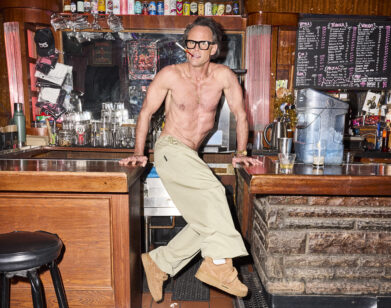

Holly Hunter

HOLLY HUNTER IN NEW YORK CITY, JUNE 2017. PHOTOS: DAVID NEEDLEMAN/JONES MANAGEMENT. STYLING: ASHLEY PRUITT. HAIR: CECILIA ROMERO FOR EXCLUSIVE ARTISTS USING NATURIA EXTRA GENTLE DETANGLING SPRAY BY RENÉ FURTERER. MAKEUP: NICK BAROSE FOR EXCLUSIVE ARTISTS USING LANCÔME TEINT IDOLE. STYLING ASSISTANT: ANNMARIE FIORAVANTE. RETOUCHING: FEATHER CREATIVE.

What is your favorite Holly Hunter film? Take your time; there’s no rush. Maybe your initial thought is James L. Brooks’ Broadcast News (1987), for which Hunter received her first Oscar nomination. Or Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993), the movie for which she won that most coveted of acting awards. Perhaps you gravitate more towards Hunter’s work with the Coen brothers in Raising Arizona (1987) and O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000). Or her other Oscar-nominated performances in The Firm (1994) and Thirteen (2003).

Intensely private about her personal life, Hunter, who was raised in Georgia, has long been one of the U.S.’s great character actresses. Fortunately, she has no plans to slow down: this month sees the release of two new films featuring Hunter, the Sundance comedy The Big Sick, in which she plays a mother whose daughter is in a medically-induced coma, and Strange Weather, an indie film about a woman searching for answers after the untimely death of her son. She has several more projects in the works, including Alan Ball’s upcoming series Here, Now with Tim Robbins, and a sequel to the hugely successful 2004 animated film The Incredibles.

Here, Hunter talks to her friend and fellow actor, Laura Dern. Though they’ve yet to work together, they’ve known each other for many years, and have been fantasizing about their first joint project since the early 1990s.

LAURA DERN: I’m so interested in knowing the things I never get to ask you as a friend, because they sound like I’m interviewing you and so I get shy. Now I have an excuse. I feel like we wondered about the same things at an early age—things that interested us about people and about the kinds of characters we’d want to play. But I had two parents who were doing that every day around me. I looked at it, and I saw, “Play the most complicated character in the room. Don’t be afraid to play someone people see as the bad guy or flawed, or the guy who kills John Wayne.” I remember as a kid going, “Okay, that’s brave acting. You make that choice that others might not want to make.” My mother and my godmother were actresses and they weren’t about glamor, they were about playing characters. It wasn’t that hard to figure out; it was around me, and I went, “This is interesting. I want to do that.” But how did you find it? Not just a love of acting, but this judgment-less interest in characters, where did that come from?

HOLLY HUNTER: When I was nine years old, I started playing the piano. I was obsessed. I wouldn’t go spend the night with any girlfriend if her family didn’t have a piano. I needed to play every day and for several hours every day. But I wasn’t great. I was good and I had tremendous passion, but I wasn’t fabulous. I didn’t have real technical skill, so no matter how much I practiced, I was never going to be able to really play in front of people. I had tremendous stage fright. But the piano was the beginning of me going, “I need an outlet. I need a vehicle.” And then from music, I joined the drama club in high school. I got on stage and I went, “Oh wow. No stage fright.” I couldn’t do public speaking, and I couldn’t play the piano in front of people, but I could act. I found that being on stage, I felt, “This is home.” I felt an immediate right thing, and the exchange between the audience and the actors on stage was so fulfilling. I just went, “That is the conversation I want to have.” It was unequivocal. There was nobody acting in my family, but there didn’t need to be. That conduit was so direct, I just went, “This is what I want to do.”

