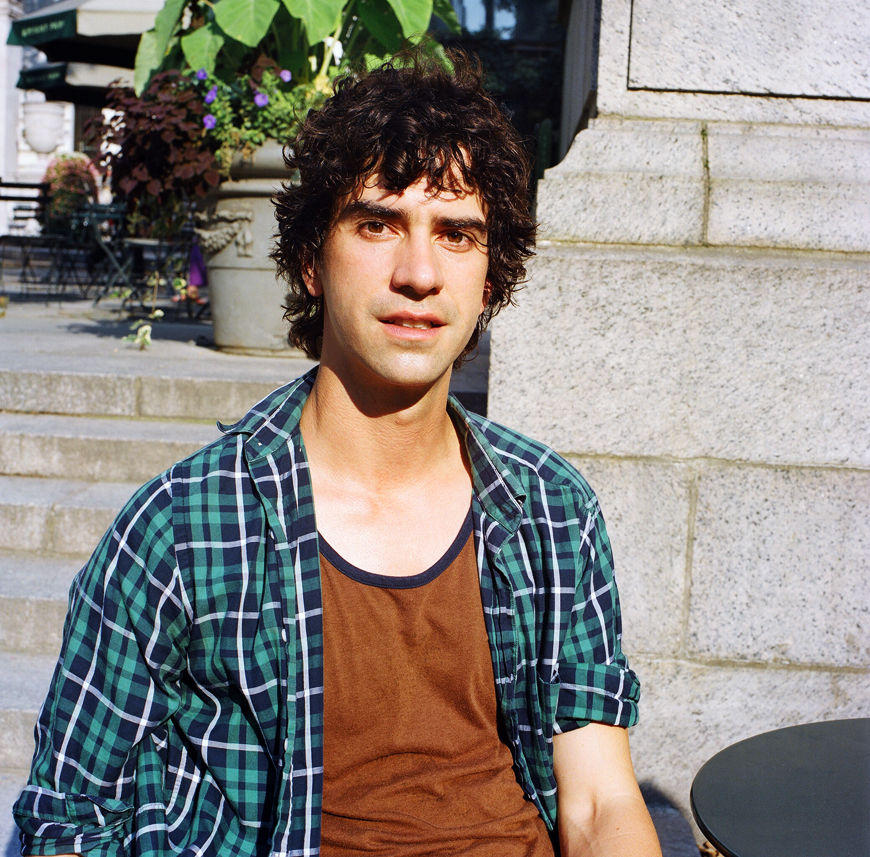

Hamish Linklater Stops Time, Fights Aliens, Discovers the Future

While most of us spent too much of our childhoods in front of the television, computer screen, or other time-wasting device, Hamish Linklater spent his childhood acting out Shakespeare. Linklater’s mother, Kristin, is the founder of Shakespeare & Company in Massachusetts, and he grew up with his very own theater in his backyard.

While Linklater is best known for his role as Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ deadpan brother Matthew on the sitcom The New Adventures with Old Christine, the actor has been steadily making name for himself on the stage. After stealing the show in both The Merchant of Venice and A Winter’s Tale last year, Linklater earned himself an Obie for his performance in The School for Lies this spring. Now Linklater is making the jump to leading man playing the sweet if unfocused Jason opposite Miranda July in her film The Future. The film is a gorgeous and heartbreaking look at two people in love trying to grow up. Next year, Linklater continues his ascent to the silver screen with a role in the blockbuster Battleship movie. We caught up with him to ask about growing up with Shakespeare in your backyard and how to improvise when aliens are attacking.

GILLIAN MOHNEY: Miranda July’s films have a very specific tone and style. Is she very exacting as a director when you’re working with her?

HAMISH LINKLATER: I think there’s a great deal of control in the process of creating a product that should feel light and effortless and so on. But the script is sort of perfect, and having seen the first film [Me and You and Everyone We Know, July’s debut] you can see how the scenes ought to be played and how the characters ought to sound. We rehearsed a good deal beforehand, because the production was going to be like lightning and there wasn’t much time to fuck around and find it. It was really intense, because you feel when you’re not in the world of Miranda July—when you’re in the wrong world. It’s very frustrating when a voice is so clear, and you’re trying to speak with that voice, and you can’t quite figure out how to do it. But she’s a great actress as well, so being in the scene with her is really easy. You kind of just have to get out of your own way.

MOHNEY: You’ve done a traditional sitcom and a lot of theater, and it was kind of surprise to see you in this movie where everything was so understated. Was that something that appealed to you?

LINKLATER: It was fantastic to be able to change pace like that and have Miranda have such faith in me that I could do that and find that. You want to have as much variety as possible, otherwise what’s the point? I went from that to Shakespeare in the Park and filling up a 2,000-seat house with blank verse. You want to throw yourself in as many uncomfortable places as possible, if you want to build muscles in uncomfortable parts of your body and grow as an artist, I guess.

MOHNEY: You grew up doing Shakespeare—does that impact how you approach work now?

