ICON

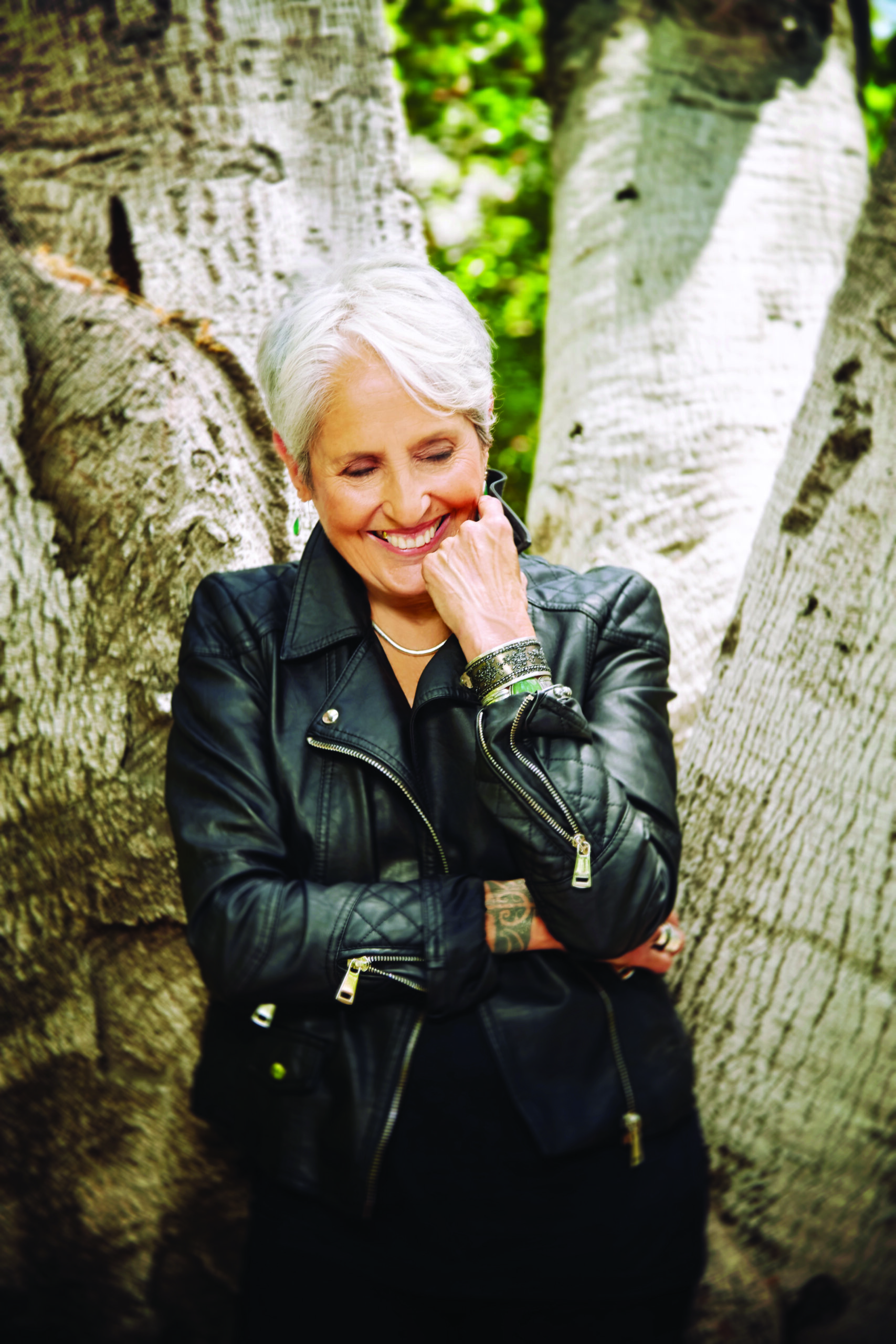

“I Wanted To Be You”: Joan Baez, in Conversation with Jane Fonda

When Jane Fonda got on Zoom to interview Joan Baez earlier this month, she opened with a confession. In her twenties, Fonda told Baez, “I was totally obsessed with you.” In the summer of 1967, while Fonda was filming Barbarella in Rome, Baez strolled into the house Fonda and her then husband Roger Vadim were renting. “I was making gazpacho and you came in,” the actor recalls. “I was just gobsmacked.” Baez, the ethereal singer-songwriter and unflinching peace activist, has this effect on many people. But the comprehensive and at times unsettling new documentary, Joan Baez I Am a Noise, probes more deeply, beyond celebrity. Directed by Karen O’Connor, Miri Navasky and Maeve O’Boyle, with impressive access to Baez’s archives of drawings, journal entires, and a trove of meaningful relics in her late mother’s storage unit, the documentary finds Baez taking part in what she calls “the bone-shattering task of remembering”—remembering early racism, childhood abuse, an unloving father, and her experiences advocating for peace in Vietnam. Just before the film’s release by Magnolia Pictures, Baez and Fonda delved into it all, from lunch with Martin Luther King Jr. at his favorite restaurant in Mississippi to Baez’s passionate love affair with Bob Dylan—and much more.

———

JANE FONDA: Joan, I don’t know if you know that, in my 20s, I lived in France and got married there. And I was totally obsessed with you. I read articles about how you lived as this free spirit. How everything you owned, you carried in a duffle bag. You slept on couches. I wanted to be you. Do you remember the first time we met?

JOAN BAEZ: In France?

FONDA: No.

BAEZ: Where, Jane?

FONDA: I was filming in Rome, and me and my then husband, the French director Roger Vadim, rented a very, very old castle outside of Rome. One afternoon, I looked out of the window and I saw John Philip Law lying in the grass out in the fields and this woman with dark hair and a lovely cotton dress blowing in the breeze. I thought, “Well, that’s interesting.” And I went downstairs to make dinner. I was making gazpacho and you came in. I couldn’t believe it. I was just gobsmacked. You took my hand and you said, “You have such beautiful hands.” I thought I was going to pass out. I thought you were the most beautiful woman I’d ever seen. So, I am honored to be interviewing you for Interview Magazine.

