t take that responsibility lightly when she comes on set. We call it, in Norwegian, “state-of-mind acting.” You’ve got to be immersed in the emotion, and then you can play with it. That’s the art of performance, and my job is to catch that on camera.

WALD: The movie centers around the life of a woman in her late 20s and early 30s. As a man approaching 50, how do you write a coming-of-age story from that perspective?

TRIER: It’s a very good question. My writing partner, Eskil Vogt, and I approach it by immersing ourselves like actors in the characters, and we jump between them to try to find everyone’s reason. I’m not interested in judging. I’m interested in how we can externalize the struggle inside the character. The question of gender comes up a lot these days, which is important. But I think the most important question is, “How can one be truthful to a character as a writer, regardless of our differences?” Those of us who have chosen to make movies have to transcend our personal identity to be able to convey stories of a broader spectrum of human beings. That, to me, is the goal—to open up to characters that you identify with, even though they might be a different age or different gender. I don’t take that lightly. I had to find the Julie in me.

WALD: Writing what you know, but not writing about yourself. That’s kind of a tricky balance.

TRIER: You have to write with curiosity and openness. Be aware that everyone who creates art has blind spots, but you attempt it with genuine respect and curiosity. I was talking to a friend of mine the other day, who’s also a filmmaker, about how difficult it is to describe what we actually do. You think you know what you’re doing, but it’s the moment you show it to other people that you realize what you’ve done. You’re kind of half-blind and half-intentional throughout the process. It’s like if someone asks you about your face. Actually, everyone else knows your face better than you do yourself. But it’s your face. Sometimes I feel like that about my work. I show the film and I think I have an idea of what it is, and people tell me it’s something different. I’m surprised sometimes, but mostly I’m grateful that they’ve enjoyed it, that they can say, “this touched me.” I’m like, “That’s probably also what I was trying to do.” But when your posters are up around town, and you’re the name on the poster, everyone assumes that you know exactly what you’re doing. Most creative people that I admire are quite unsure about what they’re doing. They’re searching while they’re creating.

WALD: When you rewatch your movies, do you ever see something that you didn’t see the first time?

TRIER: I haven’t gone back and watched my movies. Maybe I will when I get older, but at the moment I’m always looking for the next film. I do appreciate having conversations like this about what I have done, because a part of my brain is still learning about my craft. I’ll give you an example. I intended to create The Worst Person in the World in one climate, and then COVID happened, and people feeling lost and lonely became a common theme. When the film was finished, it was during this moment last summer when people were feeling hopeful that we would kick this awful thing. Now the film is being released, and people are sad again, because of Omicron. The waves of the world coincide with the film, month by month. It’s so radical. Ultimately, the film is trying to convey a sense of acceptance and hope that loss and despair will pass. There is a space for growth in those moments of feeling lost and lonely. It’s interesting to travel through a year with the movie and realize it has different effects at different stages. But these things are out of your control as a storyteller. You don’t quite know what the world’s gonna look like when you put your film out there.

WALD: You’ve mentioned your fascination with exploring reality. There are two moments in the movie—one involving a light switch, the other involving magic mushrooms—where there is a clear break from reality. How do you integrate those surreal scenes into a movie that digs into the real and the uncomfortable?

TRIER: In the five films I’ve made, I have moments that are more formally experimental. I always try to play around with form because I think we should push cinema to be more playful. In literature, early 20th century writers like Proust, Faulkner or Joyce pulled the craziest stunts, but they would still make sense in the narrative. In cinema, people are more cautious, but there are, of course, great filmmakers who’ve explored the vast possibilities. The almost musical sequence of the frozen-in-time scene, or a mushroom trip that allows us to enter Julie’s subconscious, gives us a broader perspective on her world and her imagination. The film is about someone who has difficulties negotiating the difference between the imagined and the real. A great quality in Julie is that she is very imaginative, and she always dreams of what’s next. She has great expectations, and I sympathize with that.