Hiro Murai and Spike Jonze Try and Figure Out This Artist Thing

Cardboard camera by Mark Gonzalez.

For people of a certain age, the Directors Label series is a seminal text. Released in the early aughts and passed around from dorm room to dorm room like a prehistoric viral video, the DVD boxset spotlighted the work of filmmakers who were using music videos to push the boundaries of the form. Its creators—Michel Gondry, Chris Cunningham, and Spike Jonze—were the focus of the first three installments, which featured revelatory classics from the likes of Björk, Daft Punk, and Aphex Twin, and undoubtedly influenced an entire generation of aspiring filmmakers who saw what was possible with a modest budget, three-minute runtime, and a boundless imagination.

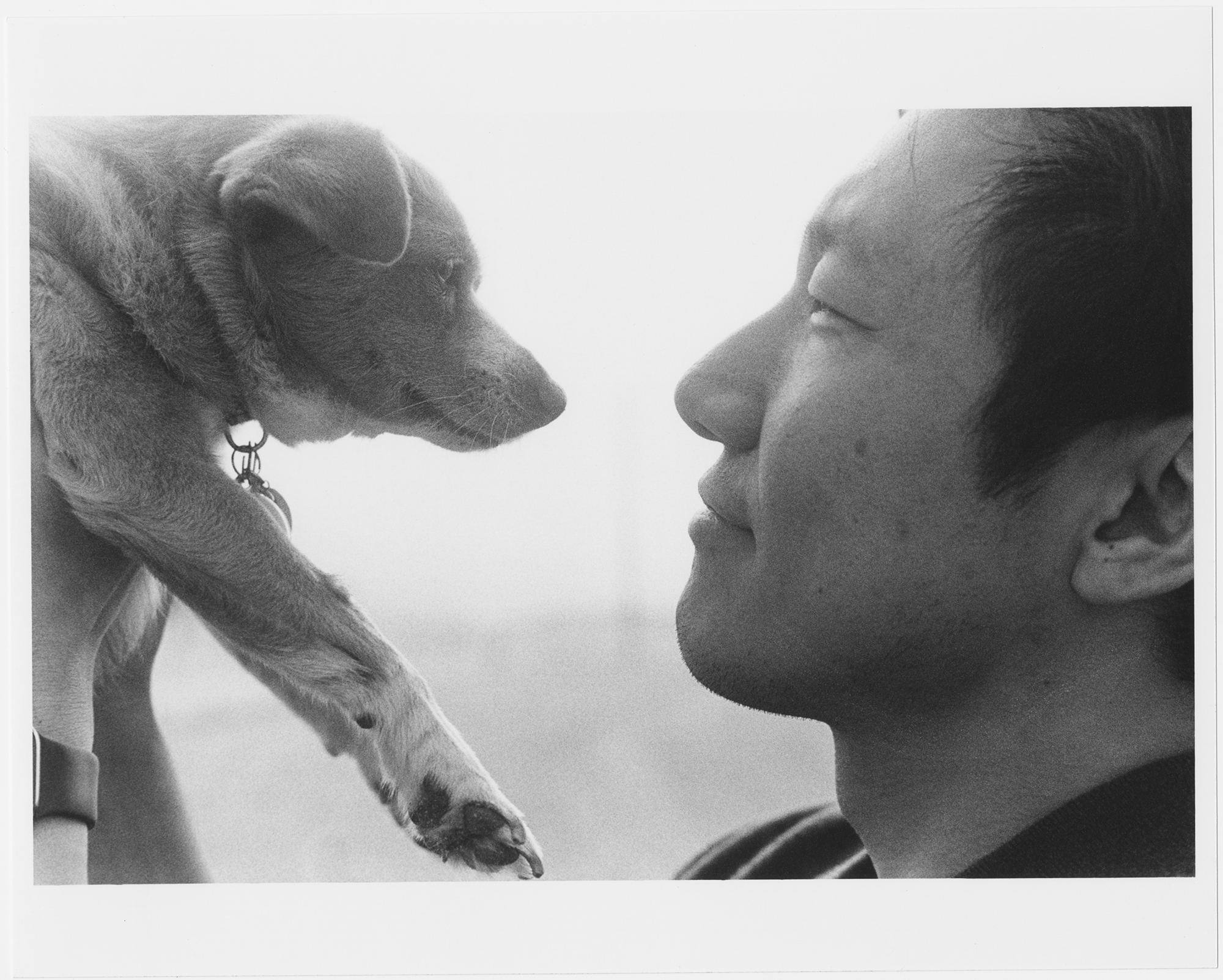

One of them was Hiro Murai, who graduated from USC’s film school, and by 2013 had cultivated his own idiosyncratic body of music-video work for artists like Earl Sweatshirt and The Shins. It was around that time that Murai met Donald Glover, sparking a collaboration that began with music videos for Glover’s alter ego Childish Gambino, and crescendoed with Atlanta, the highly influential FX series for which he’s directed the majority of episodes. Murai’s work can be terrifying (Atlanta’s “Teddy Perkins” episode), shocking (Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” video), and thrilling (his action set-pieces on Barry), but it is always provocative (all three). One person who’s been paying attention is Spike Jonze, who recently invited Murai to his Malibu home for a photoshoot, and to trade notes and observations from a life of making cool stuff.

___

SPIKE JONZE: Okay, we just lost the first 10 minutes of the interview, but to give a summary of what was lost, Hiro just got back from shooting season three and four of Atlanta. They did two seasons at the same time, because it’s hard to get everyone together, and the writers had enough material for two seasons. What else did we cover?

HIRO MURAI: I told you how I met Donald and then you thought it was way too boring of a story, so you basically wrote our backstory, which involved me having false teeth.

JONZE: Why don’t you say it like it’s true. How did you meet Donald Glover?

