Gregg Araki’s Woman on the Verge

White Bird in a Blizzard begins with a song by the Cocteau Twins and Harold Budd: “Sea, Swallow Me.” You’re in 17-year-old Kat’s world now, and though things should be simple—a suburban teenager coming home from school in 1988—everything is coated in haze. Most of this is because of Kat’s mother, a dissatisfied housewife dressed like Tippi Hedren who oscillates between a barely-there daze and a seething hatred for her ball-and-chain husband and daughter. But even Kat’s father, with his thinning hair, moustache, and white-bread button-down, seems too dulled to be real.

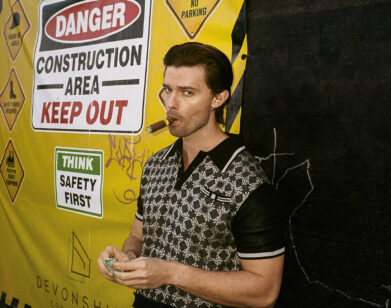

Director Gregg Araki’s ninth film to screen at the Sundance Film Festival, White Bird in a Blizzard, is adapted from the novel of the same name by Laura Kasischke. Shailene Woodley (pre-Divergent) plays Kat, with Eva Green as her mother Eve, Christopher Meloni as her father, Gabourey Sidibe and Mark Indelicato as her best friends, and Shiloh Fernandez as her none-too-bright boyfriend, fond of almost-there idioms like “absence makes the heart grow stronger” and “cut me some slacks.” In a voiceover, Kat tells the audience that her mother has disappeared. She spends the rest of the film hovering towards an explanation.

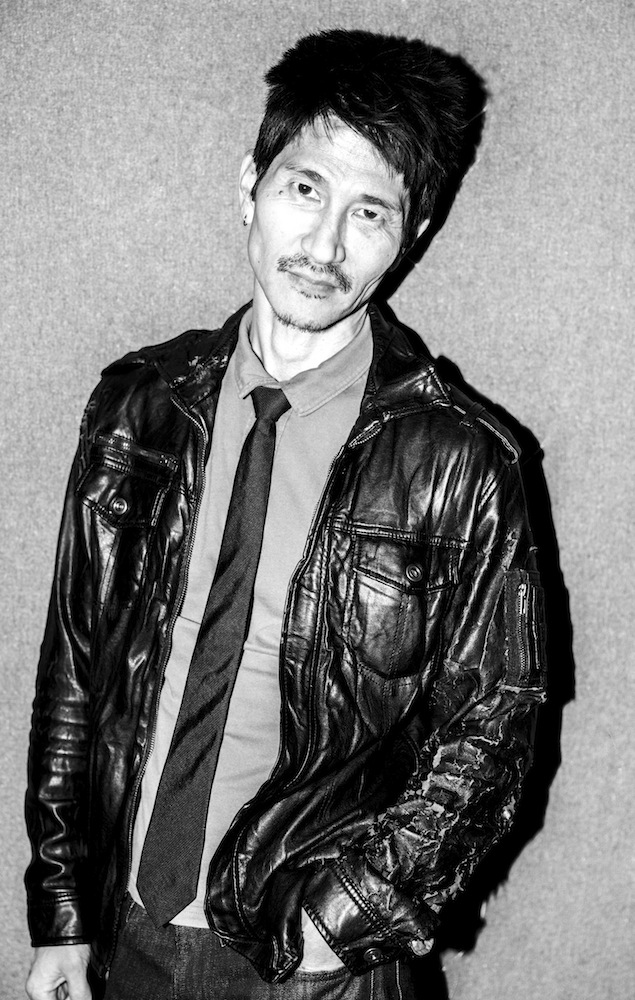

Araki is well-known for his lyrical films with mesmerizing soundtracks, with 2004’s Mysterious Skin, about a teenager trying to piece together five blacked-out hours from his childhood, as his most lauded. We spoke with the 54-year-old Southern California-native last week in New York.

EMMA BROWN: You’ve mentioned in the past that you discussed Beetlejuice and Heathers-era Winona Ryder as a reference for Shailene’s character Kat. What were some of the references for Eva Green’s character Eve?

GREGG ARAKI: Eva and I had a different conversation. It was very important to me that her character not be one-dimensional, like the evil stepmom. I really saw her as this tragic figure. My idea of her—and this comes from the book because Laura’s background is in feminism—was that the character was born in 1946, and she was raised on that image of Jackie O. and Elizabeth Taylor and the Hitchcock women—these icons of the perfect woman. They always look perfect; their hair’s perfect, their make-up’s perfect. They’re wearing the perfect outfit. There are flashbacks in the movie to the ’70s when she was first married or when Kat is a young girl, and she was living this life that was prescribed for her by society. That’s why I find her character so sad. Eve has her breakdown, she realizes, “This isn’t my life. Who am I? What am I doing?” I thought Eva did such an amazing job of capturing that sadness. I worship Eva Green; I think she’s amazing.

BROWN: Eve is a product of her time. In your opinion how many years, or decades would need to pass before a woman like Eve could escape such a trap?