BAEZ: I would like it to be a conversation, though, because you and I have so much to share. I remember looking at your hands and thinking or saying you had the tiniest wrists in the world. Do you have any recollection of that brilliant observation?

FONDA: Yes, I do. And it’s true. I have the tiniest wrists in the world. Anyway, I just love this documentary. It’s unlike any documentary I’ve ever seen. It’s moving, it’s beautiful, and it’s extremely surprising. I had no idea that all these things were going on in your head, and so many of them parallel things that happened to me. Did you choose the people that made the documentary?

BAEZ: Yeah, it’s friends of mine. Karen O’Connor and I had been friends for decades and I knew she was a brilliant filmmaker. She knew me very well and I knew her very well. It was about trust, and it was about the fact that my family was gone and I could talk about the more personal stuff. I’m coming towards the autumn or winter of my life, and I wanted to make an honest legacy. So, I just handed them the keys to the storage unit of my life and said, “Go for it.” I wasn’t part of the filmmaking. I was just the subject.

FONDA: It’s brave of you to do that. The title sort of surprised me. Because you’re not noise. You’re gorgeous, angelic music.

BAEZ: When I was about 13, in spite of all the shyness, I was outspoken, and that’s how I managed to get attention one way or another.

FONDA: You’re inherently shy?

BAEZ: In some ways, I am. Probably not anymore, but certainly back when I was little. I was always the outside girl moving to a new town, and brown-skinned.

FONDA: Were you super aware of racism growing up as a Mexican girl?

BAEZ: I didn’t know what it was called, I just knew that I was not accepted in the world of Mexican kids and, at the same time, I wasn’t accepted in the white world because I was too brown.

FONDA: Do you remember when you first realized that you had a remarkable voice? It must have changed your whole life.

BAEZ: I was already taking refuge in my drawings and cartoons and stuff, and I could hold a note really well. I was in the chorus in the school and I wanted to be in the Triple Trio with all the cool white girls but I didn’t get in. So, I went home and I started wobbling my Adam’s apple up and down to get a vibrato. Once I had that, it’s this really frail little voice, but I thought, “I have a voice.” Somebody gave me a ukulele, and the rest is history.

