DIRECTOR

In 2006, Paramount Sued Chris Moukarbel. Now They’re Releasing His New Documentary.

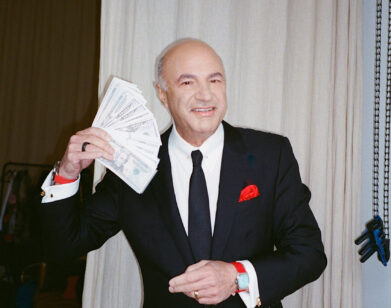

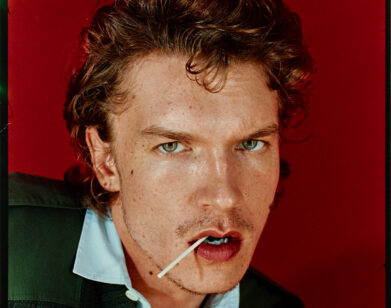

Chris Moukarbel’s life comprises an unexpected series of segments: born in Connecticut to Lebanese immigrants, he was a D.C. punk kid who joined the U.S. Army at seventeen, then left to come out and bartend at a popular gay bar, earning enough to buy a house at 24. This man does what he wants. As a student at Yale’s MFA program in sculpture in the mid-aughts, what he wanted was to get on an international stage by baiting Paramount into a lawsuit. Using a bootleg script from Oliver Stone’s 2006 feature World Trade Center, then not-yet-released, he made a video art piece that went viral. When the highly publicized lawsuit was settled, he could no longer distribute the art stunt, but by then he’d made his point. Over the years, Moukarbel successfully migrated to the commercial film world, directing a traditional popstar documentary (2017’s Gaga: Five Foot Two) and winning Best Narrative Feature at last year’s Tribeca Film Festival with a darkly satirical take on that very same genre (Cypher, starring rapper Tierra Whack). Now, Paramount+ is putting out his latest documentary, The Honey Trap, on December 6th. On election night, I called him up to discuss this full circle moment—as well as the war on Gaza, Arab representation in cinema, and the improbable story of Denis Cuspert, the subject of his new film.

———

THORA SIEMSEN: How are you holding up?

CHRIS MOUKARBEL: I’m okay overall. I’m grateful for a lot of things.

SIEMSEN: Shall we begin?

MOUKARBEL: Sure.

SIEMSEN: Okay. So, in 2006, you were sued by Paramount Pictures over a video art piece you made about 9/11 called World Trade Center 2006, which allegedly infringed on Oliver Stone’s copyright for his film, World Trade Center. That year, you told The New York Times, “I’m interested in memorial and the way Hollywood represents historical events. Through their access and budget, they’re able to affect a lot of people’s ideas about an event and also affect policy.”

MOUKARBEL: Yeah, I was pretty raw all the time. Being a young Arab American, especially those years after 9/11 and looking at the way the culture around me would represent Arabs and Muslims in such dehumanizing ways. I became obsessed with reading entertainment culture for hints as to what being Arab meant to the creative class here and ultimately, how I would be perceived as I moved through the world. My parents were working class Lebanese immigrants, and I sideways shuffled my way into Yale through the MFA art program. And at the time, I just felt like I had one shot to make some noise while there was that kind of attention on me. I was also at an age where I was testing the systems of power around me. For my senior thesis, I took a bootleg script that I found online for Oliver Stone’s upcoming movie about the World Trade Center and I built sets in my studio and shot all the scenes of the two Port Authority police officers that were pinned in the rubble of the elevator shaft and I released it on YouTube, which was pretty new at that point. It was really a way to preempt the release of the Paramount movie. I shot the script verbatim, and I remember telling my class that I was hoping to get sued, that that was the point of the piece. I woke up one morning about a month after I graduated and I was splashed all over the news. I was being sued by Paramount and Oliver Stone, and it became this major international news story that lived on for months, because there was a lot less going on online back then.

SIEMSEN: Would you speak to The New York Times now?

MOUKARBEL: Probably not. I just canceled my subscription after 15 years because of its transparently biased coverage of the genocide in Gaza.

SIEMSEN: Your new film, The Honey Trap, contends with the way Hollywood unfavorably represents Arabs and the entertainment industry as an arm of the military-industrial complex. It’s coming out on Paramount+. How is this full circle moment feeling for you?

MOUKARBEL: Well, it’s definitely a gag that this movie will be on Paramount. We started it with Showtime and then Paramount acquired them, so now it’s a Paramount movie. I kept waiting for them to watch it and kill it, but here we are. We slipped through. The movie that I just made is about Denis Cuspert, who’s a well-known Berlin rapper turned ISIS recruiter. He was targeted by the FBI, which set him up with an FBI translator online. Some say that she was a honey trap. But it’s documented that her objective was to lure him to arrest. She allegedly falls in love with him and runs off to Syria to marry him and join ISIS. So on the surface, it’s this crazy espionage story, but there are also all these layers where you sense that both of them are being used as bait by systems above them. I found an opportunity in the movie to unpack Arab and Muslim representation and entertainment culture, and we also shine a light on the long-standing circular relationship between the Hollywood studios and the Department of Defense. So many big commercial films get revision notes from the DoD Hollywood office, which radically changes stories all in service of fitting this U.S. military narrative. So many movies about the Middle East have actually passed through the approval gates.

SIEMSEN: Including, I learned, Marvel movies and Pitch Perfect 3.

MOUKARBEL: Right. It’s kind of crazy. You have obvious ones, like the war movies, but it’s also pop culture movies. It’s reality television. A lot of people just sense intuitively that that is happening, but you also don’t want to be paranoid, and this idea of propaganda and movies isn’t new. I just assumed it would be more war movies, so I was surprised that it was these rom-coms and even reality television, too.