MURAI: I’ve had a history of dental issues since college. I don’t like talking about it. But apparently in college, I had pulled all of my teeth out, even though I’ve never done drugs.

JONZE: Except Advil.

MURAI: Except for Advil. But I apparently had a lapse in judgment, pulled all my teeth out, and ever since then my teeth have been fake.

JONZE: And you’ve had a lot of dental issues, which brings you to where we are, which is you on an airplane, going to South America, where they have some real good dental techniques down there.

MURAI: But I had taken too much Xanax on the plane.

JONZE: You were sweating profusely and happened to be sitting next to a guy who turned out to be Donald Glover. You didn’t know because you were so anxious. He gave you a full bar of Xanax and it knocked you out.

MURAI: For 14 hours. And then apparently I woke up in a car and Donald was driving me somewhere. I think. He abducted me essentially, but he was also taking care of me.

JONZE: But also, you had pissed your pants and you couldn’t wake up so he had to carry you off the plane.

MURAI: Yeah, I woke up with different pants that didn’t have pee on them and we fell into a Stockholm syndrome situation where I got folded into his artmaking and we’ve lived in the same house ever since.

JONZE: That pretty much brings us up to speed to where we lost the recording. So then I was just talking about when I first discovered your work. I saw three or four music videos, all by Hiro Murai. It was the Earl Sweatshirt “Chum” video, the Flying Lotus video, the Chet Faker video, and the Michael Kiwanuka video. Your ideas were all super complete and confident.

MURAI: Thank you, man. That means the world to me. The only reason I got into music videos is because in college I had yours, Michel Gondry’s and Chris Cunningham’s [Directors Label] DVD boxset. I didn’t even know that you could do that in music videos.

JONZE: Like do what?

MURAI: I don’t know, play? Because every video I’d seen up until that point was very glossy, artist-centric, selling the artist and selling the song, and it wasn’t an art in itself. I was in film school and getting really fed up with the pretense of it. I’m not a super ambitious person, so all these people were trying to make student Academy Award movies in film school.

JONZE: It’s so funny you say that, because when I first started making music videos, I felt everything was pretentious.