DERN: The directors that found you, and who you found, so early on in your career—

HUNTER: You and I could talk about that also.

DERN: We’re so lucky. It’s crazy.

HUNTER: Yeah, that was a certain kismet. There was a period in the ’80s where you had people who were born to direct, born to shepherd stories. Like [David] Lynch, who was so unusual, such a rare storyteller, so personal and private, and dream-like from his subconscious.

DERN: Like the Coen brothers. And there were only a few that we could speak to.

HUNTER: Like Jim Brooks with Broadcast News. People were like, “How come you don’t direct, Holly?” Because I’ve worked with people where that’s what they were born to do, and it’s a little intimidating after you’ve worked with a rash of those people one after another. Then it’s like, “I like acting. Acting is good.” [laughs]

DERN: It is often my fellow actor that directs me a lot. Through their eyes or through a comment, they will let me know that I should try it again or go with it.

HUNTER: Isn’t that fun, too, to have that trust with actors? That’s really so cool.

DERN: Then I long for it—Holly, please direct me one day. Please. Let’s direct more things. But then again, I know what you mean, because we’ve both worked with Steven Spielberg. You can see him cutting the entire film as you’re shooting one take. He’s like, “Can we do it again? Because then that’s going to cut into this and that.” That’s it’s own kind of genius.

HUNTER: He is also totally not afraid of the actor; he doesn’t have any fear. Some people, you see that they’re more comfortable being around the crew and dealing with the editorial or the shot or the composition. Spielberg is right at home equally in both arenas. He loves actors.

DERN: It’s so beautiful. I did a play with Jim Brooks [Brooklyn Laundry in 1991]. I never got to do a film with him.

HUNTER: What was that like?

DERN: It was amazing because it was only about the writing and the acting.

HUNTER: Which is all he’s really interested in.

DERN: Yeah. He got to go for days on one monologue to make it perfect. I had one monologue, I think it opens the play, and he spent so much time to get it right. I’m basically talking to the audience, standing alone, describing the weather. It’s very rudimentary, the dialogue, saying what the weather is like that day.

HUNTER: Did he write it?

DERN: No, this writer from Brooklyn Lisa-Maria Radano wrote it. She was a new playwright and we did it with Woody Harrelson and Glenn Close. Jim seemed to have such a blast. We were trying to figure it out and I couldn’t get it, I couldn’t understand how to make it interesting at all. I was trying to make it honest, but it’s the weather. I was like, “I’m making this really authentic.” [laughs] It was starting the tone of this piece, which is very sad and dark, but a comedy. Then one day you hear that laugh, which is the greatest thing ever. He jumped up out of his seat in the back of the theater and was like, “You’ve got to describe the weather with your body! ‘The billowy clouds’—use your hips to say what billowy is and use your arms to say what lightning is like.” Super exaggerated—like a Twyla Tharp dance piece—and it was hilarious and the weirdest thing ever.

That thing that you and Jim did together—maybe Robert Altman is the only other filmmaker I’ve ever seen do this—where the emotion goes on too long. Your heartbreak, his stress and sweating and anxiety, they all go on longer than any movies or television would allow.

HUNTER: Longer than anybody else would do it. Right.

DERN: Which is so human.

HUNTER: Totally.

DERN: I feel like as a kid, one of my great teachers was The Andy Griffith Show. Every show would end with those two men sitting on the porch, talking. For, like, three minutes of television, of a sitcom, where they only had 26 minutes, he’d go “Yeah,” and then Andy would repeat, “Yeah.” [Hunter laughs] I don’t think I would have ever been that brave. But being brave to break the mold was the thing that we found ourselves in at the beginning of our careers—with Jim, with the Coen brothers, with David [Lynch].

