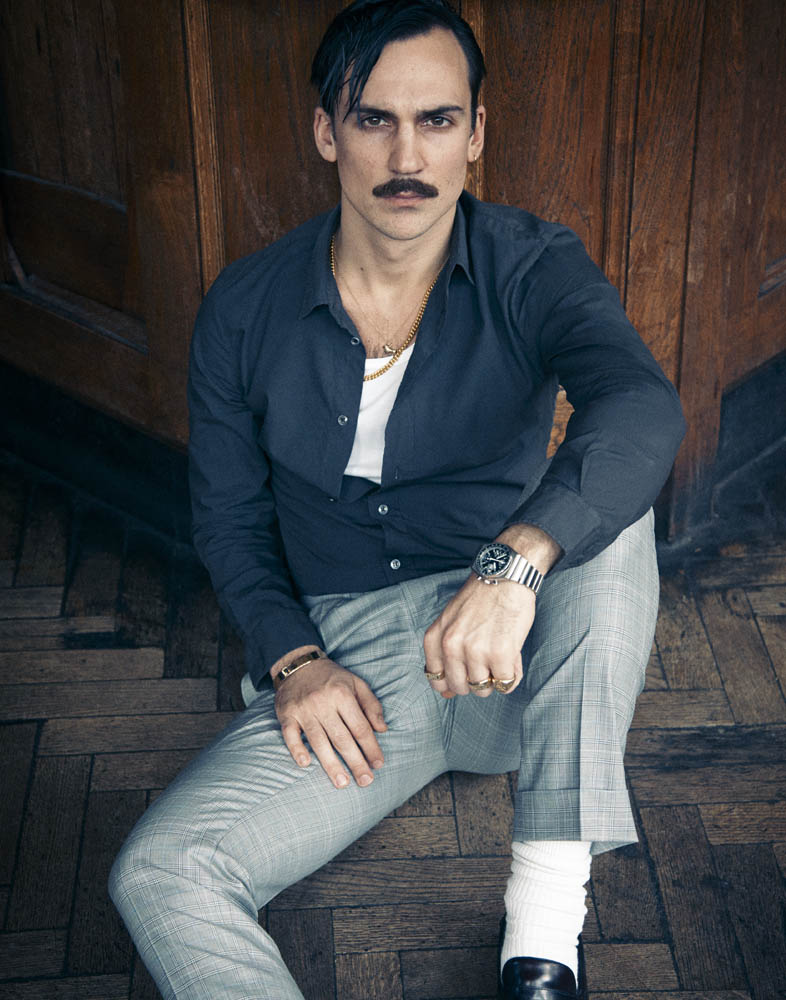

Henry Lloyd-Hughes

HENRY LLOYD-HUGHES IN LONDON, MARCH 2015. PHOTOS: MATT HOLYOAK. STYLING: OLIE ARNOLD. GROOMING: JOHN MULLAN/THE LONDON STYLE AGENCY. STYLING ASSISTANT: HOLLY FALCUS. SPECIAL THANKS: KAYTE ELLIS AGENCY.

In the eyes of Flaubert’s anti-heroine Emma Bovary, her husband Charles is stupid, suffocating, and physically repelling. He represents all that is wrong with the bourgeoisie and his devotion to Emma only exacerbates his flaws. For everyone else, however, it can go the other way: Charles is kind-hearted and sincere, Madame Bovary’s saving gracing.

“He wasn’t a bad guy,” says Henry Lloyd-Hughes, who plays Charles opposite Mia Wasikowska in Sophie Barthes’ film adaptation, out next week. It is not an easy role. “He needed to be likeable enough for you to stand him on screen, but there was something mind-numbingly small minded about him, something restrictive and conservative,” the British actor continues. “When you’re given characters who are really the end of the spectrum, quite extreme, it’s easy to pin characteristics to them. But the hardest things to do are always the characters that are just on the edge of things. You have to be so precise.” Lloyd-Hughes hopes the audience sympathizes with Charles, but only “enough to make the film heartfelt and hard to watch.”

Now 29, the London-raised Lloyd-Hughes has been acting professionally for over a decade. In England, he’s most famous for playing Mark Donovan in the cult comedy series The Inbetweeners, though he was also an original cast-member of Laura Wade’s play Posh, and has appeared in prestigious period projects like Parade’s End and Anna Karenina. Next up, he’ll make his big-budget American debut in Now You See Me: The Second Act and return for a second season of Indian Summers, the PBS series he helms set at the end of British colonial rule in India. Lloyd-Hughes’ younger brother Ben is also an actor.