MURAI: It was the first time where I saw the director’s voice playing with the musician’s voice. Every time I saw you working with a new artist, I saw a slightly different side of you and how it bounced off the musician’s perspective.

JONZE: That’s cool. So you got out of college and then what did you do?

MURAI: I freelanced. I was doing a lot of camera operating for shows, and I draw a little bit, so I was doing storyboards for other people. And some VFX.

JONZE: That makes sense, because in all your stuff the photography and the visual effects is so integrated into the idea and used so appropriately, so it makes sense that you actually know how to do it. I just rewatched the “Black Man in a White World” video and I was thinking the effects are so confident and simple.

MURAI: I try to simplify the idea as much as possible, and make it feel intuitive and not overthought, even though a lot of times it is overthought.

JONZE: When do you feel like you’ve succeeded in that?

MURAI: The “Never Catch Me” video for Flying Lotus felt how I wanted it to feel. Part of the reason I ended up using a lot of dance in that is because I get to let go and just react to something that’s exciting me. You can’t get freer than people dancing, and so it felt like a good marriage of idea and concept. And then all I had to do was follow the lead of watching these kids dance their hearts out.

JONZE: Those long takes of the kids dancing, it feels so alive. Is that what you mean when something feels alive versus when something feels more constructed?

MURAI: A lot of times I don’t want to feel myself in it. I just want to be connecting the viewer to the thing they’re watching and try not to do so much, because sometimes that just feels like vanity or something.

JONZE: I totally agree. At a certain point I realized what I like to do is when you feel the characters have made the video or the film, as opposed to the filmmakers having made it. That’s the ideal feeling.

MURAI: When you made videos for various artists, what was the dynamic, usually? Because a lot of artists you work with are artists with very strong perspectives. How open are they to dipping into your world and how much are you dipping into theirs?

JONZE: For most of the artists I worked with, we had a shared sensibility. Whether it was Björk or Beastie Boys or Weezer, there’s always an overlap of the world we came from. And for every one of those, I wrote a treatment for an artist that was like, “No, I’m not going to be in a robot suit.”

MURAI: [Laughs]

JONZE: There’s a lot of artists that would say, “We want to work with that guy,” and then they’d see what I’d write, and they’d be like, “No.”

MURAI: The thing I remember very vividly from the Directors Label box set is the interview with Björk, explaining you pitching her the “It’s Oh So Quiet” video, where the mailbox turns into a man. She was like, “Spike got really excited and he was explaining how this guy is going to pop out and start dancing around.” And I was like, that’s so cool, that that’s a job where you’re taking someone else’s art and interpreting it as your own.

JONZE: What was your experience in finding artists that you worked well with or didn’t work well with?

MURAI: I did my fair share of pop videos in the 2000s. I was trying to squeeze myself into that space a little bit because especially at that time, the music video scene was so weird. And don’t get me wrong, I had fun doing it, but I did an Usher video and B.o.B video, and they’re both very traditional glossy pop videos. I was just trying to be like, “What would it feel like if I did these?” But it didn’t feel as fun to me.

JONZE: You were already starting to do smaller ones that felt more like you?

MURAI: The first thing I did where I felt, “I think I understand this,” was a St. Vincent video. The people involved felt they were all trying to make the same thing, which is the most important thing and also really rare. I did the first Earl video in 2012, and there was something about his world-weary, depressive, introverted rap music that was like, “I know what this is. I know exactly how this feels.”

JONZE: And which one was that?

MURAI: “Chum” was the first one. I actually just saw Earl yesterday, because he came to the Atlanta premiere. I hadn’t seen him for a couple years. He has a kid now, and he’s a whole grown human, but when we first met, he was 16, and he had just been thrust into this limelight and having an existential crisis.

JONZE: You could feel it on set?

MURAI: Yeah. It’s a lot. I couldn’t do anything like that when I was 16.

JONZE: What was your relationship with him at that point?

