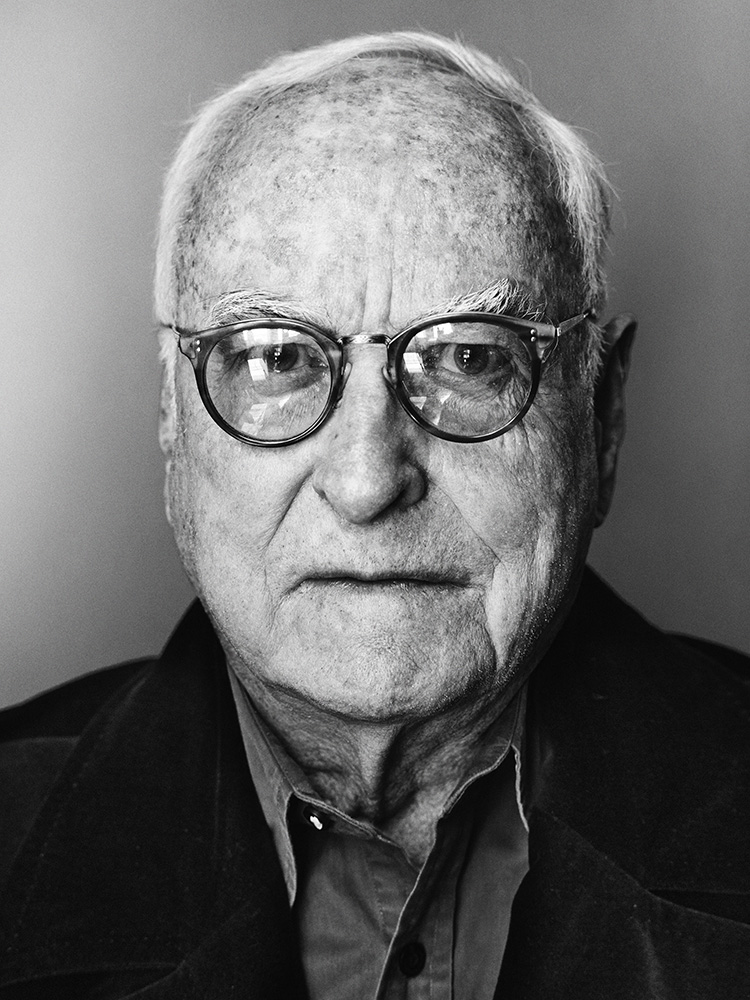

James Ivory

On a mantle in James Ivory’s country house in upstate New York sits a framed photo of actress Maggie Smith, dressed up in 1920s finery, from the set of Ivory’s 1981 film Quartet. By the fireplace in an adjoining room is a modernist wood chair that was used for Anthony Hopkins’s turn as Pablo Picasso in Ivory’s 1996 biopic. These and other treasures are so subtly incorporated into the elegant, relaxed, ever- so-slightly-aristocratic décor that the first description that came to mind, not at all ironically, was that it felt “very Merchant Ivory.” That designation, which hitches the director’s last name to his partner in life and cinema, the late Ismail Merchant, has come to stand for an entire sensibility, one of beauty, culture, and refinement, and also one of wild intellect and rough passions rumbling underneath the petticoats of propriety. Ivory isn’t the only director whose name summons a particular cinematic style, although that kind of recognition is usually reserved for auteurs whose body of work is held together by posturing and ego. Merchant and Ivory, on the other hand, consistently created new and distinct universes in their 25 films together as producer and director. Each one is its own island running on its own set of codes, where every detail—from the script to the casting to the costumes to the painterly backdrops—is so carefully tended that the audience has no choice but to be overwhelmed by it.

