Dario Argento on Turning a Lifetime of Blood, Blades, and Pulp into High Art

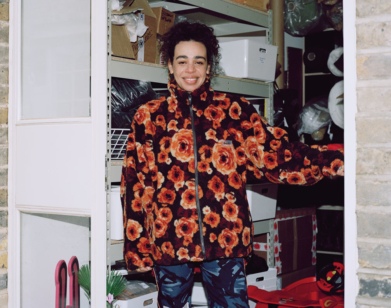

Dario Argento photographed by Benjamin Barron and Jeannette Montgomery Barron.

Early in Dario Argento’s first feature film, 1970’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, a handsome American writer strolling around Rome at night stumbles upon a murder that is already underway. The writer, played by Tony Musante, rushes to save the red-haired beauty struggling to fight off a shadowy, knife-wielding assailant inside an overly lit art gallery. The writer makes it into the vestibule of the windowed gallery space but can’t open the inner door. When the assailant locks the outer door, he is stuck between glass panes, the bleeding woman begging for help on one side and the freedom of the Roman night on the other. Our protagonist is literally and figuratively caught between frames, an unwilling, impotent, but enthralled eyewitness to a brutal and beautiful crime.

It’s little wonder that the upstart director chose a modern art gallery as the setting for his first cinematic stabbing. The pulpy Italian mystery-thriller genre of giallo had already been well under way in both literature and film (particularly with the lurid Italian director Mario Bava) by the time Argento began filming his first bloodbath in the late 1960s. And yet, with his first cinematic foray, Argento instantly elevated giallo into an art form. Horror was never the same again. The director is often referred to as the Italian Alfred Hitchcock, and while both auteurs were skillful at building pressure-cookers for plots, Argento developed a trademark style, sophistication, and perversity all his own. In film after film — The Cat o’ Nine Tails, Deep Red, and Tenebre among his very best — he employed the familiar trope of a maniac on the loose to build delicious, glamorous, vivid, and vicious jigsaw puzzles, with plenty of blood, eerie electronic music, whispering psychopaths, children’s nursery rhymes, vertiginous camera angles, odd animal cameos, and, Argento’s particular forte, over-the-top baroque deaths. The whodunnit riddle was never the point. Argento was making murder and mayhem into something far stranger: a seductive deep dive into our dark psychologies, with all the attendant political and sexual upheaval of the time.

As the 1970s wore on, Argento began to move from the straightforward, realist thriller to more supernatural fare. Films such as Suspiria (1977) and Phenomena (1985) explored covens and psychic powers, subjects that perfectly synched with the director’s surreal, dreamlike handling of camerawork, lighting, and trippy soundtracks. Those films also arguably created a feminist crook to the horror genre, a meaningful counterpoint to the exploitative female-as-victim cliché that had become the norm of American horror.

Today, at the age of 78 and living in Rome — and with roughly 25 director credits under his belt — Argento is the king of the dark. With the advent of more artistic and intellectually astute horror films coming out in the United States in recent years, it seems as if Hollywood has finally taken a few cues from the Italian master. Interview spoke to Argento about what scares him, how to capture those tricky death scenes, and the ritualistic nature of horror.

———

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You come from a family who worked in film — your mother was a photographer and your father a producer. Movies must have been a part of your life from an early age. Which films first sparked your interest?

DARIO ARGENTO: I had very eclectic taste as a kid. I loved dramas and adventure movies, crime and westerns. Then I discovered horror cinema, and it’s been stuck in my mind ever since. The images, scenes, and actors — that whole world has been stamped on my mind like a tattoo.

BOLLEN: I’m sure it was similar in Italy as it’s been in America: Horror didn’t share the same reverence or prestige as other genres.

ARGENTO: I was very fond of horror and I remember those films not being respected by my family or professors. I remember when a new Hitchcock movie — which I loved — was released, the critics underplayed it, calling it a “commercial” movie. I felt bad for Hitchcock and for those who, like me, felt part of this weird, alien clan.

BOLLEN: Edgar Allan Poe was a big influence on you as well, correct? And, in fact, before you were a director, you spent years as a writer and journalist. It’s probably no coincidence that in many of your early films, the protagonist is a writer.

ARGENTO: Discovering Edgar Allan Poe was my light in the darkness. His stories were so far from the routine of my everyday life that I eventually took him as a model or mentor. And, yes, all the years spent writing tales and magazine articles led me into the world that I had later made mine: cinema.

BOLLEN: I was trying to picture a typical Dario Argento mood board for each of your films. Where does the initial idea begin? How do you start building each haunting new world?

ARGENTO: My films are always brought to life from an idea, a coincidence, or a dreamlike magic. An ephemeral moment that settles in my mind and starts to bloom. The plot slowly appears before my eyes, and there’s nothing left but to write it. I actually do use a mood board. And location scouting is essential to the realization of the film. I’m inspired by architecture — the beauty of certain neighborhoods, the mystery in odd buildings, or streets that suggest psychoanalytic theories. I only choose my actors after I write the script.

Dario Argento on the set of Opera, 1987.

BOLLEN: What part do colors play in this world?

ARGENTO: Colors are fundamental instruments to give a tone, and soul, to the film.

BOLLEN: Giallo as a literary and cinematic genre was already in full swing in Italy by the time you made your first film. And yet, I would argue that you perfected it as an art form on that very first contribution, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage. What was it about giallo that enticed you?