HUNTER: Of course. Those guys were breaking rules where it’s like, “Maybe it doesn’t work if you do that.” It’s that idea of hanging with it for too long, but if you just keep hanging with it, then it’s going to become something else. It’s experimenting with the element of telling a story. That was one of the reasons why I was really provoked by [my new film] Strange Weather. Strange Weather has monologues, and I was like, “Oh wow. That’s wild.” Nobody does monologues. Maybe The Designated Mourner by Wally Shawn with Mike Nichols, but those are kind of talking-head monologues in a movie. It’s just a rarity to encounter the monologue. I was piqued by, “What that’s like?”

DERN: It’s been really amazing to grow up together, alongside each other, and to watch you work. You have always been true; there is not one second that is not the essence of the truth. That’s why you’re the greatest actress. You are so pure, and so authentic, and so real. But you were cast by the people we just referred to, instead of being cast as the daughter and then the girlfriend and then the mom on a formulated sitcom, which we both could have been in the ’80s. We both auditioned for them.

HUNTER: We both auditioned, and you got offered stuff like that and I got offered stuff like that.

DERN: And we didn’t do it.

HUNTER: We didn’t.

DERN: We worked with these filmmakers. We knew the sacrifice of it at the time; you worked on a limited budget to work with these amazing filmmakers who were doing something different. We would have always seen you be a truthful artist, but we got your essence because they wanted it revealed to us—because they cared as directors for us to see that. That’s the goal. That’s cinema history. We forever have the performances you’ve given, and will continue to give, because someone cared enough about going to broken, messy, grey places and not needing it to look palatable.

What I fell in love with [in Strange Weather], and want to hear about, is, instead of needing to tell a story and needing to show us your grief, you’re just living in those monologues. They’re so exciting, and so devastating. From the moment the movie opens, the thing that killed me the most is your eyes; it’s like your body is so anxious and so jacked up with the need to know the answer. At the beginning, there is a hollowness to how many years you’ve buried your grief, and then suddenly, the minute you get this bite that maybe you’re not going to be left with a story you can never solve, your eyes just light up. You go on this hunger mission to solve the unsolvable case of heartbreak. It just killed me.

HUNTER: Another one of the things that I love about the script so much is the banality of the hot dog story. The whole idea of a hot dog store turning into a franchise is such a young person’s dream—a kid’s dream in high school.

DERN: It’s incredibly inventive for this boy who came from nothing—he came from a place where the world, or certainly his community, would say, “You’re less than. You’re trash.” That incremental journey to an idea, to putting yourself out there, that’s what’s so heartbreaking. This delicate boy puts himself out there to one teacher, and he just crushes him.

HUNTER: Yeah. And of course we all have those moments we can go back to and go, “That was a crusher. I never really recovered from that one.” I loved that gesture in the movie and in the script. I also loved that my character parlays this grief that she’s not really willing to grapple with into, “But I can get some revenge. I can hook this caboose up to some rage.”

DERN: As a mom, it’s the most relatable feeling there is. It’s maybe the only time in my life I’ve felt the level of rage that others have described to me—if someone’s going to fuck with my kid. I’ll judge an 11-year-old if she’s sassy to my daughter; suddenly I’m all mean about the 11-year-old. [laughs] But what I also love when you’re talking about the banal, and your commitment to it as an actor and commitment as the character, is that the discovery also is banal. I was in tears watching the movie two nights ago, because I realized that I train my kids to find the kind, generous hearts of the world instead of explaining that there are opportunists, and there are people who are going to question you, judge you, be jealous of you, and put you down. That’s a part of life too. They might teach you as much about yourself as the great friend who’s not going to peer pressure you or lead you astray. Life is complicated. We miss stuff as parents, and people bring you down.

HUNTER: I loved how the story wraps around itself into this incredibly ironic look in the mirror that the character has. She is her own enemy in a way.