EMMA BROWN: What was your first professional audition?

HENRY LLOYD-HUGHES: My first professional audition—god, I’ve never told anybody about this—was for a test commercial, I think it was for Xbox. It involved me getting kidnapped or something—bound and gagged—by a granny who wanted to play the Xbox. It was very weird and I definitely had no idea what I was doing. I actually got the gig. It wasn’t a commercial; it was what directors did when they wanted to show the company what they would do with a commercial. I remember they said, “Rolling,” “Sound,” “Speed,” and I just started doing the lines. I didn’t even know that you had to wait for them to say, “Action.” That was the first thing, and I literally haven’t thought about it until now.

BROWN: How old were you?

LLOYD-HUGHES: I must have been about 16. I was still in school. I did it in holidays. I was definitely in the spotty teenager realm.

BROWN: Did you tell anyone you were doing it?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Yeah! [But] it wasn’t like I boasted about it. I definitely didn’t think that this was 100 percent guaranteed paving the way to showbiz success. I think my mum told me about it, actually. I got a couple hundred quid or something and I was made. I was like, “This is amazing!” [laughs]

BROWN: What did you buy?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Probably clothes. I still spend most of my money on clothes. I probably bought some ill-advised teenaged purchases. I used to wear some pretty snazzy stuff. I was probably going through a fake fur coat phase—a mohair-type coat. It was pretty fierce.

BROWN: When did you decide that acting was something you were interested in?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Younger than that, when I was maybe in primary school. I remember doing—not Nativity plays—but school plays, and I remember thinking it felt good when people came up to me and said that I was good in a play. I wasn’t really used to that ’cause I wasn’t particularly prolific at sport, and I could get by at school, but I wasn’t going to win any prizes. Suddenly people were slapping me on the back and saying that I was funny and talented. So I just knew that it felt good to be appreciated, basically. Whenever I got an opportunity to do some acting I did a little bit more. Like the first job that I was just telling you about, it was just another opportunity to try something else. Once you get an agent you’re given an opportunity to try a little bit more. It’s a really long ladder.

BROWN: Have you ever had a moment of, “This is it, I’m here!”

LLOYD-HUGHES: No, definitely not. One hundred percent not. I thought you were going to ask, “Have you ever had a moment like, ‘This is it. I’m giving up.'” [laughs]

BROWN: Well, that too.

LLOYD-HUGHES: I think you have moments of doubt and moments where it feels really hard. You certainly have to be patient, and I’m a very impatient person. It’s been like when Yoda teaches Luke to be a Jedi; the things that I do professionally have taught me new levels of patience.

BROWN: What’s the best advice you’ve ever gotten about acting?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Probably from my dad, who’s not an actor, but he has a phrase, “Assumption is the mother of all fuckups.” [laughs] Which applies pretty much to everything.

BROWN: Your mother was an actor.

LLOYD-HUGHES: Absolutely. My mum was an actor until she started having children. I was the first child, so in a way I was the end of her acting career, which hopefully she’s forgiven me for. She had four kids, so it’s quite a lot of mummy-ing to do. My grandfather was an actor and my granny was an actor on my mum’s side as well. My great-grandmother, my grandfather’s mum, was a film hairdresser.

BROWN: She must have been encouraging if she was telling you about commercial test auditions.

LLOYD-HUGHES: Definitely. She’s still watches my show every week. It’s funny because I didn’t grow up in a household that felt like a theatrical household. My dad did a normal job and my mum had given up. But when I decided to do it—or try and do it—it wasn’t the most alien concept. There was still an element, certainly for my dad, of like, “This is lunacy.” But then once they could tell that I was serious, it was like, “Okay then.”

BROWN: You made films with your siblings when you were growing up, right?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Yeah, I made films with my brothers and my cousins and if any of the films ever come to fruition my career will be in ruins because the acting, writing, and directing is so unbelievably, heinously bad. We once screened one for my grandfather, this film that we had painstakingly made over a couple of days when we were all 10 years old, and he sat there and he said, “This is the worst film I’ve ever seen.” No sympathy whatsoever.