LINKLATER: Yeah, I grew up at Shakespeare & Company. Actually, there’s this thing—one of the strictest verse people I ever worked with was Sir Peter Hall, and he has very strict ways of speaking a verse, where you have to breathe at the end of every line—and people really bridle at that and they want to play through to the period. The result is greater naturalism. You want to have handcuffs before you fly, or some crappy metaphor. But I think that’s what you get with Miranda. You get this product which is just flying, because you’ve gone down into the dungeon with her and put on the shackles and been beaten for a while.

MOHNEY: You’ve done so much stuff on stage; do you like being in the audience for your film and actually getting to see the complete work?

LINKLATER: I think I’m a pretty cliché actor in that I hate watching myself on film, but for this one it’s a weird experience because I’m so proud to be in it. I don’t know why it should be humbling to see yourself on film. But it’s bizarre. It’s different each time I see it. The first time I saw it, it was in a basement with my family and no one could move. It was very tense. Then the next time it was at Sundance in a big huge theater. It was a relief. I was glad I had seen it once and could sit back and relax with all those people, and you feel the emotions of the house. It’s not yours; you can just feel grateful at that point, if the movie’s good. I felt grateful, ultimately.

MOHNEY: Was it your first time at Sundance?

LINKLATER: I had been there 11 years previous, with the first movie I had ever done, and the first time I had acted in front of a camera. It was this movie called Groove; it was like a rave movie. And it became very popular during the week of Sundance and then afterwards not so much. It was so intense and overwhelming—

MOHNEY: How old were you?

LINKLATER: I was 23. I was like “Oh, I’m going to be at Sundance every year!” Then a decade passes. But that was so overwhelming; I went to all the parties. I was mainly sitting on Main Street sobbing and wondering where my girlfriend was. All my agents thinking I was leaving them. So I thought, “Oh, now I’m a fully-grown human being going back, and I’m not going to cry.” But I cried all the same! It was like old-man tears or mid-career tears. The movie was so moving, and I was really so grateful to be back.

MOHNEY: I wanted to ask you about growing up with Shakespeare & Company. Did you know when you were little this is what you wanted to do?

LINKLATER: It was my home, and there were all these actors in it, and they were always doing plays. That’s what home was. I did try to go to college and try to be an English major.

MOHNEY: Did you ever want to rebel and just be a lawyer or something?

LINKLATER: I didn’t have that much ambition. I liked school a lot, but it was really—it really wasn’t home. I went to Amherst College and dropped out at 19 and moved to New York City to become an actor. I love that Shakespeare in the Park is so beautiful, because it was an outdoor Shakespeare theater that I grew up at. That feels like home, and the place I’m always trying to figure out how to get to. … They started putting me into plays when I was eight or nine. Or making up characters for me, like in Antony and Cleopatra, have an eight year old who wears tighty-whities under his toga. I think it was mainly to cut down on babysitting costs. If I’m onstage, mom knew where I was.

MOHNEY: You loved it as a kid?

LINKLATER: Yeah, we lived in the house that was the backdrop for the stage. You’d walk downstairs, put on your costume and walk on stage. The stage was just part of the world.

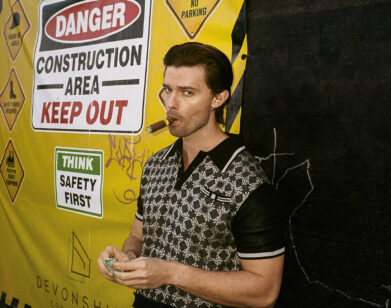

MOHNEY: You did this tiny movie and then a play where you won the Obie—but how was it to go from those smaller productions to working on blockbuster like Battleship? Were you prepared for all the green screens?

LINKLATER: Most of my stuff wasn’t with green screen. I think a lot of stuff on the boat was green-screen stuff. My stuff was all running around in Hawaii.

MOHNEY: So that’s not too bad.

LINKLATER: It’s not bad. But it’s weird, though, because you’re in this hotel with all these tourists and you’re kind of working and trying to focus. Working in a vacation destination is kind of the stupidest. It’s like reading a book on a rollercoaster. It was me and Brooklyn Decker and this guy Colonel Greg Gadson, who is active military and lost his legs in Afghanistan.

MOHNEY: Oh wow.

LINKLATER: It was the three of us running around trying to figure out why the aliens are there and explaining all this. It was the opposite of Miranda, and the opposite of Shakespeare in the Park. Peter Berg is the director and just the unbelievable best. He was like, “This script—eh, we’re just going to improvise!” But all of my stuff was “geo-synchronism orbit” and all this science jargon. There was no way I could just make it up. It was really fun, but that was the scariest thing in the world. If I have iambic pentameter I have something to hold on to. But if they say, “Just improvise!,” it’s terrifying. But he also does it with like four cameras running all the time and he’s yelling directions at you. It’s completely discombobulating and distracting, which is probably what it’s like when aliens attack for real.

THE FUTURE OPENS IN LIMITED RELEASE JULY 29. BATTLESHIP OPENS IN 2012.

PHOTOS, ABOVE, BY AARON STERN