FONDA: Thank god.

Joan Baez at the Alabama State Capitol in 1965, from JOAN BAEZ I AM A NOISE, a Magnolia Pictures release. © Stephen Somerstein. Photo courtesy of Magnolia Pictures.

BAEZ: Do you sing, Jane?

FONDA: Do I sing? I can carry a tune. I have no vibrato. I’m too old to develop anything new. But your fame, which I can attest to, people knew you and worshiped you all over the world, came so fast, right? Was it the Newport Jazz Festival where you were launched into the Stratosphere?

BAEZ: Yeah, I was.

FONDA: And overnight, and for so many decades, you were the sound of the peace movement. You were the sound of the voting rights movement. It must have had quite an effect on your family.

BAEZ: I learned from the film the different effects it had on my family because my sisters’ lives were molded in some ways around sister Joan. I had never heard them say what they really felt because you don’t really do that. I mean, I knew to some degree, but I never heard Pauline say, “Well, I just decided I couldn’t do it.” I just thought that she didn’t like society and wanted to go live in the hills. I didn’t realize how much I had to do with that.

FONDA: You say in the documentary that you stepped into the civil rights movement of nonviolent action and you knew that was where you belonged. Music alone was never enough for you, right? You always had to have your voice at the service of causes greater than you.

BAEZ: When I was just learning songs, I must’ve been 15, and I sang some rhythm and blues. The first song that resonated with me in a large way was Emmett Till. I really wanted to deliver that song. I was still playing the ukulele, so that mold of the music and social conscience together started that whole trajectory for me.

FONDA: I’ve watched the documentary three times now and I loved it more each time. What I noticed the last time was the tone of your father’s voice when he suggested that what you did and do wasn’t really work.

BAEZ: It’s complicated. He was unable to really say to my face, “That was a great concert.” He just couldn’t do it. It was very deflective. But it was his MO. I mean, he had been raised that way. A couple of the stories that he told me about his childhood, how his mother would berate him when he was trying to play the piano, he’d laugh while he was telling it, and I’d said, “I don’t think that’s very funny.” He said, “Well, she was right. I wasn’t playing it well.” So, his background was not one of people really congratulating him.

FONDA: Well, you’ve learned to forgive, but did it make you sad at the time? Or angry?

BAEZ: I didn’t even notice it because that’s all I knew. And then, when I started to come out of deeper therapy, it became clearer and clearer to me that that was a deficit in my life. Now, if this is allegedly a conversation, do you get to talk about your relationship with your dad?

FONDA: Oh, yeah, Dad occasionally told me that he was proud of me, but when he would have an interview, he would tell other people how proud he was. But if I did a performance that was in any way sexual, he hated it.

BAEZ: That was it. My dad once called and said I didn’t need all those drums on the album because he was insinuating that they were tribal, weird, sexual. He said, “Rhythm didn’t come till after the music.” And I said, “Well, Papa, that’s not true. Rhythm came first.” But it was the sexual issue he couldn’t deal with.

FONDA: God. I just remembered, I stayed in Hanoi in 1972 in the same hotel that you had stayed in previously. The first night I was there, there was an air raid because the war was still going on. They took me down to this bomb shelter in the basement, and then they told me, “When Joan Baez was in the bomb shelter, she sang for us.”

BAEZ: Oh god, you tell them to go fuck themselves.

FONDA: I was so jealous. I mean, to have a voice like yours, you don’t have to carry anything around. It’s just your gift that you could bring everywhere you go. I don’t think they said you even had a guitar or a ukulele.

BAEZ: I had a guitar. But probably not in the shelter.

FONDA: It was a very small, very low ceiling and you had to duck down. Do you remember it?

BAEZ: I do. I went back to visit. It was a little bit shattering and amazing.

FONDA: Was it hard?

BAEZ: I have such a terrific blocking system. A lot of people say, “Oh, you’re so courageous.” I’m just kind of dumb sometimes. If we didn’t live in denial 90% of the time, we’d all blow our own brains out.

FONDA: It’s so interesting that you say that. I woke up the other night and it was so clear to me that all through my life it’s been luck, not intelligence or wisdom, but pure luck in the face of utter foolishness, that I’m still alive. Did you get scared when you were there under the bombs?