Ivory’s first film with Merchant (and their longtime screenwriter, the late Ruth Prawer Jhabvala) was the 1963 comedy of manners The Householder—which led to a spree of Indian-centric films including the critically acclaimed Shakespeare Wallah (1965). After delving into American period pieces tailored from the work of Henry James (The Europeans, 1979; The Bostonians, 1984), Merchant Ivory created two films that would permanently solidify their outsider status as cinematic masters of high literary form: adaptations of the E.M. Forster novels A Room With a View (1986) and Maurice (1987), which not only swam against the crass commercial tide of blockbuster Hollywood, but also managed to provoke, astonish, and seduce. In the case of Maurice, perhaps because the film was so disarmingly refined and the quality of the acting and directing so strong, its central gay love story was allowed in the front door rather than treated as a dirty secret to be sneaked in through the back. For all of their splendor, these particular Merchant Ivory productions are undeniably political, ushering their audiences forward socially even as they showed us worlds of a seemingly primmer past. Merchant Ivory found success decade after decade, and they did so by never drifting safely in their established niche. Ivory went from directing an ode to downtown bohemia (1989’s Slaves of New York) to an exquisite pre- and post-WWII British drama (1993’s The Remains of the Day) and, between those two unlikely partners, happened to make one of the finest films of the 20th century, Howards End (1992). Ivory’s latest project sees him taking a break from the director’s chair to serve as co-producer and screenwriter on Luca Guadagnino’s gorgeous upcoming gay love story Call Me by Your Name. At age 88, Ivory knows a thing or two about bringing literary passions to life.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: Your house is so beautiful. It reminds me a little of the one in Howards End.

JAMES IVORY: Maybe a little bit. The house where we shot the film in England is much older. This house was built around 1805. When I found it in 1975, it had been divided up into seven apartments, which I didn’t mind because the tenants helped pay off the mortgage over the years. But it sold me then and there as soon as I saw it. Slowly, over time, the tenants moved. It became fully mine in 2010.

BOLLEN: Do you do work up here? Or is this your refuge from Manhattan and the film world?

IVORY: Our editing room was here from the time we made A Room With a View onward. We turned the upstairs of the barn into an editing room. And we did every film right up to The City of Your Final Destination [2010] in that editing room with only one or two exceptions. It was actually a miserable place to be in the depths of winter. It just got to be too much, and I remember deciding to go back to New York to work on Surviving Picasso.

BOLLEN: The winters up here can be bleak.

IVORY: I know about that. There’s a cabin in Oregon I go to, which belonged to my parents. It’s never been winterized. It’s not a place you want to be after the first of October or before the first of June. I go for about three weeks every summer. In fact, that’s where I watch a lot of movies. I collect them throughout the year and bring them to the Oregon cabin.

BOLLEN: Old films or new?

IVORY: Both. For example, I just bought Sunset Boulevard and All About Eve. I remember seeing those when I was a college student and arguing with my friends about which was the greater film—which one was better in terms of pure cinema and which one was more “Hollywood.” We were divided.

BOLLEN: Which side were you on?

IVORY: Sunset Boulevard.

BOLLEN: Oh, my guess was All About Eve.

IVORY: Well, I might reverse it now. I will let you know after I watch them in Oregon.

BOLLEN: You were born in California and grew up a child of the West Coast. Yet I would never describe your aesthetic or approach as Californian—and certainly not Hollywood. Was it a conscious decision to build a career outside of the industry?

IVORY: The conscious decision, early on, was that I was going to live in New York. That was it. I went to Europe in ’52 or ’53, and when I came back, I stopped in New York. I remember looking out of a window on a glorious October morning and there was New York. And I thought, “I’m coming here. This is for me.”

BOLLEN: The New York birdcall. Did you move there right then?

IVORY: I did in 1958, after I’d started making documentaries.

BOLLEN: Your first documentary was about Venice, which, like New York, is a city that calls certain people.

IVORY: I go all the time. I suppose it’s the place I love most in the world. When I went to Europe for the first time, I went to Paris and then to Venice. So after Paris, Venice was my first great European city, and it just blew me away. The reason I made that documentary as my thesis at USC film school was to have an excuse to go back to Venice. [laughs]

BOLLEN: Was your plan always to be a filmmaker?

IVORY: No, I thought I was going to be a set designer. That’s why I went to architecture school. I mean, I hardly knew how movies were made. The cult of the director and all that stuff didn’t exist then. That didn’t come until the 1960s French new wave. I scarcely knew what a director even did. I knew what actors did and I could imagine what a screenwriter would do, but I didn’t understand the whole setup, really, until I made my first feature. And that first feature was with Ismail Merchant.