ARAKI: The story between the mother and daughter is interesting in that way, because it’s a generational thing. Women had more choices in the ’80s than they had in previous years, but at the same time, I do feel like [Eve] is on that cusp. The Eve character grew up in the ’50s and the ’60s, so feminism was beginning to take hold and grow, but those images that you see when you’re young—when Eve was, say, 16-years-old—that’s a really powerful thing when you’re figuring out who you are and what you’re going to become. For Kat, she’s next generation. In the movie, she leaves her life behind and goes away to school and is introduced to this whole other world. The Eve character never had that chance.

BROWN: Do you think Kat realizes that about her mother?

ARAKI: When she’s in therapy, Kat has those realizations about, “I guess my mom had no other choice.” They had this weird love-hate relationship that I think is very common for women. The sort of understanding she has of her mother and her unhappiness and where it’s coming from, I find very touching.

BROWN: Do you think an equivalent father-son relationship archetype exists?

ARAKI: I think there are similarities, but there are real differences too. That was one of the things about the book that really struck me, its feminist point of view. Most coming-of-age stories are told from a male point-of-view; even if there’s a female protagonist, it’s almost like a male version of what the girl is going through, versus this movie, which is so steeped in that point-of-view. The way Kat views sexuality and her own identity, it’s all very organic and very true. I think it’s coming from Laura, and that’s what really drew me to it.

BROWN: What were the iconic images when you were growing up? Your equivalent of a Jackie Kennedy.

ARAKI: I saw the same images as the character, but it’s almost the same question related to African-American people: because you’re not a women, you don’t see those images in the same way. It’s the same way for African-American people; it’s very different, because your perspective is completely different—it’s almost related to racism in that way. The way this patriarchal system was set up is that most of these images are propagated and created by men. As a gay person, I think that I see it from a more minority point of view, but it is what society prescribes as “this is the way things are and how they should be.”

BROWN: When did you come across the book?

ARAKI: The book was brought to me by my French producers. They had actually optioned it and sent it to me and asked me if I would be interested. We were looking for a movie to do together. I read the book and I was bowled over by it. I found it to be so beautiful and the story of it so haunting. It’s written in this very beautiful poetic language. It begged to be a movie. It has a very cinematic quality—the dream sequences and the snow and the imagery of the movie, I could really see it very vividly in my head as I was writing it. That, for me, is the first step to a movie that I could do or would be interested in doing—seeing it in my head and really getting a feeling for it.

BROWN: Do you follow how your films are received? When you’re at Sundance, do you look to see if the response is mainly positive or negative?

ARAKI: Like Rotten Tomatoes? [laughs] I don’t a lot. At certain times I do. I read certain reviewers. I don’t Google myself. I’ve been doing this for such a long time, and I know that every movie is different. I try to make movies that I love and that I’m passionate about and that I’m proud of. I always find that there’s no way to guess. I remember Gus Van Sant told me that once: You just make the best movie you can and hope for the best, because you don’t have any control over what happens with the movie, whether the movie is misinterpreted. The example I always use is Mysterious Skin. When I made it, my movies had tended to be very controversial. People loved them, they hated them. They were very polarizing in that way. It was something I was very used to. I remember specifically when I started Mysterious Skin going, “This movie is so sensitive, what it’s about. I love it and I really want to make it, but it’s one of those movies that the people who hate it are really going to hate it, and it’s going to be the end of my career. People will be so upset about it that there will be a witch-hunt and I’ll be driven out.” And then Mysterious Skin turns out to be the one movie of mine that everybody loves. Even the people who don’t like my movies love Mysterious Skin. So at this point, I just don’t even second-guess any of that.

BROWN: I know everyone asks about the music in your films, but White Bird in a Blizzard has a wonderful soundtrack. Did you start with any song in particular?

ARAKI: I picked the music in this movie super carefully. A lot of it is actually in the script. I wanted to pay tribute to these groups and this music that were so influential to me when I was coming of age as a filmmaker. It’s not really, to me, just songs in the background; it’s very much part of the heart and soul of the movie. After Shailene and the younger people—Gabby and Shiloh and Mark—were cast, I gave them all music CDs of the music that the characters would listen to. It was such an important part of who they were and what their characters were about and where they fit in society. I’m so amazed that we were able to clear all the music I put in the movie because it’s the Cure and New Order and Depeche Mode—all those huge important alternative bands of that era.

BROWN: Did any of the bands ask to see the movie before allowing you to use their music?

ARAKI: In the past I’ve had like Nine Inch Nails or whatever [ask], and we have to set up a special screening. But we were actually just able to clear it. For instance, This Mortal Coil at first didn’t clear, and then I wrote a letter to Ivo [Watts-Russell] and begged him for it and he was familiar with some of my movies and said, “Okay, for you!” [laughs] I was very fortunate in that way. We were able to get basically everything that we wanted.

WHITE BIRD IN A BLIZZARD IS OUT IN SELECT THEATERS TODAY, OCTOBER 24, AND AVAILABLE VIA VOD.