BAEZ: The only time I got scared was when the bombs got close. The planes are in the distance, and we’re still talking and telling jokes. They get closer and closer, it gets quieter and quieter, and all the atheists are saying, “Dear god, oh dear god.” That’s what happens at the end and I would be scared. And then, as they fly away, everybody starts chatting again.

FONDA: Do you remember they had those manholes that lined all the streets, and then they had about a four-inch thick straw lid to keep the shrapnel away? I got pulled into one of those by a young Vietnamese girl. It’s only meant for one person, so we were sandwiched together. I could feel her eyelashes and her breath on my cheek and the ground was shaking. The bombs were really, really close. This was out in the countryside.

BAEZ: What year was this, Jane?

FONDA: ’72. And when it was over, I kept saying to her, “I’m sorry, I’m so sorry.” And she went to the translator, and he translated, “Don’t be sorry. We know why we’re fighting, but your men don’t know. So you should feel sorry for your people.”

BAEZ: Oh boy.

FONDA: It absolutely blew my mind. She must’ve been 14 or 15, something like that. Did you learn a lot while you were there?

BAEZ: I learned that I was mortal. I hadn’t really thought about it. And then, when I saw the body part of a child, I think that’s the first time I’d ever realized that I was really mortal.

FONDA: What it did to me was completely revise my sense of strength. Here were these people that had no heavy equipment, they didn’t have heavy industry. They were a country of peasants and fishermen, and they were winning. It makes you think, “What makes strength?” It’s not the solid oak tree that stands there rigid. It’s the bamboos all tied together in one big bulk that you can’t cut them down.

BAEZ: That’s a nice analogy.

FONDA: Let’s see what other questions I have here. Oh, I’m so happy that the documentary includes your artwork. Do people realize that you’re not only a brilliant singer, but you’re the most wonderful artist?

BAEZ: Well, they will now!

FONDA: It made me realize that not only are you a drawing artist, but that you’ve managed to do something that is not easy but is very important. You’ve managed to grow up without losing childlike-ness. Did you know from the start, when you began to think about the documentary, that you wanted to go to a place that you had not revealed publicly? Early abuse and—

BAEZ: Yeah, part of it was that I thought it would be helpful to people who’d been through what I’d been through.

FONDA: I showed it to my assistant, because she adores you, and she thinks it’s the best documentary she’s ever seen. I said, “Did you get the sense at the end that she is in the best place she’s ever been, that she has recovered from all this?” And she said, “Absolutely.”

BAEZ: Oh, good.

FONDA: I wasn’t sure. For me, there was still a great sadness present, but there can be two things at once.

BAEZ: Yeah. And you know exactly about the state of the world, the situation we’re in, and the sadness. It’s not paranoia. It’s real. We’re losing our billions of birds. That’s enough to set me into a deep sadness, but that sadness is not depression and anxiety and craziness and hopping in and out of bed with people.

FONDA: It’s interesting that you mentioned the birds. The fact that we have 2.9 billion fewer birds in North America, it sent me to bed. It did me in, for some reason. Because I grew up with meadowlarks and whippoorwills and mourning doves, and then they were falling dead out of the sky.

BAEZ: Oh, god. I know. Part of the job I see for myself is to listen to a bird sing and not wait for the chorus and be disappointed that it’s not there. I have to listen more carefully and more attentively to the song that they’re offering. That’s not been easy.

FONDA: Greta Thunberg said, “Everybody goes looking for hope, but don’t look for hope. Look for action, and hope will come.” Don’t you find that’s true?

BAEZ: I agree. I also heard from somebody the other day, “Hope is a discipline.”

FONDA: It’s a muscle, like the heart. Optimism is “everything is going to be fine,” but you don’t do anything to make it so. Hope is a muscle. Hope is when you’re trying to make it so, and you’re with other people who are doing the same thing.

BAEZ: That’s wonderful. I’m going to write that one down. I need help in the hope department.

FONDA: We all do, and we also all have to understand that feeling depressed right now is a sign that you care. It means that you are tuned into nature and life, and you’re aware of what’s happening, and it’s okay to feel that.