BOLLEN: Then how did you end up making a documentary for your thesis?

IVORY: I had to write one for the program, and I thought, “Wouldn’t it be better if I just made a film?” I proposed it, and my teachers said, “Why not?” They weren’t that enthusiastic. They didn’t say, “Wonderful idea, Jim! Fabulous!” They weren’t going to fund it. My father paid for it. I thought it would be a kind of art film set in Venice, telling the history of Venice through paintings.

BOLLEN: With Venice: Theme and Variations [1957], you were on your way to becoming a recognized documentarian.

IVORY: It was a film about the art, but it was also about the everyday city itself: the sunsets and gondolas and all the stuff that we know and I suppose is a big cliché. But it wasn’t to me. It was all glorious and new and something I wanted to get down on film. It had no sound so I had to create a soundtrack when I got back to school. After I finished it, they made me write a thesis anyway. [laughs]

BOLLEN: Then you made a second art film on Indian miniature paintings, which was also a critical success.

IVORY: I saw this collection of Indian miniature paintings in the gallery of a dealer in San Francisco. I was so captivated by them. I thought, “Gosh, I’ll make a movie about this!” It’s the arrogance of youth. Again, I knew nothing. Just like when I went to Venice, I didn’t know much about Venetian paintings. But at that moment, Indian music was beginning to be heard in this country—artists like Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Khan. And there was beginning to be an awareness of India as a great sort of fabulous, distant land. And so, again, my father put up the money. The film was called The Sword and the Flute [1959], and, like Venice, it was put on The New York Times best of the year list. It was because of the success of the first two documentaries that the Asia Society in New York got the idea to send me to Delhi to do a documentary about the city [The Delhi Way, 1964].

BOLLEN: Was that initial trip to India love at first sight?

IVORY: Oh, definitely. I adored it. And all the terrible things that can happen to people in India if they’re not careful didn’t really happen to me. I didn’t get sick or end up in some dreadful massacre. I just loved it and I quickly made a lot of friends. I met Satyajit Ray, who would later become extremely helpful to us.

BOLLEN: Is Delhi where you first met Ismail?

IVORY: No, there was a screening of The Sword and the Flute at the Indian consulate in New York. He knew the actor Saeed Jaffrey, who had done the narration for it, so he went to see it. Ismail came up to me afterward, and we became acquainted. Ismail had already been living in Los Angeles and produced a dance film [The Creation of Woman, 1960] that he took out to California and, lo and behold, got it nominated for an Oscar. He was only 23 or 24.

BOLLEN: So Ismail had the film bug early on?

IVORY: From the time he was a teenager, he wanted to get into film. He saw Satyajit Ray’s films and that changed everything for him. And he loved American movies, as they do in India. Anyway, I returned to India to shoot more footage, and Ismail had gone back home with all kinds of plans to make his own films in India. So we got together in India. He had planned to make a feature that didn’t work out. But he had read the novel The Householder by Ruth [Prawer Jhabvala]. It was Ismail’s idea to make it into a film because it was such a wonderful book. I read it and thought, “What do I know about middle-class Indian society?” But Ismail and Ruth knew everything about it. So I said okay. We also had Satyajit Ray’s crew because he wasn’t busy just then. So it sort of became a family thing.

BOLLEN: And thus began the Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala triumvirate that would last for more than 40 years. You made a series of terrific feature films set in India. Was there any pressure in those years to migrate to Los Angeles and join the ranks of lucrative American filmmaking?

IVORY: Well, my father did think I should get interested in television. But I had very little interest in television in those days, and it wasn’t something I wanted to do. I really never thought about going to work on big feature films in Hollywood. But when we made The Householder, Columbia Pictures bought it. Who would have ever imagined?

BOLLEN: Were they instantly receptive, or did you have to push to make that deal?

IVORY: Ismail was a person who could convince you of just about anything.

BOLLEN: Were any Indian or Bollywood films an influence on you?

IVORY: Not really. Now they’re very sophisticated, but back in those days they were quite crude. I’m sure it was in Ismail’s blood. Sometimes in our Western films, I feel, due to him, there’s an influence of Bollywood. Like a song sequence suddenly pops up.