DERN: You gave us the opportunity to sit with all those feelings of what we wanted to happen for your character—the story we wanted to be to true for you to survive your grief. But that wasn’t the story. The story is, he committed suicide and your character will forever be left with that. It’s easy to say, “My kid smoked pot in high school and then he found his way. I fucked up, I wasn’t there and I didn’t listen and we had a hard divorce.” But if you lost your child, those questions and those judgments of self are your prison forever. That story in the film is why I hope you are acting into your 80s like my parents. We’re just getting to examine adult characters now, and fuck, this is hard. How do you start in the middle and spend the rest of your life not being steeped in regret and heartbreak? How do you move forward? And now we get to play all these women.

HUNTER: I was thinking, “So now you’re playing moms.” But I’ve always played moms. In Raising Arizona, I was playing someone who wanted to be a mom.

DERN: Exactly.

HUNTER: We both have done lots of different things. But the thing with the role of “mother” in our legacy, in world history, in world mythology, is that the role of “mother” encompasses all of the universe. From Medea, a woman who kills her children, on down. There is no limit to what you can express if you are representing that in a story. You just got nominated for an Emmy for playing a mother!

DERN: Are you talking yet about your adventure with Alan Ball [on the upcoming show Here, Now]?

HUNTER: Oh my god. Well, Alan Ball is one of those guys where I trust him.

DERN: Isn’t that great?

HUNTER: It’s like, I feel like Alan is maestro. It’s like, “I’m so happy to have a master—tell me what to do. What would you like me to offer you, Alan?” I’m bringing out my serving table for Alan, and that is a rare thing to want to do: “What banquet can I serve you, Alan?” [laughs]

DERN: Is it right that Tim [Robbins] is playing your husband?

HUNTER: Yeah.

DERN: Come on.

HUNTER: He’s incredible.

DERN: He’s incredible, and at the same time we were starting, he was starting and coming up with his own insane, brilliant, crazy adventures—writing, directing, acting, being a political subversive.

HUNTER: Both on stage and in film. Tim has this incredible appetite as well that he’s been exercising all these years. But it’s nothing but exciting to exchange with Alan.

DERN: I’m so interested in what your collaboration will be in exploring family.

HUNTER: The thing that Alan is so comfortable with is human being in opposition with himself. Everything lives in all of us and Alan is going to explore those things—we’re going to go there. The extremes and inconsistencies in people, in their own secret selves. He’s just unafraid of all of those illegal elements of us.

DERN: I don’t know if it was in a scene study class, or where I heard that I should chart my character’s journey as though there’s a beginning, middle, and end, and you find the qualities of the character and their essence, and you stick with that. [But] every day, I’m shocked by myself: “What? How did I respond that way? That’s not even who I am?” [laughs]

HUNTER: “That’s not what I believe!” [laughs]

DERN: After knowing ourselves for this many years, you think you’ve figured it out. The dynamic of what one single individual can bring out in you that you’ve never seen with anybody else—especially in intimate relationships—it’s just terrifying.

HUNTER: Totally terrifying. And Alan Ball is not terrified by that. Or if he is, it’s some byproduct that he skirts. I was talking to another friend of mine, an actor, about objectives, and often I work with, “What do I want from this person? Why do I want it? How am I going to go about getting it?” But then there are other things that come into play—the mystery part. It’s not linear, you can’t name it, you can’t put your hands on it, it doesn’t have a shape. It’s the mystery of acting. In a way, you just have to let it be and let it live.

DERN: Maybe it sounds elusive or esoteric, but the other mystery in the role is the gift of why it’s entered your psyche at this moment in your life, and the emotional parallels to something that is either very personal to us or that we walk through. That has never failed to amaze me.

HUNTER: Yes, but that also comes through in your work. You bring your sense of wonder about life to your role. It is something that’s just inherent in every woman that you play.

DERN: That’s how I feel about you.

HUNTER: It’s a sense of joy, and I saw that with the piece you did with Mike White, Enlightened, from the beginning to the middle to the end of that series. Your face in the elevator in the first episode, that is another side of joy. Joy is on the other side…

DERN: [laughs] Right, joy is on the other side of this door.

HUNTER: It just cracked me up and that’s never stopped cracking me up about you.