BAEZ: Now, when I have questions or certain disturbances that I’m unable to solve on my own, I go to a tree. There is a magnificent tree across the street named “The Counselor.” Years ago, when Shirley MacLaine wrote “Out on a Limb,” I thought, “Oh, this woman is bonkers. This is so ridiculous, talking to trees. What other bullshit is she going to come up with?” In my opinion, she was right on all of it. So, yeah. I started talking to trees about 15 years ago, more than that maybe, when the tree next door was going to be cut down. I went over and started talking to the tree about it, and I said, “Are you okay? How are you feeling about this?” Tree says, “Well, I’d rather be cut down with a ceremony than fall on somebody’s house.” So I started these ceremonies and banging on drums. The neighbors were tolerant. “Do you have any requests?” I asked the tree. He said, “Yes, when I’m down, put a blue blanket over my stump.” And I said, “Sure, why?” He said, “Well, I’ll think it’s the sky.”

FONDA: Oh my god.

BAEZ: So I realized then that there was this interchange between myself and trees. Are you agreeing with me, Jane?

FONDA: I’m agreeing and I’m so moved. Because what you’re describing is the main thing that’s missing from this world right now. We’re cut off from nature. Nature wants to talk to us, and we don’t know how to listen anymore.

BAEZ: I also think people, the same as they might need permission from my own traumas to talk about their traumas, need permission to talk to trees. The tree is my therapist. I haven’t seen a therapist for a number of years. I just go to the tree. Do you have any favorite trees, Jane?

FONDA: I dissed an oak tree at the beginning of our conversation, comparing it to bunched-up bamboos, but I love oaks, especially California Oaks, because I grew up with them. There was a particular tree that I would climb to the top of and have fantasies and visions of my future life. Yeah, I’m a tree whore. I love trees.

BAEZ: Wonderful. Yeah, I’ve heard about that with you.

FONDA: I was surprised when you talked in the documentary about being in your 50s when you realized that you weren’t gifted at intimacy in your relations, with men or women. You don’t mean sexual intimacy, right? What do you mean by that?

BAEZ: Well, it boils down a lot of times to sexual. I skittered around it to the point where I couldn’t have a lasting relationship. So, in a way, you have to exclude the intimacy from the sexuality, because the intimacy means you care about the person, you’ll share in a way that I was unable to share. I needed to control the situation and I was incapable of having a really equal intimacy with somebody. In the film, I’m joking about being no good at intimacy with one person, but great with intimacy with 2,000, because you can’t be intimate with 2,000 people.

FONDA: No. But it expresses the idea perfectly, and I think it’s true of so many people who have big audiences but have a hard time being intimate. I’m a little bit that way. I always blamed the people I was in relationship with. I can be intimate with girls, with women, but not with men, and I always thought it was their fault.

BAEZ: Of course it was, but I admire you for bashing on through and marrying these guys and making lives with them.

FONDA: I always tried hard, and then I always had to leave. Now I fantasize about being with a totally different kind of man, an artist or a professor and not a very public person. Maybe now I could make a go of it. My favorite ex-husband, Ted Turner, always said to me, “If you don’t lose it, it grows over.” It’s true, so it’s too late for me now. I’ve closed up shop. Do you ever wonder, now that you have worked through so many of these issues, if you could have a long-term relationship?

BAEZ: The joke is that when I was finished with the bulk of this work, looking peaceful and able to do things I couldn’t do, like sleeping through the night, I got the right meds figured out, I had no desire to take the next step. I always figured if somebody crossed my path that it would be worth trying. But I think my blinders are really careful. I must have passed by a lot of people, and I’m just not willing, throughout my otherwise quite happy life, to do that kind of work.