BROWN: Your brother said that your grandfather advised him to get a hat so he would be “Benedict, the man in the hat.” Did he ever give you advice like that?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Yeah. He told me that I should have a series of headshots, one with a tennis racket, one dressed as a naval officer, and one dressed as a cheeky chappie. He said, “If you have those headshots, the world is your oyster.”

BROWN: How did Madame Bovary come about? Were you approached or did you audition?

LLOYD-HUGHES: In one way it’s an amazing Hollywood story and in another way it’s kind of the real way that things work. I met Sophie, the director, in L.A. a couple of years before we actually ended up making the film, and I met her with this movie in mind. I read the script and we sat over coffee and it was just one of those “eureka” moments where it hit me instantly how I thought the film should be and what I thought the characters should be. I bombarded her, I lectured for about an hour and a half about, “This is the way that I think you should do the film and this is the way Charles should be and this is how their relationship should be and this is the kind of feelings that he should provoke,” and then she was like, “Yeah, that’s completely right. I really think you should be the guy in the film!” And I was like, “Wow, I didn’t realize that it was this easy!” Then, of course, there were months and years while they tried to put the financing together and it all gets really complicated and they’re lots of delays…it’s happening, then it’s not happening, then it’s happening, then it’s not happening. But eventually I was on set with another film and I just got an email from her. She said, “It’s happening, we’re going to film in a couple months.”

BROWN: Has a director ever told you, “that’s not what I’m going for” after you’ve expressed your opinions?

LLOYD-HUGHES: I can think of a handful of auditions where the director has literally said, “That is the opposite of what I think.” But it’s really good to be honest and have that dialogue. I don’t think you should be criticized though. I can think of one instance where the director was like, “What you said is the opposite, but I’m glad you told me that, that’s really interesting.” And then one instance where the director was like, “I don’t agree with what you said and you’re wrong.” I got annoyed. If you want an honest dialogue, you can’t criticize someone for what they say. You can’t teach someone to think in a certain way. I’m only here talking to you about this movie because Sophie fought for me to be in that film. So I’m incredibly grateful for her, I’ll always be incredibly grateful for her being generous enough to believe in what I thought. And it was just lucky that I met the right person.

BROWN: Has anyone ever hired you after saying that?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Nope!

BROWN: Does that make you nervous to voice your opinion?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Sure, but you’ve got to try. There’s something great about being a really young actor because you don’t have a chance to be nervous. You don’t know anything yet. Whereas one of the big challenges as you go through—I’ve been doing acting professionally for 10 years now—is to not let all the things that you know hold you back and make you more nervous. Once you’ve had a few people tell you that they don’t like your ideas, that voice in your head can creep in that says, “Don’t tell them what you think.”

BROWN: When you get a script and you’re not sure if it’s the right fit for you, is there anyone you talk to about it?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Yeah, my wife.

BROWN: Will she give her honest opinion?

LLOYD-HUGHES: Yeah, she has really good taste and it’s crucial to me to have a second opinion. I have a very strong instinct, but I’m sat here right now with a script—literally right now on my iPad—that I am in two minds about. Normally I’m like, this is more good than bad or more bad than good. It’s a rare occasion where I’m like, “Ehhh, I’m not sure what I think about it.”

BROWN: If you read a script that’s more bad than good but the people attached to it are really great, does that influence you?

LLOYD-HUGHES: No, I’m afraid not. I might have had a different career if that was the case. But if it’s not something where I can get excited about the making of the film, I just can’t bring myself to do it. I’m not cynical enough and canny enough to be like, “You know what, it’s going to make me unhappy but I’ll benefit in the long run.” I wish I was that guy, because it think it can be really helpful in your career to do that. But up to this date, I‘ve only done the things that I was happy to do.

BROWN: Does that upset your agent? “God, just take the role!”

LLOYD-HUGHES: Definitely. That’s another debate.

BROWN: Do you finish every script that you read?

LLOYD-HUGHES: You’ve got to finish it. I make a real point of it even if I am loathing every page. If you want to have the right to have that conversation with your agent—”I know you sent it to me, I know you like it, but I just really think it’s terrible”—you need to have the full details. You don’t want to be in that situation where your agent says, “What about after the first 20 pages where it turns into a psychedelic musical?” And you’re like “What? I thought it was an action-rom!” “In the first 20 pages it’s an action-rom, then it’s a psychedelic musical!”

MADAME BOVARY COMES OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE ON FRIDAY, JUNE 12.