SIEMSEN: What surprised you most on that front?

MOUKARBEL: Well, again, as an Arab person in this country, you are always analyzing the culture around you as a way to understand your own role and identity here. You become hyper-sensitive and aware of those types of films and the representation of your own identity, your own culture. In the tradition of war movies, you just go into it expecting that every year, a certain amount of movies are made that are supposed to take place in the Middle East. You have movies like American Sniper, which is one of the top grossing films of all time, and it’s just Bradley Cooper picking off Arab men from a distance. It’s become part of the accepted culture. Part of my recent film digs into all the blatant propaganda in the movies of the early 2000s. It was wild how much entertainment culture was running cover for America’s military adventures in the Middle East. And Arabs and Muslims were definitely maligned and dehumanized [in the process]. I think that’s why so many people can still accept seeing a genocide of Arab people because, in so many ways, Arabs are expected to die. That said, I’m also really blown away by the shift towards deep critique and real humanity that I see online.

SIEMSEN: What differences do you observe in our current political moment compared to 2006 and the jingoism of the Bush years?

MOUKARBEL: I think things have changed a lot. On the surface, things are the same in the sense that there is this sort of acceptance of Arab mortality, I guess, and that just comes through decades of conditioning. But I think that things are really different in the sense that young people are really activated online and they’re just culturally literate in ways that I felt like my peers weren’t when I was younger. I’m pretty impressed. There’s so many young people asking the right questions, nothing like that was happening in the Bush years. The narratives can’t be as easily controlled now because the media moves more laterally instead of just top-down.

SIEMSEN: Speaking of 2006, The Honey Trap references Jack Shaheen’s book Reel Bad Arabs, which was made into a movie that year. Which other texts do you recommend?

MOUKARBEL: There’s the obvious foundational reading like Edward Said’s Orientalism. But also, the conversation is moving so quickly now and there are so many people online that are doing incredible work. Our film interviews the academic Maytha Alhassen, and she talks a lot about the dynamic relationships between politics, pop culture, and public opinion.

SIEMSEN: How do you see this new documentary fitting into your filmography?

MOUKARBEL: It’s definitely a lot heavier. It’s more didactic, to be honest. A lot of my work tries to understand soft power. When I started making films, I just wanted to make things that were entertaining. I wanted to be cute and fun and not be perceived as an angry Arab with an axe to grind, although now that just feels like what I am. In certain ways, I’ve gotten really angry in the past year. But also, as I said, I really wanted to not be identified as somebody who made work about identity. I guess I felt like I deserved to do something else if I wanted to. So in a lot of ways, that was an objective of mine, to make work that could be entertaining and could be perceived as fun and lighthearted. But if I’m being honest with myself, a lot of the issues that I’m confronting now have probably always been there.

SIEMSEN: Do you remember the first depiction you saw of Arabs in a film?

MOUKARBEL: When I was a kid, I remember watching the Chuck Norris movie The Delta Force and seeing this sweaty, violent Arab terrorist just slapping blonde stewardesses, and it just made me feel embarrassed. The first Gulf War happened when I was a kid, and I remember sort of losing my father to it at the time. He was just really angry and would watch the news on a little TV. He set it up and slept in the living room 24/7. He was just watching the news and yelling at the TV.

SIEMSEN: Do you see contemporary representations of Arabs and Muslims as connected to the ongoing repression and criminalization of the Palestinian struggle?

MOUKARBEL: Yeah, but I think that the modes of representation are so different now. When it came from movies or TV, it felt so totemic because that was all anyone would see, and now there’s so many awesome Arab and Muslim people online—and not even being political, they’re just being cool. That would’ve probably made a huge difference for me growing up. I think the conversation around Palestinian liberation is really connected to what we see online now. People never imagined that they would be watching children being slaughtered while sitting on their couch, scrolling between fitness videos. It’s dystopian, and I don’t know when we’re fully going to realize the effect it’s having on us. But either way, I’m grateful there’s a light on it now.

SIEMSEN: What is the responsibility of a filmmaker at this moment?

MOUKARBEL: I can’t really prescribe a blanket responsibility, because there’s so many different types of stories to tell. A lot of them are outside of my personal world. I’m just happy for people to keep making movies, and I’d like to stay in the mix myself.

SIEMSEN: Do you have anything lined up?

MOUKARBEL: I’m trying to develop a narrative film, actually, and I guess I can’t speak to it in too much detail because it’s so early, but I can maybe say that it’s something that I read that I thought was interesting. I read a book called The Stowaway, and I’ve been talking to the author about it. It’s a true story. It took place in the mid-90s, and it’s about two Romanian stowaways who were thrown overboard as they made themselves seen after they had stowed away, I think, in the hopes that they would just be put to work. But a really deranged captain and his officers decided to basically put them in a makeshift raft with some barrels tied together and threw them overboard. It was a pretty shocking event at the time. But the story that I’m interested in, I think, is the story of the deckhands and their involvement and them having to process what they had been complicit in.

SIEMSEN: Wow. Keep me posted about that.

MOUKARBEL: Yeah, for sure.

SIEMSEN: Is there anything else you want to use this opportunity to say?

MOUKARBEL: I don’t know. Honestly, that was a lot for me. It was very personal, and I really appreciate you giving me the chance to talk about my own work like this. It’s not something that I’ve done. I’ve talked about individual projects. Over the years, I’ll do press for a movie or whatever, but it’s very rare. I can’t even remember a time where I just spoke more holistically about what I’ve made in the past and what it means to me, how it’s all the amalgam of who I am. So that was very cool.