DIRECTOR

How Director Mikko Mäkelä Flipped the Script on the Modern Sex Work Movie

As tabloids sniff up the latest OnlyFans sensation, the workers themselves are surveilled, fired, and mauled by the masses, calling to mind what Lizzie Borden called “whorephobia” in her 2022 feminist anthology of the same name. When I sat down with Mikko Mäkelä, whose most recent project fills holes (figuratively, and literally) in our collective memory regarding sex work, he told me, “What I was really wanting to focus on was a depiction of sex work as something that can be empowering and something that one can enjoy. It’s a valid choice and it doesn’t have to be questioned and it’s not something that someone needs to be saved from.”

Sebastian, the Finnish filmmaker’s sophomore feature, follows Max, a 25-year-old aspiring novelist who pursues a double life, moonlighting as a sex worker under the alias Sebastian in order to gather writing material. It’s revealed, however, that Sebastian’s encounters with multiple older men not only offer intergenerational oral transmissions of gay history and culture, but open up alternative modes of communication and portals of desires. “It’s also a depiction of someone for whom sex is an essential way of connecting with the world,” the director explains. “If we didn’t see that side of him, we would be cut off from a lot of his personality.” On a rare sunlit day in London, Mäkelä and I celebrated his film’s wide release by chatting about everything from working with intimacy coordinators, living for your art, and the gray zone encompassing desire and commodification.

———

LILY KWAK: You’ve mentioned before that this film was an opportunity for you to depict sex work as a choice, where it’s often depicted as a last resort. There’s a clip in the film where Max is talking to a professor he’s seeing and the professor asks him, “Is it really just about the money for you?” And he responds, “It’s not that simple.” How do you think depictions of sex work in contemporary films compare to public perception of sex work?

MIKKO MÄKELÄ: There was definitely a need to depict the phenomenon of sex work facilitated through the digital means that I was observing in London. I didn’t feel that there were films that were looking at it in the way I hope to have done in Sebastian, where it really has become just another option in the gig economy. What I wanted to also focus on was a depiction of sex work as something that can be empowering and something that one can enjoy. It’s a valid choice and it doesn’t have to be questioned and it’s not something that someone needs to be saved from. I don’t think we’ve seen a huge number of sex worker films depicted like that, even though there’s obviously a lot more conversation in the culture about sex work and more positive accounts about sex work from sex workers themselves. But a lot of the tropes we’ve been used to seeing in cinema are still very much alive in more recent sex worker films as well.

KWAK: I was reading a review in The New York Times that said, “Oh, there’s so much sex in this film.” I thought that was interesting because there’s a moment in the film when Max’s editor is telling Max that there’s too much sex in his book. How do you conceive of sex depiction on film and of sex as an essential mode of self-expression or communication?

MÄKELÄ: Absolutely. Of course, sex tends to be in a nonverbal mode of communication, which is partly why less focus is placed on it. But because it’s something that we’ve shied away from, I really think that it’s underused and undervalued in film. I’ve always found myself drawn to depicting intimacy in various forms, but certainly on Max’s journey, which is also very much about communication and looking for connection as well. I wouldn’t have been able to tell that story without sex scenes. He’s learning so much about himself and about other people. As a character, in his daytime life and as Sebastian, he’s quite closed off in some ways. Those moments of the sexual encounters allow for him to express different aspects of himself and explore different sides of himself that he doesn’t necessarily feel so connected to in his life otherwise. So absolutely, it’s also a depiction of someone for whom sex is an essential way of connecting with the world. If we didn’t see that side of him, we would be cut off from a lot of his personality.

KWAK: Max is someone who lives for his art. It’s through his art or through his sexual encounters that he seems to be able to get closer to what he feels is his truth.

MÄKELÄ: The primary question for me was that, for someone who is using their life for their art and, I suppose, living their life in reference to it and knowing that they will be drawing on what they experience in their life and what they see in their life, I was really intrigued to think about that ground in the middle, between their sense of self as a human being and the work that they are kind of projecting themselves into. When those things become completely wound up with each other, it raises those questions about whether what we are experiencing in our lives is real for me as a human being, [or] if it’s always with reference to that art. I don’t have an answer to those questions, but those were the things that really animated me when thinking about the story.

KWAK: When I was watching your film, I was thinking about the political context in New York around sex work. In February, a trans activist named Cecilia Gentili suddenly passed. Her death helped mount a fresh push to decriminalize sex work at a rally in Albany this May. You’ve mentioned that this film was informed by growing up in Finland, as well as your experiences in the London queer scene. Were there any particular political contexts that informed the writing of your film?