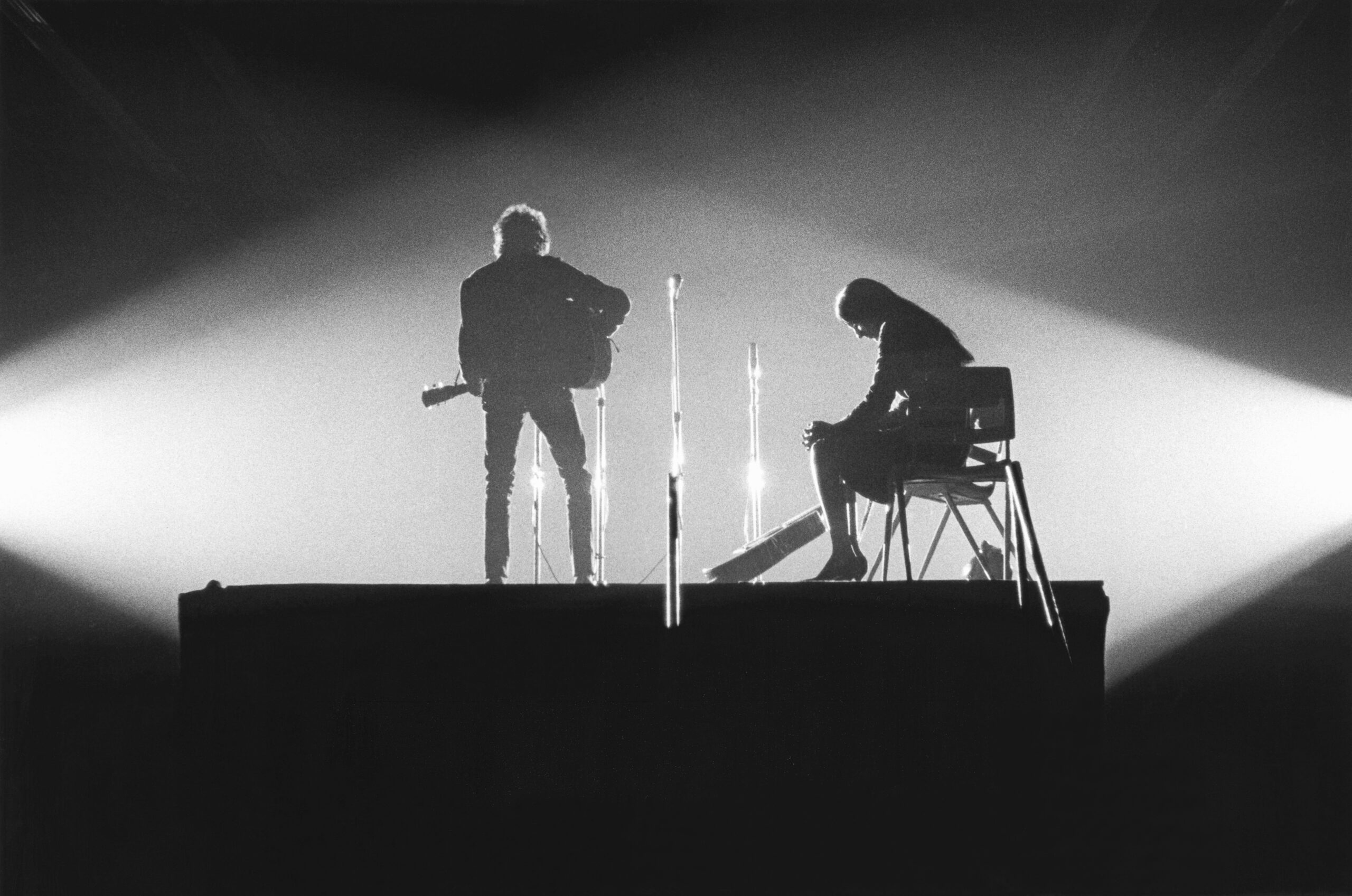

FONDA: I agree with you. I’m in the same place. People are going to be so excited to see you and Bob Dylan during your love affair. It’s such fun seeing you both so young and playful. And he actually seems happy. You never see Dylan happy.

BAEZ: I know. I hadn’t seen that footage before and I just love it. We had our baby fat. We were so young.

FONDA: When the two of you are singing “It Ain’t Me Babe” together, you look like you’re goosing each other behind your backs, or like you just finished making love, because your faces are so full of sex and desire and secrets. It’s just juicy and priceless. Did you stay close to him? You say in the movie that that breakup really just broke your heart.