MURAI: The label put out a brief for a video and I pitched on it and he liked it. And then we met at Columbia and I had a giant picture of a frog in the treatment and Earl was distracted and half paying attention. And then he saw the frog and he’s like, “Hey, that’s me. That looks like me.” And it all clicked together.

JONZE: That’s rad. When you write, do you put the song on loop and listen to it over and over?

MURAI: Obsessively. I don’t know about you, but I can’t really listen to the song after I do a video for it.

JONZE: It takes me a little while for sure.

MURAI: I like to listen to it so much that I don’t even know it’s on. It usually takes 100, 200 times. But if I’m at a restaurant or something, and a song I did a video for comes on, I won’t even consciously know it, but I’ll start sweating and getting really anxious.

JONZE: Going back to Donald, how would you describe your collaboration and why it works?

MURAI: I’ve consciously not thought about it too much because I don’t want to ruin it. I’m realizing more and more that even with the crew and everything, it’s like alchemy. You try to put it in a bottle, and it ruins it. But I know that I enjoy working on things with them, we get excited, turn into kids and then we toss the ball around. And then by the time it’s done, it’s always something more than I thought it was going to be. I’ve just trusted that process in the 10 years I’ve known him.

JONZE: That feeling is so good. It’s where you give this thing and then they give it back but better, then you add to it. The sum of the parts is greater than the thing.

MURAI: Can I ask you something?

JONZE: Yeah.

MURAI: When you work with actors, and because you’re an actor in some capacity, how much do you know what you’re looking for when you’re working with an actor?

JONZE: I think I’m looking for a feeling and try not to get stuck on the way a line’s supposed to be. It’s more like I know what something’s supposed to feel like, and I know when I don’t like it and I know when and I like it. I try to do a take at the beginning where I don’t give them any direction. In rehearsal, we’ve talked about what the scene is about, but then on the day, I try not to say anything and just do the first take without any notes and then start pushing it and trying different things.

MURAI: Do you always rehearse before?

JONZE: Yeah, a lot. Sometimes because I just want to hear the thing read and see if anything needs to be rewritten, or sometimes because actors have such good questions. If there’s something in the script that’s cheated, like you need the character to do something to get the story to go somewhere, you’re always busted in rehearsal, and I’d rather be busted in rehearsal where I can fix it and also get their help fixing it. Some of it is to build rapport so we all trust each other and understand each other, so we’re not trying to get to know each other on the set. Do you like doing rehearsals?

MURAI: The way we fell into doing Atlanta, we rarely rehearse or it’s a very specific scene. Or we have a guest star and a lot of the weight is on their shoulders. The way we make the show is we just go in there and do what we can with the time allotted. We’ll try to play and do a lot of things that you’re talking about where if something feels false, we try to pick at why, and a lot of times we’ll just rewrite on the day. That’s the fun part about having Donald as a performer and writer. We can just poke at the things that aren’t working and flush it out. Other times we run out of time and the scene doesn’t work and then we rebuild it in the edit.

JONZE: From the first episode, Atlanta feels like this fully-formed idea, and it’s so specific and so specific to itself. Both the tone, the characters, the world and, but also the structure—it’s very free and lets itself go. It’s never preachy. It’s very humanist, and even though it touches on a lot of political things, it doesn’t feel like it’s being politically didactic, ever.

MURAI: We’re always caught up with that because it does touch on so many things, and we’re all contrarians, so we hate the idea that we’re all on a soapbox preaching to anybody. If anything, we want to be like, “What about this gray area? This is your stance on this issue or these people, but what if they were also complicated human beings?”

JONZE: That’s it. And it feels like it was that from the beginning.

MURAI: That’s great to hear.

JONZE: This must feel like a turning point, because it sounds like you guys probably aren’t going to do it again, is that right?

MURAI: Yeah. Season four has an ending, ending.

JONZE: You think you’ll never go back to it?

MURAI: Never say never, but we wouldn’t regret it if we never did it again.

JONZE: And how does that feel?