DERN: I remember when HBO did The Sopranos, hearing women say about Tony Soprano: “He’s a lethal killer, but I’m so turned on by him. He’s sexy somehow.” You don’t hear that about women characters; it’s like they’re one thing or another, and within the one thing, make it palatable, handleable. I wonder about your journey with that. For me, again, the people who chose me early helped me know as a teenager that the job of an actor is to immerse oneself fully in this human, and never look back at what people are going to think of me. But I see that people get burdened by it all the time. Have you bumped up against that, either with filmmakers putting it on you or you becoming self-aware? I feel really lucky that Instagram didn’t exist when we started—trying to immerse ourselves [in a role] and then being told, “You don’t have that many followers, so it’d be great to build that.”

HUNTER: When I found acting it was a need. I needed it big time. I think that my looks through the years have served me well because I was never a great beauty and I was never cast as a great beauty. My looks were not part of my transportation—certainly not in the typical leading lady role—so I never leaned on it and I never really made that a high value. I’ve always been kind of androgynous: there’s a lot of male and a lot of female in me. One of the reasons why I love being an actress, and I do say actress, is because it’s fun to play women who are both. That’s what we do: you experiment with the male and the female in any character that you ever take on. That balance, the yin and the yang of that, is always in play, certainly more in some senses than others. That’s one of the great opportunities we have as actresses, to explore that, because everybody is male and female. That was a great thing about [James] Gandolfini, he had a lot of female in him, and a tremendous amount of male. I guess because I was acting out of a need, the carapace didn’t come into play for me. Like you’re saying, there’s so much focus being put now on the artifice, on the external, and that might have killed me. I probably wouldn’t have been strong enough to fortify myself.

DERN: Also, that artifice says, “Stay the same. Be this thing. We’re going to capture this moment and a lot of people like this, so stay like that.” It’s built for a one-hit wonder.

HUNTER: On the flip side is the article I read about the yoga pants parade. Some guy in this small town took women to task on the internet about wearing yoga pants throughout the day. He said, “I don’t want to look at it, unless you’re 18 and you’re a model. I don’t want to see these women over 30 walking around in yoga pants. Can I just say that?” And all these women said “No. You don’t get to say that, pal,” and they found out where he lived and had a yoga pants parade on a Sunday. These local women walked down main street and past his house. I don’t know about the Instagram thing, but I do know that, in some ways, what is acceptable in terms of female presentation does get challenged on this global stage.

DERN: That’s the beautiful thing about getting to have a job that’s about mirroring. We get to mirror what happens in a culture like that: the insecurity or vulnerability or rage or anything about being a woman, about aging, about men’s perception of women. I’m about to start a movie on Sunday and I did my wardrobe fitting yesterday. The Laura me, who has been liking my life and doing press and looking for the pretty dress to wear on the talk show, was looking at these clothes at the fitting, not yet in the character, thinking, “Those are horrific.” I put this outfit on, the scariest and most hideous thing, and I looked in the mirror and I’ve never felt so happy.

HUNTER: [chuckles] What movie?

DERN: It’s an independent film that is based on this story of JT LeRoy. Do you know about JT LeRoy?

HUNTER: No.

DERN: There’s documentary on Netflix now, but there was an author called JT LeRoy who had phenomenal success and was on The New York Times best-seller list. A 15-year-old, non-gender specific boy from Tennessee who wrote these brilliant novels and was called the next golden author. But a 45-year-old woman actually wrote them.

HUNTER: Oh yes!

DERN: So I’m playing her.

HUNTER: Oh great! I have heard about this person.

DERN: It’s such a wild story.

HUNTER: That’s incredible. For this photoshoot for Interview magazine, I never looked in the mirror. It was so fun. I’ve never done that before. Normally, there’s a premeditation, but it was, “How does this feel? How does this fabric feel? Do I like it or do I not?” It was fun to go on a strictly visceral [reaction]. I actually heard, because I worked with a costume designer, that when Susan Sarandon did Dead Man Walking, she did all of her costume fittings without a mirror. She said, “I don’t what to know what they look like.” I’ve never forgotten that, and maybe Susan is the reason why I did the photoshoot and went, “I’m just not looking.” I’ve got all these people around whose job it is to look. It’s my job to be. There’s a mystery to clothes. The alchemy that can or does not occur. It’s that thing of how you present yourself to the world has cache; it has meaning and it has value to society. That’s a tight wire.