BOLLEN: Slaves of New York is rather Bollywood—particularly with the impromptu Supremes drag performance on the street. Did you find any backlash in the 1960s to this California-born director taking on India as the canvas for his films?

IVORY: No, people liked them. The backlash came when we abandoned them and started making American movies. You know, “Why are they doing that? Those nice young men are making these wonderful Indian movies.” When we made Savages [1972], which was our first American film after four Indian features, we had the most devastating reviews you could imagine. It’s a surreal, nutty film, but it’s fun.

BOLLEN: It’s rare that filmmakers can have so many different periods—most get pinned to a certain genre, and no one will let them evolve.

IVORY: I think because we were living in New York-all three of us—we were always moving back and forth. We’d make a film in England and one in France and then one in India and one in New York. Our English films are spread across quite a long period—and during that time, we made a lot of non-English films, like Mr. & Mrs. Bridge [1990]. But everyone liked the English films so much that when we moved away from them, it was like when we moved away from our Indian films. After making A Room With a View and Maurice, and then doing Slaves of New York, people were just aghast.

BOLLEN: It’s too bad because Slaves of New York is one of the few films that perfectly captures the magic of SoHo and the East Village in the 1980s. It holds up so well. In fact, it’s almost mournful to watch it now, because that whole world you depicted of downtown Manhattan art bohemia is gone.

IVORY: It’s gone. And all the people who made the dream are gone. They probably went to Brooklyn. Or maybe they can’t even afford Brooklyn anymore.

BOLLEN: They’re certainly not in SoHo. Let’s talk about A Room With a View. When I told friends I was interviewing you, a lot of them confessed to me how much that film meant to them. They had memories of watching it on repeat as a kid. And I know for so many gay men, the nude swimming scene in that film and basically the entirety of Maurice had a huge effect on them when they were growing up. You just didn’t see male nudity onscreen in the 1980s unless it was accompanied by an even more naked woman. But those two films allowed for moments of an authentic gay sensibility to appear onscreen in highly respected features that couldn’t be written off as marginal. Were those films difficult to get made?

IVORY: A Room With a View was rather easy to get made except that … well, there’s a backstory: Satyajit Ray wanted to make a film of Forster’s A Passage to India. He even went to visit Forster when Forster was still alive and brought his films to show him. Forster would never allow any of his novels to be made into films. But Ray thought he could persuade him to let him do A Passage to India. Ray said that Forster liked the films but still said no. Then Forster died and Ray kind of changed his mind about the book. Anyway, we got a message from Forster’s estate at King’s College in Cambridge inviting us to come up and have lunch. They wanted to talk to Ismail and me. We knew they were probably going to offer us A Passage to India. We had just done Heat and Dust [1983], which was a big success. But we had already decided that we wanted to do A Room With a View. So we went and had a wonderful lunch at King’s College, and they did in time offer us the rights to A Passage to India.

BOLLEN: Why didn’t you want to do it?

IVORY: Because we had already done Raj-period India with Heat and Dust, and by that time, I wanted to go back to Italy to make a movie. I hadn’t been there for 20 years. So we asked if we could instead have the rights to A Room With a View, and their faces fell. [Bollen laughs] It was like, “What? That little novel? Why would you want to do that if you could do A Passage to India?” But we were decisive, and they said all right.

BOLLEN: And you got to go to Florence.

IVORY: Right. I didn’t know Florence at all, but I came to know it and love it. After the success of A Room With a View, we went back to them to ask about Maurice and again their jaws dropped. I don’t think it was the issue of homosexuality. They didn’t care so much. They saw it as an inferior novel in terms of its literary merit. Maybe they’re right and maybe they’re wrong, I don’t know. But I went back and read all of Forster’s novels and thought Maurice would make a really good movie. It’s all about not being truthful to yourself. That’s the message of both of those books. So we asked and they finally gave their permission.

BOLLEN: How did you handle the filming of the nude scenes in those films? Did the actors have to be talked into it?

IVORY: They didn’t give a damn. There’s also a nude scene in Quartet. And we couldn’t get a French actor who would disrobe. The girls playing in the porno-shoot scene also didn’t want to disrobe completely because it was a movie made with foreign money for 20th Century Fox with foreign movie stars. And for some reason, no French actor wanted to appear naked in such a movie. Luckily, there was an Englishman we knew who said, “Yeah, I’ll do it.” So he’s the one who took off all his clothes and also fights with the pornographer. That was our first real nude movie.