BAEZ: Yeah, it did. It was because that was the deepest. When somebody walks away from you, that’s the pain. If you walk away, or it’s a mutual thing, it’s not that deep, deep hurt and regret that I suffered. Because when Bob vanished, he just vanished. We came back around and we did Rolling Thunder and that was fun, but it was a distance that I understood, and that was okay. But that initial baby fat period was pretty wonderful.

FONDA: I wouldn’t be surprised if he didn’t also suffer from intimacy problems, because from the other documentary I’ve seen of him, it doesn’t seem that he has much intimacy ability.

BAEZ: I have no idea.

FONDA: What was Jerry Garcia like?

BAEZ: You know, you ask me that. But I never slept with Jerry Garcia.

FONDA: You didn’t?

BAEZ: No. I slept with his drummer. I slept with Mickey Hart.

FONDA: Oh, that’s—

BAEZ: By the way, I did not sleep with your ex-husband.

FONDA: I know. Isn’t it interesting that he told me he slept with you? While I was in Hanoi, no less.

BAEZ: I wouldn’t let that out, because I was so shocked by that. Anyway, under the bridge. Move on. Oh, I have a question for you. When you say you folded up shop or, I call it zipping myself up, do you still feel like a sexual individual, and desirable?

FONDA: I have no desire to have sex and yet I dream about it a lot. I’m so glad I’m single. I’ve been with guys all my life, either married or almost married, and I’m just so glad that I live alone and I can do whatever I want. I like that feeling. Don’t you?

BAEZ: I do, and I’m curious about myself and people’s responses to myself at my age. Am I still attractive? Am I still desirable? I don’t want to sleep with anybody, but I like to flirt and be flirted with, and I don’t know where that starts and ends.

FONDA: If I was to sleep with somebody, it would have to be someone very young. I mean, like in their 20s.

BAEZ: Hey, let’s hear it.

FONDA: Yeah. Old guys sometimes start to flirt with me, and it’s, “I’m sorry, but—”

BAEZ: I’m sorry, too. I was always about cheekbones, very young, so now it’s all coming out.

FONDA: You didn’t have cheekbones for a long time. You had a round face. I did too and I hated my face. I hated the fact that I had no shape. It’s one reason I became anorexic and bulimic and all that. Did you ever suffer any stuff like that?

BAEZ: No. People ask me if I ever had an eating problem, and I said, “No,” because I figured that meant you were either anorexic or fat. So no, I was just so terrified of throwing up that I wouldn’t eat anything. It would have to be no threat to me to eat something, and so I was very thin. That took a long time to get over.

FONDA: While we’re on the subject of men, David Harris.

BAEZ: Yes.

FONDA: You married David Harris, who was a prominent activist against the war in Vietnam, who is absolutely adorable in this movie. David didn’t age well, and I saw him later on in his life a few times, but oh my god, he was just gorgeous and adorable and you just want to eat him up. He was sent to prison for draft resistance. One, you were married to him and you were pregnant with your son. That must’ve been really hard for you.

BAEZ: I think what was hard was that I wanted so badly to be what I of course couldn’t be. I wanted to be a wonderful wife. I wanted to be a wonderful mom. I wanted to have a whole stack of kids. I wanted to be cooking and making biscuits or whatever the hell, and none of that was possible. I had one beautiful son, and in the film he describes in an eloquent and elegant and forgiving way what it was like to have an absentee mom. For years, I didn’t understand it, and now I do. We’ve worked the rest of our lifetimes since those discoveries to care about each other, to love each other, and to be pals. And that took a lot of work, Jane. Watching your documentary, it was so parallel to mine. Even when I was present, I wasn’t present. You and I were running for the telephone to organize the next march and holding the kid in one arm, thinking we were being a great mom.

FONDA: Were you holding the kid in your arm when you were doing that? Because often, I wasn’t.

BAEZ: A lot of the time I was and then, of course, I was gone so much.

FONDA: Did he hold a grudge for a long time?

BAEZ: I am sure. But I think abandonment is even harder than some kinds of abuse, because there’s nothing to grab onto. It was just kind of this floating emptiness. And so he couldn’t accuse me, but he took a lot of psychedelics and he took a lot of drugs. I’m eternally grateful to the Grateful Dead because he had a home there. And I’ve thanked them. And I had the most wonderful therapists. We did everything.

