Jennifer Connelly, ClaudiaLlosa and the Art of Empathy

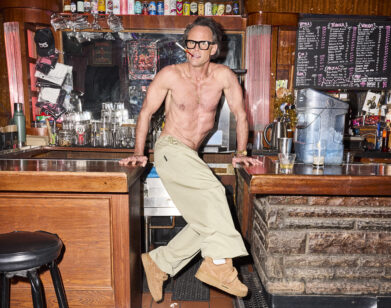

ABOVE: JENNIFER CONNELLY (LEFT) AND CLAUDIA LLOSA AT THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL, JANUARY, 2015. PHOTO BY KATIE FISCHER.

There are three characters at the center of Aloft, the first English language film from Peruvian director Claudia Llosa: Nana (Jennifer Connelly), a widowed mother of two sons-turned-healer and cult figure; Jannia (Mélanie Laurent), a French documentary filmmaker; and Ivan (Cillian Murphy), a reclusive falconer and Nana’s estranged son. Though they shouldn’t have much in common, the three share an intangible sadness that can only be resolved through one another.

Beautifully shot in snowy Canada, Aloft is a lyrical meditation on pain that comes with human fragility and human error. “There’s a lot of room for grey area in terms of the choices that the characters make,” explains Jennifer Connelly at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. “They all do things that are morally ambiguous, and I really appreciated that.”

EMMA BROWN: I wanted to talk about the character of Nana. I feel like she’s sort of the opposite of “charity begins at home.” She leaves her family and serves the greater good, but it causes them great pain.

CLAUDIA LLOSA: I love the way people relate to the film and find their own way of understanding it. For me, she’s just the best mother she can be and she has this unconditional love for her kids but there’s something super dramatic about the way she lost one of her kids. That is really important in the decisions that she makes after. It’s very complicated. I feel like she really has this ability of empathy with the kids and with others, but at one point she decides to go and find another way of surviving.

JENNIFER CONNELLY: She has an immense amount of love for both of her boys. I think the ways that she expresses it are a bit unfamiliar to a lot of us, just in terms of her personality. But you can see her love in her gestures, in her fight for her son. There are a lot of years in between and you don’t see what happens and you don’t know exactly the story—if there was anything else that went on between her and Ivan. What I like about the movie is that Claudia reserves judgment and considers what it might be like to have lost a child under those circumstances. In the end, those two characters are able to forgive one another, and to an extent, themselves, and they both have their own complicated road to learning how to live again after that tragedy. I think different people will see her character in different way—some people will be outraged that a woman would leave her child, and they don’t want to consider extenuating circumstances. Some people may look at it and say “Wow, what a horrific thing to experience, the loss of a child. And those of us who haven’t experienced it, how can we possibly say what might happen and how it might change us?” Certainly there are absent mothers all over the place who disappear into drugs, who disappear into alcohol, who disappear into their work. Then there are some people who will say, “Well, maybe she found that she wasn’t able to give him what he wanted then and she had to find a way to give it to him. In the meantime, she seemed to be giving this love to other people and other people took comfort in her presence.” Ultimately, they do repair—not with her own self, but with the love of another woman that he’s found, she’s able to somehow give him what he needs and complete that circle.

BROWN: Clearly Nana’s a very loving person and wants to help people and cares about people, but you can understand her son’s anger towards her.

CONNELLY: I think that by the end they had each come to a place of thawing—something again was coursing through them, something that had been arrested for each of them.

LLOSA: We have this tendency, this urge, to control and to understand and to possess the truth of things. But there are moments in life where, independent of the circumstances, we allow ourselves to react irrationally. I think what is beautiful about the path of these two characters is that even if they don’t find the words to understand—and they are not justifying [anything]—they are able to forgive themselves. Forgiving the understandable is one thing, but there’s something else about being able to really forgive the thing that you cannot understand. There’s a reminiscence of justification in forgiveness that I don’t believe in, personally. I believe that we can find a way to forgive each other without justification but with empathy and understanding

CONNELLY: This is without saying that they reflect our point of view, or that they represent our feelings. Like, I’m freaked out because I can’t get home to New York tomorrow and see my three-year-old daughter, and I’ve only ever left her twice. My maternal instincts are very different; I am different as a mother. But I can see her point of view.

BROWN: Do you think that you take away something from every character that you play? Is that the best outcome?

CONNELLY: It never feels so packaged in a very tidy way, like, “this is the little kernel of truth I’ve taken away.” They are always really interesting experiences, maybe just in the way you collaborate with someone—just something in that time that you share together—or something that you can find working on a particular character.

BROWN: At the end of the film, there are some obvious ways in which Nana has physically changed. One thing that stood out to me was the tattoos she had on her fingers.

LLOSA: It was very nice the way we talked about how Nana was supposed to be years later. We wanted to understand her skin, her hair, how she was. She’s a very physical woman, she spent so much time outside in the winter, in the nature, so she has a very specific way of aging. I don’t want to reveal exactly what it was, but it was kind of the idea that there’s a lot of things that this woman experiences over those years and we wanted to create the sense of little clues that Ivan can read. For me, these references were really clear in philosophers and artists.

CONNELLY: We did a lot of references with a lot of artists and musicians and things like that. With the tattoos, I had a little tattoo pen—basically a sharpie. I would just play around making designs and tried to figure out what I wanted to do and what they would mean and where they were.

BROWN: Claudia, what made you want to make a film in English?

LLOSA: I don’t mind working in another language if it really serves the story and in this case it was like that. It’s a little bit difficult sometimes to find the right words, but I do work on my script so I have the time—I usually find a way to express myself. It brings something new about yourself, you become something different—your humor, everything.

BROWN: Could this story have taken place in another setting?

LLOSA: The story started very clearly in my mind. In the snow, at a very early age you’re exposed to the vulnerability of life in a very dramatic way. I knew the environment was a character itself. When I started researching, I thought about going up in North Europe, but then there was something about the landscapes in that area particularly, near Winnipeg and the border between Canada and the U.S. The sun is really close. You could feel the cold but also it’s kind of warm at the same time. It’s a difficult, beautiful strange feeling that I wanted to be sure I had in the film—not completely in the cold weather and with this feeling of the light always present.

BROWN: Do you generally begin a film with such a clear image?

LLOSA: It’s a very long, organic process—this story started with four brothers. Some things were clear; I really wanted to explore the vulnerability of love, of affection, of very tight strength bonds and how fragile we are and how desperately difficult it is to accept that vulnerability. It’s not comfortable.

ALOFT IS CURRENTLY SCREENING AT THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL IN PARK CITY, UTAH.

For more from the Sundance Film Festival 2015, click here.