BOLLEN: Was there any outcry at all over the nudity in A Room With a View or Maurice?

IVORY: None! If we had showed big close-ups or something, there might have been an outcry. But we didn’t. They were just these guys running nude and no one cared. The same with Maurice. But today people would care.

BOLLEN: That’s the thing. You watch Call Me by Your Name, and you realize that there aren’t that many movies between Maurice and this one that have dealt so intimately and openly with gay men. That’s a 30-year gap, and maybe it feels more of a shock onscreen now than it would have in 1987.

IVORY: That’s true. And I just read an article about how young American males feel uncomfortable appearing naked in front of each other in locker rooms. That was never the case when I was young. We were naked in the Army all the time. And neither actor in Call Me by Your Name appears fully naked. I think there might have been clauses in their contracts that ensured there would be no nudity. When I wrote the script, there was plenty of nudity. But the English just had none of the same squeamishness about it.

BOLLEN: Did any of the actors—or the actors’ agents—in Maurice have concerns about being typecast for playing gay in a film?

IVORY: Not at all. And the film came out at the height of the AIDS epidemic. Perhaps because of that, people didn’t dare to be negative about the subject matter. Actually, there was something that happened in England, which was strange. The press for Maurice was very good in America. It was less good in London. It was as if the critics had backed off from it and didn’t want to compromise themselves. Now the London film critics at that time were almost to a man, gay. But they backed off and did not support it like they might have. Whereas, in America, everyone supported it. Well, not Pauline Kael, of course.

BOLLEN: Did you receive a lot of letters from gay men after Maurice came out?

IVORY: Not so many at the time, but lots have said since what that film meant to them. I had a guy in New York who recognized me and jumped off a bus to tell me how I changed his life. Isn’t that something?

BOLLEN: Yes, and deserved. It’s a rare film.

IVORY: Well, it’s one of the very rare gay films, if you want to call it that, which has a happy ending. If you think about Brokeback Mountain, which was such a terrific movie, it has this grim ending.

BOLLEN: And Call Me by Your Name also eschews that heavily negative dimension we come to expect with the subject.

IVORY: Yeah, there’s always a kind of sinister shadow somewhere, almost like the character is being made to pay for this aberration.

BOLLEN: What’s amazing about A Room With a View and Maurice is that you smuggled in these political and sexual messages under the banner of the staid literary classic. And really you were introducing the work of Forster and Henry James to a whole generation. When you work from a novel, do you feel the pressure to stay true to the author’s intentions?

IVORY: Why take up a writer and their story unless you are going to tell that story and are going to maintain the tone of voice of the writer? You have to. Otherwise, what’s the point? You should do something else. Of course, you have to make changes. You make cuts and drop whole characters. But I think the basic story has to be the same.

BOLLEN: Were you offered a lot of projects after the success of Howards End and The Remains of the Day?

IVORY: We were on the edges of Hollywood and, after those films, they really got interested in us. We could make a box-office movie for very little money, which all the critics were crazy about. And what was our secret? Well, it’s only good for so long, as all directors know who make a successful independent film. Let’s just see what happens with the people who made Moonlight. Hollywood wants to exploit you, which is fair enough because they’re offering you money you’ve never had before.

BOLLEN: Can you tell in advance what’s going to be a success?

IVORY: I always assume that nothing that I make is going to be a success, that everything I make is going to be a failure—not a failure but not some huge box- office success. If something is an artistic success, I’ll be happy, but I’ll maybe be the only person that’s happy with that apart from Ruth and Ismail. Most of our films have not been big box-office films.

BOLLEN: Over the years you’ve made so many incredible parts for women. And your female leads are legion: Vanessa Redgrave, Emma Thompson, Isabelle Adjani, Julie Christie, Bernadette Peters, Raquel Welch, Helena Bonham Carter, Maggie Smith, Lee Remick.

IVORY: They were good parts, and they might not have had such good parts if the screenwriter hadn’t been a woman. Ruth Jhabvala wrote so much fiction with very interesting heroines. And, of course, in terms of Forster, Margaret Schlegel [Thompson’s character in Howards End] is really him.