DERN: I remember when I started, the directors just chose everything. David always chose everything.

HUNTER: That’s fun. I never had that.

DERN: My favorite memory is when David and I made this very experimental film called Inland Empire. We shot in Paris with a Sony camcorder, just the two of us, no crew. He wrote the dialogue, I learned it, he shot with the camcorder, and the sound was the mic on top of the camcorder.

HUNTER: Who were you working with?

DERN: It was a monologue in a hotel room.

HUNTER: It was a monologue!

DERN: Yeah. He was like “Okay, now we need makeup and your costume.” So we walked down the Champs-Élysées, walked into a store, and he picked out the nightgown or whatever she was wearing. We bought a red lipstick, put it on, and shot. It’s the greatest memory of working for me. It’s kind of what we need to do, and we can now. We’re going to shoot our movie on your iPhone when we’re done with this interview. Guys, we’ve got to go, we have a movie to shoot and the iPhone is needed. [laughs]

HUNTER: That is much more fun. I worked with Terry Malick and I never saw the movie, but I didn’t care, because to work with him is just a totally opening thing of what’s possible—a whole other way to do a movie that I never dreamed of. The monologue with Lynch, how did that come out? Did you love what came out?

DERN: Oh yeah, I love it. It’s crazy.

HUNTER: How can I see it?

DERN: It’s on Netflix. It’s a three-hour movie and I play the four central characters in that movie. [laughs]

HUNTER: You play four people?

DERN: It might be five, he never told me. I don’t ask questions anymore, I just do what he tells me. We did it over three years. When we started, I was nursing Ellery, got pregnant with Jaya, and we wrapped in Poland with Jaya being one. When you see the movie you can think about my daughter. That’s her movie.

HUNTER: I’ve got to see that!

DERN: Again, it’s these delicious filmmakers creating a tribe so we can go off on a journey with a family to explore and invent. It’s radical, because so few do it genuinely.

HUNTER: It’s radical. They evoke these dreams I have, which is the company dream: we’ll live together in the house that we’ve shooting in and the house will be a practical house, a real house, and this will be our characters’ house, our family house. We will all live there as actors and we’ll cook together and maybe rehearse or not, we’ll go to the movies, we’ll drink, get hammered, go the beach, go to museums. We’ll have these lives together.

DERN: Let’s do that!

HUNTER: It’s a Cassavetian dream. That feeling you can get when you do the theater, when you’re with a company of actors and you are all living in the same motel and you’re going to the theater eight times a week and going to the bar every night after the show together. You form this crazy intimacy from the exertion of the intimate involvement of doing a great play. Alan [Ball]’s thing makes me fantasize about that. I don’t always have that fantasy, but he inspires that.

DERN: How beautiful. I want to do that. I remember hearing stories about films where people did that.

HUNTER: And then they are family for the rest of their lives. How actors can become very intimate so quickly with each other—that’s what we’re doing.

DERN: We have that. The intimacy of feeling like you know each other in a deep way, even if we haven’t worked together or spent lots of time together, there’s a kindred spirit.

HUNTER: We’re in the bowling league.

DERN: We’re in the bowling league. Maybe that’s our movie.

STRANGE WEATHER COMES OUT JULY 28, 2017. THE BIG SICK IS OUT NOW. LAURA DERN IS AN OSCAR-NOMINATED ACTOR, WHOSE RECENT CREDITS INCLUDE 99 HOMES, CERTAIN WOMEN, TWIN PEAKS, AND BIG LITTLE LIES, FOR WHICH DERN JUST RECEIVED AN EMMY NOMINATION.