MURAI: Atlanta was the first narrative thing I ever did, so I learned everything on this show, and season four is very much a full-circle, back-to-where-we-started kind of season. And to be able to do that with this cast, who’ve all gone to become massive movie stars, to be back in that room just playing around, it just felt really good. It reminded us of how we started and where we’ve been since then. It was really moving.

JONZE: It’s an amazing cast. I don’t know if you ever saw The Outsiders, but it’s all these young actors that become movie stars and they’re all in one little place, and it feels a little bit like that. You guys have just had such incredible taste that you picked these people.

MURAI: I don’t think we can even take that credit. It could have been somebody else, but it would’ve been a completely different show. In some ways it feels like total blind luck because we didn’t know what we were doing when we made the first season.

JONZE: It’s blind luck-slash-intuition. For whatever reason you guys are looking at all these different people and you’re like, “This guy LaKeith’s interesting, or this woman Zazie is compelling.” You could have easily not picked them, but you were compelled by them. Do you think you’ll continue to collaborate with Donald on everything, or do you want to go off and do your own stuff?

MURAI: I’m doing something with Donald this year, but I’m also trying to develop features and different series. I’m following whatever is exciting to me at the moment and hope that the end result works. People ask me if I want to do a movie, but I keep thinking about seeing your short with the two robots [I’m Here] in college and thinking you can use any framework to tell a story. So I guess I’ve been trying to think about being medium agnostic. As long as there’s something sparking inside of it, it doesn’t matter what it is.

JONZE: I feel the same way. I look at my contemporaries that are film directors, and they have this huge body of work, and I’ve only directed four movies. I enjoy playing with different mediums. As you said, it’s the feeling you’re trying to get to. The medium in which you get there is secondary. Would you call yourself an artist?

MURAI: Yeah, I guess I would.

JONZE: Sick!

MURAI: [Laughs] Do you call yourself an artist?

JONZE: I would, yeah, but it took a long time because I was afraid it sounded pretentious.

MURAI: That’s hilarious. I’ve recently gotten comfortable saying that.

JONZE: I was so close with Maurice Sendak, and he really talks a lot about what it is to be an artist and live as an artist and the responsibility to yourself as an artist. It was through the course of our relationship that I probably got more comfortable thinking about myself that way.

MURAI: What’s his take on it?

JONZE: That you have to continually be honest. It’s hard to even sum up because he talks about it in so many different ways. When I started having ideas for Where the Wild Things Are, he asked me if I wanted to do it, and I was writing ideas and got really scared, because I realized how many other people had a relationship with the book and that I was making something so specific. I didn’t know if I should do the movie because a lot of people might be disappointed because they have something else in their head. And he just said, “As long as it’s personal and dangerous and doesn’t pander to children, then I support it entirely.” He wanted it to be personal to me the same way the book was personal to him. What was your relationship to thinking of yourself as an artist?

MURAI: I don’t know if it’s a Japanese thing, but presenting myself as something or wanting to be perceived as something always felt icky to me for some reason. It makes me feel very contrived, because at what point are you just performing that, versus just being that person? And so I hated the version of me that was like, “Hi, I’m an artist and please see me as such.”

JONZE: Right.

MURAI: But I fell in love with the process of making things more and more, and I think that love is very real, so once I accepted that, I was like, “Oh yeah, that’s what artists are.”

JONZE: Which is?

MURAI: Just the person who’s in love with making and expressing and playing with the world. Maybe that’s not what an artist is, but it’s the conclusion that I’ve come to.

JONZE: Yeah. That’s probably a good ending for the interview right there. “Hiro Murai, on being an artist.”

MURAI: [Laughs] I feel like I’ve come to a place of peace, and then I read this and it’s like, “I’m such an asshole.”

JONZE: But that’s what’s cool about being an artist. There is no clear definition for it. It has such an openness to it that it lets it be alive for everybody in a different way, and for some people like you, in a pretentious way…I’m kidding!!!

MURAI: [Laughs] Alright, I’m going to walk off into the ocean now.