ARGENTO: Giallo has always fascinated me — whether Italian or international — because of its mysteries, enigmas, the charm of the forbidden, the impossible love stories, the sensational plot twists, and a not-too-linear storyline. In the 1960s, when I actually started dealing with cinema — first as a journalist, then as a screenwriter—giallo was of very little interest to intellectuals. My grandma, a truly conservative woman, didn’t allow me to read them, so I would sneak into the attic to do it in private.

BOLLEN: What is it that makes giallo so distinctly Italian?

ARGENTO: Giallo is a potpourri of references. There was a torrent of themes and thoughts that agglomerated into Italian giallo. For example, let’s not forget the fierceness of the killers, the constant presence of female characters and their importance to the plot (especially in my movies), the unreal and highly artistic settings. Moreover, there’s the Italian soul that marks the stories and characters — something coming from our past, our religion, and our superstitions.

BOLLEN: I can see a kind of Catholic baroque in the design of your films — so much attention to color and light. How do you achieve these stunning visual spectacles time and again? It’s almost like there’s some Argento film stock that’s super saturated.

ARGENTO: I think my films are stunning because they are the result of so much study behind my scenography and camera movements. Peculiar structures, travels into the unknown, enigmas, feral yet extravagant killings, long shots of violence reminiscent of Aztec rituals — it’s all connected to my idea of this world that I recount in my films.

BOLLEN: You might be the director who has killed the most characters in bizarre and original ways. There’s no quick murder by pistol for you, unless it’s a bullet through the eyehole of a door as in Opera. Often it’s hatchets, spikes, rats, elevators, glass shards, razor blades, falls through windows. How do you keep thinking of new ways to off people? And which ones have been your favorites?

ARGENTO: I’ve had hundreds of murders in my movies. They’re my specialty. I visualize them when I write and I just let my imagination go. As for the research process behind the killing strategy, I take into account the particular moment in the plot and the character’s psychology in the scene. Some death scenes have been more successful than others. I’d have to mention the ones in Profondo Rosso (Deep Red), Suspiria, Tenebre, and Opera.

BOLLEN: Is it tricky to get a good death scene from an actor? They often have to be screaming and twisting and spraying blood from several orifices.

ARGENTO: No, it wasn’t hard for me to have fun with the actors and their macabre deaths. Once they understand their part, the actor interprets it to his or her best, following my prompts. And then when I’m editing the film, it’s my job to find the right moment in the acting.

BOLLEN: How have the censors traditionally treated your films?

ARGENTO: I’ve fought against censorship in almost every country in which my movies have been released. Today, censorship has mostly been abolished, although, until recently, it has harassed me all the time. I actually don’t think it’s been the fault of the Catholic Church; it was more about bureaucracy and conservative laws.

BOLLEN: Outside of the death scenes, your camera work is also exceptionally inventive. We often see through multiple windows or rooms, moving in close or zooming high above the action. What do you recall being the trickiest shot to execute?

ARGENTO: The camera work is my brainchild, and it doesn’t take weeks or years. It’s more like thunder in my brain. It’s intuition. The use of a jib in Tenebre might have been the most complicated moment [one long continuous shot using a crane that peers through multiple windows in a house before a killer enters, considered a landmark technical achievement]. Also, the crow scene at the beginning of Opera was a tough one.

BOLLEN: What scares you?

ARGENTO: Horror movies rarely scare me. I’m more frightened by nightmares—which do leave me anxious and terrified. Walking through my house alone can get me scared depending on what’s going on in my mind. Sometimes I feel surrounded by presences. But I guess that’s just inside my head—in the obscure half.

BOLLEN: I know you have respect for the director John Carpenter, but what about all of the ’80s American slasher films? Your movies are often considered one of the inspirations for that popular wave of horror.

ARGENTO: I think my films and American slashers are two completely different genres. I deal with psychology and the subconscious; without those elements, my films wouldn’t make any sense. Teenage horror movies don’t have anything to do with that, and most of the time they’re pointless and childish.

BOLLEN: And yet, I’m sure you could have moved to Hollywood at any time in your career and made American films. You’ve remained committed to Italian cinema. Why have you never shot in Venice, a city that seems designed for an Argento production?

ARGENTO: I’ve thought about shooting in Venice at several points in my career. Practical and financial issues have always prevented every attempt. I’ve written a couple of short stories set in Venice, and writing is so much easier because my creativity is not bound to political matters or complex operations. Shooting in Venice can be really problematic because of its bridges, canals, and the sea.

BOLLEN: There’s been a recent rise in America of artistic or intelligent horror — I’m thinking of films like Get Out and Hereditary. What was your take on Luca Guadagnino’s recent remake of your film Suspiria?

ARGENTO: To me, the remake of Suspiria doesn’t look like a well-realized project. It lacks fear, music, tension, and scenic creativity. Films like Get Out and Hereditary have struck me for their beautiful photography, their plot, and their production.

BOLLEN: Before you had ever directed your own film, you co-wrote with Bernardo Bertolucci the script for Sergio Leone’s classic Once Upon a Time in the West. Did you learn any lessons from Leone about film? And is there any advice you’d give a filmmaker starting out?

ARGENTO: Leone taught me the crucial role of the camera itself in making a film — a decisive lesson to me. As advice for a young filmmaker, you should watch many movies, many times, look for your direction within yourself, and follow that path.

———

Translated from Italian by Federico Sargentone.