Grey Gardens

Â

In 1973, when filmmakers Albert and David Maysles, along with Ellen Hovde and Muffie Meyer, directed a 94-minute documentary about a reclusive mother and daughter who bore a passing relation to former first lady Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassisâ??and their madly eccentric lifestyle inside a crumbling, cat-ridden East Hampton mansionâ??they could never have suspected the impact that Big and Little Edie Bouvier Beale would have on American culture. Due to Grey Gardens, the Beales became instant and permanent cult figuresâ??as much for their painful fall from privilege as for the tremendously antic personalities that found them feeding raccoons in the attic, dining on cat food, and dancing an American flag salute in the downstairs foyer. Little Edie transcends cult stardom. Her highly individualistic dressing style (she was known to turn almost any piece of fabric into a turban) transformed her into an enduring fashion icon. Even in recent years, designers such as Marc Jacobs and John Galliano have created collections that evoke her spirit.

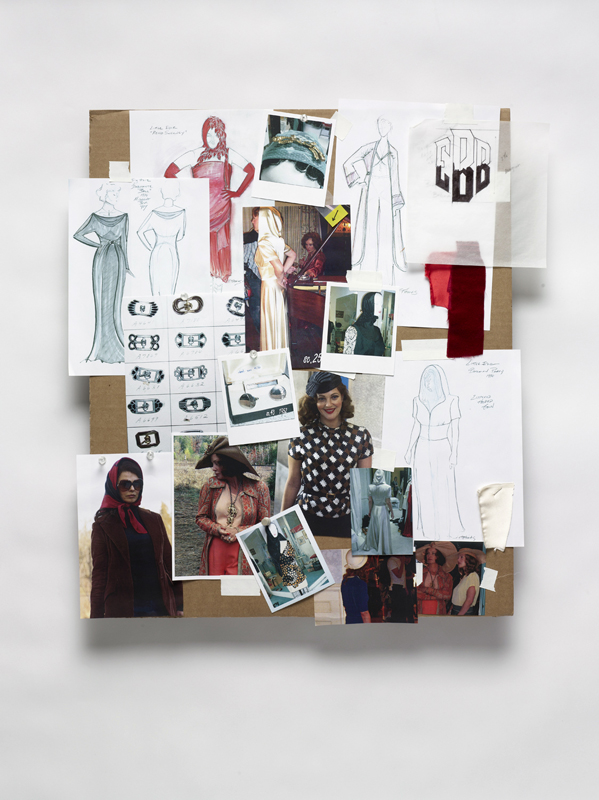

When first-time director Michael Sucsy set out to make a feature-film version of Grey Gardens, he was armed with two top-tier actresses to play the leads: Jessica Lange as Big Edie and Drew Barrymore as Little Edie. But he also had to worry about staying true to the mother and daughter’s predilection for outrageous ensembles lest he sartorially offend legions of Grey Gardens fans. Costume designer Catherine Thomas was hired to dress Big and Little Edie in looks meant to reflect their lives over the course of four decadesâ??from their heyday as proper New York debutantes to their reclusive piecemeal lives of squalor. Actress, fashion designer, and hardcore Grey Gardens enthusiast Tara Subkoff talked with Thomas about refashioning the Beales for our time.

TARA SUBKOFF:â??Hello?

CATHERINE THOMAS: Can you hear me? I’m trying to find a place that doesn’t sound crackly.

TS:â??You sound like you’re shopping somewhere. Are you shopping somewhere?

CT:â??I’m not. I’m at Drew [Barrymore]’s house up in the Hollywood Hills.

TS:â??Please send her my love. She’s phenomenal in the film. At first I was wary, because I’m such a fan of the documentary. But it completely blew me away.

CT:â??Yes, she blew me away, too. There were so many risks on all sides in the production.

TS:â??It must have been very tricky to do the costumes for the feature version when the original documentary has been such a constant source of fashion inspiration. How did you decide to take on this project?

CT:â??I have loved Grey Gardens for so long. When I heard about the project, I begged my agent, “Please, just get me an interview. If you can get me that I swear I’ll get the job.”

TS:â??What did you think when you first watched the Maysles’s documentary?

CT:â??Truthfully, I thought they were these two crazy women. It’s not until you start getting into the layers of who these women were that you start realizing what made them that way.

TS:â??And what did you first think of their clothes?

CT: In some ways it was very childish. It was literally like dressing up for the camera. You have to think, when they weren’t around the Maysles brothers they were probably acting a little differently. So there is some degree of fantasy to the wardrobe. But what’s interesting is how they flip-flop in their roles of mother and daughter . . . in the way they act and in their clothes.

TS:â??There are moments in the feature that help to explain some of the mysteries that left me curious in the doc. Such as the scene where Little Edie’s hair is falling out and she is so ashamed and panicked about it. It really made me feel for her and understand her and the turbans in a way I hadn’t before.