FONDA: What does that mean?

BAEZ: That means that we started for probably a year setting this thing up, so that I knew him, that he knew me, I was safe. And then we started down the hypnosis stairs. That took a number of tries because I was so scared. I would start down and come popping up again. And then little by little I made it down, to where some of those memories are. We all have them. I had fantasies all my life of going to a hospital because it would be safe. The nurses would take care of me, sheets are clean. So I checked myself into a women’s hospital, which was all about women’s issues. A lot of them were weight issues, and then some were abuse. I was there for six weeks, and about halfway through, I just threw a cup at a wall and grabbed everything off the nurse’s station and threw it and started screaming, “Help me, help me, help me.” And that’s when the memories started coming. I started getting help, and then I could leave there having burst this pustule.

FONDA: Wow. Is it important for survivors who have totally blocked the memories of abuse to try and retrieve them? What’s to be gained?

BAEZ: Well, there are new theories now that you don’t have to go through all this stuff. They’re retraumatizing. I’m just happy that I did it my way, even if it was traumatizing, because I got this family out of it, this whole rainbow of a life out of it. For some people, it’s not that big a deal and doesn’t interrupt their life. But my life was so interrupted for years, living from one panic attack to the next.

FONDA: It was a huge, huge surprise to me to find this out in the documentary. I’m so sorry that you had to go through that.

BAEZ: Oh, thank you so much.

FONDA: When you have time, Joan, read Sally Fields’s book. It’s called In Pieces.

BAEZ: Okay. Similar stuff?

FONDA: Similar stuff, similar personalities.

BAEZ: I’ll do that.

FONDA: It’s beautifully done. She’s a close friend, and I know it would mean a lot.

BAEZ: Say hello for me, will you?

FONDA: Yeah. Do you know her? She’s wonderful.

BAEZ: It’s the matching wounds, Jane. We draw those people to us. I mean, it is miraculous, remember that line, “in a crowded room we will find that person.

FONDA: You know right away. Anyway, what was Martin Luther King like?

BAEZ: He was a riot.

FONDA: Really?

BAEZ: He was a riot. He didn’t get to show his fun and funny side because the anti-King people were waiting for anything they could jump on. So if he told a joke or acted silly, that would be enough to set off another whole attack. But when he was out of the pulpit, he was very funny. And I’ll tell this story because it’s fun about the whole movement. Andy Young, Jesse Jackson, Jim Foreman and I went to pick King up at the airport coming into Grenada, Mississippi. I was thinking, “Ah, I’m going to hear how they organize marches. This is so exciting.” And we picked up King and they all told jokes. Some of them were very racial and had hysterical laughter. We stopped at King’s favorite little restaurant. He ordered chicken, okra, mashed potatoes, laughing and goofing around the whole time. Got in the car, went back to where the conference was, and not a word about a march. Later that day, I said, “Andy, I thought I was going to learn how you guys organized the march.” And he said, “You just did.” That’s how they do it. It’s all spontaneous. And at any rate, that was King.

FONDA: That’s very different from what the Vietnamese did. When I went back to Vietnam with Tom and Haskell Wexler and we made a documentary, at one point one of the Vietnamese leaders of the group said, “We’d win this war much faster, except we always have such long meetings.”

BAEZ: I have a question. When do you and I get to have tea together?

FONDA: Well, when I’m up there again. You live in Marin County?

BAEZ: No, I live Woodside.

FONDA: I was just there. If you’re famous and you get cancer, every hospital wants you to speak and they use you to raise money. So I started researching with the guy named Gary Cohen, who founded Healthcare Without Harm, and what I found out is that the medical care system has invested $4.9 billion in fossil fuels. They use fossil fuels everywhere in their work. Gary Cohen and his organization have gotten a thousand hospitals so far to start phasing out of fossil fuels. So I make speeches now about what they should do to join the campaign to stop the climate crisis. Gavin Newsom finally signed a bill that created a 3,200-foot setback from communities, so new oil wells can’t go next to people’s homes. So I’m raising money and I’m coming there to that area. I can stay an extra day.