BOLLEN: Margaret Schlegel might be one of the best characters period. Emma Thompson is perfect. She and Helena Bonham Carter actually seem like they’ve been living together for years the way they finish each other’s sentences. You don’t see two actresses with that kind of believable connection very often on the screen.

IVORY: Well, both of them are very smart and have terrific senses of humor. And both of them are very English.

BOLLEN: Did you and Ismail work on the casting together?

IVORY: Yes. Sometimes Ismail would cast people and then tell me later. [Bollen laughs] He cast Maggie Smith in A Room With a View. She was appearing in a play in London, and he went backstage into her dressing room after the performance and handed her the script and said, “We want you for this.” We’d already worked with her, so she knew us.

BOLLEN: Have there been people you’ve wanted to work with that you haven’t had a chance to?

IVORY: There have been. Sometimes we’ve sent them a script, and then you meet them at a party years later and you find out they never received it. That happened with Mick Jagger. We wanted him for The Guru [1969] before we offered it to Michael York.

BOLLEN: Mick Jagger really would have changed that movie.

IVORY: Yes. He’s unique. And he came to dinner one time when we were in Cannes with The Golden Bowl [in 2000]. I asked him if he’d ever gotten that script, and he said no. He would have been wonderful for that role. And he was doing movies then.

BOLLEN: André Aciman published Call Me by Your Name in 2007. Did his novel speak to you right away as a possible film?

IVORY: When I first read it, I was very impressed. At some point, a producer and an agent wanted to make it and asked if I’d be executive producer on it. I said sure. Eventually, Luca Guadagnino came on board. At one point, there was a discussion that we’d co-direct the film. I said yes, but I wanted to write the screenplay. I wanted to construct the script myself, and did so on spec, and everyone was happy with the result. More time went by and they were still trying to raise the money. Eventually, they decided it was best to have one director on board. Some of the details were changed. The script was originally written to take place by the Italian seaside in Sicily, but we ended up making it in Northern Italy by Lago di Garda and along a branch of the Po. But what really drew me in was that I liked the character of Elio very much.

BOLLEN: Elio is so intelligent and precocious without being irritating. It’s unusual to see a boy in contemporary cinema growing up in such a bastion of high culture and not have him rebel against it. Elio is such a positive product of his family.

IVORY: One of the challenges in writing the script was that I had to find something concrete for the professor to do. In the book he is some kind of classics scholar. But I thought it would be interesting to make him into something of an art historian and archaeologist whose background was the classical world. It’s always difficult when someone is supposed to be an intellectual. What do they do? You can’t just film them sitting around and thinking all day. And that’s what the business of the statues is all about.

BOLLEN: Are the statues a personal interest of yours? I often wonder how many of the details in your films are actually current James Ivory interests.

IVORY: Absolutely! Lately, I’ve discovered these Hellenistic bronzes. I’d never really thought about them much, but then there was this marvelous exhibition—many of them Roman, some of them Greek, all kinds of wonderful standing figures or heads or horses. It all suddenly became a passion of mine. I finally got to see that exhibition, which led to the idea of bringing up the statue in the film. The exhibition was full of statues found in the sea, some of them quite recently.

BOLLEN: People who have seen the film keep referring to two scenes. One is the peach sex scene—

IVORY: When I was doing the screenplay, people who read the book would go, “Oh god, what are you going to do about the peach scene?” I’d say, “I don’t know, but I’ll do something.” And finally I figured out that there was a way of doing it without being totally graphic. You can do it in a way where the audience gets it and accepts it.

BOLLEN: Then there’s this speech the father gives Elio at the end about accepting whatever his desires are in order to be true to himself. It’s a tearjerker.

IVORY: It’s pretty much taken from the book word for word. It’s a huge scene that gave weight to the part of the father. I had the feeling it was André Aciman really speaking there, that it was his personal philosophy.

BOLLEN: Did you speak with Aciman much when you wrote the script?