CT:â??Yes, the turbans! Really, she handles her hair loss in such a progressive, positive way. She makes it her own. It was so essential to reach beyond the years of the documentary. We start in the 1930sâ??even the white satin hooded gown that Little Edie wears to the bohemian party is a beautiful metaphor for what’s going to happen later to her, covering up her head. Obviously, we compiled a lot of research. Surprisingly there were more photos of Little Edie than of Big Edie. For the 1930s, Big Edie was really what we imagined her to be like.

TS:â??The 1930s are my favoriteâ??all that glamour!

CT:â??The way things were cut in that decade was a real turning point for women’s fashion.

TS:â??Did a lot come from thrift stores?

CT:â??It was a combination. For the early years, we basically constructed everything from scratch. The later years was an amazing process because it was like scavenging. Even if a piece wasn’t an exact replica of what we saw in the documentary, if it felt right to that world then we’d use it. Another important thing we did was repeat clothes that they had throughout their lives. We had a sort of shared closet, because Big and Little Edie would swap clothes, so it turned into a decoupage of all of the periods.

TS:â??I noticed you were very deliberate about your color palettes to signal the different decades.

CT:â??Yes! I’m sure you remember those black-and-white graphic pants from the ’50s. We also had a teal color that repeats for Little Edie from the early ’50s on. And by the 1970s, the time of the Maysles’s footage, the colors and patterns were really out there.

TS:â??So things really fell apart for them in the 1960s?

CT:â??I would say in the ’50s, when Little Edie is forced to go back to Grey Gardens to live.

TS:â??There’s a scene between Little Edie and Daniel Baldwin, who plays Julius Krug, her only true love, that is absolutely heartbreaking. Everything fell apart for both of them when their hearts were broken-which makes sense to me because I’ve been broken-hearted . . . I’m sure you have, too. It’s almost like you decide to withdraw from life and stop caring and give up. It felt like both women just gave up at the same time, and so much of their psychology is revealed in the film by what they choose to put on. I think that’s true in real life too. You can tell whether you’re happy or not by what you put on your body.

CT:â??It’s interesting that you brought up the scene with Daniel Baldwin, because Little Edie was wearing those black graphic-print capri pants. It was a struggle to get Drew to let her guard down enough to be vulnerable and it was a very specific choice to have her look so out of place in that hotel, compared to everyone else. Every actress has insecurities and sometimes you have to play off of them to get the appropriate effect. Of course, Drew hated me when we shot that! It would have been too easy to make her look fabulous . . .

TS:â??In my mind that’s the point that changed Little Edie. And then her hair starts falling out . . . How did you construct the turbans?

CT:â??It involved playing with fabric and seeing how it draped. I truly think that’s what Edie did, you know? She would wear something as a sweater vest and then the next day she would put it on her head. I have to tell you, the woman was a genius. After playing with those head wraps and realizing how many safety pins we needed to make them stay, it’s incredible how she managed it. That’s why, in the documentary, you always see her adjusting her turban.

TS:â??I liked the scene where Jackie Kennedy visits. She drops her scarf before she leaves and Edie adopts it into her wardrobe.

CT:â??We took liberties. Who knows if Jackie ever dropped that scarf? Probably not. But we thought the scarf was a great vehicle because there is an animosity between Jackie and Edie.

TS:â??You don’t see Little Edie actually pocketing it.

CT:â??You never see that. I’m really amazed you noticed. It was a little inside secret we put in the movie.

TS:â??How involved were Drew and Jessica with the costumes? Did they have a lot of opinions?

CT:â??I think there are never too many opinions in a collaboration. Drew really trusted me and Michael to guide her. But I realized while I was working with her, “God, Drew loves clothes. She loves fashion . . .” But she really let us give her the proper ammunition to get into the character of Little Edie.

TS:â??We haven’t talked about Big Edie, Jessica Lange’s, costumes. Did you evolve Little Edie’s costumes out of Big Edie’s?

CT:â??I sort of did them simultaneously. Big Edie in real life was actually much heavier than Jessica. In the documentary she had lost a ton of weight. But we really wanted her to have a breezy feeling, that she was living in this very casual environment and that she had friends who were artists and she was truly this bohemian woman. So we used lighter fabrics.

TS:â??Did you want to build slowly to that point where they’re crazy and cooped up together?

CT:â??It was a slow build. I think Jessica’s character in the ’50s was still kind of keeping it together. The turning point is really after the funeral of Little Edie’s father [who died in 1956]. By the ’60s they are sitting in bed together listening to radio broadcasts. They’re older, and the holes start to appear . . . The two of them really just began to live in their own worlds. They fed off of each other negatively and positively. They were each other’s best friends and each other’s worst enemies at the same time.

TS:â??The film turned out so beautiful and whimsical. You really captured the magic.

CT:â??There was a lot of fear and insecurity, especially dealing with two characters who are so iconic. We’d all get to the point where we’d ask, “Oh, my God, are we fucking up?” But we trusted our instincts.

TS:â??And didn’t worry about the end result . . .

CT:â??If you do then you’re totally screwed. We didn’t want to recreate the documentary. We needed to find our own place with Big Edie and Little Edie. That’s what makes it compelling.