MÄKELÄ: Yeah, certainly the atmosphere in Finland in relation to LGBTQ rights has evolved a great deal over the last 15 years since I moved to the UK. But in terms of thinking about attitudes to sex work, coming to London, I was inspired by witnessing people’s sense of freedom from shame or stigma. It’s mad that sex work is still criminalized in so many countries. Even if we think about the context of the Nordic countries as well, a country like Sweden that we think of as so supposedly progressive and kind of advanced is held up as this kind of progressive model, but sex work is illegal in Sweden. It’s legal in Finland. It’s legal in the UK. Of course, there is potential for exploitation within sex work. It’s dangerous. But I think the advocates for keeping sex work criminalized often hold such outdated views of sex work that it’s so far away from the experiences that I’ve heard of, and those of people I know in London who are very much self-empowered entrepreneurs making choices about their bodies.

KWAK: I was reading Sophia Giovannitti‘s Working Girl: Selling Art and Selling Sex around the same time I was watching your film, which is preoccupied with how art and sex occupy similar positions as capitalism’s stress points. It’s interesting too, because Sophia eventually collapsed her identities as an artist, writer and sex worker. Can you talk about the choices that went into deciding how to close your film?

MÄKELÄ: Yeah, what I was wanting to illustrate in a sort of ironic parallel was that the way that Max as the writer and the young artist ends up being commodified by the publishing industry isn’t necessarily that dissimilar from the way that he’s then commodifying himself as a sex worker as Sebastian. I wanted to lightly satirize the way in which he gets kind of pushed and pulled by the publishing world through that kind of image-making, how he’s sold then and packaged as a young writer to feed that system.

KWAK: I loved that scene when Max is sitting in front of the photographer to promote his book and the photographer is like, “Be thoughtful. Don’t look sexy.” And his face completely changes within a second.

MÄKELÄ: Right. It’s not necessarily so dissimilar from the ways in which he’s packaging himself on “Dreamy Guys” and trying to please that potential pool of clients as well. I was very much wanting to explore the idea of the challenges of making art within a commercial system and all the compromises that may necessitate, and the ways in which you need to navigate that to try to hold onto a sense of authentic voice. Certainly within that system, art isn’t sacred in the way that it might be idealized. For Max, collapsing those two identities—of the writer and public figure, and the sex worker—is very much about overcoming his own internalized sense of judgment and shame, more so than anything he has necessarily directly felt from the society around him. But of course, in living openly he will still have a lot of privilege to protect him in a way that not all sex workers do.

KWAK: You’ve noted that your intimacy coordinator was a crucial part of your production. What was the process of staging those sex scenes?

MÄKELÄ: They were already very detailed in the script because they are such an integral part of telling the story and the character’s journey and couldn’t be left down to just crafting choreography on the day. But it was really, really great to work with an intimacy coordinator on the project, and it was important to find someone who was sex-positive and had close familiarity with queer sex. It is still such a new field and kind of a new role, and I think a lot of people also have different interpretations about what it entails. I’ve definitely heard a lot of discourse in the media from intimacy coordinators, who might themselves be questioning the place of sex in a film or the necessity of sex scenes. It was very important to work with someone who didn’t question that and who was on the same page about the value of sex scenes for the narrative. The intimacy coordinator, Rufai Ajala, and I went through all of the scenes in the script, discussing what each one means for the character and for the story, but also importantly how they should feel and what the mood is, what the atmosphere is and how I’m imagining the choreography, how I’m imagining the motion. They then did a lot of work with the actors in going through their boundaries and checking in about what they were comfortable with and not. I found them crucially useful for the way that they were able to quickly craft a sense of trust between all these actors, since some of them would only be on set for a day or two.

KWAK: What are you doing when you’re not working on your films?

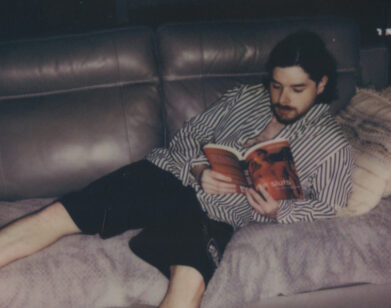

MÄKELÄ: I’m trying to maintain some sense of looking after my health and some exercise and sleep. Reading and watching other films is always the top of my list after my own work.

KWAK: What have you been reading or watching recently?

MÄKELÄ: I’ve been reading Doris Lessing’s autobiography. I’m very interested in her essays as a writer and as a literary figure and as an activist during the twentieth century. I have to admit that I’ve had less time to watch things as I wanted to, but I’ve been watching quite a few films on planes, traveling between festivals.

KWAK: It’s very meta now that we’re having this conversation for Interview because there’s a clip of Bret Easton Ellis’s Interview article featured in the film, who serves as an idol for Max in many ways.

MÄKELÄ: That’s right.

KWAK: Thank you for your work.

MÄKELÄ: Very happy to be speaking to you.