IVORY: No. I didn’t see much of him until the script was all done, actually. I sent it to him, and he liked it very much. The one thing he wanted changed was a scene I added of Elio’s parents talking to each other in bed. I have them sort of figuring out what is going on, and the mother is worried. But the father is not at all worried. Aciman didn’t think that should be in there. But it was an intimate scene between them, because at the end, the father reaches for the mother. He becomes worked up over this discussion of his son’s sexuality and he reaches for the mother. Which I thought was a neat idea.

BOLLEN: Are you working on any other film projects?

IVORY: I have this long-standing project—talk about working on something for years—which is Shakespeare’s Richard II. It has the most wonderful poetry in it, and it’s a very interesting story about a king. When he was young, he was very disagreeable and taxed everybody like mad. He was a tremendous clotheshorse. He kind of invented the whole idea of the spectacle of monarchy in England. But he rashly banishes his first cousin after the uncle dies and takes all of his possessions. So the son is not only angry but he’s been robbed. So he comes back to get his money and actually displaces Richard to become Henry IV. Richard is put in prison where he suddenly becomes a philosopher king and Henry becomes the villain. My friend Chris Terrio already wrote the script and Tom Hiddleston is going to play Richard. Damian Lewis is going to be Henry. Well, that’s the plan at least. We’ll have to see what happens with it. They better hurry up, because I’m not getting any younger.

BOLLEN: I hope you don’t mind this question, but I wanted to ask how it’s been to make films after Ismail passed away.

IVORY: I’ve only done one.

BOLLEN: Did his death change your relationship to film?

IVORY: Not really. We had already begun to set up The City of Your Final Destination. Ismail and I had gone to Argentina to find locations and Ruth had written the script, so we were working on it. But then we left that to go and make The White Countess [2005] in Shanghai. It was there, at the very end of shooting, that Ismail broke his ankle. We finished shooting and came back here and had to edit The White Countess. But Ismail somehow never really recovered. He was walking around, but there was a kind of depression that set in. And a very good friend of ours who was a wonderful producer in France, Humbert Balsan, killed himself. That just devastated Ismail. Then Ismail got another one of his bleeding ulcers, and unfortunately we were in London when that happened. Twice before it happened when we were in Paris, and both times the French knew exactly what to do. The English somehow failed and Ismail died.

BOLLEN: Was he in the hospital long?

IVORY: Three or four days. They thought he was going to be okay, but they did something wrong or they failed somewhere.

BOLLEN: That must have been so devastating.

IVORY: Yes, it was terrible. I could have plunged into real despair or depression, but I had to finish The White Countess, and that kept me going. It was not an easy film to finish. It was an expensive film, and there was an awful lot to do. And then I was more or less okay by the next year, and we went off to Argentina, and from then on, I’ve been involved in the Richard project. It’s the only thing I’ve really wanted to do since.

BOLLEN: Okay, my final question: We aren’t far from Edith Wharton’s estate in the Berkshires. You’ve done several films based on works by Henry James. Why no Wharton?

IVORY: If you have Henry James, why would you do Edith Wharton?

BOLLEN: Ha! Jamesians always say that. But I think you’d do an amazing The Custom of the Country.

IVORY: The Age of Innocence has the same story as James’s The Europeans, a film we did. There’s a foreign woman married to some abusive, dramatic husband who comes to live with her American cousins who think she’s just extraordinary, and there may or may not be some sort of romantic involvement with her. Eventually, in both stories, there isn’t one and the woman goes back to her abusive husband. I don’t think anyone has ever written about this, but it really is the same story all over again.

BOLLEN: One final comment. I rewatched The Remains of the Day last week and found the final scene between Emma Thompson and Anthony Hopkins so debilitatingly sad. I couldn’t get Emma Thompson’s weeping face out of my mind for days. It was so clear they would never see each other again, and was it worth it to be reminded of what you didn’t have?

IVORY: There’s a funny story about that scene. The story goes that the head of Columbia Pictures, which made the film, was apparently watching it alone in the studio, and when that moment happened with their hands pulling apart, a scene everyone loves, he supposedly jumped up and said, “There goes 50 billion dollars!” [laughs] Because it has an unhappy ending.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS INTERVIEW’S EDITOR AT LARGE. HIS THIRD NOVEL, THE DESTROYERS, IS OUT NEXT MONTH.